Octavio Medellín (1907-1999), an important but underappreciated Mexican-born artist and instructor who worked in Texas for six decades, has been accorded his first museum retrospective. Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form, a remarkable exhibition of 80 works curated by Mark A. Castro, The Jorge Baldor Curator of Latin American Art, is at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) through January 15, 2023. Medellín was an extraordinarily talented sculptor who utilized many materials during his long career. The 30 sculptures in the exhibition, which date from 1926 to 1995, highlight his skill and creativity in that medium.

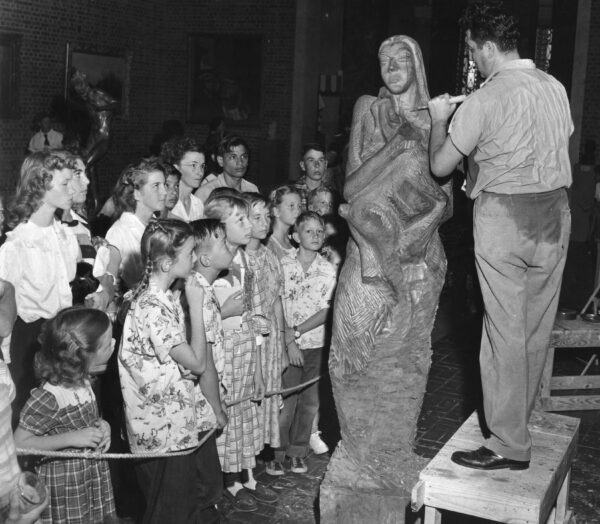

Photograph of Octavio Medellín carving “Genoveva,” c. 1948-49. Courtesy of Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University. Photograph: Jay Simmons.

Agustín Arteaga, the DMA’s Eugene McDermott Director, declared in a statement:

This recognition for Octavio Medellín, an important artist in the history of our city and Museum, is long overdue. We are elated to honor his career and contribute new scholarship on his significant and diverse bodies of work.

Noting the artist’s multiple roles as artistic exemplar, teacher, and mentor, Arteaga added: “We hope this exhibition cements his place among the most important artists working in Texas in the 20th century.”

The exhibition easily accomplishes that task — and more. I was so impressed with Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form that I am writing a two-part review in order to make a large quantity of the artist’s oeuvre more readily available. This first part treats Medellín’s work in wood, stone, and terracotta through 1949. Part Two treats his later sculptures in these mediums, including his monumental red mahogany sculpture The History of Mexico (1950). It also examines some of Medellín’s numerous public commissions, as well as work in diverse mediums, including graphic arts, metal, and ceramics.

I begin with an overview of Medellín’s life through 1949, which draws on Castro’s introductory essay in the catalogue Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form (Dallas Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022). Castro also covers some of this material in a lecture on Medellín for the Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art’s (CASETA) 2021 Virtual Fall Forum.

Medellín’s Origins in Mexico and Immigration to San Antonio

The Medellín family, c. 1915. Courtesy of Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University, gift of Octavio Medellín. Octavio, about age eight, is seated in the front, on the far right. His mother and father, Manuel Medellín and Herlinda Torres Medellín, are in the top row, far left.

Born in the town of Matehuala (near San Luis Potosí), Medellín was of Otomí ancestry. His father Manuel, who instilled a love of art in the young Octavio, was a mineworker. Due to violence caused by the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, Medellín’s family moved within Mexico several times. In 1920, they immigrated to San Antonio, Texas.

Medellín worked a number of odd jobs in San Antonio to assist his family. He also took night classes at the San Antonio Art School (affiliated with the Witte Museum) in the early 1920s. Medellín said his introduction to sculpture came when he spotted an interesting log, which he dragged home and began to carve. Medellín studied painting at the San Antonio Art School with José Arpa y Perea (1858-1952), a Spanish-born painter who arrived in San Antonio in 1923. Arpa, who founded his own art school — a precedent that may have inspired Medellín to found his own school many years later in Dallas — was joined by his nephew Xavier González, a painter, sculptor, and printmaker, with whom Medellín also studied. Medellín credits Arpa and González, who had both spent time in Mexico, as his most important teachers.

Chicago, Mexico City, and the Gulf Coast

In 1928, Medellín ventured to Chicago for eighteen months and studied briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he took life drawing classes at night. He was finally able to see the work of U.S. sculptors he admired, including Alexander Archipenko, John B. Flannagan, and William Zorach (the latter two artists were early practitioners of direct carving). Medellín’s only known sculpture from his Chicago period is Tehuana (1928-29, pecan wood, present location unknown), which is discussed below.

Medellín traveled to Mexico City in 1929 or 1930, where he was denied admission to the National School of Fine Arts due to his lack of formal training. He nonetheless learned about and had first-hand exposure to Mexican Modernism. Medellín met a number of important artists, including Jean Charlot, José Clemente Orozco, Frida Kahlo, and Carlos Mérida. He maintained a friendship with Mérida. Additionally, Medellín explored rural areas of Veracruz along the Gulf Coast on foot, where he met many artisans. He also appears to have visited the pre-Hispanic ruins of El Tajín. This trip deeply influenced Medellín’s early sculpture style.

The Return to San Antonio

Returning to San Antonio, in late 1930 or 1931, Medellín carved a remarkable series of works in Texas limestone, including Thinking Girl (1930), Primitive Woman (1931-35), and The Spirit of the Revolution (1932-33).

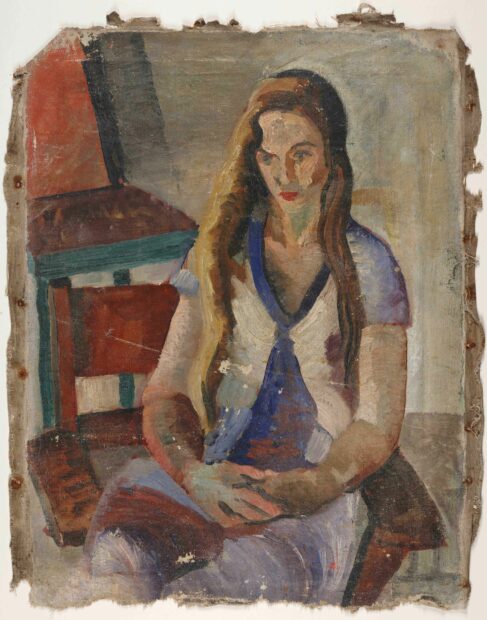

Octavio Medellín, “Portrait of Cecilia Neuhiesel Steinfeldt,” c. 1927-30, oil on canvas. Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University, gift of Octavio Medellín.

Medellín garnered recognition for his works executed in wood, clay, and stone through exhibitions in San Antonio. He also began teaching at the Witte Museum. Medellín got to know some of the central figures in the local arts scene, including the curator and art historian Cecilia Neuhiesel Steinfeldt, and the painter Julian Onderdonk.

Octavio Medellín at work on his fountain at the Villita Street Art Gallery, 1937-38. Published in the San Antonio Light newspaper. Photograph: screenshot from Curator Mark Castro’s 2021 CASETA lecture.

Medellín co-founded a gallery with 25 other artists in the La Villita neighborhood of San Antonio in 1934. His now-lost fountain at the Villita Street Art Gallery, c. 1937-38, as noted in a San Antonio Light article (“Fountain of Beauty, Artist Shows South Texas Clay Value,” January 16, 1938), was made from “pluk clay” from Elmendorf, Texas. Medellín, the article reports, had been at work on the fountain for two months, and planned to install it in the rear of the gallery the following week, “after baking.” After six years of working with clay, the artist had “only recently discovered the possibilities in Texas clays.”

Medellín married in 1935 and began a family. He taught courses at the Witte and La Villita, and he also worked at other jobs. According to the San Antonio Light:

For 12 years Medellín has worked at his art. Most of the time he worked and studied after he had completed his day’s task as a stock clerk in a plumbing concern here (“Art Exhibit Starts Here,” December 28, 1939).

Artist and patron Lucy Maverick visited the Villita Street Art Gallery and was very impressed with Medellín’s Thinking Girl (1930), which was sourced from local limestone. She wanted to buy it, and after some hesitation, Medellín sold the sculpture to her. Maverick subsequently lent it to the American Modern Art exhibition that was part of the New York World’s Fair in 1939. Maverick also joined the gallery as an artist before it opened.

“Villita Art Gallery to Open,” an undated, unidentified newspaper clipping at the Witte museum that must date from 1934, says the “Villita Street Gallery” was to open in May in “a lovely old stone house.” The article adds: “It is hoped that other congenial groups will organize and form their own galleries which will stimulate artistic work and also preserve these old houses…” Lucy Maverick, Agatha Maverick Welsch, and Eleanor Onderdonk were among the other artists affiliated with the gallery.

