In part one and part two of this series, I wrote about the interesting female artists I have met while in India on a Fulbright scholarship. I have been analyzing how their work explores themes of gender, identity, migration, the environment, and homeland. This article focuses on student work. I spent my first month at my host organization — the National Institute of Design (NID) in Gandhinagar, India, working with photography students in the Master’s program. NID is the most renowned art institution in the country and only selects a handful of students each year.

I taught an anthotype workshop as well as a professional practices writing workshop. While I have a lot of experience in 19th century alternative photographic processes, I am not prolific with anthotypes. They require very long exposures in direct sunlight, as well as a lot of patience. The technique uses organic materials to create an emulsion on the paper and does not require any toxic chemicals for processing. The students experimented with a variety of materials, finding success with turmeric, beet root, and henna. We experienced rain during the workshop, which impeded the exposure process, but the students managed to exhibit a final print in a gallery exhibition, showcasing their work together with an installation of my solar plate etchings and chine collé prints.

In addition to the workshops, I had the opportunity to do one-on-one review sessions with the students. I was very impressed with the depth and breadth of their work, as well as their commitment to socially engaged themes, nuanced storytelling, and empathy for their subjects. I arrived mid-semester, as they were working on their Design 2 projects. During the first year, the students chose a subject and created a series of documentary photographs. Using the same subject/community, the Design 2 project included a multimedia component. Featured here are glances at four student projects.

Chandrika Kadiya and Bina Patel wait for their afternoon meals while Aniba Sutariya and Naina Raval share their lunch. Aniba Ba detests having to eat alone which means she often looks for someone to share a meal with; and as she is adored by all the residents of the shared room, it is barely ever an issue.

Sushmita Sarkar’s work documents a senior-care facility in Ahmedabad. The series, entitled Alongside Autumn, focuses on capturing the daily rituals and intimate, mundane moments of the facility’s residents. Although assisted living and nursing homes are quite common in the United States, they are not as prevalent in India, due to the long tradition of communal family living and the cultural norm of caring for elderly parents in the home. When Sarkar and I spoke about her time at the facility, she told me that many residents didn’t receive a lot of visitors, so they were happy to have someone to talk to and share their stories.

Parameshwaran Purushottham T., 88, got himself an induction cooker solely to abide by his 4 am habit of having morning tea. He often mentions that this habit of his helps him set the day ahead right.

Sarkar’s Design 2 project, a short film entitled Birds of the Eventide, is a departure from traditional documentary structure, offering an audiovisual journey through the lives of residents in the same senior care facility. The beautifully crafted film utilizes poetic and visual elements to capture the slowness of time and convey the essence of the residents’ lives. The opening shot is a close-up of a hand rising and falling with each breath, communicating the cycle of life and death. Another transitional shot of the figure’s shadow framed with golden afternoon light evokes a contemplative tone. Voiceover clips provide insights and stories into the lives of the individuals.

Both projects underscore the loneliness and isolation that the residents experience, and raises awareness about the shifting dynamics of elder care. The work emphasizes the importance and need for human connection.

Asha Solanki, a 79 year old resident, makes sure to religiously apply a few drops of oil to her hair every morning while she neatly ties it in a sleek braid.

Shravya Mishra’s and Shifa U P’s work addresses issues of gender discrimination and inequality. Mishra’s Design 1 & 2 projects, entitled Billa Number, document the female train porters of the Bhavnagar train station in the state of Gujarat. Historically, the porter is a male-only licensed position, but in the 1880’s, the King of Bhavnagar gave women the right to work as porters. Porters receive a license, which can be passed down to subsequent family members. In all of India, this is the only train station that employs female porters. However, as train travel is in decline, there is now only one train each day, so women porters struggle to earn a living and often work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

“I started working as a coolie after my mother met with an accident… she can’t walk, she fell down while running to work at the station… but it’s okay, we live a good life, I also work in the office at the station. A year back we made a new house, and I took out a loan.” -Lata Ben Krashan Bhai Chudasama

Similar to Sarkar’s film, Mishra also uses clips of voice-overs from the women to tell their stories, which adds an additional layer of depth and intimacy to the work. Their voices serve to humanize the subjects, while giving the women agency in how their narratives are told. Mishra’s photographs and short film show the contemporary challenges faced by the female porters, including their economic hardships. The work reveals how these women are overcoming discrimination by breaking through traditional gender barriers. The sensitive portrayal serves as a testament to the women’s resilience and determination, and acts as a document for a future legacy of empowerment.

