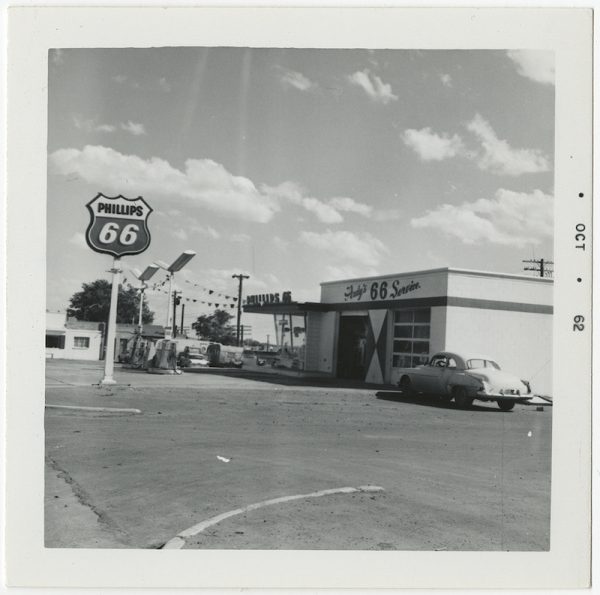

Ed Ruscha, Phillips 66, Grants, New Mexico, unpublished outtake from Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1962. Gelatin silver print, 8.8 x 8.9 cm. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

I can’t remember when I first became aware of a small book by Ed Ruscha entitled Twentysix Gasoline Stations, published in 1963. Like other artworld landmarks of my youth, the volume seemed as much an established fact as the Mona Lisa. But I do recall a vague and curious sense of comfort — actually, an irrational degree of happiness — knowing that such a book existed.

Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin excavates the nuts and bolts of the artist’s singular bookmaking. The exhibition peeps into his notebooks, unveiling moments in his process of “viewing” and “responding” to the landscape of the modern American West. And in the cavernous Ransom gallery, you can savor the intimate, tactile experience of actually picking up, holding in your hands, and leafing through seven Ruscha books: Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Various Small Fires and Milk, Some Los Angeles Apartments, Thirtyfour Parking Lots, Real Estate Opportunities, A Few Palm Trees, and Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass. An unfolded copy of the accordion-fold book Every Building on the Sunset Strip is exhibited in a long, narrow stand under Plexiglass.

The exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance” at the Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Derek Rankins. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

Featuring some 150 artworks and artifacts, the exhibition also includes Ruscha paintings, drawings, and photographs that were produced as material for the books or were later instigated by and/or retooled from book project contents.

At a packed-house talk with curator Jessica S. McDonald on September 6, the artist confided that much of his work has explored variations on themes that have shaped his worldview and aesthetics since the age of 18. “Everything was formed in me at that age.” The following year, 1956, Ruscha headed west from his native Oklahoma, traveling the storied passage of Route 66, to attend Chouinard Art Institute (which became CalArts) in Los Angeles. Remaining in L.A. after school, he trekked back and forth a half-dozen times per year, acquiring a distinct notion of the importance of these oases de petro — gasoline stations — for the contemporary highwayman. “They are like trees because they are there,” he explained in a 1985 interview. “They were not chosen because they are Pop-like but because they have angles, colors, and shapes, like trees.” According to one source, Ruscha placed copies from the first edition of Twentysix Gasoline Stations for sale at the actual stations along his route.

During the September 6 talk, McDonald power-pointed a letter the artist received from the Library of Congress in 1963, in which a librarian explained that the august palace of printed matter was returning the gifted copy of Twentysix Gasoline Stations, not wishing to preserve the inscrutable tome amongst its collections. Ruscha highlighted the rejection in an Artforum ad, which is included in the exhibition; the magazine’s 1963 editor found the book “so curious, and so doomed to oblivion, that there is an obligation, of sorts, to document its existence.”