Most importantly, Lucy Maverick became Medellín’s patron and a steadfast enthusiast of his work. Maverick’s economic support enabled him to quit all of his jobs to focus on his artistic work.

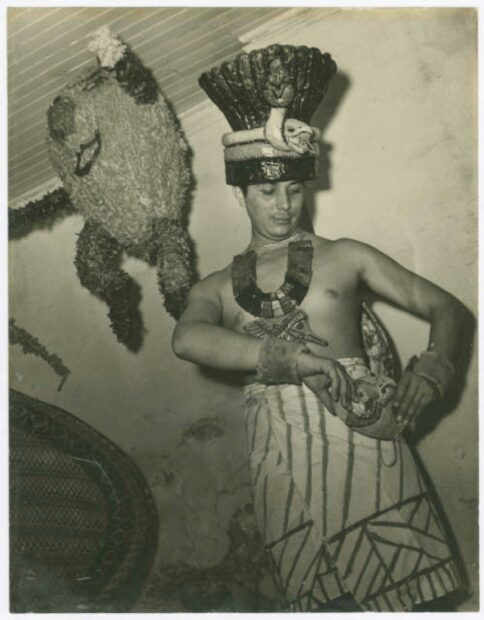

Photograph of Octavio Medellín in Mayan costume at Artist’s Ball in San Antonio, 1938 or 1939. Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University, gift of Octavio Medellín.

The Bywaters Special Collections entry on the above photograph notes that Medellín wrote on the reverse: “Octavio Medellin in Mayan Costume, won my trip to N.Y. City at Artist Ball, S.A. TX. 19 1938.” The DMA catalog also uses the 1938 date. However, the December 28, 1939 San Antonio Light article cited above says Medellín won the “most unique costume” at the ball in April, and that “he has just returned from New York where he spent 10 days visiting art galleries and museums and the fair.” The latter is a reference to the New York World’s Fair, where Thinking Girl was exhibited.

Lucy Maverick had traveled extensively in Latin America. She was an important collector who knew major artists in Mexico, and she also had participated in archaeological digs in Mexico and Guatemala. See The Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas entry on Lucy Maverick.

Maverick encouraged Medellín to make an extensive research trip to Mexico. However, he was reluctant to go without his family. Maverick generously sponsored a six-month long trip to the Yucatán for Medellín and his wife and two children in 1938. In Mexico, he sketched and photographed Maya ruins at Chichén Itzá and other sites. This trip inspired a group of Maya-influenced works, a number of which are featured in the exhibition, including prints, drawings, and decorative objects. The pre-Hispanic sculptures and relief carvings also exerted a more general influence on Medellín’s work.

Returning to the question of what year Medellín won best costume at the San Antonio ball, additional evidence can be found in the centerpiece of his costume: the hummingbird ornament that he wears on his chest is adapted from a relief on the Temple of the Jaguars at Chichén Itzá.

Octavio Medellín, “Untitled” (Hummingbird inspired by relief carving, Temple of the Jaguars at Chichén Itzá), 1975, six color block print, sheet: 9 ½ x 8 ¾ in. Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University, gift of Octavio Medellín. Photograph: Google Arts and Culture.

Several prints of hummingbirds inspired by the Chichén Itzá relief are in the exhibition, including the one reproduced above. An SMU blog from 2014 reproduces Medellín’s photograph of the damaged relief, a drawing by him that is an imaginative reconstruction of the relief (misidentified as a tracing on the blog), and the print reproduced above.

Given the 1939 date of the San Antonio Light article, and the fact that he spent half of 1938 in Mexico, could Medellín have misdated his inscription on the verso of the costume photograph, which was possibly written years after the fact?

Over 200 of Medellín’s graphic works and photographs of pre-Hispanic sculptures are available on Google Arts & Culture. An enormous trove of Medellín material, including his archives, is housed in the Bywaters Special Collections at Southern Methodist University (SMU).

Octavio Medellín, Wall Fountain Based on Inca Relief, c. 1936-37, Maverick Homestead Ranch, Boerne, Texas. Photograph from the Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University, gift of Octavio Medellín.

In exchange for travel funds for his family, Medellín made a wall fountain for the Maverick ranch in Boerne (in the Texas Hill Country north of San Antonio), based on a relief his patron had seen in Peru. Incidentally, the expression “maverick” derives from Samuel Augustus Maverick’s (1803-1870) unbranded cattle. While the New York Times article linked here emphasizes the Maverick family’s liberal bona fides, it should be noted that Samuel Maverick, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence and an early Texas land baron, was a slaveholder (his namesake forebear was one of the first men to bring enslaved people to the colony of Massachusetts). Lucy was Samuel’s granddaughter, and the cousin of Maury Maverick, a congressman (1935-38) and mayor of San Antonio (1939-41) whose pet local project was the restoration of La Villita.

Medellín in the Dallas Metroplex

When Medellín returned to San Antonio in 1938, he exhibited his drawings and paintings at the Villita Street Art Gallery. They impressed Dr. Cora Stafford, who was the director of the College of Visual Arts and Design at North Texas State Teacher’s College (now the University of North Texas) in Denton. Despite Medellín’s lack of academic credentials, she gave him the opportunity to teach sculpture in the summer of 1940. Medellín was subsequently offered a permanent position, but he only stayed about two years because he went to work in an aviation plant in Grand Prairie in 1942 (the year he became a U.S. citizen) to support the war effort.

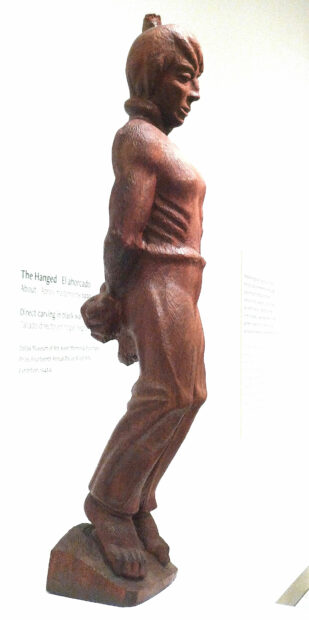

Medellín was quickly garnering both regional and national attention. His Thinking Girl (1930) was exhibited at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. In 1940, At the Stake (1938) got honorable mention at an exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (DMFA, today the DMA), while The Hanged (1939) received the Kiest Memorial Prize in 1943. The DMFA gave Medellín a solo exhibition in 1942.

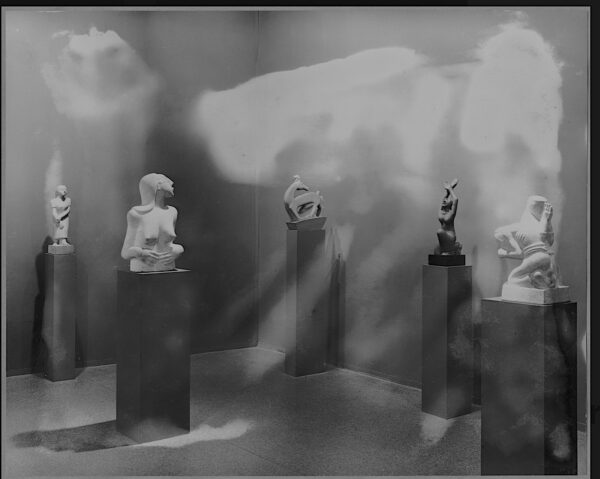

Medellín’s biggest artistic triumph would come in New York in 1942, when the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) selected seven of his works for a traveling exhibition.

Installation shot of five of seven Octavio Medellín sculptures in the exhibition “Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States,” 1942, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph: Museum of Modern Art.

From left to right, the sculptures in the above shot are: Waiting Figure (1940), Primitive Woman (c. 1931-35), Doe and Fawn (1939), Holy Roller (1931), and Penitentes (1940). Mad Moses (1936) and At the Stake (1938) are not pictured.

Monroe Wheeler, then MoMA’s Director of Exhibitions and Publications, noted in a museum press release that the exhibition Americans 1942:18 Artists from 9 States, organized by Associate Curator Dorothy C. Miller, consisted of work from outside of the metropolitan New York area. It was the first of several annual exhibitions that focused on art in the U.S. Wheeler says Miller spent months scouring the country looking for “the best work of artists, many of them little known — in some cases entirely unknown — to the New York art world.” After its premiere at MoMA, the exhibition was presented at other museums and galleries.

