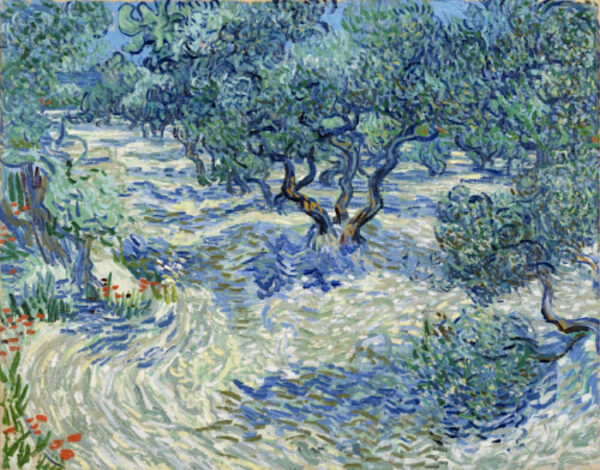

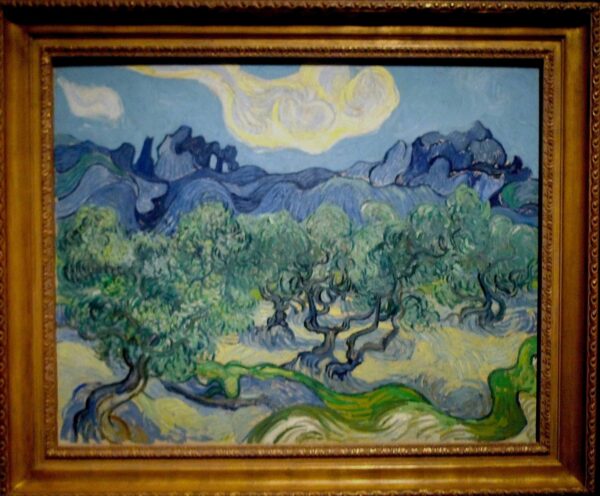

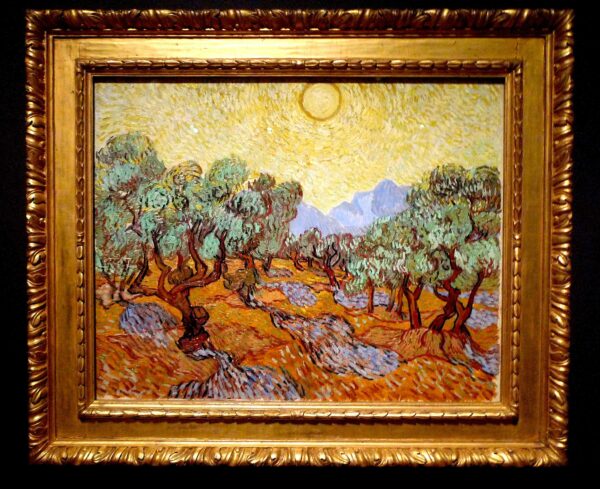

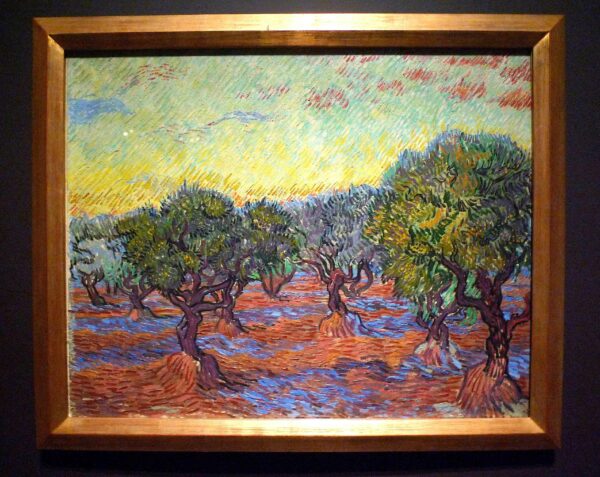

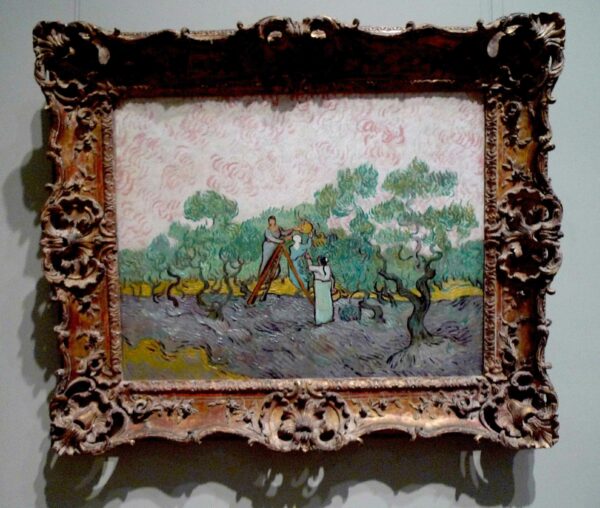

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Trees,” June 1889, oil on canvas, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-2. Image courtesy of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Media Services/Photo: Gabe Hopkin. Van Gogh and the Olive Groves had its origin nine years ago, when co-curator Nicole R. Myers began studying this painting while working as a curator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

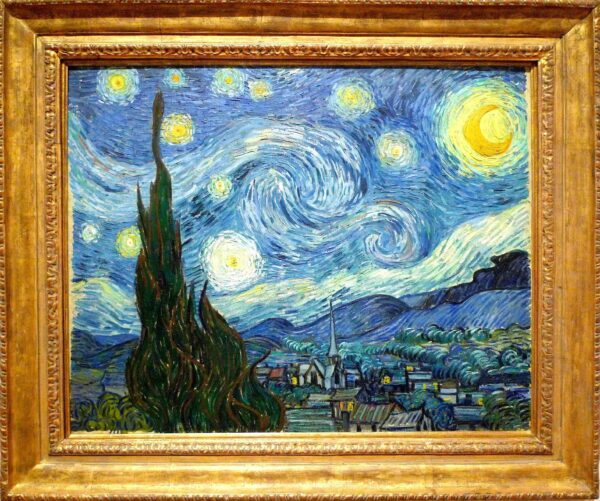

In addition to his status as one of the greatest of modern painters, Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) was also a remarkable letter writer who provided vital insights into his work, beliefs, and aspirations. In a letter to his brother Theo on or around September 29, 1888, van Gogh declared: “That doesn’t stop me having a tremendous need for, shall I say the word — for religion — so I go outside at night to paint the stars…” (Quotes from van Gogh’s correspondence are from Vincent van Gogh: The Letters.)

While van Gogh’s starry night skies are widely revered as pantheistic celebrations of the natural world, a ground-breaking exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) titled Van Gogh and the Olive Groves provides an opportunity to consider how olive trees could also have served a similar purpose. The exhibition, which is the product of a long and fruitful collaboration between the DMA the Van Gogh Museum (VGM) in Amsterdam, is a triumph of scholarship and presentation.

Vincent van Gogh, “The Starry Night,” June 1889, oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. (Painting not in the DMA’s exhibition.)

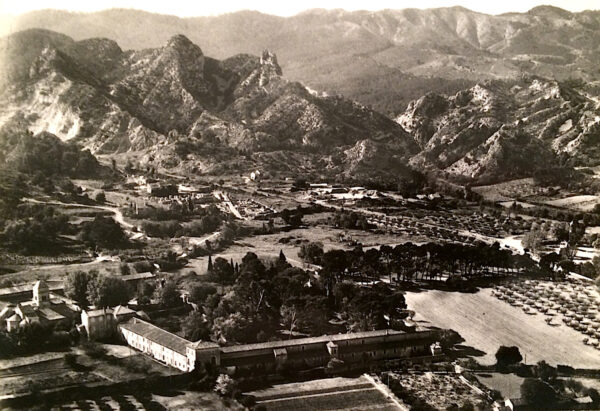

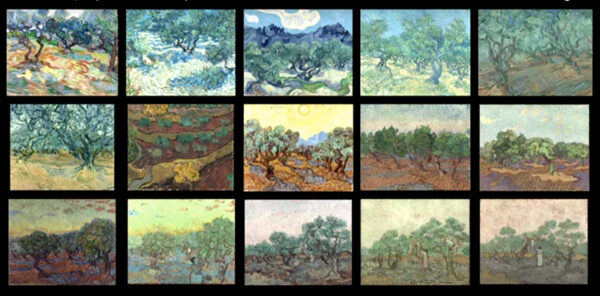

As wondrous objects of reverence and veneration similarly laden with symbolic significance, the olive tree paintings were — like van Gogh’s starry skies — meant to provide solace and comfort, essentially serving as substitutes for conventional Christian content. Ten of the fifteen olive tree paintings that comprise this series are in the DMA exhibition, as well as twelve additional paintings by van Gogh that were made before, concurrently, or after the olive grove series. The entire group of olive grove paintings was made between June and December of 1889 (punctuated by an incapacitating six-week mental breakdown), while van Gogh was a self-committed patient at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, in the South of France.

In a letter to Theo from Arles dated June 5, 1888, van Gogh noted that progressive artists loved Japanese art. He also referred to the South of France as “the equivalent of Japan.” Whereas the Impressionists prioritized empirical observation as a means of breaking with long-standing conventions, the artists we now refer to as the Post-Impressionists sought to render and accentuate sensations in a more personal, arbitrary, and expressive manner. In the letter cited directly above, van Gogh stated that the experience of the South endowed his work with a Japanese character:

… after some time your vision changes, you see with a more Japanese eye, you feel colour differently. I’m also convinced that it’s precisely through a long stay here that I’ll bring out my personality. The Japanese draws quickly, very quickly, like a flash of lightning, because his nerves are finer, his feeling simpler.

Speed of execution became one of van Gogh’s hallmarks. He often completed paintings in a single session. For short videos that demonstrate how Japanese art — especially woodblock prints — influenced van Gogh’s style, see the Van Gogh Museum’s What did Van Gogh learn from Japanese prints? and The Canvas’ How Japan Influenced Van Gogh, Impressionists and Modern European Art.

