Photograph of Octavio Medellín sculpting “Mazatlí-Tecutli (Lord Deer),” 1995. Photograph: Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

Part 1 of my review of the outstanding Octavio Medellín (1907-1999) exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art left off with Genoveva of Brabante (1948-49), the seven-foot-high statue of a woman holding a deer in the left foreground of the above photograph.

I begin this final part of my review with the artist’s masterpiece, The History of Mexico (1950), visible in the center of the above photograph. I follow with Conceived (1949-1950), which is on the right side of the above photograph. After that, I continue through the passageway to the second half of the exhibition.

Medellín’s Later Wood Carvings

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (photograph with all four sides), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, 87 x 18 x 18 in., Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (from exhibition catalog).

Carved from the same enormous mahogany log as Genoveva of Brabante, History of Mexico is a tour de force, wrap-around relief carving that encapsulates Mexican history from the time of the Toltecs and the Maya (in the bottom right) through the post-Mexican Revolution reconstruction era (top tier). It is nothing less than a symphony in wood.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (photograph with all four sides of the lower tier), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (from exhibition catalog).

On the far right (1.4), a putative Toltec ruler stands on a reed bundle that represents a Mesoamerican century of 52 years. It symbolizes indigenous history (most of which was wiped out when the Spanish burned nearly all pre-Hispanic books). A hand is visible near his foot.

In the next scene, two subjugated Maya elites with feather headdresses (1.3) bow down to the Toltec lord (who is around the corner to their right). The hand near his foot that we saw in the first scene belongs to one of the subjugated Maya.

Note that three long branches seem to extend all the way across the four sides of this relief. They may have been inspired by Crossing the Barranca, a mural panel painted by Diego Rivera in the old Cortés palace in Cuernavaca in 1930. In that mural, a horizontally inclined tree offers passage across a deep gully. The branch in the lower register of History of Mexico seemingly incorporates or becomes the Toltec lord’s extended right arm. Perhaps what appears to be a branch on this lower register is actually a snake, identifiable as Quetzalcoatl, the mythic feathered serpent, as well as Quetzalcoatl, the man and priest, identifiable as the Toltec lord on the right, in whom the snake terminates.

In the middle of the twentieth century, it was generally believed that the Toltecs (from Tula, in the modern state of Hidalgo) had conquered and influenced the Maya in Chichén Itza. As noted in Part 1, Medellín had visited and studied Tula as well as Maya sites in the Yucatán. The Aztecs revered the Toltecs, whose very name was synonymous with art (though their work does not compare favorably with that of the Aztecs, nor with that of the other major cultures of Mesoamerica).

To the left of the Mayan figures, one can see the palm of a raised hand. It belongs to the Aztec goddess Coatlicue (“she of the serpent skirt”), who is on the other side of the sculpture (1.2).

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (detail of Coatlicue), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Coatlicue is the skull-headed figure with two severed hands and a skull dangling on her chest. Her own two hands (one of which is next to the Mayan figures) are upraised in a threatening gesture. Coatlicue is a death goddess, as well as the mother of the Aztec patron god, Huitzilopochtli. To her left, a large jaguar appears to be leaping from the branch (or snake). Jaguar warriors, along with eagle warriors, were the highest order of Aztec warriors. They were entrusted with capturing high-ranking prisoners for sacrifice, which was considered necessary to feed the sun. Beneath the jaguar, one can see the legs of a reclining figure (bent at the knee), as well as part of a standing figure.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (detail of Sacrifice to Hiutzilopochtli), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

As we turn the corner to view the fourth scene in this lower register (1.1), the reclining man is revealed to be a sacrificial victim who is propped up on a sacrificial stone. He screams as his heart is cut out by the priest who stands over him. In this detail, one can see how stylized the figures are, and how roughly they are carved. Note also the expressionistic elongation of the victim’s right arm, which itself resembles a long, twisting branch.

The big branch that demarcates the lower register terminates in the rattles of a snake (Quetzalcoatl is a rattlesnake), which is why I think Medellín is at least suggesting that this form could be Quetzalcoatl, rather than a mere branch. This god — in effect — branches across Mesoamerican cultures, forming a bridge from the Toltecs and the Maya to the Aztecs.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (photograph with all four sides of the second tier), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (from exhibition catalog).

Medellín’s narrative resumes in the second register (2.1) with an image of Hernán Cortés on horseback. He represents the Spanish conquest. Two smaller conquistador heads and a tiny horse head are visible in the background.

The next scene (2.2) contains the head of Cortés’ horse, as well as a friar with arms that are so outstretched that he takes on a cruciform configuration. (Compare his pose to that of the cruciform figure carved on the base of The Spirit of Revolution, which I discuss in Part 1.) If Cortés represents the military and political conquest of Mexico, the friar represents the religious conquest, which was first undertaken by Franciscans.

The friar’s left arm, which bears a cross, extends across the adjoining panel (2.3), where it is superimposed over cowering indigenous figures, who are on their knees. The beaded form behind the friar’s right hand (2.2) could represent a rosary. Medellín called section 2.3 “The Establishment of Christian Churches.”

The next section (2.4) represents the Inquisition. An apparently naked man with bound, upraised arms is about to be burned at the stake. This repetition of motifs reinforces my reading of At the Stake, which, as I note in Part 1, looks like a man who is to be burned alive, rather than merely whipped. The kneeling figures in section in 2.3 no doubt fear this man’s fate. Part of a kneeling figure and a side view of the cross can be seen in section 2.4 on the left side of the bound man.

A small, skeletal figure is on the right of the bound figure. Its skull is partially tucked behind the bound man’s chest. One can make out several ribs, and a deeply incised spine that terminates in very schematic hips. This skeletal figure holds what I interpret to be a shield, such as those used by Mesoamerican warriors. Consequently, this figure is a symbol or spirit of vanquished warrior ancestors. (As noted in Part 1, Medellín was partially of indigenous descent.) If we look below the skeletal figure, down to the first register, the headdress of the Toltec lord resembles stylized flames that could have burned off his flesh. Such flames will — in due course — consume the bound man. Thus Medellín depicts not only the prelude to one of the most horrific capital punishments, he also renders its aftermath. All the while, he skillfully links images on adjoining areas of the sculpture. The cross and kneeling figure are visible on the left, the headdress below suggests flames, and the bound man’s raised hands extend to the revolutionary scene (3.4) above.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (photograph with all four sides of the third tier), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (from exhibition catalog).

The bound man’s helpless hands are an indictment of the cruelty of the ruling establishment. They incite and witness the Mexican Revolution. The revolutionary raises his rifle with his right hand. It extends halfway into section 4.4., the corn harvesting scene above it. The revolutionary rests his left hand on his crotch. His disproportionately large index finger takes on a phallic quality, which — in contrast to the helplessly bound hands on either side of it — emphasizes the potency of the revolution and its connection to fertility. The Zapatistas called for “Land and Liberty,” and the corn harvest (after land redistribution) is one of the fruits of that revolution.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (detail of church and hanging), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph:Ruben C. Cordova

On the left side of the third register, in a scene called “The Militant Church,” a man is hung by the neck in close proximity to a Christian church. Flames are evident to his right. The young man’s head is very similar to that in The Hanged (c. 1939), discussed in Part 1. But this young man’s body is so elongated and stylized that it recalls the terracotta Ecce Homo (1953) rather than the shirtless body of the young man in The Hanged. In this detail of The History of Mexico, we cannot tell whether the young man is naked or robed. The combination of hanging and burning recalls a small scene carved in relief on the base of The Spirit of the Revolution (discussed in Part 1).

As noted in Part 1, Frank Paxton, the Missouri lumberman and owner of the mighty log from which The History of Mexico was carved, objected specifically to Medellín’s plan to include the content that would appear in scene 3.1. In a letter to Medellín dated July 12, 1949, Paxton told the artist:

An afterthought I have had with regard to the one scene, i.e., the conversion of the Indians to Christianity, I believe we will omit that part where they tortured them. In other words, if they didn’t acknowledge Christianity, they hanged them. No doubt that is true, but some people may resent being reminded thereof.

Medellín, of course, ignored Paxton’s efforts to censor his piece. As noted above, he included the scene of a man about to be burned at the stake (2.4) during the Inquisition. Additionally, the next scene, “Flaming Revolt and the Misery of the Young” (3.2), depicts scenes of intense suffering that preceded the revolution. This jumble of bodies recalls depictions of damned souls made in European art of previous eras. The fire visible in the left section of this scene also laps near the hanged man around the corner in scene 3.1.