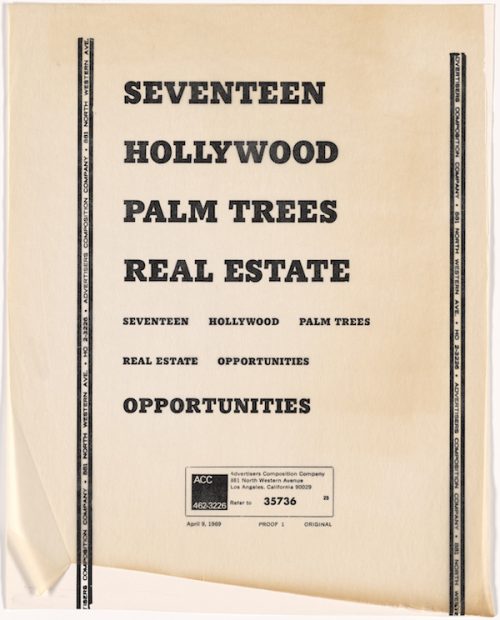

Advertisers Composition Company, Los Angeles, Reproduction proof, type set for Seventeen Hollywood Palm Trees (working title) and Real Estate Oportunities, by Ed Ruscha, April 9, 1969. Offset on paper, 26.0 x 20.2 cm. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

After his second book, Various Small Fires and Milk, appeared in 1965, Artforum ran a two-page spread (on view at the Ransom), in which “Ed Ruscha Discusses His Perplexing Publications.” The 28-year-old artist explained that the photographs in his books were not “’arty’ in any sense of the word” and that he regarded them as “technical data like industrial photography.” As for the layout of the books, Ruscha stipulated that “the pictures have to be in the correct sequence, one without a mood taking over.” As good an explanation as any, he described an edition of a Ruscha book as resembling a collection of “readymades” and referenced “the thrill of seeing 400 exactly identical books stacked in front of you.”

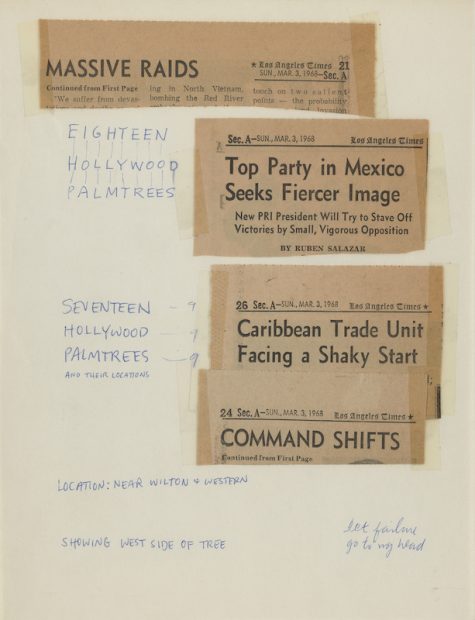

Ed Ruscha, Preliminary notes, A Few Palm Trees, 1968. Ink on paper with news clippings, 26.6 x 20.3 cm. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Archaeological relics on display, unearthed from the Ransom’s Ed Ruscha Papers and Art Collection, acquired in 2013, include printers’ invoices for the books, sewn and uncut book pages, dummy mock-up copies, typesetting and printer’s proofs, film exposure notes with names and locations of gasoline stations, camera-ready paste-ups, and studies and sketches. All together, the publication innards feed typographic fetishes and trigger bibliographic nerd alerts. I suspect I will visit this exhibition several more times.

Also during the artist talk, McDonald and Ruscha discussed Ruscha’s youthful enjoyment of a publishing format called Big Little Books, popular from the 1930s to the 1950s. Approximately 3.5 inches by 4.5 inches and 1.5 inches thick, the volumes resembled, as Ruscha described them, brick-like pieces of sculpture. (I have lingered enrapt over Big Little Westerns with their colorful graphic covers at Book and Paper Shows.) Included in Archaeology and Romance, the small, green, chunky catalogue, Edward Ruscha (Ed-Werd Rew-Shay) Young Artist, for Ruscha’s first major museum exhibition, held at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in 1972, recalls those volumes. To achieve the effect, Ruscha’s big little catalogue features 175 added blank pages.

“Enact ambiguous scenarios.” Amongst a collection of Ruscha’s books installed under glass with their contents out of view, the 1978 book Hard Light, a collaboration with artist Lawrence Weiner, reportedly presents images that, much like film stills, “form a narrative sequence in which three women enact ambiguous scenarios around Los Angeles.” The enacting or representing of “ambiguous scenarios” could serve as a category descriptor for the aspects of Ruscha’s Ransom Center iteration that embody or suggest some form of “romance”.

The exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance” at the Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Derek Rankins. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

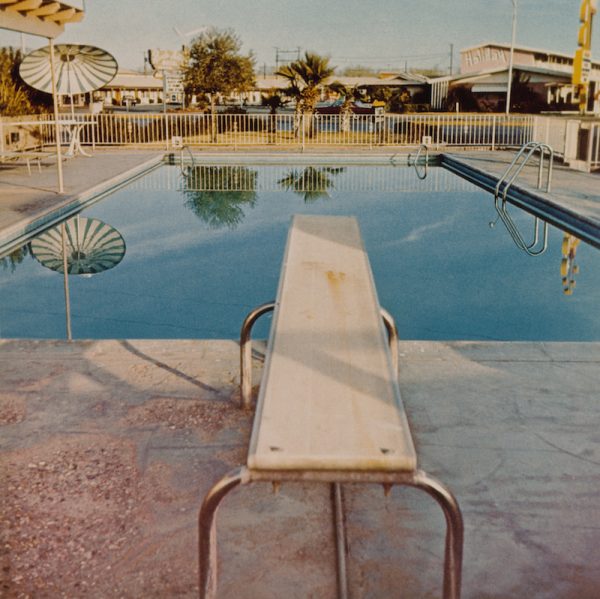

Ed Ruscha, Pool #2, from the portfolio Pools, 1968; printed 1997. Chromogenic color print, 40.4 x 40.7 cm (image). Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

The patches of postmodern frontier sod in Real Estate Opportunities and the spin-off portfolio of gelatin silver prints, Vacant Lots, strike me — especially after a recent immersion in the images of William Henry Jackson, Timothy O’Sullivan, and other 19th/early 20th-century photographers of the Western landscape — as tiny, rebellious refuges of a still-wild West struggling to break from civilization’s subjugation. And the sandy-beige surroundings of the aqua-turquoise bodies of water in the chromogenic color prints entitled Pools create an effect of spring-fed desert oases. (Wall text informs that Ruscha instructed the printer of the images in Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass to withhold the black layer of ink from the four-color printing process of the book’s images, “giving the images a bright, sun-bleached feel with little depth in the shadows.” But the chromogenic color prints include the black along with the process’ other three customary colors of cyan, magenta, and yellow.)

The exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance” at the Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Derek Rankins. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

Ed Ruscha, Hollywood Bowl, 2301 N. Highland, from the portfolio Parking Lots, 1967; printed 1999. Gelatin silver print, 38.1 x 38.1 cm (image). Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

For images of the grids of automobile stalls in Thirtyfour Parking Lots and the portfolio of gelatin silver prints, Parking Lots, Ruscha engaged a professional photographer in a helicopter for aerial picture making. At the Ransom, the prints look something like industrial bandages stitched and slapped on a wounded earth… or like coded hieroglyphics winking messages to distant, alien observers. Interestingly, these images were often embraced by architects and urban/industrial planners as material illustrating their various concerns and positions. One item on view that used Ruscha’s parking lot images, the article “On Pop Art, Permissiveness, and Planning” by architect Denise Scott Brown, was published in a 1969 issue of Journal of the American Institute of Planners.

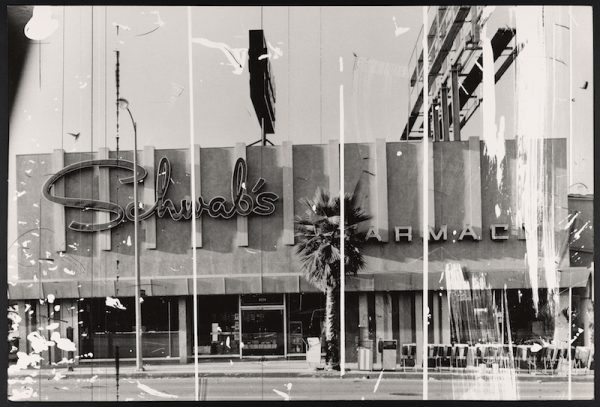

Ed Ruscha, Schwab’s Pharmacy, from the portfolio The Sunset Strip, 1976; printed 1995. Gelatin silver print, 50.5 x 74.9 cm. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Another portfolio of gelatin silver prints, The Sunset Strip, 1995, redeployed negatives from his earlier documentation of every storefront on the strip. When Ruscha first took the photos, he viewed them simply as tools or components for creating the books. By 1989, however, he had begun to see them as photographs. “Maybe because they look so old,” he acknowledged, “they’re objects unto themselves.” For the prints of Schwab’s Pharmacy, Whiskey-A-Go-Go, and other structures and institutions on the strip, Ruscha sanded and scored the negatives, creating the effect of scratchy motion picture frames. The artist has acknowledged that viewers’ association of the scratches with early cinema will diminish as analog film continues to disappear.