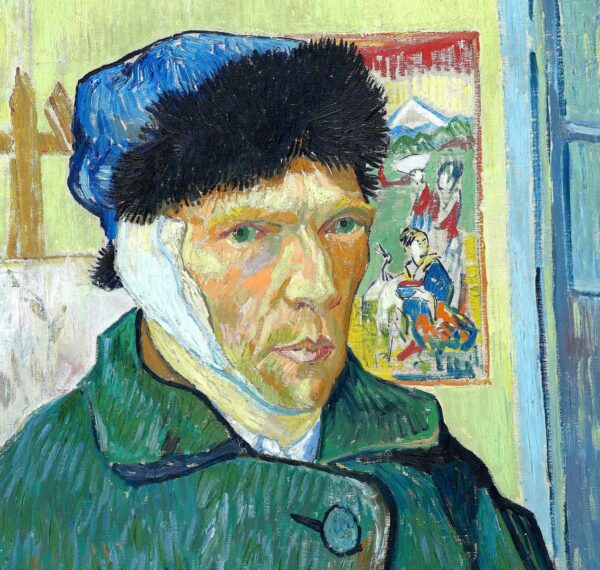

Vincent van Gogh, “Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear” (detail), June 1889, oil on canvas, Courtauld Institute, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. (Painting not in the DMA’s exhibition.)

From February 1888 to May of 1889, when van Gogh moved to Saint-Rémy, the artist had worked in nearby Arles, where he produced his most important body of work. Van Gogh attempted to found an art colony in Arles. After much cajoling, he persuaded Paul Gauguin to join him in October of 1888. Gauguin consented because he was broke; Theo financed his trip (see Douglas W. Druick, et al., Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South, 2001).

After an intense quarrel with Gauguin, when it was clear that his dream of an artist’s commune would not be realized, van Gogh cut off his left ear (except for a small part of his lobe) on December 23. This episode coincided with van Gogh’s first mental breakdown. Martin Bailey theorizes that the self-mutilation was an attempt to silence severe auditory hallucinations. (See Sarah Cascone’s discussion of Bailey’s 2018 book Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum in Artnet News.)

Van Gogh gave his excised ear to a young woman named Gaby and told her: “keep this object carefully,” which caused her to faint. Gaby cleaned a local brothel patronized by both Gauguin and van Gogh (the prostitutes and women in general preferred Gauguin). After many years of research, Bernadette Murphy discovered Gaby Berlatier’s real name (she was previously identified as Rachel) and established that — contrary to general belief — Gaby was not a prostitute. She also worked at the Café de la Gare, which van Gogh patronized; he also rented a room there from May to September of 1888. (Virgie Hoban discusses Murphy’s research in “What Actually Happened to Vincent van Gogh’s Ear?” Berkeley Library News, November 26, 2019.)

Gaby went to Paris for 18 days of treatment at the Institut Pasteur after a rabid dog bit her in Arles on January 8, 1888. Van Gogh mentioned “the citizens who live at the Institut Pasteur” in a letter to Theo on July 9 or 10, 1888. A 2017 BBC film, The Mystery of Van Gogh’s Ear, traces Murphy’s research. In that film, she speculates that van Gogh might have met Gaby in Paris and followed her to Arles.

The symbolic significance of van Gogh’s act of gifting the ear was explained by Albert J. Lubin in his book Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh (1972). He wrote that — in Arles, where van Gogh attended a bullfight on April 8, 1888 — a matador could be rewarded with an ear from the slain bull as a prize. On a symbolic level, this would make van Gogh both victorious matador and vanquished bull. But the BBC film says this practice was a later import from Spain. According to Murphey’s book Van Gogh’s Ear (2016), the first bullfight in which a bull was killed in Arles took place in 1894, though van Gogh could have heard of the practice without observing it himself. In any case, the bullfight van Gogh described to Theo was not completed due to injury. Van Gogh informed Theo: “A toreador crushed one of his balls jumping over the barrier.”

The Mystery of Van Gogh’s Ear ends with a religious explanation. Murphy characterizes Gaby as “one of the wounded angels he [van Gogh] wanted to help.” The narrator draws this conclusion: “Vincent had always been drawn to unfortunate women and nurtured Christ-like fantasies of martyring himself for the poor. It looks as if in his distress he saw giving Gaby his ear as an act of religious self-sacrifice and compassion.”

Now, to relate ears to the olive groves, recall that, according to the Bible, Christ was captured in the garden of olives prior to his trial and execution. In an attempt to prevent his capture, Simon Peter struck Malchus (the servant of the Jewish High Priest Caiaphas), cutting off his ear, which Christ miraculously restored. For van Gogh, the ear seems to have been some kind of sacrificial totem (whether bullfight-related or not) endowed with magical properties. Perhaps — in his confused state — van Gogh thought that by gifting the ear he could miraculously restore it to his own head.

Ironically, it was Irving Stone, author of the sensationalizing biographical novel Lust for Life (1934), who secured the single most important piece of evidence pertaining to the ear incident. He asked Dr. Félix Rey, the doctor who attended to van Gogh in Arles, to comment on the case. Rey replied with a before/and after drawing of the ear, which included the statement: “the ear was cut by a razor following the dotted line.” (The discovery of this evidence should put to rest the recent theory that Gauguin cut off van Gogh’s ear with his sword.) Van Gogh had almost nothing to say about the incident. In a letter to Theo on December 30, 1888, Dr. Rey said the artist referred to it as “a purely personal matter.” Dr. Peyron, who attended van Gogh at the asylum at Saint-Rémy, made the following note on May 8, 1889: “he has no more than a vague memory of all that, and is not aware of it” (see the comprehensive discussion of the ear incident in vangoghletters.org).

We should also note that Christmas was a fraught time of year for van Gogh. Isabella H. Perry has noted a number of “major catastrophes” suffered by the artist during the Christmas season, beginning in 1874 (“Vincent van Gogh’s Illness: A Case Record,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, March-April 1947). The fact that he often did something bizarre or self-destructive at this time of year points to van Gogh’s uneasiness with organized religion as he had experienced it. He would have another disastrous breakdown in December at Saint-Rémy, which would lead him to depart the asylum once he had recovered.

Van Gogh did not feel confident to live alone after suffering multiple mental breakdowns. Moreover, he was harassed by some of the locals in Arles. A petition to have him institutionalized was circulated in February of 1889. It might have been the handiwork of the manager of the house van Gogh rented — which he immortalized in his paintings as the Yellow House — because, as Murphy has demonstrated, 24 of the 30 people who signed the petition were acquaintances of the manager who were not from Arles. In Van Gogh’s Ear, Murphey notes that the manager had already made an agreement to rent out van Gogh’s quarters to a tobacconist.

Photograph of the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole with the Alpilles mountains in the background, postcard, c. 1940s. Photo: Van Gogh Route. Originally an Augustinian monastery with impressive Romanesque architecture, the asylum was run by the Catholic Sisters of the Order of Saint Joseph.

In the agriculturally developed countryside around Arles, van Gogh painted motifs such as wheat fields and blossoming fruit orchards. The latter related directly to the blossoming trees in the Japanese prints that van Gogh collected and admired. In the more forbidding environs of Saint-Rémy, which was less developed, with poor soil that was sandy and rocky, van Gogh painted the resilient olive trees that were its chief crop. The olive grove pictures represent 10% of the 150 paintings van Gogh completed during the year he spent at the asylum in Saint-Rémy.

Thumbnail images of all 15 paintings in the series. Photo: screen shot from “Conservation Spotlight: Vincent Van Gogh, 2021.” These paintings are arranged chronologically commencing in the upper left.

Before Van Gogh and the Olive Groves, there had never been an exhibition or a serious study that focused exclusively on this series. Van Gogh made so many remarkable paintings that this body of work has usually flown under the art historical radar. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art essay on van Gogh, the olive groves are only mentioned once, even though the museum owns two paintings in the series. John Walsh, in his 2019 lecture Van Gogh and the Asylum at Saint-Rémy, includes three olive grove paintings.

Wide-angle installation shot of DMA gallery with ten olive grove paintings and one large drawing by van Gogh. The paintings are ordered chronologically, starting from the near right, proceeding in a counter-clockwise manner. Photo: John Smith, courtesy of the DMA.

The blockbuster exhibition Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers that Ronald Pickvance organized at the Metropolitan in 1986 (the catalogue can be downloaded here), was exceptional in the attention he gave to the olive grove paintings. Pickvance included no less than seven olive grove paintings in his show. They correspond to the seven largest paintings (on size 30 canvases) in the DMA exhibition. They are situated on the two side walls in the installation shot reproduced above.

In 1993, Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński published an excellent and comprehensive article called “Vincent van Gogh’s Paintings of Olive Trees and Cypresses from St.-Rémy” in the Art Bulletin. I did not come across it until this article was almost finished, but if I write again on this subject I will explore some of the issues raised in the article and its bibliography.

Installation shot of the DMA gallery with three olive grove paintings and one large drawing by van Gogh. They are arranged chronologically from right to left. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the installation shot above, one can see the Nelson-Atkins painting (also reproduced at the beginning of this article); the painting at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), whose abstracted, visionary aspects most closely approach The Starry Night; and the signed painting in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo.

Installation shot of the DMA gallery with four olive grove paintings by van Gogh. They are arranged chronologically from right to left. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Starting on the right, one can see: the painting with the sun in Minneapolis; the painting at the VGM with the pink sky; the colorful painting at Gottenburg; and The Olive Pickers in Otterlo. (According to the DMA/VGM curatorial team, the paintings on these two walls are the second, third, fourth, eighth, ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth paintings in the series.) These seven olive tree paintings did not register very strongly with most visitors at the Metropolitan’s 1986 Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers exhibition, who crowded around other works. In that show, the olive tree paintings faced dazzling competition from The Starry Night, Blossoming Almond Branches, and Entrance to the Mine, as well as paintings of cypresses, irises, and great portraits that Van Gogh also painted at Saint-Rémy (in addition to the pictures he subsequently painted in Auvers).

