In the summer of 2022, I had the opportunity to see Afro-Atlantic Histories at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The viewing was quick, as it was part of a day of rapid museum visits around the National Mall, but the show had been on my radar and, even if it was a rushed experience, I wanted to pop in to see it. What first struck me about the exhibition was seeing familiar works, even some from Texas institutions, in a new, broader, richer context than what I had previously experienced.

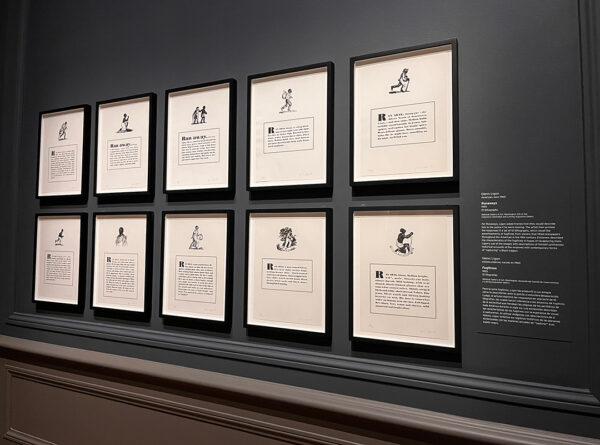

Glenn Ligon, “Runaways,” 1993, 10 lithographs. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Collectors Committee and Luhring Augustine Gallery.

I was familiar with Glenn Ligon’s print series Runaways, as the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth owns an edition of the set, but seeing this work alongside Aaron Douglas’ Into Bondage, made nearly 60 years earlier, was a poignant reminder of the ongoing ramifications of slavery and the fallacy of white supremacy. Douglas’ 1936 painting left a strong impression on me because I had always thought of his work as small-scale and intimate, yet being confronted by this five-foot square piece, featuring silhouetted figures emerging from a flora-rich environment and walking in chains towards boats at sea, recontextualized his practice. This commanding painting in particular was a depiction of the defiant hope and perseverance enslaved people carried with them as they faced unimaginable atrocities. Ligon’s Runaways takes similar imagery, of enslaved men in chains, and adds text in the fashion of ads placed by enslavers looking to identify a fugitive from slavery. The twist in Ligon’s work is that the texts were drafted by his friends; he asked them to provide descriptions of himself. While the 1993 work references 19th-century ads, it simultaneously is reminiscent of descriptions shared on the nightly news or via police scanners.

Aaron Douglas, “Into Bondage,” 1936, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase and partial gift from Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr., The Evans-Tibbs Collection.)

Second from left: Eugène Delacroix, “Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban,” 1827. Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., in honor of Patricia McBride. On view in “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Similarly, in D.C., I was excited to encounter works like Eugène Delacroix’s Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban from the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA). Rather than seeing it in the European Gallery at the DMA, where it typically resides among portraits of white aristocrats, it was refreshing to come across this image of a Black woman alongside other portraits of Black people rendered in a variety of painting styles.

When Afro-Atlantic Histories came to the DMA last fall, I was eager to revisit the exhibition with more time to consider the works; I was also curious as to how a local institution might present the show in a new way. The traveling exhibition first debuted at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) in June 2018. The original iteration boasted 450 pieces of art by 214 artists working across the 16th to 21st centuries, and was co-curated by a group of the museum’s staffers: Adriano Pedrosa, Artistic Director; Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, Adjunct-curator of Histories; and Tomás Toledo, Curator; along with independent curators Ayrson Heráclito and Hélio Menezes. In contrast, the U.S. exhibitions have featured around a quarter of the number of artworks, and each venue (the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the National Gallery of Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art) has seen its own curators step in to arrange the works for the specific institution.