Medellín’s complete statement in the MoMA catalog is reproduced below in italics. He begins by noting fealty to the earth, to common people, and to everyday life. Medellín eschews “politics” and “sophisticated ideas:”

I believe that sincere art must be elemental and close to the earth — a symbol of the people.

The trend of my art is toward the common people and everyday life, the kind of people and environment I myself come from. It is entirely away from politics and sophisticated ideas.

Medellín is a proponent of direct carving (a term I discuss below), which he connects to indigenous traditions:

I think, as did the prehispanic and colonial Indian sculptors, that carving directly in stone is the only way to reach massive, round, and definite forms.

Finally, Medellín expresses a preference for stone, and for local stone in particular. He is cognizant of the unique qualities of particular types of stone, and he expresses a “truth to materials” philosophy:

Stone is beautiful in itself and does not admit of any tricks. It makes one desire to bend its hard surface into form but not to take advantage of and destroy its character.

All of the stone used in my work comes from Texas quarries. Some pieces are carved in limestone from quarries located near Austin, Texas. A very compact, semi-hard stone, it gives a beautiful texture when carved. I also use a rose-colored sandstone from west Texas. In color and grain it is similar to petrified wood and has a very special quality. I have also used a gray sandstone from southwest Texas, a hard stone that must be treated in a rough, coarse way.

Direct carving is a technique and philosophy that is diametrically opposed to the academic practice and tradition of carving. Academic artists underwent extensive training in order to create conventionally proportioned figures. They made exacting, small-scale models, which could be enlarged by studio assistants to any size with the aid of a mechanical device known as a pointing machine.

Direct carvers, on the other hand, worked more intuitively. They made unique works that were not rigorously pre-planned, and they in effect responded to the particular characteristics of individual pieces of wood or stone. Direct carvers selected their materials with great care for their inherent properties, and sometimes for their specific forms. Direct carvers essentially believed they were collaborators with their chosen materials. Some expressed a spiritual connection to particular substances. They sought to highlight rather than efface the particular characteristics of a given sample of rock or piece of wood.

Medellín revered John Bernard Flannagan, who often used field stones rather than quarried stone. A text on the David Smernoff Gallery website declares that in Flannagan’s work: “one senses his utter respect for natural form and texture, as if the living presence of each stone contributed to the life of the subjects chiseled into and released from it.” The last point parallels Michelangelo’s claim that his statues were pre-existing, and that he merely released them from the stone that encased them: “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.” See examples of Flannagan’s work in the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Medellín’s discussion of materials, sincerity, and everyday life is an expression of the direct carving credo. For a treatment of direct carving (though one that omits early U.S. practitioners), see: “Direct Carving,” The Art Story.

After World War II ended, Jerry Bywaters, the Director of the DMFA, invited Medellín to teach sculpture at the museum’s school. Bywaters, a leading Texas regionalist painter, had met Medellín at NTSTC. They formed a close friendship. Medellín taught at the museum for twenty-two years, and he donated his archives to the Bywaters collection at SMU.

Medellín carving Genoveva during “Art in Action,” c. 1948. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art Archives.

Medellín demonstrated woodcarving and plaster casting for the DMFA’s “Art in Action” educational programs. Altogether, Medellín lived in the Dallas area for more than 40 years. His subsequent biography will be taken up in Part 2 of this review.

Works in Wood, Stone, and Terracotta in Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form, Through 1949

Octavio Medellín, “Indian Woman,” 1926, direct carving in red cedar, 14 x 11 1/2 x 12 in., Kirk Hopper Collection. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Indian Woman, the earliest work in the DMA’s exhibition, is rough hewn, with highly pronounced solids and voids. She is rendered in an eccentric, rustic manner. There isn’t anything that seems particularly indigenous about her.

The woman’s head tilts to the right, likely reflecting the curvature of the piece of wood that Medellín selected. The base is more generalized than the head. These features serve to highlight the material — in this case red cedar — from which Indian Woman is carved.

Medellín is pointedly not attempting to create an illusionistic image. Direct carvers shunned the academic tradition and highly polished effects. They instead looked to other practices in archaic, ancient, medieval, tribal, folk, and pre-Hispanic traditions. As a Mexican native, Medellín evidently wanted to connect with indigenous cultures, hence the title of this piece. But, as in this case, Medellín never showed much interest in rendering particular ethnic features.

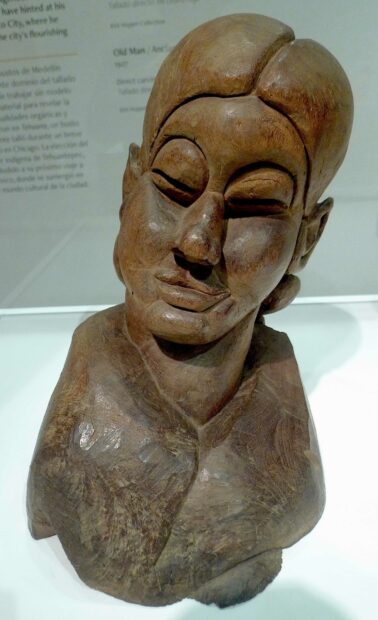

Octavio Medellín, “Old Man,” 1927, direct carving in red cedar, 16 1/4 x 8 x 7 1/4 in., Kirk Hopper Collection. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Medellín’s Old Man again has a face made up of a network of solids and voids. I am reminded of the expression “the bump and hollow,” a phrase coined by the famed regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton (the teacher of Jackson Pollock), who explained his method in articles in Arts magazine in 1926 and 1927. Indian Woman and Old Man are exactly contemporary with Benton’s articles, and possibly reflect familiarity with them.

The base on which Old Man is situated recalls some of the bases Constantine Brancusi (one of the key figures in the history of direct carving) made for his own sculptures. See the round-topped base Brancusi made for L’enfant endormi (1908).

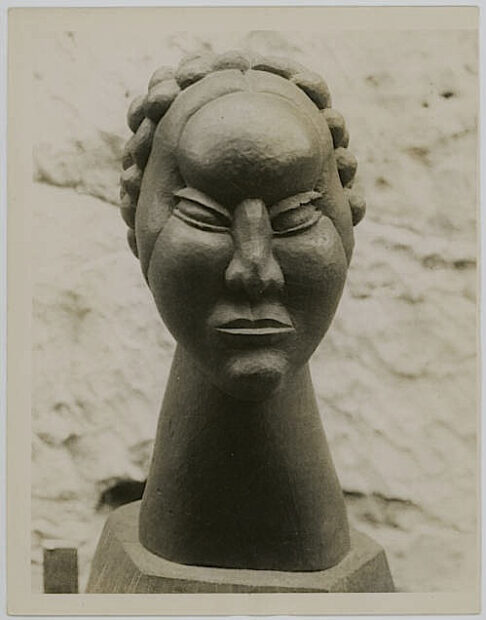

Photograph of “Tehuana” (1928-29) a direct carving in pecan wood by Octavio Medellín, c. 1956, 10 in. high, Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

Medellín’s now lost Tehuana (it is represented in photographic reproduction in the exhibition) reflects a vastly different aesthetic. If Indian Woman and Old Man were rustic, regional, and presented with a heightened foregrounding of their raw materials, Tehuana is more abstract and streamlined, more a reflection of industrial modernity and the abstracting tendencies of many twentieth-century artists.

Tehuana’s base is not part of a gnarled log, nor is it a raw, rough hewn approximation of a Brancusi base. Instead, it is a formidable pyramid of a neck that presents a much more symmetrical face than the two earlier sculptures discussed above. Her forehead is massive, her cheeks are pronounced, and her large nose triangulates into three pronounced sections.

Nonetheless, one can trace a stylistic evolution from one sculpture to another. Firstly, the chin and the lips are rather similar in all three pieces, though the lips become substantially more abstract in Tehuana. Most noticeably, the heads become more frontal. One can even see Tehuana’s base as an abstracting synthesis of Indian Woman and Old Man. One could combine the wide base of Indian Woman, the tall base of Old Man, and whittle this form down to the pyramidal neck of Tehuana.

Women from the isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico were admired for their beauty, exoticism, and independence. A number of important early modern Mexican artists celebrated them, including Diego Rivera in some of his earliest frescoes at the Education Ministry in Mexico City. The colorful Tehuana costumes were also worn by women artists and other members of the modernist intelligentsia in Mexico City, including Frida Kahlo.