In the dark chamber of the oval — or olive — shaped second gallery, which is painted a striking aubergine (the purple-with-a-hint-of-brown color of a dark eggplant), van Gogh’s ten olive grove paintings take center stage, where they shimmer like jewels. I don’t think that anyone who sees this exhibition will forget these paintings. Ironically, the purple colors that van Gogh mixed into these canvases are precisely the ones that have faded the most, so the walls are emblazoned with that now-missing color. Nicole R. Myers, the DMA’s Barbara Thomas Lemmon Senior Curator of European Art, organized the exhibition at the DMA. She explained to me that the low-light level was necessitated by lender agreements due to the fragility of some of van Gogh’s pigments, including chrome yellows. Myers adds that visitors “gasp in delight” upon entering the chapel-like setting of the second gallery (it is much darker than it appears in the photos).

While I do not consider the olive grove pictures to be the equal of the best work Van Gogh produced at Saint-Rémy, they are fine paintings, nonetheless. The quality of the work from the last two years of van Gogh’s life is astonishing, as is the speed with which he painted these pictures. I enthusiastically recommend this exhibition to anyone who appreciates art. I have had many opportunities to see van Gogh’s olive tree paintings, beginning in 1978, when I traveled extensively and wrote my first art history final paper. It treated The Starry Night and the olive grove painting now at MoMA, and I discussed many of the letters quoted in this article. (Despite my enthusiasm, I had no idea what I was doing, and I am grateful to have the opportunity to write about this material again.) I imagined how this exhibition would look, but nothing prepared me for the artistry with which these paintings are presented in Van Gogh and the Olive Groves. I have never seen his work presented in a more beautiful and dramatic fashion.

It has been extremely difficult to mount van Gogh exhibitions for many decades. Negotiations for some of the pictures lent to Van Gogh and the Olive Groves took up to five years. Even back in 1984, when Pickvance mounted his Van Gogh in Arles exhibition at the Metropolitan, he was unable to secure many important loans. That exhibition, for instance, lacked any of the canonical paintings of sunflowers in vases. Pickvance also had trouble securing loans for his Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers exhibition. As the monetary value of van Gogh’s paintings continues to escalate, it becomes ever harder to borrow them. Therefore it is quite an accomplishment to have gathered a total of 22 van Gogh paintings and a large drawing for this exhibition, as well as an important Gauguin painting and an accompanying illustrated letter. Unfortunately, due to a prior commitment and an exhibition calendar affected by the COVID pandemic, one of the two van Gogh paintings owned by the DMA could not be in the exhibition. Sheaves of Wheat was painted in Auvers in July of 1890 and was likely one of the artist’s last paintings.

Photograph of the exhibition research team at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: screen shot from “Conservation Spotlight: Vincent Van Gogh, 2021.” The full research team convened in Holland in the fall of 2018, and reunited at the Metropolitan in the fall of 2019.

The two olive grove paintings owned by the Metropolitan are on easels for closer inspection. The one on the left features the most Divisionist brushwork in the entire series. It can be accessed on the Met’s website here.

The picture on the right is the last of three versions of “Women Picking Olives,” and is discussed below. Both paintings came to the Metropolitan with the Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg collection, and they cannot be lent. (The second version of “Women Picking Olives” was gifted to the National Gallery in Washington D.C. by Chester Dale with the same prohibition.) The Metropolitan also owned the first version of “Women Picking Olives” (also discussed below) until it was sold by director Thomas Hoving in 1972 (see my Glasstire article: “Deaccessioning at the Met: From Scandal to Plein-Air Bonanza to Collection ‘Care,’” which also briefly discusses the Annenberg collection)

One of Van Gogh’s paintings of now-faded pink roses (discussed below), which is also in the Annenberg collection, is visible in the far right of this photograph.

In 2012, When Myers was an associate curator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, she commenced research on the museum’s olive grove picture (illustrated at the top of this article). As Myers notes in a DMA blog, she was “shocked to find that the painting belonged to a significant series about which I knew nothing.” Myers also discovered that there were many uncertainties and unanswered questions about this body of work.

Myers told me the thought of an exhibition came quickly to her. Within two or three years, she approached the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Since it owned three of the fifteen paintings in the series, as well as the two relevant drawings, Myers reasoned that an exhibition would not be possible without the VGM’s participation. She was delighted by the VGM’s positive reception of her proposal. The partnership became official in 2015.

As Myers notes in the DMA’s blog, her inquiries “launched the exhibition and the unprecedented comparative study that involved an international team of curators, researchers, conservators, and scientists.” When Myers came to the DMA in 2016, she brought the exhibition concept with her. After the show closes at the DMA on February 6, it will travel to the VGM in Amsterdam.

Nienke Bakker, Senior Curator of Paintings at the VGM, co-curated the exhibition with Myers. The collaborative partnership between the two museums included conservation and scientific research led by Kathrin Pilz, Paintings Conservator at the Van Gogh Museum. Research on the 15 paintings resulted in discoveries pertaining to Van Gogh’s techniques and materials. This allowed the team to draw new conclusions about the chronology of the series, as well as how paintings done in the studio differed from those executed outside, en plein-air. (For a discussion of plein-air painting, see my Glasstire article “Deaccessioning at the Met: From Scandal to Plein-Air Bonanza to Collection ‘Care’”).

The exhibition team also drew conclusions about how the fugitive nature of some of van Gogh’s pigments affected paintings in the exhibition. In a joint statement, co-curators Myers and Bakker declared: “After years of research, we are thrilled to reunite the olive grove series for the first time… These fascinating paintings clearly held an important place for Van Gogh within his oeuvre.” As noted above, three paintings in the series are prohibited from traveling, due to the terms by which they were gifted to the Met and the National Gallery. The VGM will display eleven olive grove paintings, but not the one from MoMA.

Introduction to the Exhibition: Series and Ensembles

The introductory gallery of the exhibition features four small van Gogh paintings. Van Gogh tried — unsuccessfully — to market the first two paintings in the installation shot pictured above as components of a triptych that represented Spring.

Under the deep influence of Jean-François Millet’s (1813-1875) paintings of laboring peasants, van Gogh was very attentive to the seasons and to the symbolism of sowing and reaping. As the son of a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church and as a failed lay minister in the poor, coal-mining region of the Borinage in Belgium (where he was charitable to a fault and dismissed for excessive zeal and “undermining the dignity of the ministry”), van Gogh had a deep knowledge of Christian literature and symbolism. He identified deeply with peasants and the working poor. Nonetheless, he avoided painting his own compositions of biblical stories.

In Arles — immediately preceding his Saint-Rémy period — van Gogh stated that he wanted to avoid explicitly religious subject matter (his letters are quoted below). He sought to endow images of the natural world with the same emotional power as religious subjects.

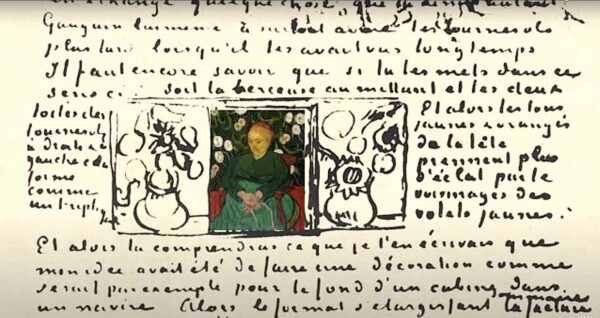

Detail of January 28, 1889 letter to Theo, with sketch of triptych (with photograph of La Berceuse (a painted portrait superimposed) over his sketch). Photo: screen shot from Van Gogh: Irises and Roses, 2015.

In a letter to Theo from Arles on January 28, 1889, van Gogh wrote of making multiple “soothing” triptychs composed of a portrait called La Berceuse framed on both sides by sunflower paintings. Van Gogh wrote of “Icelandic fishermen and their melancholy isolation, exposed to all the dangers, alone on the sad sea.” Van Gogh explained that he viewed sailors as “children and martyrs,” and he imagined the portraits would provide them with the “feeling of being rocked, reminding them of their own lullabies.” Van Gogh elaborated that the sunflowers would “thus form standard lamps or candelabra at the sides.” La Berceuse was essentially a comforting secular Madonna. She was meant to be “illuminated” by candelabra-like paintings of sunflowers in a structure that invoked an altarpiece, one custom-made to soothe the children/martyrs of the sad sea.

Van Gogh, in fact, wanted to replace conventional religion and religious subjects, as he noted in a letter to Theo written in Arles on September 3, 1888:

Ah, my dear brother, sometimes I know so clearly what I want. In life and in painting too, I can easily do without the dear Lord, but I can’t, suffering as I do, do without something greater than myself, which is my life, the power to create. And if frustrated in this power physically, we try to create thoughts instead of children; in that way, we’re part of humanity all the same. And in a painting I’d like to say something consoling, like a piece of music. I’d like to paint men or women with that je ne sais quoi of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colorations.

In the same letter, van Gogh explains how he wants to convey love, consciousness, hope, and ardor through color itself in depictions of the natural world:

To express the love of two lovers through a marriage of two complementary colours, their mixture and their contrasts, the mysterious vibrations of adjacent tones. To express the thought of a forehead through the radiance of a light tone on a dark background. To express hope through some star. The ardour of a living being through the rays of a setting sun. That’s certainly not trompe-l’oeil realism, but isn’t it something that really exists?

Van Gogh’s discomfort with religious imagery came to a dramatic head when he twice attempted — and twice destroyed — a painting of Christ in the garden of olives. He wrote to Theo from Arles on July 8 or 9, 1888:

I’ve scraped off one of the large painted studies. A Garden of Olives — with a blue and orange Christ figure, a yellow angel — a piece of red earth, green and blue hills. Olive trees with purple and crimson trunks, with grey green and blue foliage. Sky lemon yellow.

I scraped it off because I tell myself it’s wrong to do figures of that importance without a model.

In a letter to Theo dated September 21, 1888, van Gogh explained the destruction of his second painting of Christ in the garden of olives:

For the second time I’ve scraped off a study of a Christ with the angel in the Garden of Olives. Because here I see real olive trees.