In scene 3.3, Medellín depicts General Pancho Villa (with bandoleers), General (and later president) Álvaro Obregón, and Francisco Madero, who initiated the revolution, but whose presidency was short-lived. I discuss conditions that led to the revolution in Part 1. I list some of the main events below.

Madero ignited a revolt against the long-reigning dictator Porfirio Diáz from San Antonio in 1910. Madero induced Villa, who led the Division of the North, to join the revolution later that year. Díaz went into exile in 1911. Madero was elected president in 1911, but he quickly lost the support of those who wanted immediate reforms. Zapata, who regarded Madero as a betrayer of the revolution, announced his “Plan de Ayala” in November of 1911 and began collectivizing land. Crucially, Madero was also opposed by the U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who demanded unyielding support for U.S. business interests. Wilson helped hatch a plot against Madero, who was overthrown by General Victoriano Huerta and executed in 1913.

Obregón fought with Venustíano Carranza against the usurping President Huerta. The peasant generals Villa and Zapata allied against Huerta, who only maintained control in the vicinity of Mexico City. The newly elected U.S. President Woodrow Wilson opposed Huerta. He sold munitions to the constitutionalist forces and occupied Veracruz for six months to prevent Huerta from receiving armaments from Germany. Huerta resigned the presidency in November of 1914. In 1915, the “Year of Hunger,” Carranza controlled Veracruz, Obregon controlled Mexico City, Villa controlled Chihuahua, and Zapata controlled Morelos. In 1916, Zapata and Carranza fought dramatic battles.

As a general, Obregón promulgated progressive policies, including anti-clerical measures. He helped draft the 1917 constitution and also served for a time in Carranza’s cabinet after the latter was elected president. Carranza’s forces assassinated Zapata in 1919.

Obregón came out of retirement to lead a revolt against Carranza when the latter became increasingly reactionary. Carranza was assassinated in 1920. Obregón, who was elected president in 1920, permitted peasant and worker organizations, and he also appointed José Vasconcelos, who made significant educational reforms and also initiated the Mexican Mural Renaissance. Obregeon only won U.S. recognition by promising not to nationalize the holdings of U.S. oil companies in 1923. Villa was assassinated in 1923. After retiring again, Obregón won the presidency again in 1928, but he was assassinated by a Catholic zealot.

Lázaro Cárdenas, elected president in 1934, consolidated his power by 1936, after which he began enacting reforms for which many revolutionaries fought. These reforms will be discussed below, in connection with the fourth tier of Medellín’s The History of Mexico.

I have already discussed section 3.4, which is called “Uprising of Oppressed People.” I would like to note that the revolutionary soldier is shouting or singing, like the soldier in The Spirit of the Revolution, as discussed in Part 1. Perhaps these are Zapatistas, since the upraised rifle extends into the space of the corn harvest.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (photograph with all four sides of the fourth tier), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (from exhibition catalog).

The top tier, which is devoted to the theme of “Reconstruction,” begins with “Natural Resources — Oil,” on the left in section 4.1. Cárdenas nationalized railroads in 1937; he nationalized the oil industry in 1938. It was a propitious time to take such actions. On the brink of World War II, the U.S. was greatly concerned that Latin American countries might ally with what became the Axis powers. Consequently, there was little risk of U.S. interventions on behalf of corporate interests of the kind that have plagued the world since the U.S. became a global power.

Scene 4.2 is called “Decline of European Influences.” It is comprised of tumbling elements belonging to classical architectural columns. The most direct source is José Clemente Orozco, who used this motif many times, commencing with The Destruction of the Old Order (1926), painted in the National Preparatory School. As noted in Part 1, Medellín met Orozco when he traveled to Mexico in 1929-30, and he would have been familiar with this mural. Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Frida Kahlo were among the eminent Mexican artists who also utilized classical forms in a critical manner in their paintings.

Stephanie Lewthwaite argues that the narrative of Medellín’s History of Mexico “constructed through a series of undulating, protruding, and entwined figures representing different eras,” expresses “an Aztecan understanding of time as cyclical and forged from ‘opposing forces’” (“Modernism in the Borderlands: The Life and Art of Octavio Medellín,” Pacific Historical Review: Vol. 81, No. 3 (August 2012), p. 355).

During Díaz’s dictatorship, most Mexican elites were Francophiles: they spoke French, dressed in continental fashions, ate French food, and imitated French boulevards and architecture. They looked down on Mexican (indigenous, mestizo, and popular) traditions, customs, and cuisine. Most of these elites were viciously racist, anti-indigenous Social Darwinists. Some thought the extinction of the indigenous peoples would “improve” the Mexican “race.” Consequently, motifs like collapsing classical columns had special meaning in post-revolutionary Mexico. After the revolution, indigenous, mestizo, and popular cultures were celebrated as the repositories of national essence. Concomitantly, the wholesale imitation of European traditions was now condemned.

Section 4.3 is called “Schools and Education for the People.” It features students. The young man in the center holds several books. This scene reflects the revolutionary transformation of education in Mexico. As Louise Schoenhals notes: “The purpose of education was changed from that of Europeanizing the upper classes to raising the masses from their abject poverty and morass of ignorance and illiteracy” (“Mexico Experiments in Rural and Primary Education: 1921-1930,” Hispanic American History Review 44: #1, February 1, 1964).

Outreach to rural areas (which had been largely ignored during Díaz’s long reign) was a significant initiative during Obregón’s presidency. It was perhaps the most critical development in education reform. Schoenhals emphasizes Vasconcelos’ “apostolic zeal,” under which “the whole country found itself swept up in a crusade for the abolition of illiteracy, the betterment of economic conditions, and the enjoyment of life through art, libraries, and music.” Vasconcelos also established Open Air Art Schools in Mexico, which must have been the inspiration for the Open Air School that Medellín attended at least once in Bandera, Texas (as documented by a photograph from 1927 that Castro reproduces in the exhibition catalog). In three years, under difficult circumstances (including the Huerta rebellion), Obregón and Vasconcelos created over 1,000 federal rural schools (none had existed before). Vasconcelos believed that national unity required the education and participation of all social classes. His philosophy served as an inspiration to his successors, particularly Cárdenas. The latter prioritized rural instruction and secularization, and he promulgated socialist education in Mexico’s public schools.

As noted previously, section 4.4 depicts the corn harvest. Two men harvest corn with machetes, while the rifle held by the revolutionary in the scene below enters their space. Meaningful land redistribution was brought about by president Cárdenas, who gave peasants almost twice as much land as the total amount redistributed by his predecessors. When Cárdenas’ presidential term ended, previously landless farmers possessed half of the nation’s land that was under cultivation. Peasants were also granted new access to loans. Cárdenas incorporated peasants and industrial workers into the government party. More than anyone else, Cárdenas realized the goals of the revolution and of the Constitution of 1917. Yet, as Charles H. Weston Jr. argues, through various actions, including the choice of his successor, Cárdenas also set the stage for the more conservative period that followed his presidency (“The Political Legacy of Lázaro Cárdenas,” The Americas, December 11, 2015).

The large branch that winds across the upper section of Medellín’s sculpture seems to terminate in the machete-bearing worker on the far right of scene 4.4. Somehow, the lower body of this worker seems to reconstitute itself as a log. This development in scene 4.4 parallels the log or snake that terminates in the Toltec lord at the very bottom of this side of the sculpture (1.4). All of these figures, of course, are hewn from a large log, which Medellín commemorates with three large logs or branches that serve as dividers between the four registers.

Octavio Medellín, “History of Mexico” (photograph with all four sides), 1950, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, 87 x 18 x 18 in., Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (from exhibition catalog).

If we look again at the image with all four complete sides of the sculpture, we can see that the log/rattlesnake marks off the pre-Hispanic section, terminating in the figure of the Toltec lord.

The second branch goes straight across the middle of the sculpture, marking the conquest from scenes of the revolution. The third branch extends from the second branch on the left (3.1), then it loops upward around the hanged man before diving down (3.3) and then rising up again to become the body of a corn harvester (4.4). The figure of Cortés rhymes with the looping branch above him, as he joins the log/rattlesnake with the second branch. Cortés — as the symbol of the conquest and European domination — is the link between the indigenous world and the revolution.

Diego Rivera, “Mexico Today and Tomorrow,” 1935, fresco, 7.49 x 8.85, South wall of the National Palace staircase, Mexico City. Photograph: Wikipedia.

The compartments Medellín fashioned out of wooden logs or branches gave me a sense of déjà vu. They are reminiscent of the pipes and other materials that form compartments within portions of Mexico Today and Tomorrow (1935), painted by Diego Rivera in the South wall of the National Palace staircase in Mexico City.