Shifa U P’s photographic series, Invisible Threads, intimately examines the lives of self-employed Muslim women in the textile handicraft sector. In India, Muslim women often face discrimination due to gender disparities, limited access to education and work opportunities, and because they are part of the minority religion. U P prints the photographs on fabric, and the women add stitching to the images. The choice to print on fabric provides additional context to the work because the materiality of the fabric adds a physical and tactile dimension to the image, illuminating the relationship between the subject and the textile industry. The stitching allows for a true collaboration between the artist and her subjects.

“We get money during the festive season, like in November during Diwali because more people travel, but other than that there are days when there is no work. I get up in the morning at 5 and do the household chores, offer prayers to the lord, have tea and then leave for work. During the day I work in shops… I fill water for them and do other cleaning work, in the evening at 5:30 I go to the station to work.” -Lalita Ben Bharath Bhai Mathiya

Like Mishra’s work, U P’s work explores themes of empowerment, overcoming gender inequality, and challenges patriarchal traditions. I was especially drawn to the images of the women’s hands as they work with the cloth, whether in block printing, stitching or embroidery. The hands serve as powerful symbols for skill, labor, and creativity, providing the viewer with an inside glimpse into the women’s daily work.

Unlike the other three artists, portraiture is not central to Muskaan Gupta’s work, which delves into the landscape as a site of contested history and violence. The archeological site of her research is Rudra Mahalaya/Jami Masjid Complex in Siddhpur, Ambavadi, whose history is filled with hundreds of years of religious bloodshed and devastation.

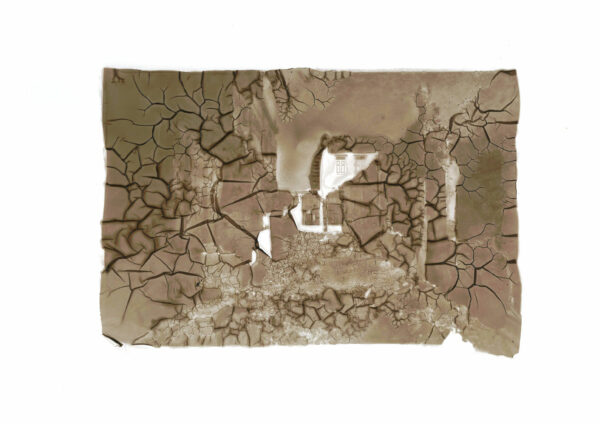

Gupta uses soil from the site as material for her work. The two-part project, entitled Memories of a Ruin, includes cyanotype prints on terracotta slabs made from the site’s soil. In part two, Conversations with a Ruin, Gupta uses the 19th century transfer carbon process to print images taken of the site, using collected soil as the pigment. The experimental nature of the process allows for cracking and a fragmentation of the image surface. In this way, the process visually depicts the degradation of the site and its ghostly remains. The choice of material symbolizes the deep-rooted history embedded into the landscape, connecting past with present. Quite literally, the soil serves as a vessel containing the residue of generations of violence and conflict — a witness to horrific historical events.

The work of all four students brings awareness to important societal issues, and also fosters broader dialogues.

My time at NID re-energized my passion for teaching. Prior to this, I was suffering from burnout after a decade of teaching at a community college where the majority of the students were unmotivated, uninterested, and lacked the basic skills to engage in critical thinking and writing. What separates this group of students from many others that I’ve witnessed and/or taught is their commitment to social issues and desire to affect change in their communities.

In my last article, I will explore the Durga Puja Festival in Kolkata — the largest public art festival in the world.