But I can’t, or rather, I don’t wish, to paint it without models. But I have it in my mind with colour — the starry night, the figure of Christ blue, the strongest blues, and the angel broken lemon yellow.

And all the purples from a blood-red purple to ash in the landscape.

Van Gogh also reported the destruction of the second version of this theme to Émile Bernard around October 5, 1888:

I mercilessly destroyed an important canvas — a Christ with the angel in Gethsemane — as well as another one depicting the poet with a starry sky — because the form hadn’t been studied from the model beforehand, necessary in such cases — despite the fact that the colour was right.

As we shall see, Van Gogh subsequently criticized Gauguin’s and Bernard’s versions of Christ in the garden (the letter to Gauguin is lost; the one to Bernard is harsh). Did van Gogh seek to express something equivalent in power and pathos to Christ’s passion in his subsequent paintings, with only the olive trees themselves, in their gnarled, twisted forms, their “complementary colors,” and their “mysterious vibrations of adjacent tones”?

Van Gogh’s anxiety extended to relative abstraction. He recoiled from the imagined, exaggerated features of The Starry Night and its closest cognate in the suite of olive grove paintings. Van Gogh instead tacked closer to nature—as if his sanity depended upon it.

The Olive Grove Paintings: June and July

The full parameters of van Gogh’s investigations are evident in the first three paintings in the series. The first painting, on the right, is a freely painted sketch, done before the motif. The second (reproduced in full at the top of this article) is one of the most highly resolved depictions of trees, shadows, and earth. The third painting is van Gogh’s greatest olive tree flight-of-fancy.

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Trees” (detail), June 1889, oil on canvas, National Galleries of Scotland. Purchased 1934. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

This painting follows an exploratory brush and ink sketch in the VGM. The exhibition team concluded that this painting was done out of doors in a single sitting. Van Gogh painted with great rapidity and confidence, applying a myriad of colors in discrete and varied strokes. Sometimes he used straight, parallel strokes, as in his treatment of the ground. In his handling of the olive tree leaves, van Gogh utilized curving, overlapping strokes of variable length. The green foliage just above the horizon line is rendered in a flat, generalized manner. The lightest areas at the top of the detail are rendered in thick impasto. A zoomable image on the National Galleries of Scotland website can be viewed here.

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Trees” (detail), June 1889, oil on canvas, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The Nelson-Atkins picture is a gem of a painting that, at first glance, looks relatively straightforward. That is, until one takes a good look at the ground: it shimmers like quicksand and seems to flow like an ocean current. In the far right of the detail reproduced above, a round treetop emanating from a single branch seems to be reflected in the earth beneath it, as if the ground were a perfect mirror. That leafy-green mirror image then merges with blue areas of shadow, combining to form a mini island, around which a lighter energetic “current” flows along the bottom of the picture, curving around the red flowers in the lower right corner. Some mysterious force seems to be afoot here — as if van Gogh senses and renders some unseen magnetic energy or field.

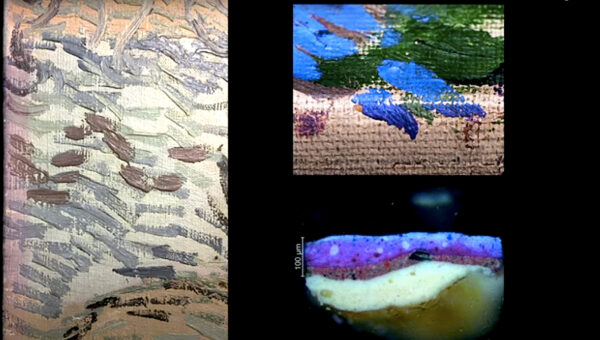

When she was employed at the Nelson-Atkins, Myers noticed that, in his letters, van Gogh described purple shadows that are currently blue. This led her to investigate the properties of the paints utilized by the artist. Van Gogh knew that certain recently developed pigments (which were made from organic substances rather than minerals), were unstable and fugitive. As he told Theo in a letter from around April 11, 1888: “all the colours that Impressionism has made fashionable are unstable, all the more reason boldly to use them too raw, time will only soften them too much.” He evidently did not realize just how much they would fade. As a consequence, the complementary color contrasts that van Gogh so often devised (violet and yellow; red and green) were soon muted by the fading of the red pigments he deployed.

Photographs of edges of two canvases by van Gogh and a paint sample. Photo: “Conservation Spotlight: Vincent Van Gogh, 2021.” In the photo on the left, one can see that on the top and left edges of van Gogh’s painting (which were protected from ultra-violet light by the edges of the frame) are more colorful than the rest of the painting because the red pigments he used did not fade very much in those protected areas. In the photo in the upper right, one can see that the frame protected the bottom edge of the painting from fading. One can see the presence of more red paint (which van Gogh often mixed with white). One can also see a violet tint to the blue area that was protected by the frame, so it is evident that the light blue paint was originally violet.

The image in the lower right is a cross section of a paint chip taken from a van Gogh canvas. The area visible to the viewer is at the very top, where the paint has faded to blue. Just a little bit lower, we can see that the paint is more purple: this area has not faded, because the organic red colors that van Gogh mixed into it were protected by the now-faded layer above it. These three details show how violet colors have faded to blue, and pink and salmon colors have faded to a near white.

Sarah Everts discusses the effects of fugitive pigments in several of van Gogh’s paintings in a 2016 c&en article, including how a painting with pink roses faded noticeably in just the 17 years it hung in the house of the artist’s mother. Van Gogh: Irises and Roses (2015), a short Metropolitan Museum video, juxtaposes old color photographs to give an idea of how the pigments in the flowers faded (pink turned white and violet turned blue). It also reconstructs how the iris and rose still life paintings (also made at Saint-Rémy) would have looked before van Gogh’s paint faded. A longer video, Van Gogh at the Met: recent insights through technical examination (2020) treats this material comprehensively. Both videos also address other subjects, including some olive grove paintings.

Laura Eva Hartman, a DMA Paintings Conservator, discusses research on unstable pigments van Gogh utilized in several paintings in the DMA video Conservation Spotlight: Vincent Van Gogh (2021).

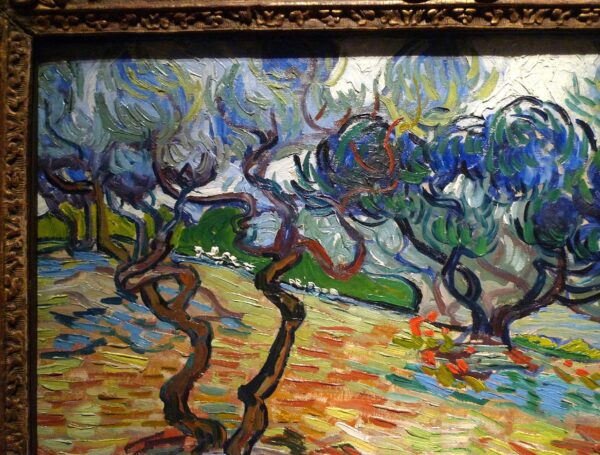

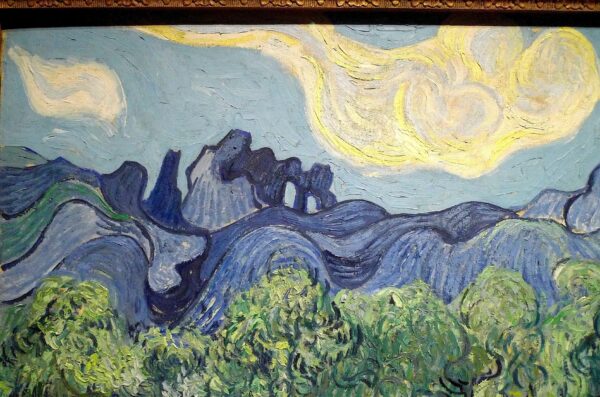

Vincent van Gogh, “The Olive Trees,” June 1889, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Among the olive grove paintings, the one at MoMA represents van Gogh’s greatest departure from the motif. What first appears to be a green stream or path in the lower right corner of the MoMA picture quickly splits in two and becomes unhinged from the soil, like a molten emerald lava flow floating above the earth. Or perhaps it is a visualization of the mistral, the often-ferocious cold, piercing wind that made it impossible to paint outdoors. The mistral, which haunts the region as the seasons change and is said to have the power to drive men mad, was mentioned by van Gogh in 45 letters between March of 1888 and February 1890.

In the MoMA picture, the ground itself seems to be segregated into dissociated areas of light and dark. In photographs, one can see that the ground is built up slightly around the trunks (where the ground was mulched), and grass often grows thicker in proximity to the trunks. But van Gogh has greatly exaggerated this natural effect in this painting.

Vincent van Gogh, “The Olive Trees” (detail), June 1889, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The single strangest element, however, is the center of the sky, which is dominated by a strangely anthropomorphic cloud that resembles a bluish embryo within a lighter embryo. The two primary peaks in the background correspond to actual geographical forms, but van Gogh depicts them wildly out of proportion. In real life, Mont Gaussier on the right is massive, and the strange rock formation on the left is relatively small. Van Gogh equalizes them so that they can frame and “cradle” the doubly embryonic cloud that floats between them.

The deep blue hillocks, generous beneficiaries of a shipment of paint Theo sent to van Gogh that was also utilized in The Starry Night, bear a greater resemblance to camel humps than to any rolling hills I’ve ever seen. The tree trunks and branches seem more blue than brown. Before the paint faded, at least some of these blue touches would have been tinged with purple.

Nestled along the horizon of blue humps, the treetops merge into a single, unitary form that imitates the rhythmic hillock humps — as if all of creation were dancing to a shared cosmic tune.

The present picture and the painting we know as The Starry Night (which did not receive that name until 1927) were mentioned together in two letters van Gogh wrote to Theo. When MoMA acquired The Olive Trees in 1998, chief curator Kirk Varnedoe referred to it and The Starry Night as “virtually twinned” demonstrations of van Gogh’s “boldest, most innovative style.” He also declared: “after a century apart, day finally rejoins night in this amazing reunion” (“Day Meets Night in Whitney Bequest,” MoMA, October, 1998).