The MASP has explained the motivation behind the exhibition as “the desire and need to draw parallels, frictions, and dialogues around the visual cultures of Afro-Atlantic territories — their experiences, creations, worshiping and philosophy.” Having not seen the original iteration of the exhibition, I can only imagine (and have gleaned from other reviews) that the original vision has been truncated. While there is much to appreciate about the U.S. versions of Afro-Atlantic Histories, I can’t help but pine for the fuller presentation, which at this point can only be understood with the help of the multivolume exhibition catalog. While the U.S. exhibitions are arranged into six themes — Maps and Margins, Enslavements and Emancipations, Everyday Lives, Rites and Rhythms, Portraits, and Resistances and Activisms — the MASP iteration also included sections titled Afro-Atlantic Modernisms and Routes and Trances: Africas, Jamaica, and Bahia.

Beyond the artworks in the exhibition, there is also something lost in the translation of the show’s title. Unlike the English word “histories,” the Portuguese “histórias,” similar to the Spanish “historias,” references both the idea of history and stories. The DMA does address this in some ways through its interpretive materials. In large text above a writing station in the exhibition, the museum has bilingual (English/Spanish) text that reads “Histories is plural,” and above the display section for written responses is text that reads “Histories contain many perspectives.”

Hank Willis Thomas, “A Place to Call Home (Africa America Reflection),” on view in “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the Dallas Museum of Art, 2024.

The DMA’s iteration of Afro-Atlantic Histories was co-curated by Katherine Brodbeck, the Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art, and Ade Omotosho, the Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art. The exhibition is situated in the museum’s Barrel Vault and adjacent Quad galleries, which typically showcase contemporary art exhibitions. On the exterior wall of the show, visitors are greeted by Hank Willis Thomas’ A Place to Call Home (Africa America Reflection), a large, mirror-finished stainless steel work depicting a map in which North America is connected to Africa instead of South America. The entrancing piece confronts the viewer with the connection between the continents, and places the audience as a witness to and reflection of the areas’ traumatic and entangled histories. It is a perfect entry piece to situate the exhibition, which then launches into the first section, Maps and Margins.

Works by Rosana Paulino and José Alves de Olinda on view in “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the Dallas Museum of Art, 2024.

Perhaps what the exhibition does best is intertwine art created across time and space, intentionally showcasing various perspectives and experiences. For example, in Maps and Margins we see contemporary works by U.S.-born Thomas, Brazilian-born Rosana Paulino and José Alves de Olinda, and Ghanaian Ibrahim Mahama, alongside Douglas’ Into Bondage, a 17th-century tapestry from the French manufacturer Manufacture de Gobelins, and a late 18th-century painting by British artist George Morland. While many of these pieces depict people, some realistic and some stylized, and speak to experiences related to slave ships and the transportation of enslaved people, Mahama’s textile work, AKOSUA SOM BI, employs jute sacks (which are used to transport goods) to speak about privilege and exploitation as effects of globalization and unfair trade, all of which are remnants of colonization.

Textiles by Manufacture de Gobelins and Ibrahim Mahama on view in “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the Dallas Museum of Art, 2024.

Going back to my initial experience in D.C., it was yet again refreshing to revisit familiar works in new contexts. In the DMA exhibition’s Portrait section, Delacroix’s 1827 painting Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban is presented on a wall next to Haitian and Dominican artist Firelei Báez’s Given the ground (the fact that it amazes me does not mean I relinquish it), a large 2017 acrylic and oil painting of a woman wearing a red headdress. According to the DMA’s collection guide, speaking of the woman depicted in Delacroix’s painting, “Nothing is known of her identity.” While specific information about the figure in Báez’s portrait is not discussed in the wall label, much is shared about the symbolism and references in the work, such as the tignon she wears on her head and a Brazilian good luck charm that is reminiscent of the Black Power fist. These symbols allude to the struggle for autonomy by people throughout the African Diaspora, making Báez’s work stand in sharp contrast to Delacroix’s passive portrait. Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban is, however, a necessary inclusion as it is a testament to how people of color, and specifically Black women, have been both exoticized and flattened in Western art, particularly by white men.

Works by Eugène Delacroix and Firelei Báez on view in “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the Dallas Museum of Art, 2024.