A comparison of these two works also points out an essential difference: the nature of Medellín’s divisions (assuming one does not have a composite photograph of all four sides of the sculpture) are only evident when one traces their path by walking around the statue several times. His tree branches are a wooden “thread” that winds its way through the wooden sculpture.

Lewthwaite views the corn harvest scene as symbolic of regeneration and as a suggestion that “Mexican modernity involves a cyclical return to origins in the material and temporal sense, a trajectory in direct contrast to the flow of European history” (p. 355). She believes both Medellín and Rivera view history as “a dialectic between ‘progress and reaction’” (p. 355).

History of Mexico is a very beautiful sculpture, apart from any other considerations. It is also, one the one hand, preternaturally clear. Medellín never loses his narrative logic and rationale. At the same time, History of Mexico is enormously complex in the interrelation of its component parts. These interrelationships proceed vertically as well as horizontally.

The Spirit of the Revolution and History of Mexico are proof that Medellín excelled at utilizing visual symbols in the service of complex storytelling. I only wish that he had made more works like these two sculptures because they demonstrate that he had a very rare talent. His most ambitious works are his greatest achievements.

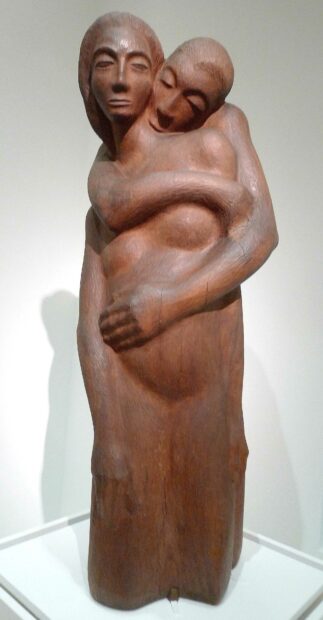

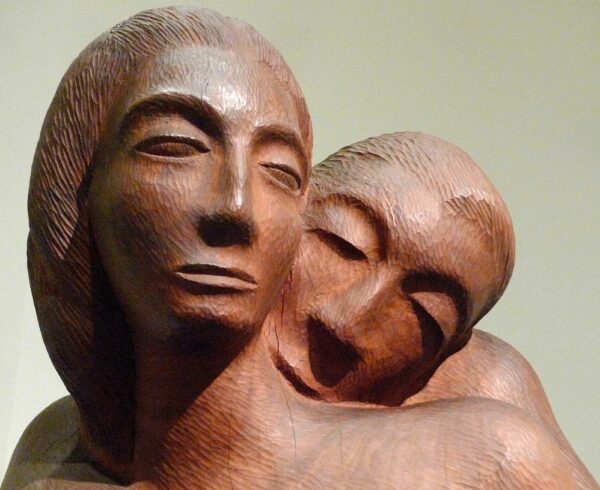

Octavio Medellín, “Conceived” (frontal view), 1950, direct carving in Smoky Mountain wild cherry wood, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in. (120.65 × 50.8 × 40.64 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the work above, man nuzzles the neck of a woman and wraps his arms around her body. From the title, we can conclude that she is pregnant.

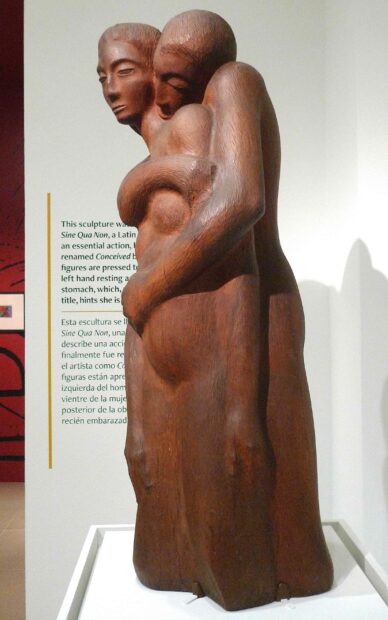

Octavio Medellín, “Conceived” (right view), 1950, direct carving in Smoky Mountain wild cherry wood, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in. (120.65 × 50.8 × 40.64 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

When viewed from the right, the man seems to have the woman wrapped up tight. Judging from the forward tilt of her head, her thoughts could be elsewhere.

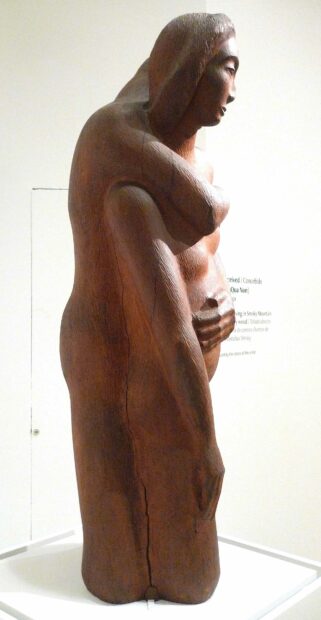

Octavio Medellín, “Conceived” (right view), 1950, direct carving in Smoky Mountain wild cherry wood, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in. (120.65 × 50.8 × 40.64 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The woman’s psychological distance from the man is even more emphatic when viewed from the left. She seems locked in her own world. Castro points out in the catalog that gestures that should be intimate and affectionate appear to be stifling. Moreover, the woman’s arms hang limply at her side. She does not respond to the man’s embrace.

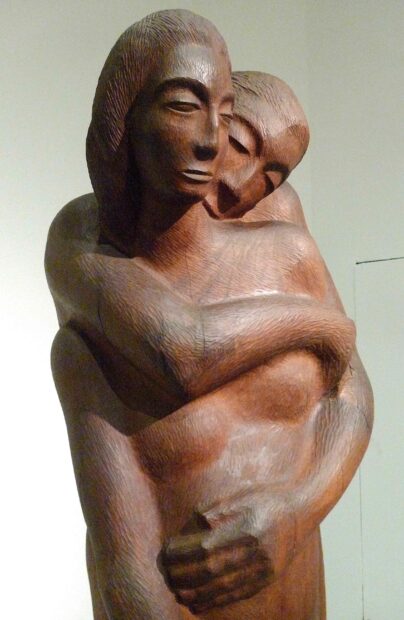

Octavio Medellín, “Conceived” (detail of torso and heads), 1950, direct carving in Smoky Mountain wild cherry wood, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in. (120.65 × 50.8 × 40.64 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Castro notes that her expression is “somber and masklike.”

Octavio Medellín, “Conceived” (detail of heads), 1950, direct carving in Smoky Mountain wild cherry wood, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in. (120.65 × 50.8 × 40.64 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

When viewed in close-up, the man’s head appears rather mask-like as well. Note how the foreheads and noses of the two figures are fused together, like the earliest heads by Medellín treated in Part 1.

Through gesture alone, Medellín conveys differing psychological/physiological perceptions of pregnancy. Whereas the woman perceives her child internally, with no need of the man’s interactions, the man’s only recourse is to grasp and to feel the embryo through the woman’s body.

Of the works carved out of wood in the exhibition, Conceived is the last one that features a rough surface texture. Sculptures in the second half of the show are brought to a highly polished finish. But they are not as good as Genoveva (1949), one of the two earliest highly polished wood statues in the show.

This departure from Medellín’s roughhewn, primitivizing roots resulted in more conventional sculptures. They are less interesting than his earlier sculptures treated in Part 1, or his History of Mexico. Medellín made a concerted effort to break away from his Mexican roots and the bulky, primitivizing style of his earlier works, in favor of more streamlined works with greater degree of abstraction.

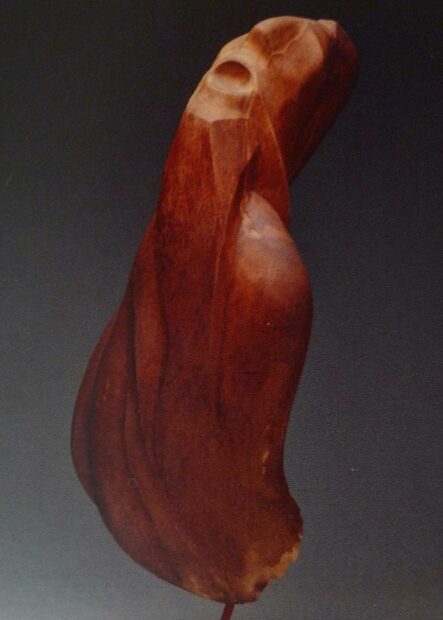

Octavio Medellín, “Fluid Form,” c. 1950, direct carving in wood with metal rebar, 30 3/4 x 14 1/2 x 10 in.; 3/12 x 6 3/4 x 7 in. (base), Scott Chase & Debra Witter. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art (exhibition catalog).