The first of the two letters mentioned above was on or around June 18, 1889, when the artist noted: “At last I have a landscape with olive trees, and also a new study of a starry sky.”

In his letter on or around September 20, van Gogh referred to the former painting as Night study and the latter as Study of olive trees.

He also explained the logic of three paintings in this letter:

The olive trees with white cloud and background of mountains [the present painting], as well as the Moonrise [Wheatfield with Sheaves and Moonrise] and the Night effect [The Starry Night] –

These are exaggerations from the point of view of the arrangement, their lines are contorted like those of the ancient woodcuts. The olive trees are more in character, just as in the other study and I’ve tried to express the time of day when one sees the green beetles and the cicadas flying in the heat.

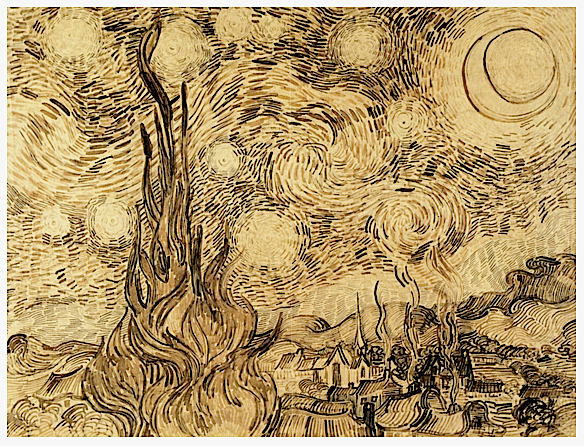

Vincent van Gogh, “The Starry Night,” reed pen drawing and wash, 1889. Formerly in the collection of the Bremen Kunsthalle, it was looted during World War II, and is now in Russia. Photo: Artnet. Van Gogh made drawings of his paintings in order to correct and refine the compositions and to have images to dispatch to Theo while the thick paint on his canvases dried. In his painting of “The Starry Night,” the lone cypress tree in the left foreground seems more like a magnificent work of architecture than a tree. It dwarfs the church steeple in the center of the painting, as if to say: “nature is great and organized religion is small.” In the drawing, the cypress tree is even more monumental — the natural equivalent of a cathedral. The central tendril — which is so tall its tip has to bend in order to remain within the frame of the drawing — emanates from a succession of onion-like domes. The landscape, which is rendered fairly indifferently in the painting, is tightened up: it is energized, and united into a series of wave-like, rhythmic forms. The moon is greatly enlarged. The stars are bigger, too. One of them is nestled within the tips of the cypress, creating a dynamic tension between foreground and background. Venus (the white heavenly body in the painting that is near the horizon) is less emphatic in the drawing because there is nothing to differentiate it from what are multi-hued stars in the painting.

The lines of force that map out the sky do indeed recall the often slightly curving forms found in archaic woodcuts (mentioned by van Gogh in the passage above). In drawings such as this one, van Gogh’s brushstrokes are translated back into graphic marks, providing us with a key to unlock the mysteries of his unique brushwork. Almost every element in the drawing is better and more powerful than the corresponding element in the painting. Only the swirling forms in the center of the sky disappoint, because they are smaller and much less emphatic than they are in the painting. Van Gogh has weakened the center of his cosmic vision, which, in my view, is the beating heart of his painting. It’s the single most astonishing, mysterious, sublime, and admired element in “The Starry Night.” We can only wish that van Gogh had painted multiple iterations of this composition.

The Starry Night and MoMA’s Olive Grove are kindred-spirit paintings: both feature bold exaggerations and stylistic accents the artist compared to archaic woodcuts.

From van Gogh’s perspective, these two paintings are relatively abstract. In the letter from around September 20, 1889, van Gogh speculates that Gauguin and Bernard were making similar paintings. Van Gogh only completed one more olive grove painting before he had a serious breakdown that interrupted his work. Thereafter, he retreated from the exaggerated stylizations and effects found in The Starry Night and MoMA’s Olive Grove. Van Gogh described his wavering artistic impulses in letters to Theo and Bernard.

Theo had specifically criticized The Starry Night in a letter from Paris on October 22, 1889, in which he said: “I consider that you’re strongest when you’re doing real things [he cited The Irises and The Tarascon Stagecoach, among other paintings] … The form is so well defined and the whole is full of colour.” Theo had an unfavorable view of Vincent’s newer paintings: “I clearly sense what preoccupies you in the new canvases like the village in the moonlight [The Starry Night] or the mountains [The Alpilles with a Hut], but I feel that the search for style takes away the real sentiment of things.”

Theo, of course, was an art dealer, who could not sell his brother’s tamest paintings, much less his wildest ones. From a purely formal viewpoint, van Gogh’s handling of paint (the individual brushstrokes and the unity of the entire web of brushstrokes) was best in paintings he rendered from life. But sometimes his conceptions were so dazzling, unique, and powerful — as in The Starry Night — that they more than compensated from a lapse in formal fluency.

The artist defended his stylistic choices in a letter to Theo on November 3:

For despite what you say in your previous letter, that the search for style often harms other qualities, the fact is that I feel myself greatly driven to seek style, if you like, but I mean by that a more manly and more deliberate drawing. If that will make me more like Bernard or Gauguin, I can’t do anything about it. But [I] am inclined to believe that in the long run you’d get used to it.

Finally, in a letter to Bernard around November 26, 1889, van Gogh noted that, under Gauguin’s influence, he “once or twice allowed myself to be led into abstraction” (he describes La Berceuse as one example). But he refers to abstraction as “enchanted ground” and, in the next paragraph, appears to rebuke painting from memory and imagination, and The Starry Night in particular: “However, once again I’m allowing myself to do stars too big, &c., new setback, and I’ve enough of that.”

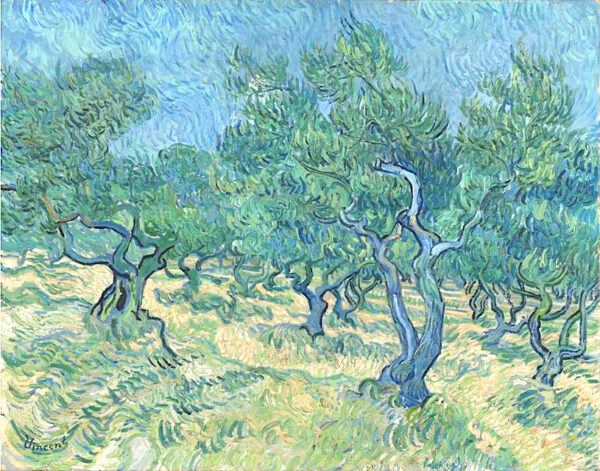

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Grove,” July 1889, oil on canvas, Kröller – Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands. Photographer: Rik Klein Gotink.

Unlike the MoMA version of olive trees, in which the olive leaves merged together to create a series of humpy hills, here the leaves terminate in points that thrust skyward. They are, nonetheless, very highly stylized, and their blue-green colors are quite artificial. The sky also seems to be charged with a crackling, curving, and vertically-oriented energy (perhaps inspired by woodcut techniques). The handling of the sky recalls the fields of force in the background of the famous self-portrait in the Musée d’Orsay, which van Gogh painted in Saint-Rémy.

No supercharged currents of any particular note continue along the ground, however, where each tree seems to be nestled in its own mini-hillock. The fact that this painting is signed has led some to speculate that the artist was likely particularly pleased with it. Or perhaps he was heartened by the direction his work was taking, since he was unaware of his imminent breakdown.

Van Gogh’s July Breakdown and his Olive Grove Paintings from September and October

Installation shot of two small olive grove paintings by van Gogh and Paul Gauguin’s “Christ in the Garden of Olives,” November, 1889. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Van Gogh suffered a severe breakdown in mid-July, which he reported to Theo on August 22, 1889:

This new crisis, my dear brother, came upon me in the fields, and when I was in the middle of painting on a windy day. I’ll send you the canvas, which I nevertheless finished. [The painting was Entrance to a Quarry.] And it was precisely a more sober attempt, matt in colour without looking impressive, broken greens, reds and rusty ochre yellows, as I told you that from time to time I felt a desire to begin again with a palette like the one in the north.

In a letter to Theo on or around October 8, 1889, van Gogh explained that he was fine between breakdowns:

As for me, my health has been good lately – I really think that Mr Peyron [the director of the asylum] is right when he says that strictly speaking I’m not mad, for my thoughts are absolutely normal and clear between times, and even more than before, but during the crises it’s terrible however, and then I lose consciousness of everything. But it drives me to work and to seriousness, as a coal-miner who is always in danger makes haste in what he does.

As van Gogh noted in the passage above, he lost consciousness during his attacks. Moreover, after the severe attack that interrupted his course of work on the olive grove paintings, his next efforts were more tentative — as evidenced by the two smaller paintings in the installation shot above (painted in September and October, respectively), as well as a third painting that is not in the DMA exhibition (painted in September). It apparently was not easy for van Gogh to get his groove back. We should not, therefore, attribute van Gogh’s unique artistic vision to disease, unlike — to cite one of the many authors the multi-lingual artist admired — the obviously mad narrator of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart (1843), who declared:

The disease had sharpened my senses — not destroyed — not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily — how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

Van Gogh feared his breakdowns, and that fear impelled him to work ever harder when he was in good health.