Octavio Medellín, “Tehuana” (1928-29), painted or stained pecan wood, image from a slide taken by Medellín, Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

The above image of Tehuana, which was taken in Medellín’s studio, shows that it was coated with dark paint or stain. Since it effaced the character of the wood, this treatment went against the direct carving credo.

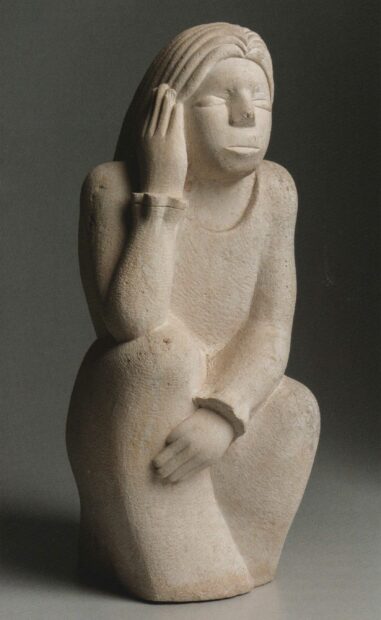

Octavio Medellín, “Thinking Girl,” c. 1930-31, direct carving in limestone, 18 in. (45.7 cm), the Estate of Rena Houston DuBose. Photograph: DMA.

According to the December 28, 1939 San Antonio Light article discussed above, Thinking Girl “was started in1931, after he returned from Mexico. At the time he had a studio over a hen house at 215 Arciniega Street.”

The legs are the best part of Thinking Girl. They are massive, rhythmic forms whose asymmetry creates a sense of dynamism in an otherwise passive, inner-directed, mostly symmetrical figure. Here we can glean the subtle influence of Cubist-inspired sculpture, such as that of Alexander Archipenko, who was another sculptor Medellín admired. The legs make it an interesting sculpture to see in the round.

Octavio Medellín, “Thinking Girl,” c. 1930-31, direct carving in limestone, 18 in. (45.7 cm), the Estate of Rena Houston DuBose. Photograph: Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

The above photograph is from a slide taken by Medellín when the statue was outside.

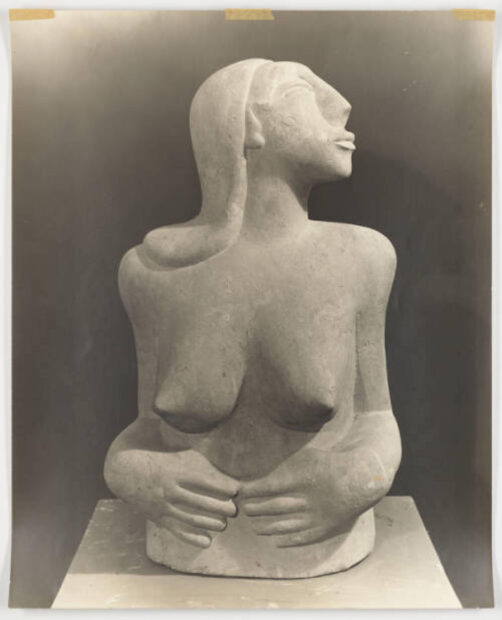

Photograph of “Primitive Woman” (c. 1931-35), c. 1956, 20 in. high, Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

Castro notes that the now-lost Primitive Woman (represented in the exhibition by photographic reproduction) was featured in several early exhibitions of Medellín’s work. As Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighton point out, the term “primitive” was part of a binary opposition to “civilized.” In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many artists sought to “celebrate features of the art and cultures of people deemed ‘primitive’ and to appropriate their supposed simplicity and authenticity to the project of transforming Western art…” (Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighton, “Primitive,” in Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff, eds., Critical Terms for Art History, University of Chicago Press, 1996).

The cultures that produced direct carving (enumerated above) were placed into the primitive category, in opposition to the “civilized” practices of the academic tradition of sculpture. The modernist artists who emulated the works produced by these cultures — in subject matter and/or technique — were often referred to as primitivist artists.

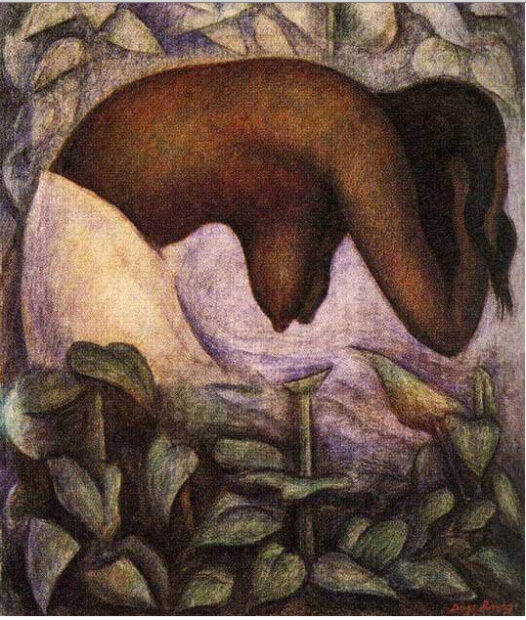

In Primitive Woman, Medellín was self-consciously drawing on the work of modern primitivist artists. Medellín had certainly seen Rivera’s fresco panel Tehuantepec Bathers, painted in the Education Ministry in 1923. Charlot would have directed him there, since he regarded some of Rivera’s Tehuana panels as perhaps the best frescoes of the early Mexican mural renaissance. Rivera approvingly told acquaintances that Tehuana women unselfconsciously bathed naked in rivers, as in his easel painting Bather of Tehuantepec (1923).

Medellín was himself sometimes described as a “primitive” artist, and his comments reflect the philosophy of modern primitivist artists.

Diego Rivera, “Bather of Tehuantepec” (slightly cropped at top), 1923, oil on canvas, 63 x 52 cm., Museo Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico. Photograph: Diego Rivera Foundation.org.

Medellín may not have been familiar with the easel painting reproduced above, but he would have seen other depictions of Tehuana bathers in simple white skirts by Rivera.

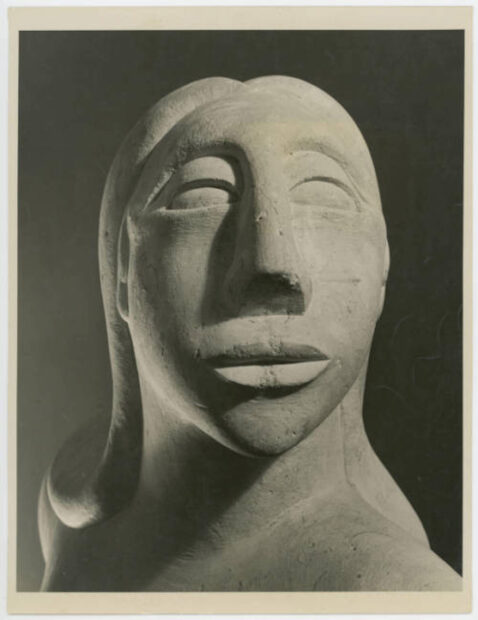

Photograph of “Primitive Woman” (c. 1931-35, detail of head), c. 1956, 20 in. high, Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

Primitive Woman’s head reflects neo-classical influences that were prominent in the 1920s and 1930s. From a frontal view, the head does not look particularly ethnic. Its conjoined forehead and nose hearken back to Indian Woman and Tehuana.

As Castro points out in the catalog, the figure’s nudity is intended to represent “her ‘natural’ state, one that is explicitly tied to Rivera’s bathers, and more subtly in Medellín’s Primitive Woman, to her indigenous identity.”

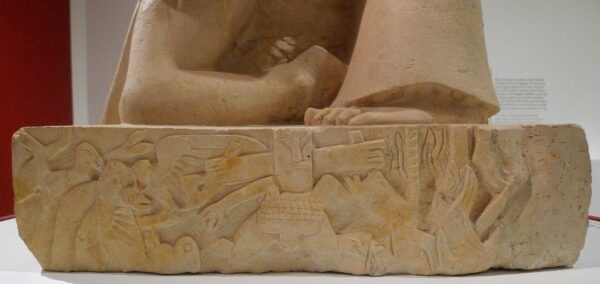

Octavio Medellín, “The Spirit of Revolution,” 1932, direct carving in Texas limestone, 33 1/4 × 16 1/4 × 20 in. (84.46 × 41.28 × 50.8 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Dallas Museum of Art.

The Spirit of Revolution is Medellín’s most eccentric sculpture, and one of his very best. The primary interpretive document for this fascinating work is a letter Medellín wrote to art historian James Oles on August 10, 1992. In his letter to Medellín of July 21, 1992, Oles wrote “any recollections you have about the creation of this work, including a discussion of the relief carving on the base, would be much appreciated” (both letters are in the Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín).

