2014: Voyager I is expected to become the first probe to cross into interstellar space this year. Nearly 38 years after launch, and over 19 billion kilometers from earth, the Voyager I probe is now the furthest and fastest moving object humans have sent to space. Exploring now for over three decades longer than originally planned, scientists don’t expect they can maintain the onboard power supply beyond 2025 when it will go silent and inert as it drifts undetectably into the darkness of deep space.

It’s well known that in space no one can hear you scream, but if you are Blind Willie Johnson, they can hear you wail. Or if you are Ann Druyan they can hear your heartbeat.

Installation view, Dario Robleto, The Boundary of Life is Quietly Crossed. Photo: Paul Hester

Back in this world, at The Menil Collection in Houston, a seventies silkscreen, Warhol’s Sunset, hangs behind the strange strangeness afforded by a collection of hybrid sea urchins carefully spread across the surface of an elegantly constructed walnut table. Made from stretched audio tape recordings (of heartbeats and retrograde space probe signals), the remains of sea urchins and lost vinyl LPs salvaged from the ocean, they function as memorials to lost signals, disappearing space probes, fading heartbeats — each a tiny shrine to human loss.

Installation view, Dario Robleto, The Boundary of Life is Quietly Crossed. Photo: Paul Hester

Titled Things Placed In The Sea, Become The Sea, this work is the centerpiece of Dario Robleto’s The Boundary of Life Is Quietly Crossed. Two of the three boundaries referred to are frontiers of human exploration — the edge of the universe and the true bottom of the sea, but the third, the interior of the human heart, is what stirs the swells and starbursts of emotion revealed by this work.

Of various sizes, these spiked and verdigris hedgehogs of the dying light are ambisemblant (simultaneously and intentionally resembling different things) — calling to mind Ernst Haeckel spirals, 16th century galleons, encrusted Christmas tree decorations, bristlecone pine trees, glass grapes, Sputnik (and its 1958 American bubble gum namesake), fool’s gold, weird Neanderthal antennas with no hope of working, petrified sponges, things found in the gift shop of the Cave Without A Name, the earth strung with lover’s pearls, porcupine profiles….one of them even looks like some obscure grandmotherly brooch. The volume and variety of the individual objects is evidence of a deep affection for the ambitious production of humanity, even including our wastefulness. The sheer amount of stuff it takes us to get things right (or wrong) is overwhelming, but this artist revels in it like someone who loves a messy child.

They clutch various emblems in their spiky grips, these urchins, including miniature Van Dyke prints of magazine/newspaper clippings, all indicative of space exploration and heart research: the 1969 moon landing, a missing mars probe, the first student-built interplanetary mission launch, a lunar eclipse, the last telemetry, in 2003, of the decades old Pioneer probe, a gaseous image of Jupiter, the first artificial heart, chest x-rays, a romanticized Renaissance cadaver, Angelo Mosso’s drawn-on-the-chest speculations about blood circulation. And many, many more. A golden glow for the entire array is afforded by several transparent, amber-hued incandescent Edison light bulbs of differing shapes and sizes dispersed amongst the objects on the table.

Not least among this dizzying array of images are the line drawings of male and female humans sent to space on the Golden Record in the 1977 Voyager I mission, which is still awaiting acknowledgement by extraterrestrials. This project, chaired by Carl Sagan, sent a long list of sounds and images into space to portray the diversity of life on earth and is at the center of Robleto’s concerns.

Detail view of Dario Robleto, Things Placed In the Sea, Become the Sea, 2013-14. Sea urchin shells and spines cast and coated with hand-ground and melted vinyl records salvaged from the deep sea, stretched audiotape recordings of various probe and heartbeat signals, soft coral, various crystals and minerals, various rock slabs, homemade crystals, various seashells, sea urchin teeth, Van Dyke prints (lost probes, probe planetary imagery, news and magazine clippings), watercolor paper, beeswax, aqua resin, etymology pins, walnut, gold and bronze-mirrored Plexiglas, glass domes, brass, copper, light bulbs. Photo: Paul Hester

One of the more curious items selected by the artist for the urchins to possess is an image of a man tattooed with a pulsar chart (coincidentally mimicking Mosso’s drawings on skin) chosen to represent a sub-culture that has arisen around Voyager I — people who ink themselves only with images from the Golden Record.