Van Gogh Criticizes Gauguin’s and Bernard’s Paintings of Christ in the Garden of Olives

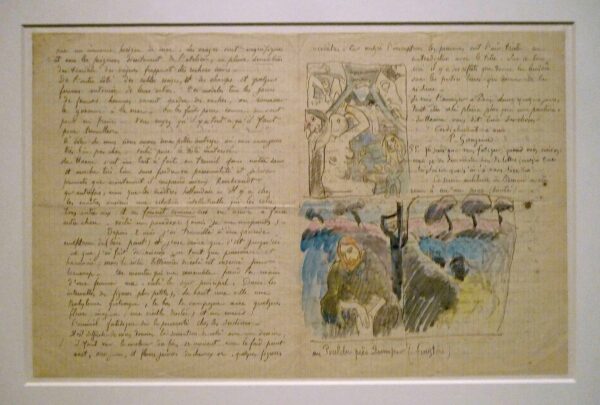

Paul Gauguin, letter to Vincent van Gogh with two sketches, c. November 10-13, 1889, ink and watercolor on paper. Collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Around November 10-13, Gauguin wrote a letter to van Gogh from Le Pouldu (illustrated above). He told van Gogh that he had a painting he thought would be of interest to him:

It’s Christ in the Garden of Olives – blue-green sky, dusk, trees all bent into a purple mass, ground violet and Christ wrapped in a dark ochre garment has vermilion hair. As this canvas isn’t destined to be understood I’m keeping it for a long time. [Which means that he was not sending it to Theo.] Included is this drawing, which will give you a vague idea of it.

Van Gogh apparently did not like the painting. Gauguin did not preserve the letter van Gogh wrote in response. But in his next letter to van Gogh, Gauguin defended experimentation and noted that he only made “one religious painting this year.”

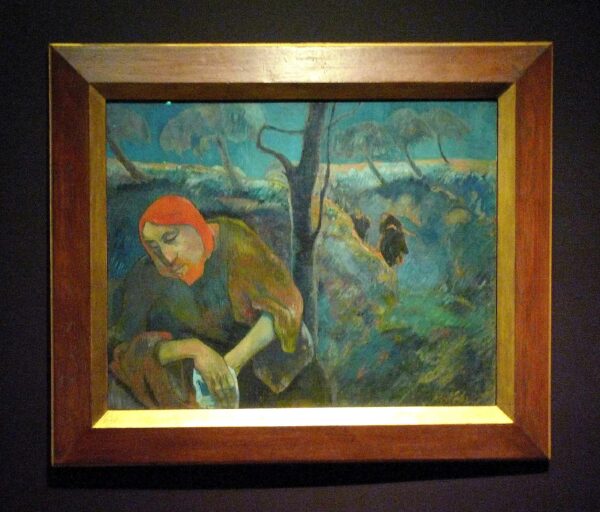

Paul Gauguin, “Christ in the Garden of Olives,” November 1889, oil on canvas, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In a letter to Bernard, Gauguin stated that it would be “pointless” to show the painting to Theo, who already had a number of religious paintings by Gauguin that he did not appreciate.

Émile Bernard, “Christ in the Garden of Olives,” November 1889, oil on canvas, location unknown. Photo: Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh at Saint-Rémy and Auvers, 1986? (Not in the DMA’s exhibition.)

Van Gogh berated Bernard in a long and relentless letter from around November 26, 1889. It is the same letter (quoted above) in which van Gogh dismissed his own Starry Night. Bernard had sent him six photos in his previous letter, most or all of which depicted his recent religious paintings. He blasts Bernard’s Adoration of the Shepherds: “the mother who starts praying instead of giving suck, the fat ecclesiastical bigwigs, kneeling as if in an epileptic fit, God knows how or why they’re there, but I myself don’t find it healthy.” Doubting Bernard’s sincerity, he compares the painting to Millet’s Birth of a Calf (1864) and declares: “one has to look for the possible, the logical, the true.”

Van Gogh made a thumbnail sketch of Bernard’s painting Red Poplars (1887), which he used to rail against another religious painting by Bernard with a very familiar subject:

And when I compare that with that nightmare of a Christ in the Garden of Olives, well, it makes me feel sad, and I herewith ask you again, crying out loud and giving you a piece of my mind with all the power of my lungs, to please become a little more yourself again.

Van Gogh does not beat around the bush:

The Christ carrying his Cross is atrocious. Are the splashes of colour in it harmonious? But I won’t let you off the hook for a commonplace — commonplace, you hear — in the composition.

After explaining how he had lost his way with abstractions (including The Starry Night), van Gogh describes two of his landscapes: The Garden of the Asylum and Wheatfield at Sunrise. Van Gogh explains that he intended to convey antithetical emotions in these two paintings:

A ray of sun — the last glimmer — exalts the dark ochre to orange — small dark figures prowl here and there between the trunks. You’ll understand that this combination of red ochre, of green saddened with grey, of black lines that define the outlines, this gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer, and which is called ‘seeing red.’ And what’s more, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly green and pink smile of the last flower of autumn, confirms this idea. [I have quoted only the last portion of a very long description.] Another canvas depicts a sun rising over a field of new wheat. Receding lines of the furrows run high up on the canvas, towards a wall and a range of lilac hills. The field is violet and green-yellow. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow aureole. In it, in contrast to the other canvas, I have tried to express calm, a great peace.

After these descriptions, van Gogh argued that his landscapes could convey the emotional equivalent of biblical stories, whether they be suffering or calming in nature. Then van Gogh pointedly told Bernard that he didn’t have to refer to the Bible to convey these feelings:

I’m speaking to you of these two canvases, and especially the first, to remind you that in order to give an impression of anxiety, you can try to do it without heading straight for the historical garden of Gethsemane; in order to offer a consoling and gentle subject it isn’t necessary to depict the figures from the Sermon on the Mount…

Van Gogh tells Bernard that he is right to be moved by the Bible, but that modern realities make it impossible to “abstractly… reconstruct ancient times in our thoughts.” Van Gogh adds that even the great Millet — who he says read only the Bible — almost never painted biblical scenes.

Near the end of the letter, van Gogh complains of his lack of models and noted:

Have just done 5 no. 30 canvases of the olive trees… What I’m making is harsh, dry, but it’s because I’m trying to reinvigorate myself by means of rather arduous work, and would fear that abstractions would make me soft.

Van Gogh felt that he needed the rigor of painting directly from the motif, even if he finished his paintings in his studio in the asylum.

Van Gogh noted to Theo that Bernard had probably never seen an olive tree. I doubt, however, that van Gogh was familiar with the olive trees in Gethsemane, which was the first olive grove I experienced. Individual trunks of these ancient trees are many feet in circumference. Sometimes they crowd together and seem like a wall. They bear little resemblance to the relatively scrawny trees that van Gogh painted in Saint-Rémy.

The Olive Grove Paintings in November and December

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Trees,” November 1889, oil on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Art, The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the same letter to Bernard from around November 26, van Gogh describes five large olive grove paintings that he had made in December:

So at present am working in the olive trees, seeking the different effects of a grey sky against yellow earth, with dark green note of the foliage; another time the earth and foliage all purplish against yellow sky, then red ochre earth and pink and green sky. See, that interests me more than the so-called abstractions.

Van Gogh would paint three more olive grove pictures in December.

On November 26, van Gogh also wrote to Theo, telling him:

I’ve been working this month in the olive groves, for they’d driven me mad with their Christs in the garden, in which nothing is observed. Of course there’s no question of me doing anything from the Bible – and I’ve written to Bernard, and also to Gauguin, that I believed that thinking and not dreaming was our duty, that I was therefore astonished when looking at their work by the fact that they give way to that. For Bernard has sent me photos of his canvases. The thing about them is that they’re sorts of dreams and nightmares… but it gives me an uncomfortable feeling of a tumble rather than progress.

Van Gogh added:

Well, to shake this off, I’ve been messing about in the groves morning and evening on these bright and cold days, but in very beautiful, clear sunshine, and the result is 5 no. 30 canvases which, with the 3 studies of olive trees that you have, at least constitute an attack on the problem.

Instead of imaginative “abstractions,” van Gogh produced five paintings of olive groves in November of 1889. The picture now in Minneapolis features a bright sun, which for van Gogh was an emblem of life. Contemporary viewers are accustomed to van Gogh’s large sun and his textured sky, but they must have been very novel effects for period viewers. Perhaps the leaves seem like the most realistic element in this painting. The trunks are strange; the ground and the shadows of the trees are extremely artificial-looking.

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Grove, Saint-Rémy,” November 1889, oil on canvas, Gothenburg Museum of Art, Sweden. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

This could be van Gogh’s boldest painting of olive trees, in part because the colors are relatively well preserved. In this painting, van Gogh made less use of fugitive pigments than in his other paintings (though the light blue shadows on the ground were originally purple). The varied coloristic effects are strong throughout the painting.

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Grove, Saint-Rémy” (detail of tree trunks), November 1889, Oil on canvas, Gothenburg Museum of Art, Sweden. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Van Gogh has rendered the tree trunks in a very anthropomorphic manner. One can almost read them as figural sculptures on plinths. Despite its somewhat abstracting qualities, the painting found favor with Theo, who judged it “superb” and exhibited it at the Indépendants exhibition in Paris in 1890.

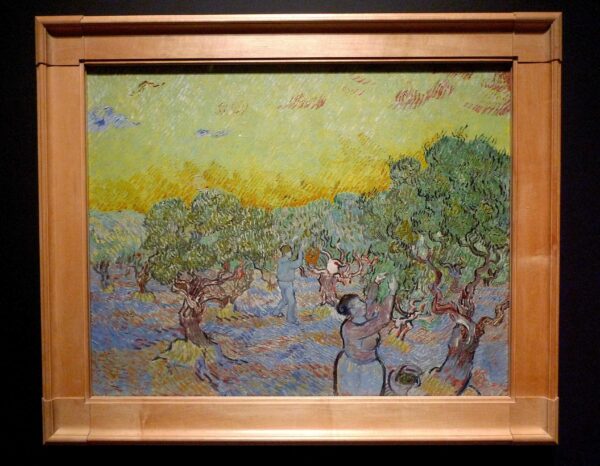

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers,” November 1889, oil on canvas, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers reprises the colorful picture at Gothenburg. But it looks bleached-out in comparison. That is because van Gogh utilized an abundance of pigments in the Kröller-Müller painting that have faded.

