Author’s Note: This is the second in a series of articles that recounts my experiences as a Fulbright Scholar in India. I recently returned from the first of three trips. I spent a month in Ahmedabad/Gandhinager, three weeks in Kolkata, and my last week in Goa.

In part one of this series, I spoke about the Fulbright process and wrote about three artists whose work explores gendered identity. Part two continues the discussion, centering on four more artists’ work that explores diverse aspects of boundaries and borders, utilizing a variety of materials and processes.

Kolkata artist Riti Sengupta’s work looks at issues of gender, domesticity, identity, and memory. She is an alumni of my host organization, the National Institute of Design (NID), in their masters of photography program. Her photographic series Things I Can’t Say Out Loud began during the pandemic, when after eight years away, she returned home to live with her family during the lockdown. The series came out of conversations with her mother about the dominant patriarchal structure within her family and the additional pressures/labor that placed upon her mother, despite the fact that her mother works full time as a doctor. The conversations usually occurred over meal preparations and clean-up; these later led to a series of photographs with her family members as subjects.

Unlike Sengupta’s previous documentary work, these staged photographs are performative, with the subjects enacting metaphoric and symbolic gestures for the camera. In one image, the artist’s mother sits in a chair with seven stacked pillows on her lap, masking her body and face. With her feet barely touching the floor, the image speaks to the invisibility of labor and constraining domestic roles placed upon females. The pillows appear to be suffocating her, despite their lightness.

In another image, Sengupta’s mother is hugging her son. Her body blends into the dark background with only her arm visible. A large cotton “cloud” shrouds her face. The photograph illustrates the importance of sons within a family’s hierarchical structure. Again, the mother’s identity is hidden, symbolizing her sacrifice for her children. The images hint at underlying violence, but also absurdity, pointing to unrealistic expectations as well as the loss of individuality for a woman in her role as caregiver. Sengupta’s work challenges the prescribed boundaries for gender roles and uses visual language to suggest the possibility of redefining such roles.

Another Kolkata artist, Moutushi Chakraborty, also addresses themes of identity, home, as well as homeland in her work. Trained as a printmaker, Chakraborty incorporates drawing, painting, and other mixed media into her prints. Her series Memoirs as Letters explores family history through the lens of migration. The works are inspired by postcards her grandfather’s family in Bangladesh sent him during his studies in India. The artist shared with me her family’s legacy of the 1947 Partition of India. Chakraborty stated, “Despite 76 years of independence, the horror and trauma of forced exodus remains immortalized through personal anecdotes shared from generation to generation.”

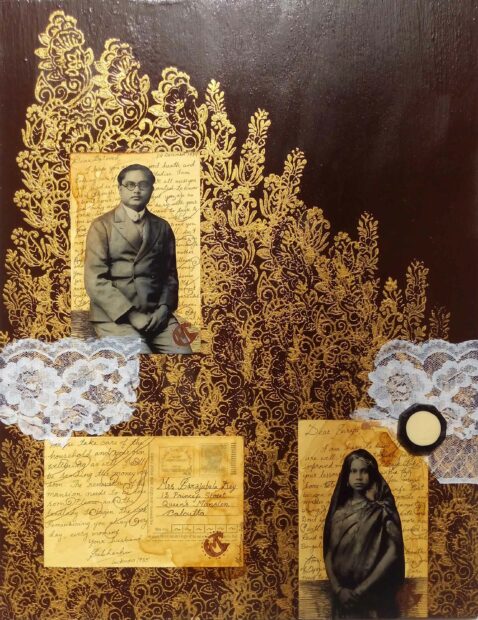

In Memoirs as Letters—V, two portraits — a male and female — are juxtaposed against aged, fictionalized postcards. The background, an intricately painted gold lace filigree pattern with swatches of white lace and a button, references domesticity. The floating figures are cut out from their original backgrounds, symbolizing displacement as well as the loss of home and identity. The fabric remnants speak to loss, alluding to the fact that so many people fled leaving their belongings behind.

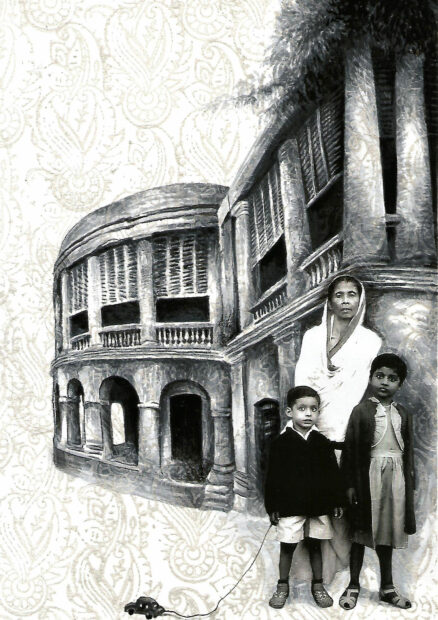

Chakraborty’s Homeland series addresses voluntary migration and the vanishing historic architecture in North Kolkata. Oftentimes, families either cannot maintain the upkeep on historic ancestral homes or choose to leave for better opportunities elsewhere. New modern buildings replace the old architecture. In Homeland—III, a woman and two children stand in front of a columned home. Like the previous series, the background features an intricately printed traditional pattern referencing fabric/clothing/homelife. The figures, as well as the building structure, are floating in space, unrooted from the earth. The series serves to memorialize the historic architectural gems of the past.