Fluid Form is a flowing mass that terminates in a peak. From one angle, it is clear that the sculpture represents an Old Testament-type figure. This pointy-headed figure has an open mouth and a large nose.

Octavio Medellín, left to right: “Moses,” 1955, direct carving in black walnut with lead fills, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in., lent by the estate of the artist; “The Angel,” 1948, direct carving in black walnut and lead, 60 x 16 x 11 in., collection of George and Beverly Palmer; “Bird in Flight,” 1985, direct carving in black walnut, 65 ½ (without base) x 16 in. diameter, 72 in. high with base, private collection of Brett & Charisse Medellin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Moses (1955), on the left, is a quasi-abstract figure, while the highly polished The Angel (1948), in the center, is as abstract as Medellín ever got. Bird in Flight (1985) likewise has very little figural reference. The Angel won a prize in an exhibition of Texas painting and sculpture that was held at the Dallas Museum of Fine Art (today’s DMA) in 1952. As further proof of its fashionableness, The Angel was long displayed in Neiman Marcus’ flagship store in Dallas. According to Castro, Medellín was at his most abstract in the 1950s, though he also produced figural works during that decade.

Octavio Medellín, “Moses” (detail), 1955, direct carving in black walnut with lead fills, 47 1/2 × 20 × 16 in., lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

One can see Medellín’s continued preference for wood with beautifully patterned grain in the above detail of Moses. He filled the cracks in the wood with lead.

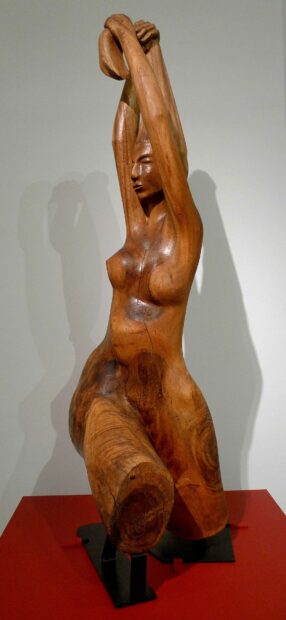

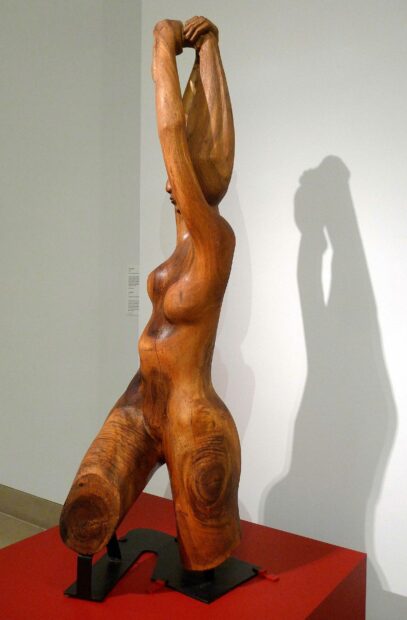

Octavio Medellín, “The Bather,” 1963, direct carving on monkeypod wood, 65 in. high, Sandra S. Simmons. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Judging from what I have seen in reproduction, The Bather is one of Medellín’s best works from the 1960s. Many of his later works are clunky and have not aged well. The Bather has fluid, gently twisting forms.

Octavio Medellín, “The Bather,” 1963, direct carving on monkeypod wood, 65 in. high, Sandra S. Simmons. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

It is interesting from different angles.

Octavio Medellín, “The Bather,” 1963, direct carving on monkeypod wood, 65 in. high, Sandra S. Simmons. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

A close-up reveals the high degree of abstraction in this work.

In his later years, Medellín badly wanted to be recognized as a fine artist and as an “international” artist rather than to be ghettoized as an ethnic or Mexican American artist. He noted that William Zorach was born in Lithuania, but was still regarded as an “American” artist, whereas “every time that it was mentioned about my work it was allwas [sic] Mexican artist” (untitled book manuscript, cited in Lewthwaite, p. 364). In a discussion of modernist universality, Medellín averred: “Art to me has allwas [sic] been that it belongs to no nation but belongs to all people and all of humanity” (Lewthwaite, p. 365).

Medellín’s earlier works developed when there was a great interest in Mexican art in general, and in pre-Columbian sculpture and “primitivist” carving in particular. Medellín’s later ambitions were in keeping with powerful forces that drove post-war tastes in the U.S., which eschewed realism, nationalism, and national schools, and instead favored abstraction as the “universal,” international language of modernism.

In the transformation of Medellín’s sculpture, I am reminded of a statement about individuality and universality made by the sculptor Einar de la Torre, which I utilized in a recent review:

The problem with trying to be universal is that you lose identity. If you try to be like everybody, you actually forget who you are. Because everybody’s gonna like it, that’s just an aesthetic decision of making something pretty. You still need to retain the fact that you came from somewhere and your work has that information of you and where you came from in some way.

Octavio Medellín, “Peacock,” 1985, welded copper tubing with applied brass, 40 x 15 x 22 in., Medellín family. Photograph Ruben C. Cordova.

Peacock serves as an example of a postwar modernist sculpture that is as distant from Medellín’s early work as possible. There is no way one could detect this sculpture’s authorship on the basis of the works illustrated in Part 1 of this review. Medellín has effaced his Mexican roots, heritage, and stylistic origins as a sculptor, and not, in my opinion, to good advantage.

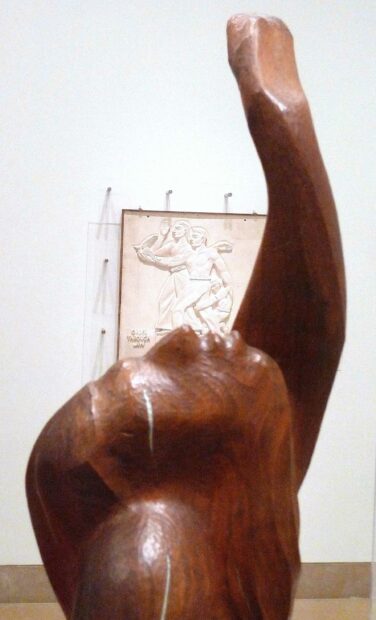

The two works in the background, however, while retaining varying degrees of angular, abstract qualities, bear a clear connection to the sculptor’s earlier work. They are the best of Medellín’s late sculptures. These two sculptures were the only ones Medellín carved with a pneumatic drill. Castro notes that Medellín had been in possession of these two large stones for several years, and the aged artist likely knew they would be among his last works.

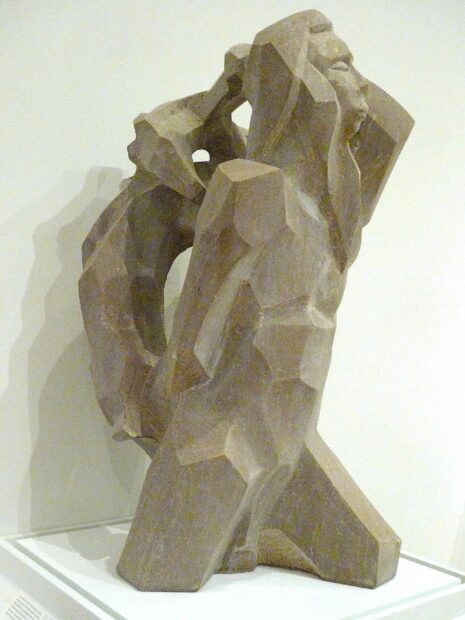

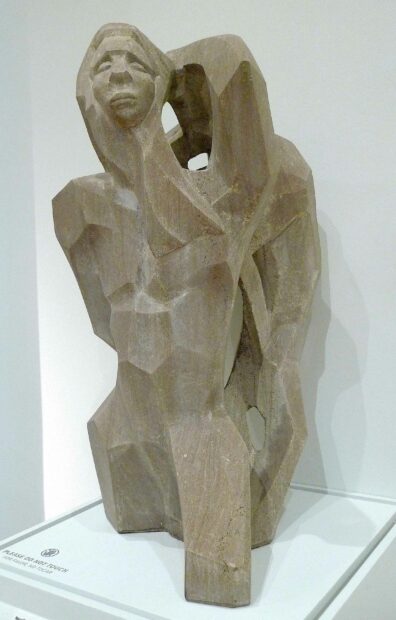

Octavio Medellín, “Mazatlí-Tecutli (Lord Deer)” (viewed from the left), 1995, direct carving in Tennessee marble, 45 x 24 x 20 in., collection of Juli and Sam Stevens. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Mazatlí-Tecutli depicts a legendary chief of the Mazahua, a people who live in central Mexico. When viewed from the left, the great hunter has a diagonal orientation; his dead quarry functions as a counter-balancing buttress. Hunter and hunted are depicted through a pleasing succession of faceted planes.