The tree trunks are also much less anthropomorphic than in the Gothenberg picture. Van Gogh — who so often decried his lack of models — was able to depict real people in the act of harvesting olives, which must have brought him great satisfaction. He always admired Millet’s depictions of laborers. That human presence presumably mitigated against what was perhaps an unconscious need to transform tree trunks into twisted, human-like forms.

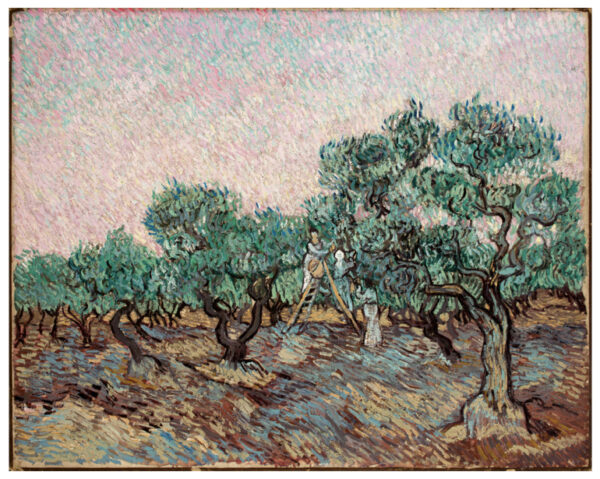

Vincent van Gogh, “Women Picking Olives,” November 1889, oil on canvas, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation, Athens. Photo: Goulandris Foundation. (Not in the DMA’s exhibition.)

Now I compare three closely related paintings that are not in the exhibition. As noted in my Glasstire article on deaccessioning that is linked above, the Goulandris painting is the plein-air version of this motif of three women picking olives. It was sold by the Metropolitan Museum in 1972 and bought by Goulandris. (Had the Met retained the picture, it would have the most realistic and the most stylized of the three paintings.)

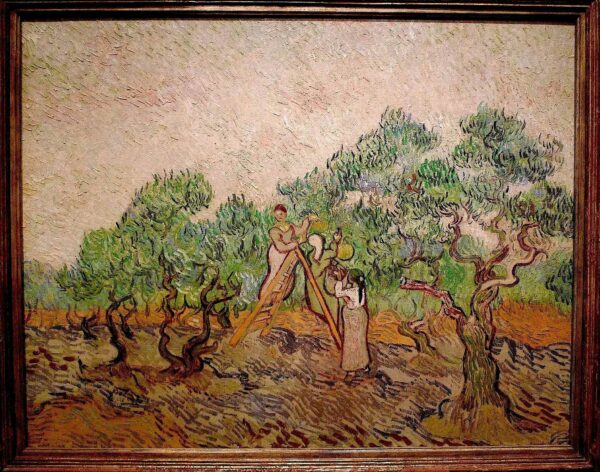

Van Gogh described these three paintings to Theo in a letter dated January 3, 1890:

Women picking olives – I´d intended this painting for our mother and sister [the painting illustrated below, now at the Metropolitan Museum] so that they might have something a little studied. I also have a repetition of it [the painting illustrated below, now at the National Gallery] for you, and the study (more coloured with more solemn tones) from nature [the Goulandris painting illustrated above].

In the Goulandris painting, the leaves in particular have the look of having been painted from life. They are a deeper green. They also have a higher degree of specificity and a clearer connection to the branches from which they emerge than the replicas. The women look relatively casual and un-posed.

Vincent van Gogh, “Olive Orchard,” November 1889, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. (Not in the DMA’s exhibition.)

This picture, in the National Gallery in Washington D.C., is the first of two replicas of the Goulandris painting that van Gogh made in his studio in the asylum. (As previously noted, it is prohibited from traveling.) This painting was intended for Theo. The Dale picture is considerably more stylized than the Goulandris version. The women are monumentalized and centered within the picture. They also have simpler, clearer, less naturalistic poses.

The trunks of the three trees in the foreground are accentuated, while the others fade and recede into the background (relative to the Goulandris painting). The trunks and branches are thinner, lighter, and much more energetically twisted. The branch in the right foreground corkscrews dramatically. One of the thin trunks to the left of the women is so twisted it resembles a Solomonic column. The sky is more green than pink (at least it is now).

Vincent van Gogh, “Women Picking Olives,” November 1889, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 1995, bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. (Not in the DMA’s exhibition.)

This is the second (and final) replica of the Goulandris picture. The figures and the trunks of the trees are more simplified than in the National Gallery picture. The olive leaves in the foreground are disarticulated from the branches, forming fiery clusters of green. The mass of greenery in the background merges together. The sky is rendered with dramatic clusters of curvilinear pink brushstrokes. The ground is made up of three bands: a steel-gray area tinged with purple divides yellow ochre areas in the foreground and background.

As noted above, van Gogh intended the painting for his mother and sister, though they never took possession of it. Van Gogh mentioned it several times in his correspondence. He wrote to his sister Willemina on January 20, 1890:

I hope that the painting of the women in the olive trees will be a little to your taste – I sent the drawing of it to Gauguin just recently and he told me that he thought it good, and he knows my work well, and he isn’t embarrassed to say so when it isn’t right. You would naturally be quite free to take another of them in its place if you wished, but in the long run I almost dare believe that you’d return to this one.

Summing up my response to the olive grove portion of this exhibition, for sheer handling of paint, I appreciate the Nelson-Atkins picture the most. In terms of color, I like the Scotland National Gallery and the Gothenburg paintings. For conception and iconography, I prefer the MoMA and Gothenburg examples.

In the January 3, 1890 letter to Theo linked above, van Gogh mentions four additional olive grove paintings, among other works, and advises Theo on framing:

Please don’t look at them without putting them on stretching frames and framing them in white… Thus the rain, the grey olive trees, one can scarcely see them without the frame.

Van Gogh preferred simple, unobtrusive frames rather than gilded, ornately carved frames. I have included the frame in the Annenberg painting to show how taste in framing developed among dealers and collectors. Many museums have gradually replaced such frames with simpler ones, such as the ones on several paintings in Van Gogh and the Olive Groves. Fishing in Spring (1887), a painting borrowed from the Art Institute of Chicago that is visible in the installation shot of the first gallery in the exhibition, is equipped with a small white frame, in keeping with the artist’s preference.

Research Findings on Display

View of gallery with educational component of Van Gogh and the Olive Groves. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

A large U-shaped gallery is situated between the olive grove paintings and the final two galleries. It does an excellent job of presenting the conclusions of the research undertaken for the exhibition. Large graphic displays explain the primary aspects of the research program, commencing with definitions of art terms and extending to the artist’s use of fugitive materials and even to a reconstruction of the bolt of canvas van Gogh used for his olive grove paintings (the latter helped to establish their chronology). The only discordant notes stemmed from squeaking apparatuses. Lights with adjustable necks (used to demonstrate the use of raking light to reveal paint texture) and a hinge that covered a hidden answer squeaked so loudly that they sounded like haunted house sound effects in the adjacent galleries.

I did not read the catalogue because the museum declined to send me a review copy. On the basis of labels, wall texts, a filmed interview by Art This Week and a filmed lecture at the DMA, I can see that my views differ with those of co-curator Myers on a couple of points. I don’t think that van Gogh had a “proprietary” attitude towards the theme of Christ in the garden of Gethsemane: he was opposed to contemporary religious painting in general. Additionally, van Gogh was at pains to create an alternative to religious art based on the natural world. I think Myers goes too far in interpreting his art in Christian terms.

Impressions of Provence

Installation shot with four of the five paintings in the Impressions of Provence section of the exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Van Gogh wanted to make additional series of Provencal motifs, such as cypress trees and the Alpilles Mountains, but he left the asylum before they could be completed. He feared its religious origin and orientation contributed to the religious hallucinations he suffered during his breakdowns.

Vincent van Gogh, “A Wheat Field with Cypresses,” September 1889, oil on canvas, The National Gallery, London, Courtauld Fund, 1923. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The most important of these paintings of Provencal motifs is the London version of A Wheat Field with Cypresses. It is an excellent stylized repetition of the prime version in the Metropolitan that was painted the previous summer. The Met painting is one of van Gogh’s very best paintings. Since it came to the museum with the Annenberg collection, it cannot be lent. All three versions of the painting (one is in a private collection) feature cypresses (symbols of eternity van Gogh compared to Egyptian obelisks), wheat fields, the Alpilles, and even a small group of olive trees (in the left foreground). The London picture really sings against the dark blue walls in the DMA exhibition.

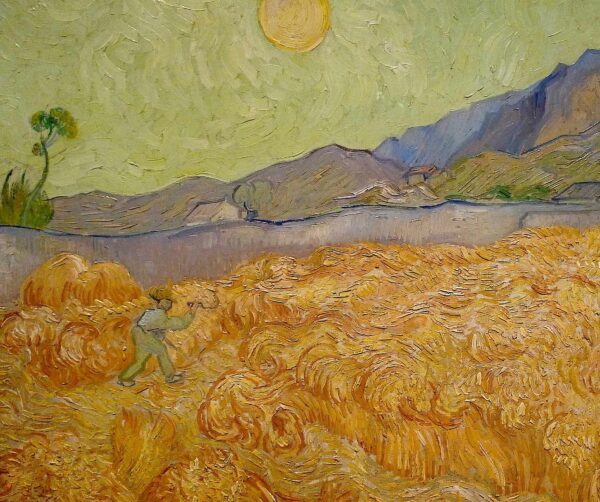

Vincent van Gogh, “Wheat Field with a Reaper” (detail), September 1889, oil on canvas, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

I skip over the very fine Landscape at Saint-Rémy (Enclosed Field with Peasant) at the Indianapolis Museum of Art from October of 1889 in order to discuss its pendant, Wheat Field with a Reaper. Van Gogh painted this view from the barred window of his asylum several times.