By the time Robleto gets hold of it, the vinyl salvaged by huge steel nets trolling the sea for trash is already ground to beach glass and is well prepped for his alchemical studio processes. The found records (I wonder if they include a copy of the White Album) have already lost the information embedded in the vinyl — songs lost to the sea and to the grip of barnacles who can’t be expected to care about The Beatles or whoever else may have been cut into those grooves.

And about the barnacles I can hear the voice of Werner Herzog saying, “But do they dream?”

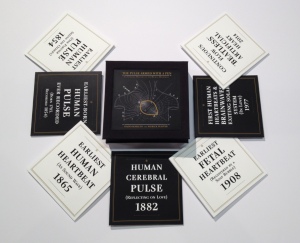

Installation view of Dario Robleto, The Pulse Armed With a Pen (An Unknown History of the Human Heartbeat), 2013–14. Custom-cut five-inch vinyl records, audio recordings, archival digital prints (record sleeves and liner notes), prints of three centuries of various human pulse and heartbeat tracings, glass slides, custom-bound book, oak, silk, engraved gold mirror, and brass. Photo: Paul Hester

Elsewhere in the gallery, the playful Anthropology Museum look of the project is continued by three built-in, glass-fronted artifact display cases. One dedicated to Machines For Observing Human Emotions, one to The Heart’s Babel and one to An Unknown History of The Human Heartbeat. By giving the work an anachronistic context, Robleto effectively announces that love and longing emanate from sediments hidden under layers of contemporary culture.

One way or another these cases are unified by attempts to make human consciousness material. The Heart’s Babel is perhaps the most central, given that the human heartbeat is certainly the center of the universe for humanity. That pulse combined with the hollow spaces of the body is the source of all music, the human activity that is a good enough reason to be here even if there is no other. Or are we, like the not-from-earth people, waiting to hear some different signal? The case contains several books created by Robleto to appear as if straight from the D.O.H. (Dustbin Of History). The knowledge that the books aren’t “real” combined with the clever titles, guarantees the effect: Never Come To Terms With Time, Hearts Succumb to Babel: Early Tracings of Love-lorn Heartbeats, The Lost History of The First Encounter of A Poet and A Stethoscope and The Sphygmograph, 1860. This last, the sphygmograph is a curious looking, attached-to-the-forearm machine meant to transform the human pulse into writing and offers Dario an excellent band name should that particular dream of his ever come true: Pulsewriter 1860.

The Machines For Observing Human Emotions case, like some odd twin in a curiosity shoppe, mirrors the arrangement of The Heart’s Babel without duplicating it, offering its own carefully devised book list: Emotionology – 19th Century Graphs of Blushes, Transcendence Through the Trace — Time Stricken Hearts, Tears That Can Never Rust and The Physiology of Faith and Fear. Both cases are completed with a multitude of related objects including borrowed prints, manuscripts, textiles, sculptures, a human skull and several tiny 19th Century daguerreotype cases, including one with a photo of Angelo Mosso and one containing a portrait of twin women and their pulse readouts framed with a dried flower.

The third case, An Unknown History of The Human Heartbeat, presents an elaborate CD Box Set, The Heart’s Knowledge Will Decay, laid out like a marketing display from Rhino or Sundazed, complete with a hardwood box, coffee table book and some confusion that may come on first glance — now which of these tracks is previously unreleased and which is already included on that other box set that came out seven years ago? But careful observation, a requirement for any art worth spending time with — casual viewers and dippers-in, y’all can go carve a heart out of wood — reveals that no two heartbeats are the same. A subset is titled The Pulse Armed With A Pen, and comes in a handsome mini-box with a photo of one of Angelo Mosso’s chest drawings on the inside and graphics on the outside which seem to draw a parallel between the inner spaces of the human interior and the orbits of more heavenly bodies.