Octavio Medellín, “Mazatlí-Tecutli (Lord Deer)” (viewed from right of center) 1995, direct carving in Tennessee marble, 45 x 24 x 20 in., collection of Juli and Sam Stevens. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

When viewed from other points of view, such as a little right of center, as in the above photograph, the subject of the sculpture is not intelligible. Perhaps Mazatlí-Tecutli was made to be viewed from the left, almost as if it were a relief. Medellín may not have cared how it looked from other viewpoints. It was not made to be studied in the round, unlike The Penitents, treated in Part 1, which affords the best in-the-round experience of all of Medellín’s sculptures.

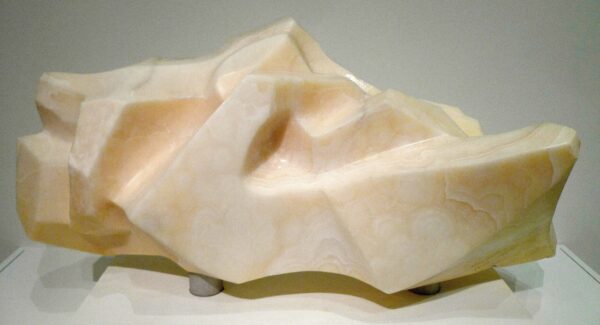

Octavio Medellín, “Mother and Son,” 1995, direct carving in Utah onyx, 23 1/4 x 42 x 13 1/2 inches, collection of Brett & Charisse Medellin.

Mother and Son is both angular and abstract. In my reading of the sculpture, the mother is nursing her child while she is lying down. Her head is the triangular area in the right foreground, likely a reminiscence of the knees of a Chac Mool figure. Her arm is depicted in the center of the sculpture. Above her hand, we can see the head of the child, as well as its arm, which extends down to the waist of the mother. The mother is not holding the child or caressing its head with her left hand because she is using it to facilitate breastfeeding.

Medellín clearly liked the emotion inherent in the parent-child motif. His Mother and Son are related to the Toltec-Maya Chac Mool sculptures he studied in Mexico, as well as to the mother-and-child sculptures by Henry Moore that were themselves influenced by Chac Mool statues. While these reclining Mesoamerican sculptures were receptacles for sacrificial human hearts, Medellín’s Mother and Son is an image of nurture.

Like Mazatlí-Tecutli, Mother and Son has not been brought to a high degree of polish. Medellín clearly wanted the “natural” qualities of the stone to be evident, though this finish required a considerable degree of polishing.

Public Commissions

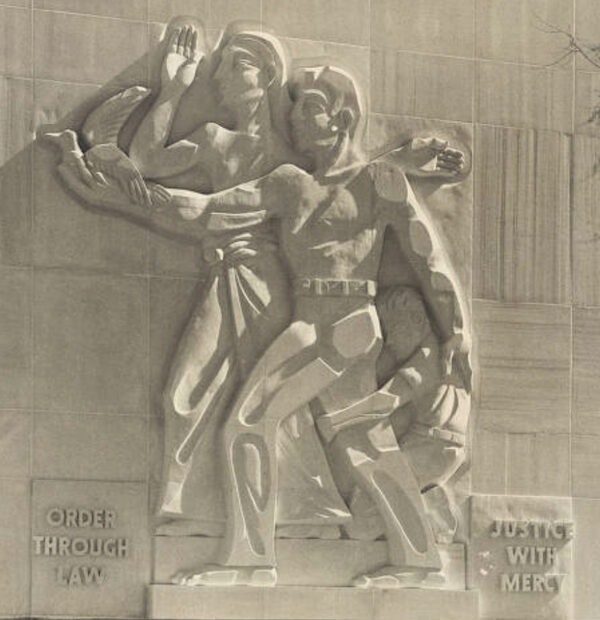

“Photograph of ‘The Family,’” 1948, relief carving in Indiana limestone, 18 x 15 ft., Houston Police Department, Central Patrol Station, Houston, Texas. Photograph: Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

The Family is Medellín’s most interesting public commission. Two heroic semi-nude figures have begun striding forward. The woman holds up her palm in a manner similar to the fear-allying gesture of the Buddha. Her other hand is outstretched dramatically behind the man’s shoulder. The woman’s simple skirt recalls that of the woman in The Spirit of the Revolution (1932-33), discussed in Part 1. As a public commission in Texas, her breasts could not be evident. They are obscured by her husband’s elastically long outstretched right arm, which terminates in a hand that is proffering a dove as a symbol of peace. With his left hand, the man embraces his kneeling son, who has his hands wrapped around his father’s right leg. While the two parents are simultaneously taking initial strides, the child clearly does not want to follow.

The Family has ancient Egyptian-like clarity. It also draws on the pre-war Neoclassical tradition. The latter exuded power and control through monumentality, without a hint of ambiguity. The reluctant child is a really interesting feature. Was he on his knees because he had been punished? Or was he asking for mercy for some malfeasance? In any case, the parents are moving forward, and the boy will be coming with them. This is Medellín’s way of conveying the concept of mercy.

Clearly, Medellín is making a parallel between familial discipline and regulation and social control through law. This is underscored by the Houston Police Department’s motto: “Order through law — justice with mercy,” which is inscribed beside the family trio. The dove must therefore represent the “keeping” of the peace.

Formally, the incision of linear elements in the legs of figures serves to break up their monumentality. In the aftermath of WWII, perhaps this can be understood as a visual way of undercutting images associated with authoritarianism.

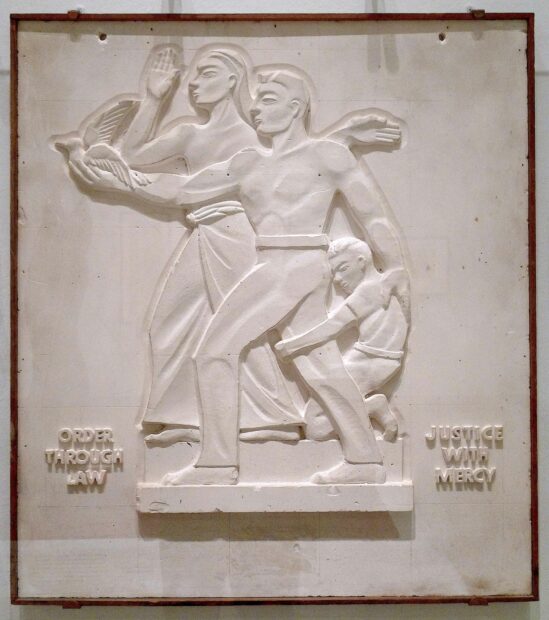

“Maquette for ‘The Family,’” 1948, plaster, 34 ¼ x 30 ½ x ½ inches, Tomas Bustos. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Medellín’s maquette for the police building provides a good sense of the image Medellín carved on the wall, though it has a somewhat more conventional appearance (with only a hint of the incised grooves and the flattened areas on the surface of the relief). Though the man wears shoes in the maquette, he is barefoot in the finished work.

Medellín’s subsequent public commissions are mostly for churches and other religious institutions in Texas, and included mosaics and many stained glass windows. On the limited basis of the studies in the exhibition and the photographs in the exhibition catalog, they appear to be generically deracinated and deculturated. Consequently, they resemble other semi-abstract modernist religious works from the 1950s through the 1970s that could have been made anywhere; as such, they bear no clear connection to Medellín’s earlier work.

I am not saying that art that references Mexican traditions is better than art that does not. Rather, my point is that, in many of his later sculptures and in his later public commissions, Medellín moved away from what he did best. As noted above, this transformation corresponded to a general change in taste, so it facilitated his ability to win commissions. Additionally, Medellín wanted to be regarded as an “American” artist, a universal artist, rather than a Mexican or Mexican American artist. His distaste for and rejection of the term Chicano is discussed below.

