I have not attended a church regularly since I was a teenager, and I realize, in Texas, that might make me a bit of an outlier. This is partly due to my personal experiences with the Church of Christ in my youth, partly due to my inability to reconcile certain Christian doctrines, and partly because I tend to find my spiritual communing in the outdoors, through music, and in art spaces. These provide me with opportunities to consider grand questions about life, death, our place in the universe, and our duty to each other. The play between the intimacy of art and the grandiose nature of the architecture of places like The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas; and the Emma S. Barrientos Mexican American Cultural Center in Austin, has the ability to stir in me these contemplations.

And, while I know that much of the history of visual art involves the expression of religious sentiments and teaching religious texts, because of my own distance with religion, I am still sometimes caught off guard when contemporary artists make work directly inspired by religious ideology or situated in religious institutions. Of course, in certain instances, like when I visited The Marc Chagall National Museum of The Biblical Message, I knew the context into which I was walking. Having seen Chagall’s show at the Dallas Museum of Art in 2013 (which mostly focused on the artist’s work related to theater), I was excited to have the opportunity to be in Nice, France and to experience a completely different body of work by the artist.

The museum was just a short bus ride from Old Nice, where I was staying during my visit. From the street, the building is a bit hidden, and at first seemed underwhelming. However, the simplicity of the space made more sense after learning that Chagall’s intention was for the building to almost disappear into the background, leaving room to showcase his work. Additionally, surrounding the museum is a garden featuring Mediterranean plants like olive, cypress, pine, and green oak trees.

Walking in, the artwork certainly took center stage. Large colorful canvases filled with whimsical compositions, floating figures, and flowing shapes and lines felt majestic and came alive in the space. The seventeen paintings that were originally donated in 1966, by Chagall and his wife, Valentina Brodsky, hang in the main spaces of the museum.

Twelve paintings that reference the biblical books of Genesis and Exodus adorn the largest section of the building, and depict stories such as the creation of man, Abraham and the sacrifice of Isaac, Noah’s ark, and Moses and the burning bush. The overarching color schemes in these pieces are yellow, blue, and green, seemingly referencing life and growth. An additional five works inspired by The Song of Songs are hung in a smaller hexagonal room. These pieces are all painted in a similar, almost monochromatic palette featuring tints and shades of red, and depict a collection of poems dedicated to love and desire.

Some of my favorite pieces in the museum were Chagall’s iconic mosaic and stained glass works. Perhaps it was the permanence of these works or their deeper connection to the architecture of the building, but I was mesmerized. A massive mosaic, which is visible through a window in one of the galleries, depicts Elijah being carried to heaven on a chariot of fire as he is surrounded by representations of the twelve symbols of the Zodiac. This combination of biblical and pagan symbols spoke to my own spiritual leanings, which tend to combine ideas from across the belief spectrum. I wondered if, to Chagall, this choice had a deeper meaning or if the Zodiac was merely a representation of the night sky.

In the darkened auditorium, the nearly floor-to-ceiling stained glass panels of The Creation of the World cast a deep blue tone across the entire space, perfectly encapsulating both a feeling of reverence and a reminder of the museum’s location: la cote d’azur. Among the abstracted shapes and lines of these pieces are images of angels, man and woman, a snake, animals, and a body of water. Standing in the space, I felt more moved by the mood the cumulative works elicited than the narrative of their message. Chagall is quoted as saying, “For me, a stained glass window represents the transparent partition between my heart and the heart of the world.” Personally, I felt connected to the artist’s heart and intention without focusing on the specifics of the biblical stories; instead, through the work I was considering the larger themes of connectedness, trust, and sacrifice.

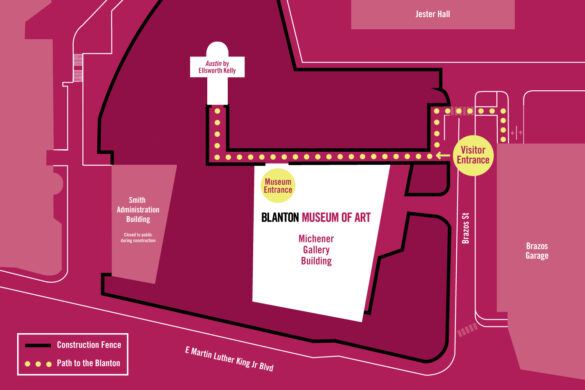

Chagall’s use of color to evoke a mood is impeccable, and in many ways brought to mind Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin at the Blanton Museum of Art. Even though the Blanton and the artist are careful not to refer to the building as a chapel, their website identifies the building’s Christian and Romanesque influence and features.