The Resistances and Activisms gallery within “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the Dallas Museum of Art, 2024.

In the Resistances and Activisms gallery, the pairing of Ligon’s Untitled (I Am a Man) text piece with former University of North Texas professor Annette Lawrence’s Rock Writing, Theaster Gates’ In Case of Race Riot Break the Glass, and Alison Saar’s Fanning the Fire II stood out as an example of works speaking to each other across time. Though I was familiar with Ligon’s and Gates’ works, the pieces by Lawrence and Saar were new to me.

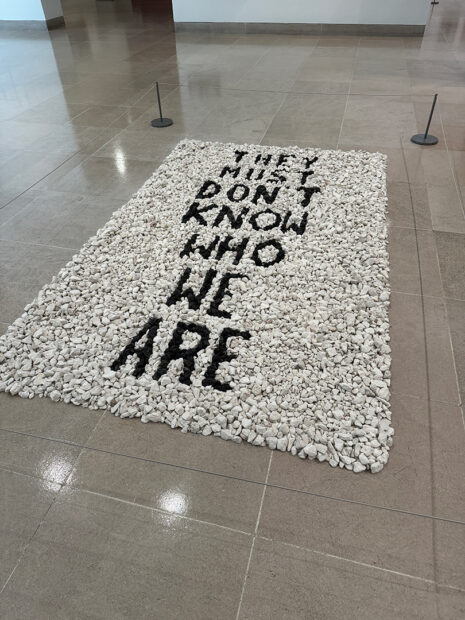

Annette Lawrence, “Rock Writing,” 1992, lava and limestone rocks. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by AT&T, New Art/ New Visions, and the Wilder Foundation.

I have encountered many of Lawrence’s works in venues across North Texas, but had never seen this lava and limestone rock piece with text that reads “THEY MUST DON’T KNOW WHO WE ARE,” which is from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s collection. It was surprising and affirming to see work included by an artist who spent a significant amount of time in the area (though since retiring she now splits her time between North Carolina and Georgia). Just as seeing works from Texas museums in this global exhibition situates our institutions in a larger cultural conversation, the inclusion of Lawrence’s work places Texas artists in an international dialogue. Made in response to the Los Angeles uprisings following the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King in 1992, the all-uppercase black text contrasted against the white stones connects visually to Ligon’s I Am A Man painting, which itself is referencing the signs carried by African American sanitation workers during their 1968 strikes in Memphis. Like Douglas’ Into Bondage and Ligon’s Runaways, the sanitation workers’ 1968 signs, Ligon’s 1988 painting, and Lawrences 1992 rock art are echoes of a continuous fight to be valued and treated fairly.

Works by Charles White and Heitor dos Prazeres on view in “Afro-Atlantic Histories” at the Dallas Museum of Art, 2024.

With over 100 works of art on view, Afro-Atlantic Histories is a heavy, rich, and beautiful exhibition. It covers a lot of ground and balances focusing on the atrocities of the experiences of people who are a part of the African Diaspora and also their joys and traditions, such as every day leisure activities, festivals infused with dance and music, and spiritual ceremonies (included in the gallery sections Rites and Rhythms and Everyday Lives). Even though the U.S. presentations are merely a fraction of the original São Paulo show, the exhibition’s origin in Brazil (a country which received approximately 46% of the 11 million Africans brought across the ocean and that was the last to end the slave trade in 1888) infuses it with a profoundly different cultural perspective, historical understanding, and range of artists. While Texans are fortunate that two of the four U.S. exhibition sites have been in our state, the DMA iteration closes in just a few weeks. This is a must-see exhibition that broadens the typical U.S. understanding of the histories, experiences, and cultures that have come from (and are still connected to) Africa and exist throughout Latin America, the Caribbean, the U.S., and Europe.

Afro-Atlantic Histories is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through Sunday, February 11, 2024.

1 comment

This is a “must-see” exhibit. Thanks for the analysis.