Works In Miscellaneous Materials

Octavio Medellín, “Red Horse,” c. 1940, molded and painted plaster, 7 ¼ x 7 ½ x 5 inches, Cortney and Fred Vant Slot. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova

Medellín created many small-scale decorative artworks. In the exhibition catalog Castro notes that they are not well-documented, perhaps because they were made as gifts or because Medellín did not regard them as a central part of his artistic legacy.

The compact forms of Red Horse make it a good example of his ability to make generalized zoomorphic forms. This composition is also known in an example cast in bronze.

Octavio Medellín, “Horse,” c. 1948-1949, Stoneware with smoky celadon glaze, 13 1/2 × 12 1/2 × 7 inches, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase. Photograph: Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

He also made more expressive works, such as this horse with a beautiful glaze, which was exhibited in the First Annual Texas Crafts Exhibition in 1949 at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts. Medellín made a number of ceramic versions of Horse, as well as at least one bronze version.

Octavio Medellín, “Azurmalachite Plate,” c. 1949, glazed stoneware, 3 5/8 × 15 1/4 × 15 1/4 inches. (9.21 × 38.74 × 38.74 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Art Association Purchase, 1949.37

Though documentary evidence indicates that Medellín created pottery “for a significant portion of his career,” this plate is one of the few known examples.

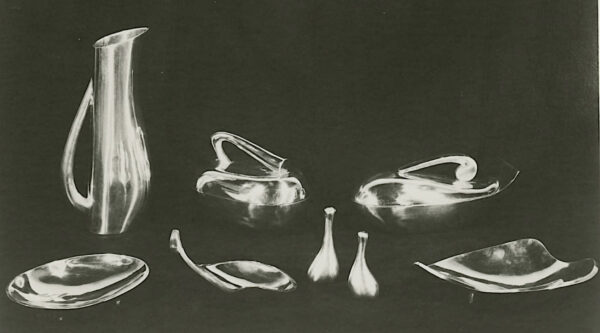

Octavio Medellín, photograph of “Sculptureware by Medellín” Product Line, c. 1974. Photograph: Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

Medellín reworked earlier designs for ceramic dishware into a sandcast aluminum service that he called “Sculptureware by Medellín.” It is a pity that the sleek and anthropomorphic set never went into production. A covered serving dish and a platter — perhaps prototypes for the service because they are less complex and sleek than the examples in the above photograph — were included in the exhibition.

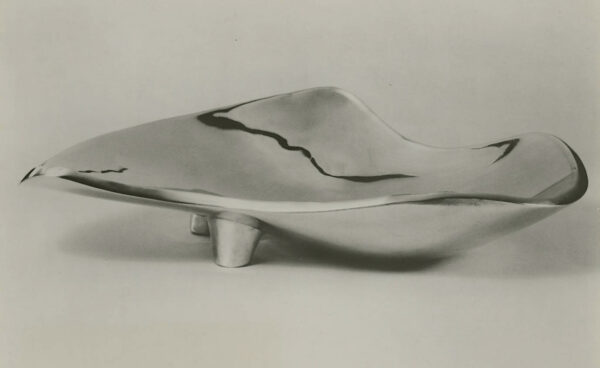

Octavio Medellín, photograph of “Sculptureware Serving Dish” c. 1974, Photograph: Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

In addition to their very artistic designs, Medellín had his dishes photographed in a very artistic manner.

Octavio Medellín, “Ancient Inscription,” 1983, welded copper sheets with applied green patina, 21 ½ x 9 ¼ x 9 ½ inches, collection of Medellin Family. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Ancient Inscription is another late work that I admire. For me, it invokes a giant book writ in three dimensions, with a mysterious, maze-like script that is inscrutably pictographic.

Conclusion

Throughout Medellín’s career, his best work was created in three- dimensional formats, not in painting, printmaking, mosaics, or stained glass windows.

With respect to his status during his early career in Texas, Lewthwaite compares it to Carolina Ponce de León’s characterization of contemporary Chicanos as “double outsiders,” in both the U.S. and Mexico. Lewthwaite argues that Medellín’s

experiences in the art world reflect the broader political, socioeconomic, and cultural marginalization of people of Mexican descent in the United States during the 1930s and 1940s — rejected by Mexico as “too Americanized” (and often condemned as “orphans,” or, worse still, “traitors”) and racialized in the United States as “foreigners” without entitlement to citizenship, regardless of nativity (p. 364).

Lewthwaite (who is concerned with the artist’s work from the 1930s and 1940s) argues that Medellín navigated various crossroads to create a different kind of modernism:

Ultimately, he could neither “return” to Mexico nor claim an essentialist “American” identity in the United States where citizenship was based on whiteness. Medellín’s in-between status positioned him at the crossroads of different art worlds —modernist primitivism, Texas regionalism, and Mexican mestizo modernism — from where he forged an alternative, hybrid, and “cosmopolitan” modernism (p. 370).

The term “cosmopolitan modernism” works for Medellín’s best sculptural period, during which he made powerful hybrid works, especially The Spirit of the Revolution (1932-33), The Penitents (1940), and History of Mexico (1949), but I don’t think it is very applicable to his later work.

Above all, one should note the immense popularity of Mexican art and culture during the late 1920s and the 1930s in the U.S. For a detailed account, see Helen Delpar’s The Enormous Vogue of Things Mexican: Cultural Relations Between the United States and Mexico, 1920-1935 (University of Alabama Press, 1995). Even into the 1940s, Mexican culture wasn’t just mainstream, it was revered. The apotheosis of this fascination was the celebratory survey exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which featured 5,000 artworks.

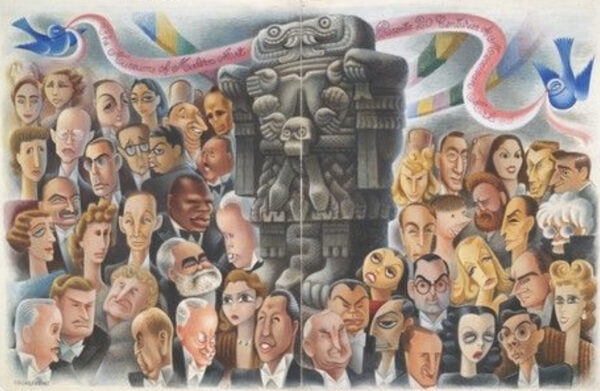

Miguel Covarrubias, “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art at the Museum of Modern Art,” 1940, watercolor, Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Sra. Rose R. de Covarrubias. Illustration published in Vogue magazine. As a wry commentary, Covarrubias has inserted Coatlicue, the most ferocious-looking of the extant Aztec statues (a different version than the one Medellín portrayed in his History of Mexico) into the center of his cartoon. Photograph: Yale University

In the 1930s, primitivism, direct carving, Mexican Muralism and Mexican art in general were important currents of modernism in the U.S. Whereas American (U.S.) art had always been regarded as provincial, Mexican art was exemplary. Mexican Muralism served as the inspiration for W.P.A. art programs during the Great Depression. Until the crisis at Rockefeller Center, leading capitalists competed for Rivera’s services as a muralist.

In sum, Medellín’s early development as an artist in San Antonio was enabled by extremely favorable artistic conditions that were national in scope, rather than merely regional. He picked up a piece of wood in San Antonio and he started carving. He was talented. Equally important, he found help all along the way because he fit into desirable, well-established categories. Doors opened when he approached them, as if by magic. Medellín was not swimming against the artistic tide, he was surfing some of its biggest waves. This eager receptivity helped to shape his work and enabled him to realize his artistic vision. In another age, the level of success he achieved would have been impossible.

Lucy Maverick, Medellín’s most important patron in San Antonio, had participated in archaeological digs in Mexico and Guatemala, and she knew several leading Mexican artists. Her support enabled Medellín to quit his non-art related jobs; she funded a six-month research trip to the Yucatán for Medellín and his family, she supported the gallery at La Villita, she bought his works, she gave him exposure in New York, and she brought him into the orbit of direct carvers and their ideas (Maverick had studied with William Zorach in Provincetown in 1914). Medellín was able to teach at La Villita and the Witte, and, upon his return from the Yucatán, works he exhibited at La Villita caught the eye of Cora Stafford, another Mexican art enthusiast, who offered him a teaching gig (as a sculptor in residence) at North Texas State Teacher’s College in Denton, despite Medellín’s lack of formal credentials (see Part 1).

An entire host of institutions in Texas welcomed Medellín with open arms — precisely because of the vogue for Mexican art and primitivism. Fortunately, they were less uptight about traditional credentials than the academy in Mexico City that turned Medellín away. There was a general feeling that an authentic primitive didn’t need much schooling, and a suspicion that too much formal tuition would only ruin a good primitive artist. Medellín had a charmed early career, marked by numerous opportunities to exhibit, teach, and even to win exhibition prizes. See Part 1, the Appendix below (for Medellín’s one person shows and his teaching experience), and Castro’s exhibition catalog.