The artist explained his ideas about what became two versions of this painting — as well as the fears about his health — in a letter to Theo on September 6, 1889. It is worth quoting at length:

Work is going quite well – I’m struggling with a canvas begun a few days before my indisposition. [The version of Wheat Field with a Reaper in the Kröller-Müller Museum. It was begun in June before his attack, and he notes its completion later in this letter.] A reaper, the study is all yellow, terribly thickly impasted, but the subject was beautiful and simple. I then saw in this reaper – a vague figure struggling like a devil in the full heat of the day to reach the end of his toil – I then saw the image of death in it, in this sense that humanity would be the wheat being reaped. So if you like it’s the opposite of that Sower I tried before. But in this death nothing sad, it takes place in broad daylight with a sun that floods everything with a light of fine gold. Good, here I am again, however I’m not letting go, and I’m trying again on a new canvas. [The picture illustrated above, with a green sky, in the Van Gogh Museum.] Ah, I could almost believe that I have a new period of clarity ahead of me. And what should I do – continue here for these months, or move – I don’t know. The thing is, when the crises present themselves they aren’t amusing, and to risk having an attack like that with you or others is serious.

My dear brother – I’m still writing to you between bouts of work – I’m ploughing on like a man possessed, more than ever I have a pent-up fury for work, and I think that this will contribute to curing me.

… Phew – the reaper is finished, I think it will be one that you’ll place in your home – it’s an image of death as the great book of nature speaks to us about it – but what I sought is the “almost smiling”. It’s all yellow except for a line of violet hills – a pale, blond yellow. I myself find that funny, that I saw it like that through the iron bars of a cell.

Ah well, do you know what I hope for once I set myself to having some hope, it’s that the family will be for you what nature is for me, the mounds of earth, the grass, the yellow wheat, the peasant. That’s to say that you find in your love for people the wherewithal not only to work but the wherewithal to console you and restore you when one needs it. So please don’t let yourself be exhausted too much by business matters but take good care of yourselves, both of you – perhaps in a not-too-distant future there’s still some good.

Van Gogh says that nature, including the earth and the grass, is his solace, his consolation, his “family.” Elsewhere, he refers to his paintings as his progeny. He imagines death as an “almost smiling” harvest of a sun-ripened crop. Van Gogh also expresses fear that he could harm others during an attack.

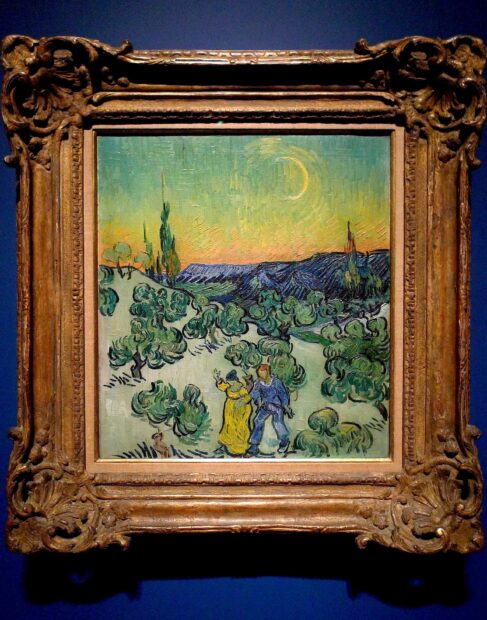

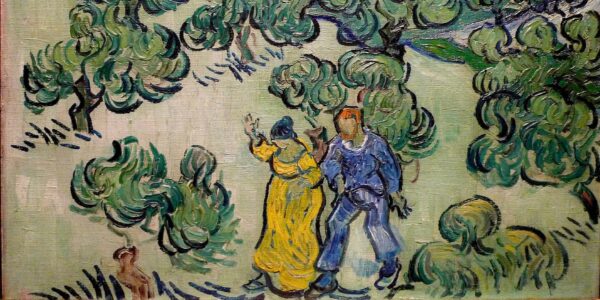

Vincent van Gogh, “A Walk at Twilight,” 1889-1890, oil on canvas, Museu de Arte se São Paul, Assis Chateaubriand, Purchase 1958. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

A Walk at Twilight is often viewed as a retrospective summation of Provance, foregrounded by a fantasy of the human companionship van Gogh was never able to find. The landscape has characteristic Provencal features, including olive trees, cypresses, and mountains. In this instance, I think the elaborate frame contributes to the charm of this small painting.

Vincent van Gogh, “A Walk at Twilight” (detail), 1889-1890, oil on canvas, Museu de Arte se São Paul, Assis Chateaubriand, Purchase 1958. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Many commentators regard the red-haired man as a self-portrait of van Gogh, accompanied by a beautiful Arlesienne. The artist had fantasized about his the beautiful women of Arles since his days in Paris. The washed-out foreground contributes to the painting’s oneiric qualities. It is as if the dream is so vague that neither the ground nor the couple’s faces possess any detail. It seems the artist himself could not quite picture it.

After the Olive Groves

Installation shot with the three paintings in the After the Olive Groves section of the exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Van Gogh moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, a village 20 miles northwest of Paris, in May of 1890, where he committed suicide in late July, after completing a painting a day. (See the Van Gogh Museum’s “The End of a Difficult Road.”) The exhibition terminates with three of van Gogh’s last pictures, from a series of double-square paintings.

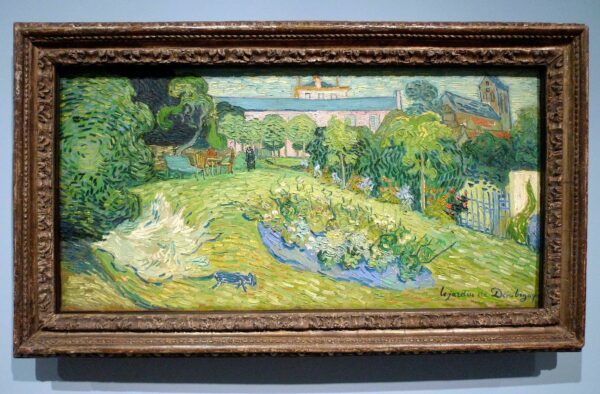

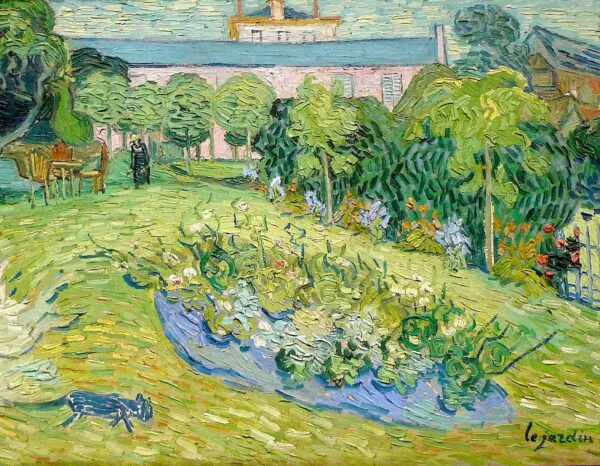

Vincent van Gogh, “Daubigny’s Garden,” July 1890, oil on canvas, Rudolf Staechelin Collection. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

My favorite among the last three pictures in the exhibition is the one painted in the garden of the Barbizon painter Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), who had been the most famous resident of Auvers. I puzzled over it many times while it was loaned to the Kunstmsuem in Basel, not certain what I thought about it. Annenberg, incidentally, acquired two extraordinary van Goghs from the Staechelin collection: the aforementioned Wheatfield with Cypresses, and the finest of the artist’s five versions of La Berceuse. I rank the latter among the best van Gogh portraits in the U.S., despite the artist’s self-criticism of this series.

Almost without exception, I prefer van Gogh’s most thickly painted works, and especially the paintings in which he utilized swirling or curvilinear brush strokes. In Daubigny’s Garden, van Gogh utilized a variety of techniques. In the center of the composition, van Gogh has provided a bouquet of flowers — rendered in the style he perfected at Arles — seemingly deposited in the middle of a landscape. Elsewhere, the short strokes so familiar from the November olive grove paintings are much in evidence. Sometimes they blend in with their surroundings, as in the grass. At other times, they function as quasi-contours painted over greenery, as in upper center and in the blob of shrubbery on the far right.

Vincent van Gogh, “Daubigny’s Garden” (detail), July 1890, oil on canvas, Rudolf Staechelin Collection. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Strangely enough, with only the assistance of some rudimentary contours, dark parallel strokes also compose the body of the cat. Daubigny’s Garden is one of van Gogh’s most eclectic works from this period.

The olive tree painting with the Pointillist sky in the Annenberg collection at the Metropolitan has some very strange additions: it is overlaid with small, thickly textured clouds. I find the lower part of that painting — and the similar one in the van Gogh Museum — to be harsh and dry (to use van Gogh’s own words). Perhaps that eclectic sky helped pave the way for van Gogh’s mixture of techniques in his subsequent paintings. In the end, I have come to appreciate eclecticism. Among van Gogh’s last paintings, Daubigny’s Garden is one of my favorites.

Conclusion

When temporary exhibitions are done well — as is the case with Van Gogh and the Olive Groves — they add greatly to our knowledge of artists, history, and art. If too many museums had loan prohibitions, it would be impossible to have an exhibition such as this one. It is unfortunate that loan restrictions prevented three olive grove paintings from being displayed in Dallas or Amsterdam. As noted above, the prime version of Wheat Field with Cypresses, also an Annenberg picture, is similarly restricted. Van Gogh and the Olive Groves underscores the importance of cooperation between museums. Fortunately, the owners of all of the paintings in this series consented to participate in the research that resulted in this exhibition.

I permit van Gogh to have the last word, from a letter to Theo from Arles, dated July 9 or 10, 1888:

But the sight of the stars always makes me dream in as simple a way as the black spots on the map, representing towns and villages, make me dream.

Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be less accessible to us than the black spots on the map of France.

Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star. What’s certainly true in this argument is that while alive, we cannot go to a star, any more than once dead we’d be able to take the train. So it seems to me not impossible that cholera, the stone, consumption, cancer are celestial means of locomotion, just as steamboats, omnibuses and the railway are terrestrial ones.

To die peacefully of old age would be to go there on foot.

For the moment I’m going to go to bed because it’s late, and I wish you good-night and good luck.

Handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.

2 comments

Great article, Bravo!!!

Thanks, Roberto. I’m glad you liked it.