Last fall I was named a recipient of the Andy Warhol Foundation’s Arts Writers Grant. The funding will support the research and writing of a series of articles about Texas-based art spaces, created by and for artists of color. As I embark on this massive task, I wanted to share parts of the journey, along with tangential experiences, because in art and life it is often in the process that learning and growth take place.

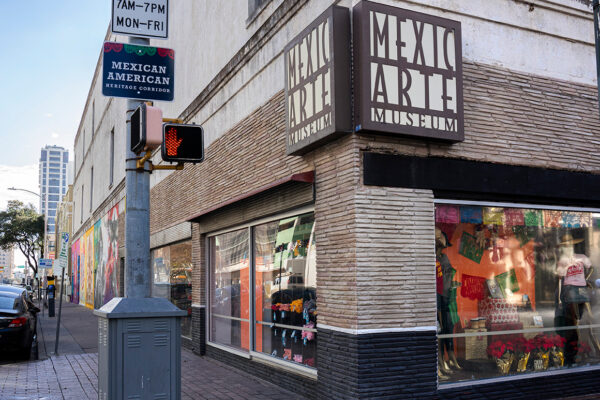

When I proposed this article series, I knew that, as eager as I am to share about newer art galleries and community spaces that have opened across the state in the last handful of years, such as East Lubbock Art House, Presa House, and Pencil on Paper Gallery, it was most important to start with venues that have a longstanding history of engaging in community-based and culturally-specific work. While I’ve been familiar with places like Project Row Houses and the Mexic-Arte Museum for a number of years, learning about their histories and legacies is both a daunting and exciting endeavor. I decided to kick off my work by traveling to Austin to learn more about the older of the two institutions, Mexic-Arte, which was established in 1984.

As a photographer, I wavered about whether or not I should take my own photographs to accompany the articles. I do have a particular interest in documenting people and places, but ultimately, I thought it would be best to work with a professional photographer who could focus on capturing high-quality, well-conceived images, leaving me to direct my energy on recording interviews and being fully present for the stories. So, I invited fellow Fort Worth photographer Raul Rodriguez to join me on the quick weekend trip.

We set out on a Thursday afternoon, planning to see some art when we arrived, before getting settled in for the evening. Friday would be the Mexic-Arte day, with about three hours scheduled for a tour, a conversation with co-founder Sylvia Orozco, and quick interviews with three current staff members. Three hours easily expanded into five, and even now I think we merely scratched the surface.

It was the perfect time for a visit, as it was the closing weekend for 40 Years of Día de los Muertos, an exhibition comprised of artwork from Mexic-Arte’s collection, illustrating the diversity of the iconic celebration and honoring the museum’s history, which is intertwined with Día de los Muertos. In its inaugural year, Mexic-Arte hosted the first Día de los Muertos parade in Austin and perhaps Texas, and now runs the largest festival of its kind in the state. Isabel Alexander Servantez III, Curator of Exhibitions and Programs; Luisa Fernanda Perez, Education Curator; and Orozco led us through the exhibition. The entry showcased a wall full of ephemera from across the organization’s 40 years of celebrating Día de los Muertos, including early photographs of the co-founders Orozco, Sam Coronado, and Pio Pulido in Mexic-Arte’s first space, a warehouse in the city’s downtown.

The small space held a depth of work, showcasing photographs of Día de los Muertos celebrations in different regions of Mexico; various ofrendas, including an Indigenous-inspired tlalmanalli ofrenda by Laura Ríos-Ramirez, a Catholic baroque altar-style ofrenda, typical of the Mexican state of Puebla, by Emmily Arenas and family, and an ofrenda honoring Austin’s lowrider community; works by significant artists like José Guadalupe Posada and Luis Jimenez; and Catrina sculptures. The back room of the exhibition was a tribute to 12 deceased artists, including the organization’s other co-founders and artists who were intimately tied to the museum’s history, such as José Treviño and Angel Rodríguez-Díaz. Pieces, mostly from Mexic-Arte’s permanent collection, from each artist were on display.

Installation view of “40 Years of Día de los Muertos” at the Mexic-Arte Museum. Photo: Raul Rodriguez.

Beyond the main exhibition was El Nacimiento, a one-room nativity, intricately composed of over 400 small pieces. The installation included a variety of vignettes depicting everyday scenes like children playing games, people cooking, and musicians playing instruments, alongside the traditional manager scene, and a corner dedicated to demons and devils in a fiery tableaux below a volcano. The scene was set-up by Oscar Guerra-Briseno, who has been a preparator, off and on, at Mexic-Arte for nearly a decade.

The tour extended to the side of the building, where Mexic-Arte commissions murals on a rotating basis through its program El Mero Muro. The most recent edition, Remembrance, was painted by Mauro de la Tierra, a self-taught painter, sculptor, and illustrator, who is a first-generation Mexican-American from San Antonio. The piece was commissioned to coincide with the Día de los Muertos exhibition. Other murals currently on the wall include Somos Ellas by Víctor Meléndez (based in Mexico and Seattle) and Tavo Garavato (based in Colombia), Tree of Life Estampilla by Austin-based Carmen Rangel, and Dreaming of Xochitlalpan by San Antonio-based Kat Cadena.

I had never visited Mexic-Arte before, so the tour was an important way to begin our conversations. It was helpful to see and understand the space and its roots with Día de los Muertos before sitting down with Orozco to dive into details of how the organization came to be. We spent over an hour talking about Orozco’s childhood, her time at the University of Texas at Austin, the scholarship program that took her to study art at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City, what brought her back to Austin, and the early days of Mexic-Arte. (All things I will go into further detail about in a future article.)

