Right Here, Right Now, currently on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston is a breakthrough. For the first time since . . . ever, the institution has chosen younger, local artists for serious solo shows in their main upstairs gallery.

The CAMH has featured current work by local artists many times in their downstairs, “Perspectives” series shows, but the main gallery has always gone to 1. out of towners, 2. themed group shows, or 3. rare retrospectives for well-established locals who have gained some national notice: Trenton Doyle Hancock: 20 Years of Drawing in 2014, Jim Love: From Now On in 2006, Nic Nicosia: Real Pictures, 1979-1999 in 1999, The Art Guys: Think Twice in 1995.

The three parts of the show are physically and thematically separate. Each was the responsibility of a different CAMH curator. Director Bill Arning selected Barrera, Senior Curator Valerie Cassel Oliver selected Donnett, and Curator Dean Daderko chose Schneider. They are three solo museum shows, and I’m going to write about them that way.

§§§§§§§§§§§

Carrie Marie Schneider: Incommensurate Mapping

Carrie Marie Schneider’s third of Right Here, Right Now, on view at the CAMH is the right here-est and now-est. Like the present, it’s incompletely digested, presenting a tossed-salad overview of Schneider’s diversified projects over the past few years, and filling the rest of the enormous space she’s been allotted with a scattershot critique of the CAMH itself via documents, models and interactive activities.

Schneider’s practice is driven by an ideology of radical sharing. She’s part of a posse of millennial culture warriors who share an evangelical project in which collaboration, exhaustive documentation, and mutual supportiveness are ends in themselves, irrespective of any concrete change or product. On Nov. 8-9, she’s co-organized charge///practicum>>>, a symposium on raising artists’ pay at Art League Houston.

In line with her ideology, Schneider is nothing if not inclusive: a shelf of books she read preparing for the show is available for visitor browsing. A sandbox-CAMH is available for visitor’s playhouse curating. Several of the miniature CAMH models in the show were contributed by outsiders, as was the giant silver CAMH balloon overhead.

Create-a-CAMH activity table a the opening reception

One wall of Incommensurate Mapping showcases relics and descriptions of Care House (2012) and The Human Tour (2013) and her ongoing walking tour project Hear Our Houston (2010-present), three project in which Schneider’s actions engage participants into aesthetic consideration of sites in Houston.

Care House video installation (still)

Schneider’s commitment to the aesthetic of sharing reached its peak in 2012 with Care House, in which Schneider prepared the home of her recently deceased mother as a memorial art installation. The piece edged several art conventions: it was only open by invitation, to one person at a time. Viewers were left alone in the house to experience Schneider’s interventions in private. Those who visited were moved. Those who, like me, didn’t want a piece of Schneider’s very personal grief could stay away. The piece defied conventional criticism, asserting an inseparable unity between the artist, the viewer, and the art.

When she’s on less personal topics, Schneider’s works tend to tiresome preachiness. The CAMH ought to be more fun; construction laborers ought to be depicted alongside well-to-do future residents in advertisements on new condo developments. Kids should curate. Walk more.

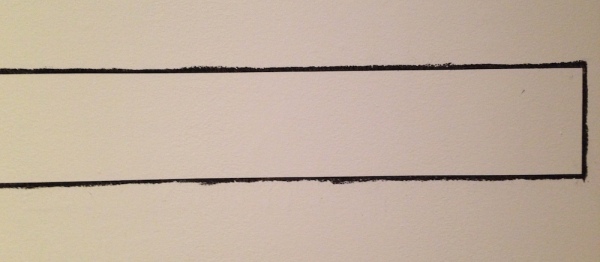

A lot of Schneider’s show is devoted to documents, activities and models that reimagine the CAMH itself. Schneider’s overall take on the CAMH is that it’s not as much fun as it could be. She acts as the museum’s conscience, reminding visitors of the disparity between the rollicking rhetoric of experimentation that characterized the CAMH’s early days, and the more decorous (and disappointing) fixture it has become. One piece, CAMH Excavation 2014, challenges these diminished possibilities directly: A 12-foot long black rectangle drawn on the wall bears the following explanation:

Inspired by the controversial and historic CAMH exhibition 10(1972), Schneider issued the museum a challenge of her own: she requested that the museum’s preparatory crew carve away the building’s walls within the demarcated rectangle in order to literally expose it’s underlying support.

The rectangle is pointedly not excavated.

CAMH Excavation, unexcavated

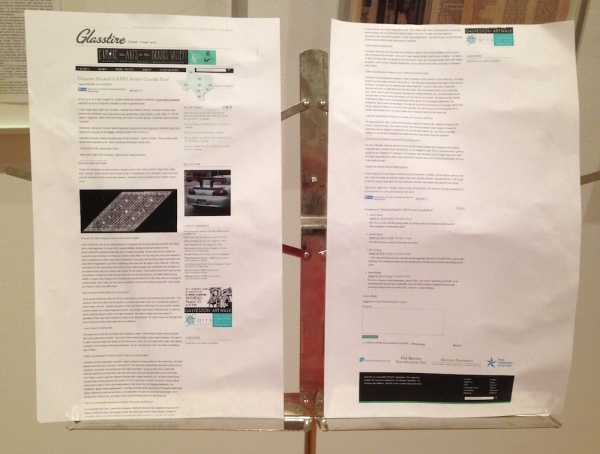

Like CAMH Excavation, most of Schneider’s institutional critique is entertaining, but a bit whiny; it points out dissatisfactions without offering real solutions. Her only direct, concrete action was against a softer target: Glasstire. On the day of the opening of her CAMH show, she inserted an unauthorized article onto this website using her access as a contributing writer, offering thirty-five year old quotes from famously hyperbolic former CAMH Director Lefty Adler without attribution, making it seem as if it they were an interview with Current CAMH Director, Bill Arning, neatly overlaying then and now, with now coming up wanting.

The Glasstire hack, as part of the installation.

Schneider is an idealist. Her passionate investment in her radical aesthetic has made her by far the most active artist of the three in the CAMH show. She’s also the most uneven, the most interesting, the most embarrassing, and the most hopeful. She’s an overeager batter continually taking wild swings at subversion, fouling ball after ball into the bleachers, in order to point out missed opportunities: in the CAMH, and in the world, using models made of Whataburger cartons to casually propose multimillion-dollar building projects.

Right Here, Right Now: Houston will be on view in the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through November 30, 2014.

CAMH model

3 comments

Hey Bill,

I made the balloon. Pietro Valsecchi and Lisa Augustyniak engineered the patterning and its breathing system.

The attribution for Lefty’s quotes are linked inside the “Interview”

Thanks

What about James Surls in 1975?

Hi Sissy,

That’s a great question.

There are a lot of greats in CAMH’s history who I decided not to focus on because they are still a force impacting the city and building their own legacies. Surls and Harithas are two examples.

Barthelme, Lefty, and Ann Holmes I found through the archives and not stories around town, so I thought they should be reintroduced to Houston now, in CAMH’s present. I’m eager to learn more and to find ways to put the generations in closer dialog. Thanks for your comment.