Unfortunately, in some respects, Medellín’s response is almost as cryptic as his figures in the statue. But, through analysis of his letter to Oles, the title, and the sculpture itself, the artist’s intentions can be teased out, nonetheless.

Medellín’s explanation to Oles consists of two sentences. Castro quotes both of them in the catalog. In his first sentence, Medellín states: “The Spirit of the Revolution may be taken politically; however, [it] is pure and simple recollections of personal experiences of [a] time, spontaneously carved directly in to the stone.” We are on safe ground looking at this painting in political terms. As noted above, Medellín witnessed aspects of the Mexican Revolution, and he also was aware of the widespread violence that took place over a course of many years. In the above passage, he emphasizes the personal nature of this work, as well as the fact that it was carved directly. Medellín utilizes Ole’s term “recollections,” and he specifies that they are of a “pure and simple” nature.

The second germane sentence in Medellín’s letter to Oles states:

Like a metamorphosis of form coming from within, it represents the image of a people in a tragic outcry for freedom, [from] oppression and existence; in a fighting revolt inflicted by foreign influences and the power of the christian religion, against forces and spirit of their heritage.

Medellín does not specifically identify the statue’s figures. Nor does he discuss the relief carvings on the base.

Octavio Medellín, “The Spirit of Revolution,” 1932, direct carving in Texas limestone, 33 1/4 × 16 1/4 × 20 in. (84.46 × 41.28 × 50.8 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The soldier on his knees in the foreground issues a cry for freedom against the “oppression” of reactionary forces. He could be singing or shouting “¡Viva la Revolución!” Since the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz served foreign interests and was allied with the Catholic Church hierarchy, we can take these as the enemies of the people specified by Medellín.

The woman standing behind the soldier has been interpreted as a representation of the Catholic Church, as noted by Castro in the catalog. But is she not more likely to be an allegorical figure of the people, rather than the church? After all, this piece is called The Spirit of Revolution, not Revolution and Counter-Revolution.

This symbolic mother is in the act of blessing her son, and, by extension, the revolution. There is no reason for the church to be represented explicitly in sculptural form. Porfirio Díaz and foreign interests are likewise unrepresented. They are not part of the spirit of the people. They are the people’s antagonists.

If she were meant to be the church, why is this woman topless — such a representation would be absolutely anathema to the Catholic Church and conventional iconography. Even a low-cut blouse would be regarded by the church as highly objectionable. Her simple skirt is very similar to those worn by Rivera’s Tehuana bathers, such as the one illustrated above.

Symbolic and exemplary Catholic female figures, like the Virgin Mary, are always covered in layers of clothing. One rarely sees more than their face and hands. They have their hair appropriately covered — they do not sport bouncy, bouffant hairdos that terminate in braids, which are an attribute of indigenous women. Finally, this woman bears absolutely no emblem or symbol of the church, such as a cross or a rosary.

Instead, this figure’s bare breasts are her symbol. They represent her physically nurturing role as a mother to the soldier, and hence as a mother to the revolution. Eugéne Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) features a bare-breasted allegorical woman who supports armed political revolution. Delacroix’s painting is quite possibly a source for Medellín’s bare-breasted female figure.

Unlike Delacroix’s figure of liberty, which storms the barricade while wielding the French tricolor flag, Medellín’s female figure instead blesses the young soldier before he departs for battle — and perhaps the blessing is meant to continue while he is in active service. In performing this function, she is like the mother in Ester Hernández’s La Última Benedicíon de Soldier Boy (1991, illustrated in Art of the Other Mexico: Sources and Meanings, The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, 1993). Hernández’s pastel features a uniformed soldier on his knees, facing his clothed mother. She stands above him, with her left hand on his right shoulder and her right hand partially raised in a gesture of benediction. Medellín’s figure, on the other hand, is topless because, like the snake, she is an allegorical figure. The soldier and the topless woman are not meant to be physically present in any given time or place.

Octavio Medellín, “The Spirit of Revolution” (detail of serpent suckling bare-breasted woman) 1932, direct carving in Texas limestone, 33 1/4 × 16 1/4 × 20 in. (84.46 × 41.28 × 50.8 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The most perplexing element in The Spirit of Revolution is the serpent that is coiled between the soldier and the bare-breasted woman. The standard interpretation has it biting the left breast of the woman (ie. the Catholic Church in the standard interpretation). Castro, on the other hand, proposes that the snake could be nursing from the allegorical woman, “raising questions of how Mexico’s ancient traditions and Christian heritage have over time become symbiotically intertwined.” I think Castro is right to see the serpent as nursing rather than biting.

But I don’t think Castro’s conclusion is in agreement with Medellín’s explanation of the sculpture, or with his title. Why would the church be blessing an anti-clerical revolution? And why would it be nurturing a serpent, which, in Christian iconography, is the very symbol of the Devil, and hence of evil itself? Indigenous religions were in fact explicitly linked to the Devil by Catholics in Mexico and Spain, and they were ruthlessly repressed, to a degree that is shocking to modern sensibilities. See my Glasstire article, “Is Day of the Dead More Indigenous or Catholic? Friars Durán and Sahagún vs. Wikipedia.”

Nor would the Catholic Church want its publicly bared breast to be mouthed by a snake (whether biting or suckling). Such imagery would be regarded as supreme blasphemy. I am confident that Medellín did not make a sculpture whose intended meaning would be regarded as blasphemous, abhorrent, and highly inflammatory. So what was his message in this piece?

In my view, the armed man who is shouting or singing as he kneels, the snake, and the bare-breasted woman all represent what Medellín called the “forces and spirit of their heritage.” That spirit is indigenous, righteous, and, in the context of the Mexican Revolution, it is revolutionary. These three figures are allied against “foreign influences and the power of the Christian religion.”

The man is clearly a revolutionary. The woman is behind the man and literally has his back. Castro’s point that the woman is nursing the snake makes more sense if the three figures are allied on the same side, something akin to the “revolutionary trinity” (an expression used to refer to the soldier, worker, and peasant in the context of the Mexican Revolution). The woman should thus be seen as a nurturing mother rather than the Catholic Church. She is, as Castro puts it, “symbiotically” connected to the snake. But the reason for this connection is that the snake represents the people’s ancient indigenous heritage (as Castro notes). The nurturing woman is symbolically the mother, the essence of the people who nurtured the ancients and who likewise nurture the modern revolutionaries, including, as in Medellín’s statue, through the act of blessing. The snake represents not only the spirit of the indigenous past, but also the spirit of the indigenous present.

Octavio Medellín, “The Spirit of Revolution” (detail of relief on the right side of the base), 1932, direct carving in Texas limestone, 33 1/4 × 16 1/4 × 20 in. (84.46 × 41.28 × 50.8 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Additional evidence for my interpretation is found in the two relief carvings on the sides of the statue’s base. On the right side, illustrated above, a bound prisoner is in the center foreground. His head is plunged in water. Judging from his outstretched arms, he is still alive (his proper left forearm and hand are missing due to damage). Behind him, a strange caricature of a person has a stiff, cruciform shape. The meaning of the relief depends upon the identification of this figure, which I return to below.

On the left side of the relief, vultures wait for the man to expire. They were likely inspired by the vultures in Orozco’s frescoes in the former College of San Ildefonso (which became the National Preparatory School). On the right side of the relief, one can see the dangling sandaled feet of a lynched man, as well as a rope that extends to the ground. The sharp, flame-like elements below and to the side of the feet represent flames. The man is simultaneously being hung and burned alive. (No wonder the figure of the topless woman is bestowing a blessing to the soldier.) Given his footwear, this lynched and burning man is a peasant, not a member of the elite, and not a worker or a Federalist soldier, who would be portrayed with shoes or boots.

By implication, the bound man in the center foreground is also a peasant who is being tortured in a rural area. Is the cruciform shape behind the tortured man an anthropomorphized cross, or is it a caricature of a man in a cruciform pose? Given the manner in which some figures are rendered in the relief on the other side of the statue, I see him as a man in a cruciform pose. Specifically, he would be the man who is keeping the bound peasant’s head underwater. This man has a cruciform disposition because he is a right-wing, religious torturer. He — and other men like him — must also be responsible for the lynched and burned peasant on the right, represented by his sandaled feet. These two victims, in turn, stand for an entire class of victims.