Moutushi Chakraborty, “Memoirs as Letters V,” 2018, collage, ink, acrylic, button and cotton lace on postcard pasted on plyboard, 18 x 14 inches.

I met artist Mallika Das Sutar at her home in the artist collective Chander Haat, whose mission is to provide a space for artists that inspires freedom without barriers, encourages interdisciplinary research, creative experimentation and a commitment to community engagement. In my mind, it seems like an artist’s utopia. In reality, it takes tremendous dedication, sacrifice, as well as money to maintain a collective that functions outside of the mainstream art world.

Sutar and I had discussions about injustices against women, her work surrounding gender violence, as well as her investigations into the land. Her interdisciplinary work spans many media — drawing, sculpture, performance, and sculptural installation with a focus on social practice with the neighboring community.

In the installation, I Can’t Bear It (2019) from Sutar’s exhibition There Is Nothing Natural or Inevitable About Violence Against Women, the artist stitched the three-word phrase across three panels, using her hair as the thread. It is a visceral proclamation against gender violence. Hair is a recurring material in many of her works. In this piece, she uses it to express her angst and grief, but also as a challenge to men who target women. Hair is a symbol of beauty in many cultures, but to Sutar it symbolizes strength.

In her Untitled performance work from 2021, she uses her body as a metaphor for the limitations and boundaries of female existence, but also as a tool for resistance. The performance took place during the pandemic, coinciding with farmers’ protests over their struggles to farm the barren land. In the performance, she is dressed all in black and her hair is shrouding her face. She carries a shovel full of grass over a rocky terrain. The public was encouraged to participate — to bring ceramic shards and bits of grass to place on a second figure lying on the ground. This ritualistic act symbolizes the reliance on the land for life. When the land is no longer able to produce crops and food, the body cannot thrive. The work illuminates the interdependency between the body and the land. The end shot poignantly portrays the artist lying next to the other figure, in a gesture that could be interpreted as a symbolic burial or a sacrifice to the earth.

Like Sutar, Goa fiber artist Gopika Nath also has a deep connection to the land. She takes weekly beach walks to forage, using her found treasures in her sculptural fiber practice. Nath’s creative practice resonated with me, especially her innate curiosity about the natural world, as well as her commitment to healing — herself as well as the earth.

Nets are a recurring motif in Nath’s work. She has a series called Thoughtnets, which began during the pandemic when she shifted from embroidery and crochet to knitting as a cathartic tool. Although she wasn’t consciously creating specific forms, they emerged into three-dimensional sculptures. Nets symbolize entrapment. Relating this to our thoughts, we can become trapped by our negative thoughts/fears, and our attachment to materiality. A net can also serve as a vessel for containment or protection. Nath also began photographing objects from her beach walks and creating netting over them, interspersed with embroidery and beading. I interpret these as a field of protection over the natural world. A small defiance against the destruction of the environment, especially sea life.

Embroidery, crochet, knitting, and stitching — and the whole of fiber arts — has historically been thought of as domestic work, and therefore has not been included within the larger context of the contemporary art world. Nath’s work challenges these notions. Nath and I also discussed her approach to slow time. I wondered if her process was in fact a rebellion against the fast-paced digital world we live in. She responded that it is not an act of resistance, but rather a strategy to anchor one within oneself, to be consciously reflective.

One of my takeaways from my time in India thus far is the common theme of gender discrimination. Artists in the West have experienced this for decades, but it is extra challenging for female artists in India. There are tremendous societal expectations of fulfilling the role of wife, mother, and daughter-in-law, combined with an emphasis on pursuing careers such as medicine or engineering, rather than art. Many students shared with me that their parents were disappointed that they were pursuing a degree in art. Many had received undergraduate degrees in other more “reputable” fields before pursuing art. The caste system adds another layer of oppression; it’s not something easily defined, since it is so ingrained into the culture. Friends have said to me that it technically no longer exists, but as other people have pointed out, only someone from an upper caste could have the luxury of making that statement.

In future articles, I will share the work of some of the NID students who are committed to community and social activism, as well as highlight the story behind the largest public art festival in the world.