An early photograph of a Standard Station in Amarillo proved especially appealing to the artist for future production. “There was something new and clean about it,” he told the Wall Street Journal in 2011. “That gas station had a polished newness that I just had to draw and then paint.” Archaeology and Romance includes several Standard works. Sketches for Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half blazes a trail for the eventual (1964) oil on canvas portraying the mighty Standard as a 1946 issue of the pulp magazine Popular Western, nearly ripped asunder, flies toward the edge of the canvas.

A 1966 screenprint, Standard Station, presents the sleek dispensary of fossil fuel in blazing red signage against a murky orange that fades into a matte blue atmosphere. The modern gas pumps stand at attention, all solid and slightly military efficiency, at the ready to salute and serve the nation’s life-or-death necessity of constant motion.

The exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance” at the Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Derek Rankins. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

The exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance” at the Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Derek Rankins. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

Nearby, three 1969 Standard screenprints present a range of enigmatic gas station scenarios. Mocha Standard casts architectural elements and atmosphere with deep associations of luxurious chocolate coffee. Double Standard, a collaboration with longtime friend Mason Williams, repeats the mocha environment and places crosswise a larger, partially concealed STANDARD sign in blue. Cheese Mold Standard with Olive sets a faded blue sky above a Standard Station that appears to have survived a mellow apocalypse of moldy gray-green atmospheric cheese, as an olive orbits off like a tiny UFO.

The exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance” at the Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Derek Rankins. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

That sense of perpetual motion and the long, cinematic reach of driving through endless desert stretches of open space has, as he noted, informed much of Ruscha’s work since the age of 18. “When I’m driving in certain rural areas out here in the West I start to make my own Panavision,” he stated in the catalog for the 2011 Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth exhibition Ed Ruscha: Road Tested. “I’m making my own movie as I’m driving… .”

Ed Ruscha, Vacant Lot #1 (Anaheim), from the portfolio Vacant Lots, 1970; printed 2003. Gelatin silver print, 55.6 x 55.6 cm (image). Courtesy Harry Ransom Center

In the catalog for the 2014 exhibition, Ed Ruscha and the Great American West, at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Kerry Brougher asked the artist, “If they ever make a movie about you, who do you want to play you? Maybe we could imagine that the film has already been made, so it could be an actor from another era.”

“It was made seventy years ago,” Ruscha replied, “and it starred Harry Dean Stanton.”

*

‘Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance’ continues at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin through January 6, 2019. Three films by Ed Ruscha will be screened at the Center at 7 p.m. on October 11.

**

On sale at the Ransom Center, the volume VARIOUS SMALL BOOKS Referencing Various Small Books by Ed Ruscha, edited and compiled by Jeff Brouws, Wendy Burton, and Hermann Zschiegner consists of “riffs, revisions, knockoffs and homages” in which “artists pay tribute to Ed Ruscha’s famous photo-conceptual small books.” The volumes documented include Twentysix Abandoned Gas Stations, One Thousand Two Hundred Twelve Palms, Fifty-one US Military Outposts, Various Unbaked Cookies, Twentysix Abandoned Jackrabbit Homesteads, Some Las Vegas Strip Clubs, Fifteen Pornography Companies, 17 Parked Cars in Various Parking Lots Along Pacific Coast Highway Between My House and Ed Ruscha’s, Every coffee I drank in January 2010, and much more. There’s always more. Bruce Nauman’s 1968 project Burning Small Fires, included in both the book and the Ransom Center exhibition, consists of photographs of burning each page from Ruscha’s book Various Small Fires and Milk. One contributor trolls the artist with Various Studios and Homes Inhabited by Ed Ruscha. Texas artist Bill Daniel commemorated Dead Gas Stations, and San Francisco-based artist Keith Wilson is represented with Every Building on Burnet (burn-it) Road. Wilson writes that the busy Austin thoroughfare has been declared “the ugliest road in America.”

1 comment

This Ed Ruscha exhibition closes this Sunday, and they have now posted the interview with him: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yLjATK0QOL8&fbclid=IwAR1DiX5uBo2eeGZx2orU0vfW3JyY5X7ONFIRB2FIzVvSLldCKvdpVxgx9GI