Is this a representation of events after the Mexican Revolution has commenced, or is it a prelude to the revolution, one that shows circumstances that contributed to the outbreak of fighting? There is no definitive answer, but I suspect it is likely the latter, especially since there is no evidence of actual combat. In the countryside, the powerful haciendas, which grew in power under Díaz, were expropriating enormous quantities of land, displacing and virtually enslaving the peasants who had worked these plots as ancestral lands for untold generations. The hacendados, the owners of these vastly expanding properties, had almost unlimited power on the land they controlled.

Their abusive behavior was dramatized in Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished film ¡Que Viva Mexico!, which was filmed in 1931-32, making it contemporary with Medellín’s sculpture. (Portions of the film were released in 1933; the best version, edited by one of Eisenstein’s assistants and linked above, was released in 1979.) Near the end of ¡Que Viva Mexico!, bound peasants were buried up to their shoulders. They were then sadistically trampled to death by horses ridden by the hacendados and their henchmen. This harrowing scene symbolizes the brutal and violent practices that sparked the revolution (which was not filmed because Eisenstein’s funding was cut).

With great economy, Medellín depicts similar scenes of deadly torture. His political sympathies are nowhere rendered more explicit than in his relief on the right side of the base. Though he subsequently sculpted a young man tied to a stake (1937-38) and a hanged man (1939), which are discussed below, these figures are lacking historical reference and context. Medellín included other scenes of oppression in his History of Mexico (1950, to be discussed in Part Two) including a man hanging in proximity to a church. Fortunately we have insight into the meaning of this scene in the form of an objection raised by Frank Paxton, who commissioned this sculpture. In a letter to Medellín dated July 12, 1949, which Castro quotes in the catalog, Paxton declares:

An afterthought I have had with regard to the one scene, i.e., the conversion of the Indians to Christianity, I believe we will omit that part where they tortured them. In other words, if they didn’t acknowledge Christianity, they hanged them. No doubt that is true, but some people may resent being reminded thereof.

Castro also paraphrases a section of Medellín’s unfinished autobiographical text: “… he describes the aim of improving the life of the poor as a just cause for the ‘Revolution’ but explains hat it nevertheless led to many innocent people being ‘killed and hanged.’” Medellin thus emphasizes that his sympathies are with the poor and against the elites who have oppressed them.

For a concise discussion of the connection between powerful haciendas and the Mexican Revolution, see Milagro’s “Study Guide: The Hacienda System and the Mexican Revolution.” Also see “Land, Liberty, and the Mexican Revolution,” which also discusses how Díaz favored foreign interests.

Octavio Medellín, “The Spirit of Revolution” (left side of the statue, including the base), 1932, direct carving in Texas limestone, 33 1/4 × 16 1/4 × 20 in. (84.46 × 41.28 × 50.8 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The two relief carvings on the base of The Spirit of the Revolution have to be read in tandem, so we turn now to the other relief. Two of the three vignettes on the relief on the left side of the statue’s base are easy to read. The stylized birds on the far left of the base are doves, symbolizing a time of peace. They are the antithesis of the buzzards on the other side of the statue. The latter feed on the bodies left by the murderous hacendados, or on the corpses that, for the vultures, are the harvest of war.

In the center of this relief, a woman kisses a man on the top of his head. Before considering its possible significance, we should look at the third scene carved on this relief.

Octavio Medellín, “The Spirit of Revolution” (detail of the base on the left side of the statue) 1932, direct carving in Texas limestone, 33 1/4 × 16 1/4 × 20 in. (84.46 × 41.28 × 50.8 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: scan from a slide taken by Medellín, Courtesy of Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University.

In the above detail of the rightmost section of the left side of the base, there are two groups of men. A small group of men are in the lower right, and a larger group of men arch above them. Several of these men are in a state of excitation: they have upraised arms with bent elbows. One of these men wears a thin crown.

Octavio Medellín, “Ecce Homo” (detail of head), 1953, terracotta, 43 x 12 ½ x 6 ½ in., collection of Barbara Delabano, Dallas, Texas. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

When we compare this crowned figure to a detail of Medellín’s Ecce Homo (1953), we can see that it represents Christ with his crown of thorns, before his crucifixion. In the upper portion of the scene on the relief, his hands are symbolically affixed to the center of a small cross with a nail.

Christ’s crucifixion — which in its cruelty bears comparison to the torturous and unjust murders of peasants on the other side of the relief — is held by believers to be the supreme sacrifice that enables spiritual redemption. It is thus expected to usher in an age of peace. Doves traditionally symbolize Christianity and the absence of war.

Let us return to the figures of the mother and son in the center of this relief. Given the now very difficult-to-read scene with Christ (which has suffered damage), Medellín might have intended these figures to have a dual function. On the one hand, we can view these two figures as Christ taking leave of his mother. At the same time, we can interpret them as a mother kissing her son after he has returned from battle. These two figures relate directly to the peasant mother and son represented in the sculpture above, though they are “real” and present together at the same point in time, rather than symbolically.

The sacrifice of the men who fought in the Mexican Revolution are not explicitly depicted in the act of fighting anywhere in this sculpture. That is because its subject is the spirit of the revolution, rather than a depiction of the revolution itself. Nonetheless, the soldier with the rifle — who stands for revolutionary soldiers in general — is analogized to Christ’s sacrifice on the cross through the relief on the left side of the base. The soldiers who fought in the revolution likewise risked making the supreme sacrifice.

In chronological terms, the relief with the tortured peasants can be placed before the revolution, the sculpture itself at the opening of the revolution and the onset of armed conflict, and the relief with the mother and son after the revolution. Medellín thus created a rich, unified, and sophisticated work, one that resonates in a manner he could not — or preferred not to — explain in verbal terms.

Diaz, his ministers (los científicos), the hacendados, the Catholic hierarchy and other elites, as well as the revolutionary peasant soldiers all worshiped Christ. But they conceptualized him in vastly different ways — as dissimilar as a contemporary liberation theologist is from a megachurch-prosperity-gospel-evangelical or a MAGA Republican.

A major bifurcation of Marian symbolism took place in Mexico during the War of Independence, which began in 1810. The revolutionary firebrand Padre Hidalgo fought under the banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, while the Spanish utilized the Virgin of Remedios, who they credited with a miraculous intervention during the conquest of the Aztecs. During the struggle for independence, reactionary nuns dressed the Virgin of Remedios in a general’s uniform, and loyalist troops are said to have placed images of the Virgin of Guadalupe on the soles of their shoes in order to abuse and humiliate her. The Virgin Mary was thus split into self-battling images of conquest and liberation. During the Mexican Revolution, the Zapatistas continued the latter tradition by placing an image of Guadalupe in the bands of their large hats.

Judging from his letter to Oles and the objection raised by Paxton, Medellín had considerable antipathy to the church’s official policies at the time of the conquest and at the time of the Mexican Revolution. That, however, did not prevent him from using Christian iconography in a positive manner in The Spirit of the Revolution on one of the relief carvings.

Medellín’s sculpture is deceptively complex and allusive. In his artistic statement for MoMA, Medellín made a connection between “the prehispanic and colonial Indian sculptors” who carved “directly in stone.” He clearly regarded himself as one of their successors.

Octavio Medellín, “Untitled” (Woman Holding a Deer) and “Untitled” (Man with a Sheaf of Wheat), both about 1930-1936, both terracotta, both 17 1.2 x 9 x 6 3/4 in. (44.5 x 22.9 x 17.2 cm), both San Antonio Art Museum, gift of Harding Black in memory of Eleanor Onderdonk. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

This pair of works was made with a plaster mold. Castro notes that two other sets are known and that they evoke Art Deco architectural elements. He also calls attention to a note in a SMU file indicating that they were models for never-completed sculptures at San Antonio’s Majestic Theater. Castro also points out that in 1940, the college newspaper in Denton mentioned “casts… made for niches in a San Antonio Office Building.” Perhaps these references are to related projects. The Handbook of Texas entry on Lucy Maverick (cited above) states: “In the 1930s she designed and supervised the construction of modern furniture, some of which was placed in the Majestic Building offices in San Antonio.” There is a good chance that Maverick also tried to get her protégé involved in this project.

Octavio Medellín, “Untitled” (Woman Holding a Deer), about 1930-1936, terracotta, 17 x 5 1/2 x 8 in. (43.2 x 14 x 20.3 cm), The University Art Collection at Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

This darker variant seems to have a finer finish than the above example in San Antonio.