It was a whirlwind to hear these stories, and it left me with many more questions. It is common knowledge that Mexic-Arte has faced criticism in the past, both from people within and outside of the organization. And while these critiques are valid and important, the story is complicated. What is clear is that it takes a passionate group of people and, in this case, a particularly headstrong person to persevere in the difficult task of bringing a place like Mexic-Arte to fruition.

Conversations with Servantez, Fernanda Perez, and Guerra-Briseno were quicker, but provided additional insight into the inner workings of the organization. Each of the staff members spoke highly of the museum and indicated that its mission of preserving and showcasing Mexican, Latino, and Latin American art and culture was unique among arts organizations; they also noted its culture of collaboration has been a rewarding experience.

Outside of our time at Mexic-Arte, Rodriguez and I visited a few other spaces in Austin, including The Contemporary Austin, Big Medium, the Blanton Museum of Art, and Martha’s Contemporary. The Blanton was the only art space I had visited previously.

Danielle Dean, “11 p.m., 2:05 a.m., 5:10 a.m., 12:45 p.m., and 5 p.m.,” 2022, watercolor on paper mounted on Dibond. The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art, Orlando, Florida. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond.

At The Contemporary’s Jones Center, I was eager to see the current exhibition, This Land, featuring five artists from across the Americas whose work explores themes related to colonialism. Of the artists on view, Minerva Cuevas was the one I was most familiar with, as she had created a site-specific installation at the Dallas Museum of Art in 2018. I was surprised to see her sculptures featuring artificial flowers in vintage oil cans, which were so similar to paintings I had seen in Marfa last October by Kari Englehardt. Danielle Dean’s work stole the show. Both her 35.5-foot landscape painting at the entry of the exhibition and her five-channel video installation Amazon, on the second floor, were breathtaking.

Having written about Big Medium’s recent move to South Austin, it was fantastic to meet-up with the organization’s Curator and Director of Programming, Coka Treviño, who toured us through the space. It was a treat to see the studio spaces available to artists, the rentable co-working area, the 3,852-square-foot gallery, and the smaller project galleries occupied by The Projecto, an alternative space run by Treviño; Coronado Print Room, a printmaking studio and a gallery dedicated to showing print-based works; and Capitol View Arts Gallery, a nonprofit primarily focused on showcasing Black artists and musicians.

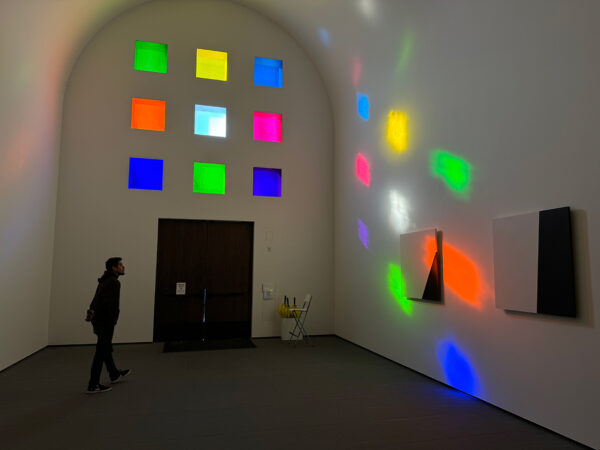

In 2022, I visited the Blanton and wrote about my experience at Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin. It was fun to revisit the chapel with someone who had never been before, but I was most interested in seeing the newly renovated outdoor spaces, including a mural by Carmen Herrera, works from the Gilberto Cárdenas and Dolores Garcia Collection, which the museum acquired last year, and Steve Parker’s Weird Winter, a temporary, multidisciplinary installation.

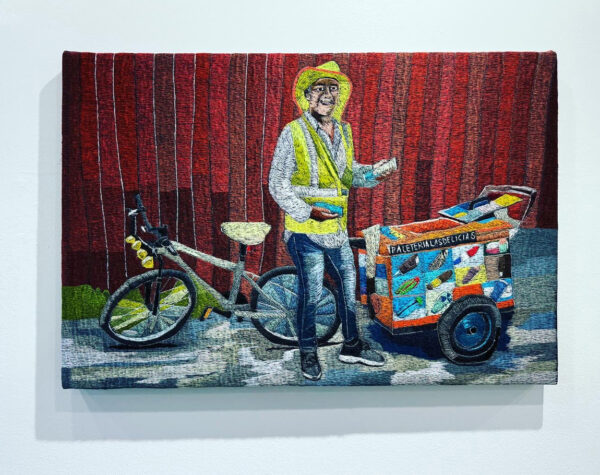

Our last stop before heading back to Fort Worth was Martha’s. Though I had never been to the gallery’s Austin location, I stopped by their booth previously at the Dallas Art Fair. In fact, the artist on view when Rodriguez and I visited the gallery was Erick Medel, whose work was featured in Martha’s fair booth in 2022. His threaded canvases captivated me when I saw them there, so having the opportunity to see more of the work in person was a nice surprise. The pieces on view were part of an Austin-specific series, where Medel created his iconic thread works on an industrial sewing machine based off of photographs of the city. Additionally, there was a small installation of photographs and ephemera from the ATX Barrio Archive.

Since returning home, I’ve had a lot to process and consider. I’ve begun the work of transcribing hours of audio recordings and researching the people, places, and organizations Orozco mentioned in our conversation. I’m looking forward to sharing more soon. In the coming months, along with furthering the Mexic-Arte article, I’ll be traveling to San Antonio to learn about the city’s Latino-founded arts organizations.