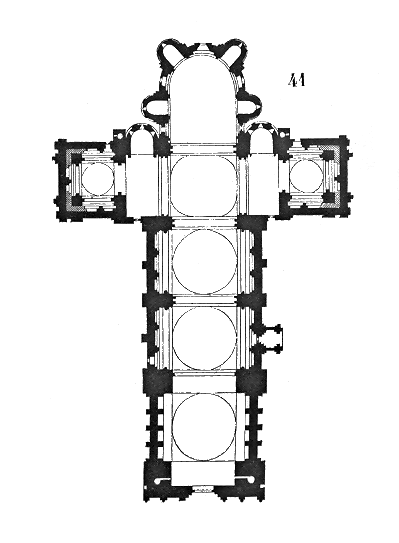

Although it is clearly much smaller than European Romanesque cathedrals, Austin follows the same basic floor plan, which creates the shape of a cross, has a rib vault in its center, and incorporates stained glass windows. The black and white marble panels hanging on the interior walls of the building, which are themselves abstract representations of stations of the cross, play second fiddle to the colorful glass works that flood the space in rainbow hues.

Three of the building’s four end caps have glass windows, and each is arranged differently. Above the south entrance is a three by three grid of colorful squares, with a white square in the middle and an assortment of other colors included in no apparent order. On the west wall of the building is a circular design made from twelve long, thin rectangular strips of glass that are reminiscent of sun rays. Starting at the top of this circle is a yellow hue, and clockwise from there the colors shift in a reverse rainbow. On the east wall of the building is another circular design that consists of twelve squares and diamonds and recalls a traditional rose window, though its center is not filled with glass. The colors of these squares mirror the piece across from it, starting with yellow at the top of the circle.

The section of the building that would be the apse does not have stained glass and instead holds an 18-foot-tall wood totem. The piece is made from California old growth redwood and seems to be a minimalist stand-in for a cross. Of the building, Kelly has said, “I hope visitors will experience Austin as a place of calm and light… Go there and rest your eyes, rest your mind.”

Kelly’s Austin and the Chagall Museum have different purposes, but just as Kelly designed Austin, Chagall worked closely with the architect and landscape designer of his museum to ensure it functioned as he envisioned. Chagall imagined a home and reverent space to present his work, and Kelly designed a space in the vocabulary of his work to be a restorative experience for visitors. Whereas the Chagall Museum provides ample (and separate) space for the artist’s paintings and stained glass, Kelly’s Austin places fourteen black and white panels in a shared space with the stained glass (which inherently becomes the focal point and overshadows the panels).

Despite their different approaches, both to art and architecture, each artist has designed a serene space for contemplation that builds on traditions and the vocabulary of religious art. Both spaces are imbued with Judeo-Christian iconography, and both also speak to larger, universal concepts — Chagall to life, faith, and love, and Kelly to time, space, and change. While knowing the narrative behind Chagall’s work or the history and symbolism of Romanesque design might add a canonical layer that provides additional context, an unfamiliarity with or purposeful disregard for that information does not detract from the experience. This is, perhaps, because even though we tend to put up distinct and unwavering boundaries on our religious beliefs, there are messages and morals that transcend religion and speak to a deeper search for meaning, purpose, and community.

Artistic and religious spaces are both deeply rooted in culture, and as religious beliefs and opinions become more and more entrenched, maybe art is one place where we can come together to reveal our common humanity. When we look across time, from the ancient past to the present day, regardless of the belief system in place, people have demonstrated an inherent need to create understanding from the chaos of life. The Chagall Museum, Kelly’s Austin, and other types of meditative spaces provide a respite from the day-to-day work/life grind and allow us to consider the big thoughts and universal questions that often feel too large to contemplate.

1 comment

Wonderful piece! Such a treat to revisit the Chagall museum in Nice. I had the lucky opportunity to go in my teens as an exchange student in France. I remember the natural setting, simple architecture, glittering sun, and splendid work all creating a unified experience. To my young mind, it was exciting, illuminating, transcendent. I think it rooted art in my consciousness and spirit as the place to look for enlightenment. Thanks for this lovely, thoughtful reminder.