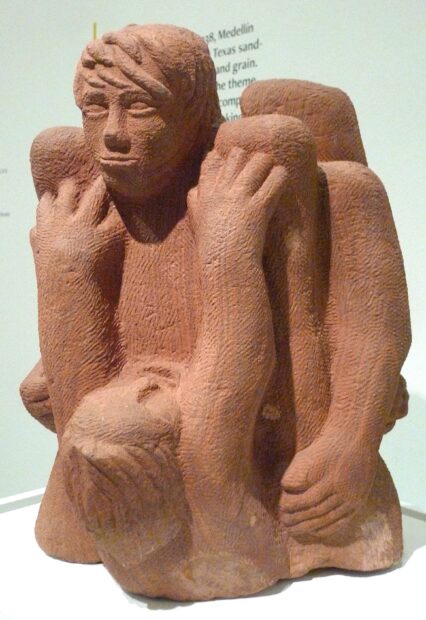

Octavio Medellín, “The Struggle,” 1938, direct carving in red sandstone, 25 5/8 × 13 1/4 × 17 1/2 in. (65.09 × 33.66 × 44.45 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Medellín makes a very unusual family group in The Struggle. It is a statue that has to be seen in the round to be appreciated. (Another view of the statue is visible in the second image of The Spirit of Revolution reproduced above.)

Octavio Medellín, “The Struggle,” 1938, direct carving in red sandstone, 25 5/8 × 13 1/4 × 17 1/2 in. (65.09 × 33.66 × 44.45 cm), lent by the estate of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

From this perspective, one has no sense that the man and the woman are so separated. Medellín liked this red sandstone, which, in his MoMA statement, he compared to petrified wood.

When I saw The Struggle at the DMA, I had the sense that it would work better on a larger scale, so that the individual parts could be viewed more discreetly. In the catalog, Castro notes that the model for a larger group on the same theme had been destroyed while Medellín and his family were in the Yucatán.

Octavio Medellín, “Father and Son,” 1938, direct carving in red sandstone, 38 in. high, collection of Medellín Family. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Castro observes that the kneeling father “evokes the formal symmetry of ancient Mexican sculpture.” Forms rise up from the figure’s compressed knees in a crescendo of interlocking forms that are emphasized by the plumpness of the baby. The man, in fact, would stand alone quite well without the infant.

Octavio Medellín, “Father and Son,” 1938, direct carving in red sandstone, 38 in. high, collection of Medellín Family. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The stone’s beautiful patterns are evident in this detail, as is the degree to which the infant clings to his father with his stubby limbs. Castro notes that when this sculpture was made, “such tender displays of emotion were uncommon for men.”

Zorach’s rounded, abstracted interlocking figures probably inspired Medellín, who likely knew Zorach through Lucy Maverick, who had worked with Zorach in Provincetown, Massachusetts in 1914.

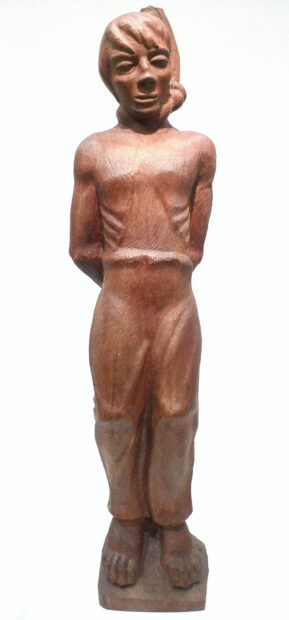

Photograph of “At the Stake” (1937-38) direct carving in red cedar by Octavio Medellín, c. 1956, 20 in. high, Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, Gift of Octavio Medellín.

This bound boy seems to be suffering intense pain. People who are bound for whipping have their backs exposed. Medellín could have felt that it was more dramatic to show the boy’s face than to obscure it, but it is more likely that this unfortunate soul is being burned alive (as in the relief with the hanged peasant on the right side of The Spirit of Revolution’s base). This boy’s body seems to blend into the stake to which he is fastened. I cannot not look at the photograph of this sculpture without imagining flames consuming the figure. This young man could be a victim of the Inquisition (without a conical hat) following the conquest, rather than a victim from the time of the revolution. I hope that this lost sculpture will someday be found.

Octavio Medellín, “The Hanged,” c. 1939, direct carving in black walnut, 42 x 10 1/2 x 10 in. (106.68 x 26.67 x 25.4 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, Kiest Memorial Purchase Prize, Fourteenth Annual Dallas Allied Arts Exhibition, 1943. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Given his incredibly desperate situation, this gaunt young man seems rather calm. His eyes are open and his mouth is twisted to the right; evidently he is resigned to his fate.

From a frontal view, he seems to be sanding on his toes rather than hanging from a rope. (This must be because his body has to be connected to the sculpture’s base through the bottoms of his feet.) The rope should be biting into his neck, and his face should register distress, perhaps bulging eyes, a swollen lower face, a desperately grasping mouth. Thus The Hanged is very unlike many other contemporary depictions of lynching, which emphasize distress and suffering, sometimes with expressionistic frenzy.

Castro points out in the catalogue that when he made this sculpture, Medellín would have been aware of at least some aspects of the history of lynching in Texas.

The NAACP has tallied 4,743 lynchings in the U.S. from 1882 to 1968 (72% of which were done to Black people), with 581 in Mississippi, 531 in Georgia, and 493 in Texas. Evidently, the NAACP’s figure for Texas is a severe undercount.

Lynching in Texas, a new website directed by Jeffrey Littlejohn at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, has documented over 700 lynchings in Texas. This figure includes lynchings of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, which had been severely undercounted, especially when they were perpetrated by Texas Rangers and other law enforcement officials. See Michael Barnes’ discussion in the Austin American-Statesman (January 15, 2021).

Not long before Medellín moved to Dallas, the city had a notorious reputation for racism, which included incidents of mob murder, whippings, and a high number of tarring-and-featherings. After the Dallas Klan chapter was organized in 1920, it reputedly became the largest one in the world within four years, with as many as one out of three eligible Dallas men as members. As D Magazine put it: “And in no other city did the Klan find a readier reception than in Dallas” (Darwin Payne, “When Dallas was the Most Racist City in America,” May 22, 2017). In 1923, the State Fair of Texas even had an official Ku Klux Klan Day, which drew 160,000 people. That evening it held a record public initiation, with 25,000 spectators. The Dallas Morning News waged a campaign against the Klan (in response, the Klan accused the newspaper of being Catholic), and the Klan declined precipitously in the late 1920s.

Octavio Medellín, “The Hanged,” c. 1939, direct carving in black walnut, 42 x 10 1/2 x 10 in. (106.68 x 26.67 x 25.4 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, Kiest Memorial Purchase Prize, Fourteenth Annual Dallas Allied Arts Exhibition, 1943. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

From the side, one gets a sense that the young man’s body is suspended because of the manner in which his knees are bent. But neither the young man’s head nor neck conveys the strain of an actual hanging, when the body’s full weight bears down on the lowest points of the noose.

Nor does the young man seem to be making what would necessarily be desperate efforts to breathe while the rope is crushing down on his windpipe. In sum, this is a curiously sanitized version of a lynching. Of course, if Medellín had sculpted a work that conveyed the full horror of this torturous method of killing, it likely would have disturbed his museum audience, and he perhaps would not have won the Kiest purchase prize. Such a work would likely have been too real, and much too close to home.

Medellín has left patterns of chisel marks that serve to highlight individual planes. When one examines the sculpture close-up, it is much less detailed than it seems to be from a distance.

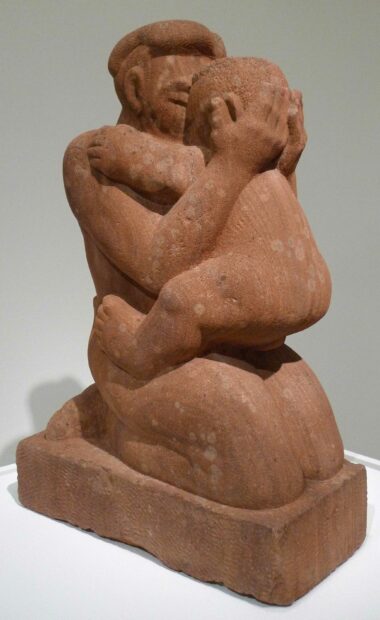

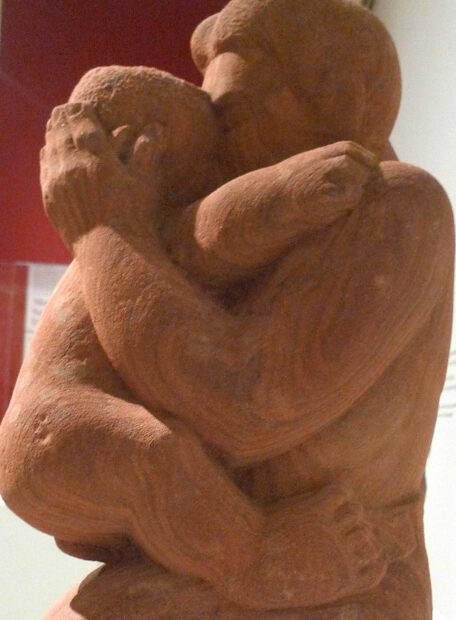

The Penitents is one of Medellín’s finest works. Like The Struggle, it has to be viewed in the round for the work to have its full effect. While The Struggle cultivated roughness of finish and had a rather awkward relationship between the three figures, Medellín has opted for a smooth finish in the mold-made Penitents, and he has created a masterful and emotive relationship between these two figures, which are locked in rhythmically counterpoised paroxysms of self-punishment.