After WWII, however, the virulent anti-Communism of the Cold War made Mexican Muralism anathema. Figural art was regarded not only as passé, but as harmfully retrograde. It was the visual language of the arch-enemy, the tool of Communist propaganda. Nationalism was similarly condemned. Abstraction became the new artistic god, as part and parcel of American triumphalism. Abstraction was equated with freedom itself, and with the “American” way, which were posited as equivalents. Under the banner of abstraction, the U.S. claimed the world stage in art, sweeping away its shameful past as a perennial cultural backwater. See Serge Guibaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War (University of Chicago Press, 1984).

Meanwhile, down in Texas, as David Montejano notes, “McCarthyism, in fact, swept Texas with the fervor of a religious revival” in the 1950s (Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986, University of Texas Press, 1987, p. 275). To advocate for unions or desegregation was downright communist. The Red Scare was mapped onto prevailing Jim Crow prejudices.

As noted above, after his History of Mexico, Medellín developed a deracinated and deculturated style, one that reflected his desire to distance himself from politics and from his early Mexican influences. As Medellín floated in this new dominant artistic tide, he probably felt enormous economic pressure to conform to the circumstances brought about by the Cold War era, which prioritized abstraction over figuration, universalism over nationalism, and allegedly neutral subject matter over political art. He wouldn’t be depicting any more spirits of the revolution, nor would he again portray the nationalization of oil as a positive consequence of revolution (the latter subject would likely not have been tolerated by a Texas patron in any time period).

Later, when many Chicano artists were making politically charged works in the early 1970s, Medellín clearly did not want to follow the path they were blazing. He adamantly disliked the term Chicano, and he was very unhappy when he learned, in 1974, that a sculpture of his was reproduced in the anthology We Are Chicanos (see my discussion with Kristel Orta-Puente in the Appendix of this review).

Medellín’s abstraction, especially in his public commissions, had a generic character, one that made it similar to the style of other artists who were working during the postwar period. Sometimes these artworks almost seem interchangeable. This later, rootless style has little connection to Medellín’s great works from the 1930s and 1940s, but it was more consistent with the purportedly universal mid-century modernist taste in the U.S.

From the 1950s onward, Medellín successfully garnered important commissions from religious institutions in Texas, for which, ironically, he created stylistically soulless works. These commissions required studies, maquettes, approval by patrons, and construction within a studio system. Thus they were the exact opposite of direct carving, those philosophical precepts he had professed repeatedly during his early career.

Photograph of Octavio Medellín carving “Mazatlí-Tecutli,” c. 1990-1995, Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, gift of Octavio Medellín.

Near the end of his life, however, when, according to Castro, Medellín was preparing his final artistic testament, he returned to Mexican-rooted themes and stylistic influences in Mazatlí-Tecutli and Mother and Child. Both of these powerful sculptures are the product of direct carving, and they arguably reflect the deepest and truest aspects of his artistic calling.

APPENDIX

Overview of the Medellín Literature

Jacinto Quirarte, Mexican American Artists. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1973.

Quirarte’s pioneering work treats Spanish Colonial, Mexican American, and Chicano art. He spent a day at the artist’s home and studio in 1971. Quirarte’s text on Medellín appears on pages 49-52. He reproduces The Bather (1966, in color), History of Mexico (1949), Uplifting Force (1970-71), and Indian Woman (1931).

Quirarte notes the artist’s connection to Mexico:

Some of the strongest influences have come from Mexico, where he has studied the native and primitive crafts of the Indians who live in the small villages of Veracruz and Yucatán. The directness of their work has had an enduring impact on his sculpture (p. 49).

Quirarte notes that Medellín was denied entrance to the San Carlos Academy in Mexico City because he lacked formal schooling.

Quirarte gives this analysis of Medellín’s History of Mexico:

… comprised of numerous figures represented on all four sides of a seven-foot square column. The figures appear to be literally lunging out beyond the ground or surface that contains them within the confines of the blocklike column. And yet the figures and objects, defined in terms of constantly billowing forms that melt directly into the background as they recede away from the observer, are held firmly in place. Most of the figures are defined in terms of swelling and receding forms instead of contours or outlines, thus the preponderant effect of a constantly changing surface that is always in a state of becoming figure and ground but never quite achieving it…. This creates the effect of a highly charged surface…. Medellín has chosen to deal with the most turbulent aspects of that history: the pre-Columbian world in its most sanguinary aspects, the conquest period, the evangelization process, the revolution, and the post revolutionary period.

… In fact, Medellín has followed in this work pre-Columbian pictorial formats — reliefs and paintings — which are based on horizontal registers.

… The figures and gods in the lowermost register are surprisingly stunted in proportion. They bear the brunt of the impending conquest represented directly above with figures that are twice as large as those seen below (p. 50-52).

Quirarte also praises two of Medellín’s post-History of Mexico works:

There is a sensual quality in Medellín’s works, which is carried by the gently swelling and receding surfaces of The Bather with upraised arms and by Uplifting Force (p. 32).

James Oles, South of the Border: Mexico in the American Imagination, 1917-1947. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

I wrote Part 1 of this review before I was able to consult Oles’ catalog. The quote copied below is from Oles’ discussion of Medellín’s The Spirit of the Revolution, a limestone sculpture dated 1932-33 (for my interpretation of this work, which draws on the letters exchanged between Oles and Medellín housed at SMU, see Part 1):

… shows a kneeling soldier with his gun, sheltered by a taller female figure (fig. 42). Between them, Medellín recalls a shared Precolumbian heritage in the forms of the snakelike Quetzalcoatl, the Central Mexican god of life and wind. In contrast to the smooth forms of the figures, angular bas-reliefs on the rectangular base show birds of peace, a more concise pieta-like image, as well as a stylized scene of actual conflict. The sculpture as a whole might be read as symbolizing the future protected by the past or the peasant watched over by his faith. Medellín himself has characterized the work as “the image of a people in a tragic outcry for freedom from oppression,” caught in a “revolt inflicted by foreign influences and the power of the Christian religion against the forces and spirit of their heritage.” [Medellín’s quote is from the letter to Oles mentioned above.] Medellin’s experience as a direct participant in, rather than a mere observer of, the tragedies of the Revolution allowed him to create a work in which peace and war, hope and despair, are the unresolved elements of recent memory (pp. 73-75).

Stephanie Lewthwaite, “Modernism in the Borderlands: The Life and Art of Octavio Medellín,” Pacific Historical Review: Vol. 81, No. 3 (August 2012), pp. 337-370.

Lewthwaite discusses direct carving and modern primitivism at length in her article. I didn’t read her article until after I had written Part 1 of this review, but I had access to some of her arguments through Castro’s exhibition catalog.

Lewthwaite says that Medellín “synthesized the categories of Mexican art, regionalism, and modernist primitivism to produce an alternative modernism,” one that “reflects the bicultural complexities of becoming Mexican American in the United States — the appropriation and transformation of one’s ancestral heritage while seeking cultural and political citizenship in a new land.” Thus it reveals “the multidirectional and transcultural origins of modernism during the 1930s and 1940s” (p. 337). She specifies Medellín’s multidirectional/transcultural situation: “Medellín’s art was not affiliated only with modernist primitivism but also with Texas regionalism and pan-Americanism” (p. 348). Texas regionalism, she clarifies, was more fluid and expansive than the celebrated but homogenous Midwestern regionalism, since it merged the Old South, the plains, and Hispano-Indigenous traditions.

Lewthwaite offers this interpretation of Spirit of the Revolution:

This sculpture reworks time and narrative, presenting the Revolution as a rerun of Spanish colonial conquest and evangelization, for in both epochs indigenous culture was forced to battle external forces. Spirit establishes a lineage of oppression and violence in the figure of the revolutionary soldier with his gun. Yet it is the presence of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, creator god, and god of wind who presides over the soldier and the series of pre-Columbian-inspired low reliefs along the base that establish the indigenous heritage as a bridge toward liberation and a modern, mestizo future (p. 357).

Kristel Puente, “Chasing Octavio Medellín: San Antonio Artist and Texas Maverick.” Master of Arts in History Thesis, University of Texas at San Antonio, 2021.