The seven individual disks include the Earliest Human Pulse (One Partner Seeing The Other), 1854, and the Earliest Fetal Heartbeat (Registered By A Soap Bubble) 1908, but two standout from the others: First Human Heartbeats and Brainwaves Exiting Solar System (In Love), 1977 and Continuous Flow “Beatless” Artificial Heart 2014. Ann Druyan, who famously fell in love with Carl Sagan over the telephone, meditated on Love as her heartbeats and brainwaves were recorded and subsequently sent to space as part of the Golden Record. Continuous Flow “Beatless” Artificial Heart 2014, sounds for all the world like a phonograph needle left on the inner groove of a spinning record, which is appropriate given that the heart is beatless because it whirls instead of pulses, spinning blood throughout the circulatory system in a continuous flow. You might have to give in to the urge, as I did, to seek out that vocal isolation track of The Beatles’ Because, which plays the voices sans beat.

Dario Robleto, Fossilhood Is Not Our Forever, 2013-14. Fossilized prehistoric whale ear bones salvaged from the sea (1 to 10 million years), stretched audiotape of three centuries of human heartbeat recordings (1865, 1977, 2014), gold paint, concrete, rust, brass, coral, steel, glass.

Several pieces from the Menil’s collection occupy the walls, adding accents and grace notes to the overall narrative. These include a century-old bridal bouquet in a bottle, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Boys Doing Rocket Science, Joshua Mann Pailet’s Untitled (We Light the Sky, Tulsa, 1974) and Max Ernst’s Fleurs Lunaires (Moon Flowers). Another Ernst, a painting from 1928, Tremblement de terre ondulatoire (Undulating Earthquake) is placed strategically next to a fourth case, this one a free-standing vitrine balancing the room opposite the urchin table, containing a number of fossilized whale eardrums elevated on brass rods drilled into small, irregular concrete cubes stained with ocean water. Cast calcium stalactites hang from some of the cubes giving the effect of a platform that has risen from a long time in the ocean. Delicate gold threads made of stretched audio tape look like tiny telegraph wires as they connect all the eardrums to each other. Each eardrum on its pole casts its individual shadow, underscoring the connectivity with a sense of lonesome. Titled Fossilhood Is Not Our Forever, the work is an ode or homage to singers, or to those whose hearts are not yet fossils, suggesting that the first and future emissaries to any world, this one or beyond, travel by the rhythms of hearts and voices. Voices, like those of whales heard in the ocean or like that of Blind Willie Johnson, whose heart and voice are heard via the Golden Record, on some porch in space.

In the artists’ construct, the thing that outlasts it all is light, as evidenced by Warhol’s sunset looking more like a Creamsicle than a giant fiery orb on its way down. Made in 1972, Robleto’s birth year, this connection effectively counterbalances the descending sun, as certainly as the sun does rise.

Or at least this work makes me think so.

“But sometimes the wind don’t blow, the grass don’t grow and the sky ain’t blue.” Like Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground, the title of Blind Willie Johnson’s song, these famous words can be said to distill the essence of human loneliness, promises unfulfilled, the possibility that after the last signal comes back there will be silence, the sound of filaments cooling or just the last gasp of loss as we know it.

Dario Robleto is an artist that offers up some sort of hope in the face of loss. Eventually, for each of us, all is loss, but all is not lost. This work accepts the gradual fade of the signal; the gradual grind of the mill wheel and makes….bread, if nothing else. Skepticism rises proportionate to the lightness of the dough. His wish is to hold on to all that is dying, leaving, fading and to be held on to, down the line, mana mining, leaving objects vibrating with the presence of someone who was here.

Hills Snyder will be featured as the first writer in French & Michigan’s upcoming digital and print publication FAM, launching this December.

His folk-garage band Wolverton will play their first Houston gig at Notsuoh on Friday, December 6. See more of Hills’ published writing here.

6 comments

Beautifully written. Thank you.

Stunning. This piece was a beautiful journey and I feel more hopeful, having gone on it. I’m dusting off my heavily stained White Album.

Thank you, Jan Ayers Friedman. I had a lot of fun writing it.

Hey Erik, I guess we were like the bowling ball and the feather, except that we didn’t land at the same time. Nice to read your words here. You know.

Wonderful – thanks.

Beautifully described