Octavio Medellín, “The Penitents,” 1940, cast stone, 21 1/2 x 14 x 9 3/4 in., collection of L. Simmons. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The compactness of these two forms, and the rhyming parallel bands of hair, whiskers, ribs, and rope, make it a marvel to behold. I walked around The Penitants many times in order to experience how the artist balanced solids and voids.

Octavio Medellín, “Holy Roller,” 1940–1941, terracotta, 19 1/2 x 8 x 9 1/4 in., collection of Medellín Family. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

As Castro notes, Holy Roller embodies an antithetical extreme of religious fervor. If The Penitants is about self-abasement, unworthiness, regret (and probably fear of punishment), Holy Roller is uplifting and ecstatically joyful.

Holy Roller is also very unlike Thinking Girl. The latter is bulky, contemplative, and inner-directed. In Holy Roller, Medellín develops the asymmetry found in Thinking Girl’s knees, and he takes this asymmetry to its logical conclusion: Holy Roller’s left knee is sharply directed upward, while her right knee is on the ground.

Octavio Medellín, “Holy Roller,” 1940–1941, terracotta, 19 1/2 x 8 x 9 1/4 in., collection of Medellín Family. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Medellín also uses the elongation and the elevation of the woman’s arms to powerful effect, as her voice, head, hands, and left knee are directed upward.

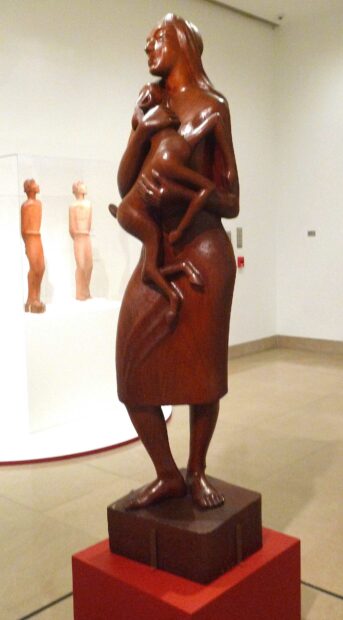

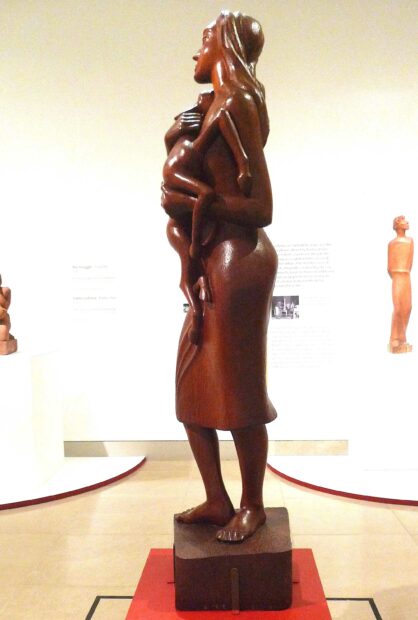

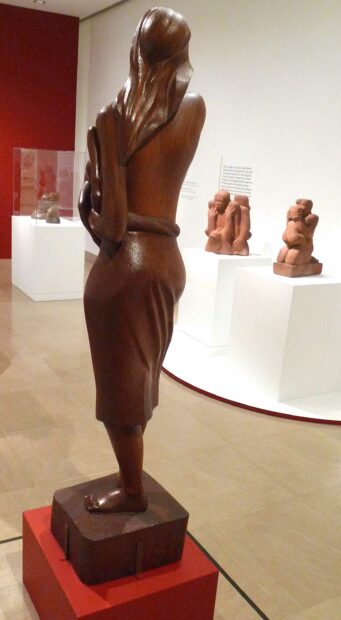

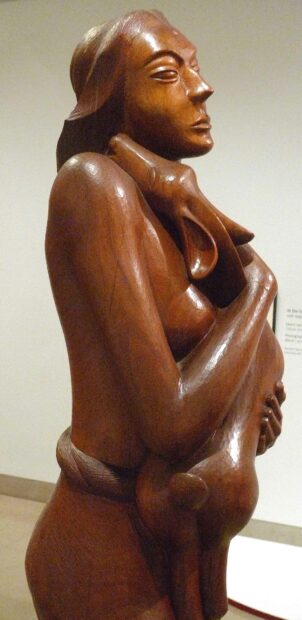

Octavio Medellín, “Genoveva of Brabante,” 1948–1949, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, 7 feet high, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

In 1890 a Kansas City lumberman imported an extraordinary 500-pound log of Honduras red mahogany, intending to have it carved into a statue. His son, Frank Paxton, eventually approached Medellín, who made two remarkable statues from the log.

The first of these was Genoveva of Brabante, based on a tale about a woman wrongly accused of adultery who was saved by a roe deer and who lived in a forest for seven years. (See my review of Meret Oppenheim, a Surrealist artist who treated this subject multiple times.)

Who came up with this subject, the Missouri lumberman or the Texas sculptor? Castro proposes that, due to his love of classical music, Medellín may have been familiar with the story through an opera. In any case, Medellín produced a monumental, highly finished sculpture that he labored over for an estimated 1,120 hours (some of it in public through the DMFA’s “Art in Action” program).

Octavio Medellín, “Genoveva of Brabante,” 1948–1949, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, 7 feet high, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The sculptor did an extraordinary job of conveying Genoveva’s gratitude through the manner in which she presses the deer’s body against her own. The deer, in fact, seems to reciprocate by placing its legs against Genoveva’s body.

Octavio Medellín, “Genoveva of Brabante,” 1948–1949, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, 7 feet high, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

This deceptively simple and very graceful figure has balanced curves and accents that look good from every angle.

Octavio Medellín, “Genoveva of Brabante,” 1948–1949, direct carving in Honduras red mahogany, 7 feet high, Guadalupe Centers, Kansas City, MO, Gift of Frank Paxton, Jr. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The deer snuggles its head against Genoveva’s neck. Looking at this detail, one would think that the woman, a giantess with impossibly long, graceful arms, is saving the deer, rather than vice versa.

Paxton must have been very pleased with his choice of artist, because the other sculpture Medellín carved from the massive mahogany log was his masterpiece, The History of Mexico (1950), with which I will begin Part Two of this review.

***

My thanks to Emily Grubb, who provided me with material from the Bywaters Special Collections, Southern Methodist University, including the Oles-Medellín correspondence. I am also grateful to Kristel Orta-Puente, who provided me with newspaper clippings she used in her M.A. thesis on Medellín (some of which are quoted above). In Part Two, I will discuss the Medellín literature and the ongoing research of scholars such as Orta-Puente.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator who has curated more than 30 exhibitions and who has written or contributed to 19 catalogs and books. He has previously reviewed two exhibitions at the DMA for Glasstire: “To Renew the World: Spirit Lodge and the Looting of the ‘King Tut’s Tomb’ of Oklahoma,” and “Van Gogh’s Symbolic Olive Trees and Landscapes at the Dallas Museum of Art.”

4 comments

Thanks for the very informative article. Even as a devotee of Medellin’s, I had not seen may of the images you used. I hope your article leads your readers going to the DMA to see many of the works you describe in great detail.

Thanks, Scott. I wanted to present as many images as possible of the artist’s work. I had rather limited knowledge of Medellín’s work until I saw the exhibition.

For those who can visit the DMA, I do hope everyone will take the opportunity to see the show, which greatly exceeded my expectations.

Fascinating article – thank you for such a thoughtful, in-depth discussion of Medellín’s work. Looking forward to Part II!

Thanks, Sarah. I’m glad you enjoyed the review. I’m hoping to get more of the literature and some more documents before I publish part 2.