This scholar is changing her last name to Orta-Puente, which is how I refer to her in my reviews of the Medellín exhibition. One focus of Orta-Puente’s thesis is the years the artist spent in San Antonio. Castro drew on Orta-Puente’s thesis and he cited it in his exhibition catalog. I benefited from that contribution when I wrote Part I, and I also utilized newspaper clippings that Orta-Puente provided to me.

As noted above, Medellín was angry that his sculpture The Mother was included in We Are Chicanos: An Anthology of Mexican-American Literature (New York, Washington Square Press, 1973), edited by Philip D. Ortega. As she notes in her thesis, Orta-Puente learned this from her uncle, Leopoldo Treviño, who was Medellín’s nephew. Orta-Puente reports that Treviño, who had informed Medellín of his inclusion in the book, was surprised by the degree of the artist’s anger.

Orta-Puente also found a typed letter from Medellín to Quirarte (who was dean of the College of Fine and Applied Arts and a professor of art history at the University of Texas at San Antonio) in the Bywaters Special Collections archive at SMU. In the letter, dated May 9, 1974, Medellín refers to the term Chicano as “a fabricated label by a social and political movement meaning ‘small or smallish.’” (One argument is that the term is a diminutive form of Mexicano.) He does not express anger in the letter, which was professionally typed and clearly edited by someone else, though he registers surprise that his sculpture was reproduced without permission.

In her thesis, Orta-Puente reproduced a section of the letter Quirarte wrote in reply to Medellín:

I understand your concern. As you know from our symposium on Mexican Art, the term “Chicano” is an extremely loaded word. I am very sorry that the more political aspects of the term have been emphasized rather than its meaning in a much broader sense, and that is to designate Americans of Mexican descent who recognized that they are not exclusively Mexican or American in the complete sense of each term, but somewhere in between. As far as I can determine, it is not meant to denigrate anyone in any way. However, many people do find the term offensive. I do not defend its use. That is why I did not use it in the title of my book (Puente, p. 66).

In the above quote, Quirarte refers to the Mexican-American Symposium he organized, which included Medellín as a participant. It was held at UTSA on November 10-11, 1973. At a meeting of the San Antonio-based Chicano art group Con Safo that was held on November 5, several members made strenuous objections to the use of the term Mexican American in connection with the upcoming symposium. Group member Jesse Almazán announced an exhibition mounted in protest against the symposium. He became agitated and insulted some other group members, resulting in a conflict that led several founding members to leave the group. While group members overwhelmingly favored the term Chicano, only some of them wanted to boycott the symposium that Quirarte had organized (Ruben C. Cordova, Con Safo: The Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, 2009, p. 45).

At the symposium, as reported in the San Antonio Light, Mel Casas, the outgoing Con Safo group president, characterized Mexican American as an accommodationist term, in contrast to Chicano, which he termed “a self-imposed and self-determining appellation” (Ibid, p. 45).

José Montoya, a founding member of the Royal Chicano Air Force (a politically committed California-based art group), was also a symposium participant. He gave me this quote:

Con Safo was at the forefront of trying to define Chicano art for those who did not like being hyphenated. I always thought that being called “Mexican-hyphen-American” was like being called “Mexican-hyphen-Gringo” (Ibid, p. 57).

Nomenclature was far more “loaded” than Quirarte realized. Despite his status as a pioneering figure in the field of Chicano art, Quirarte failed to grasp that “Chicano” is a self-designation that is inherently political, not simply a term for in-betweenness. Above all else, it was and is a political term, and to identify as a Chicano is a political declaration. I — and a number of San Antonio-based Chicano artists — had surmised that Quirarte had disapproved of the term Chicano when he wrote his book, but the letter to Medellín is the only admission that I have seen.

I have previously noted that Quirarte angered some Chicano artists by arbitrarily characterizing them as Mexican American (rather than Chicano) artists in a catalog he wrote in 1990 (“Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night: Part 1, The Birth of Chicano Noir,” Glasstire, November 13, 2021).

Orta-Puente is currently in the doctoral program in U.S. history at SMU, where she is researching a dissertation on Medellín. Her focus is biographical: she is particularly interested in identity formation and Medellín’s emergence as an artist in San Antonio and the support systems that enabled him to become a fine artist. Orta-Puente is also trying to trace key works from Medellín’s San Antonio period that were not included in the Dallas Museum of Art retrospective in 2022-23.

On February 19, 2022, Orta-Puente gave a lecture on Medellín at the Dallas Museum of Art. She had this to say about the artist’s Spirit of the Revolution:

… it encompasses both vulnerability and strength in the midst of war. It is not how most western art depicts war and revolution. Note that Medellín often places women in positions of power, strength, and admiration in many of his pieces.

In a conversation with Orta-Puente, she noted that Medellín had a circle of affluent female patrons in Dallas who assisted him with his career. Orta-Puente feels that Medellín probably could not have been outspoken about racism, or about the police killings of Mexican American youth in Dallas as documented in the book White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001 (2006) by Michael Phillips. We both suspect that Medellín’s eschewal of politics was at least partially grounded in economic necessity.

In her lecture, Orta-Puente says Medellín’s The Hanged One

… alludes to the violence he witnessed as a young boy during the Mexican Civil War, but also has undeniable connections with scenes of the lynching of Black and Brown men in the United States. According to the book Forgotten Dead by William D. Carrigan and Clive Web, between 1848-1928, Texas had more than half of incidents of mob violence against Mexicans, with 232 out of 547 cases, many of them classified as lynchings. Furthermore, 1910-1920 was one of the most violent decades, with an estimate of incidences of mob violence being about 107. … Mexicans in the borderlands were aware of the violence. A local paper in San Antonio at one point stopped reporting on lynchings due to the frequency of their occurrence. Medellín did something extraordinary here, he contextualized the pain he had seen and felt and placed that in the work he created, instead of harboring it in his soul. He had experienced much pain and displacement as a young boy and crafted that into a visual element that became universally recognizable. It was one of his gifts.

Orta-Puente also praised Medellín in her lecture for the lives he touched as a teacher:

The real measure of an extraordinary force is how many people’s lives they touched. Medellin taught thousands of students in his 70 year career. The most important thing is not that he might have ever taught any ONE famous student in the art world, it is that he taught hundreds and maybe thousands of people like you and me, ordinary folks longing to create something beautiful in the world. There are countless stories about his kindness and generosity as a teacher. Starting an art school is not a small thing, especially one that is still operational today. He may have claimed to not be political, or an activist but what he did accomplish was a radical revolutionary act, making art accessible to everyone.

Mark A. Castro, Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form. Dallas Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022.

This excellent catalog provides an overview of Medellín’s career. It also discusses individual works in the last section. This was my primary resource for both parts of my review, and I mentioned it many times. Anyone interested in Medellín should read this catalog.

Medellín’s Solo Exhibitions

1938: The Witte Memorial Museum, San Antonio.

1939: North Texas State Teacher’s College Library [now University of North Texas], Denton.

Dallas Museum of Fine Arts.

The Witte Memorial Museum, San Antonio.

1940: Wesleyan College [now Texas Wesleyan University], Fort Worth.

North Texas State Teacher’s College Library [now University of North Texas], Denton.

1941: North Texas State Teacher’s College Library [now University of North Texas], Denton.

1942: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts.

Harris and Company, Dallas.

Fort Worth Public Library.

1945: Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

1947: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts.

1965: First Methodist Church, Dallas.

Saint Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church.

1996: Dallas Visual Arts Center.

2016: Latino Cultural Center, Dallas.

2022-23: Dallas Museum of Art.

Medellín’s Art in Public Collections

Dallas Love Field Airport.

Dallas Museum of Art.

Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, Missouri.

San Antonio Museum of Art.

Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University.

The University Art Collection, Southern Methodist University.

Syracuse University Library, Syracuse, New York.

Witte Museum, San Antonio.

Medellín’s Teaching Positions in Texas

Witte Museum of Art and La Villita Art Gallery, 1934-37.

Sculptor in Residence, North Texas State Teacher’s College [now University of North Texas], Denton 1938-42.

Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and Southern Methodist University, 1945-66.

Operated Medellín School of Sculpture, Dallas, 1966-79.

Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form was curated by Mark A. Castro and was on view at the Dallas Museum of Art from February 6, 2022 – January 15, 2023.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than 30 exhibitions and who has written or contributed to numerous catalogs and books, including The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth and The Day of the Dead in Art. In addition to Medellín Part 1, he has previously reviewed two exhibitions at the DMA for Glasstire: “To Renew the World: Spirit Lodge and the Looting of the ‘King Tut’s Tomb’ of Oklahoma,” and “Van Gogh’s Symbolic Olive Trees and Landscapes at the Dallas Museum of Art.”