Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

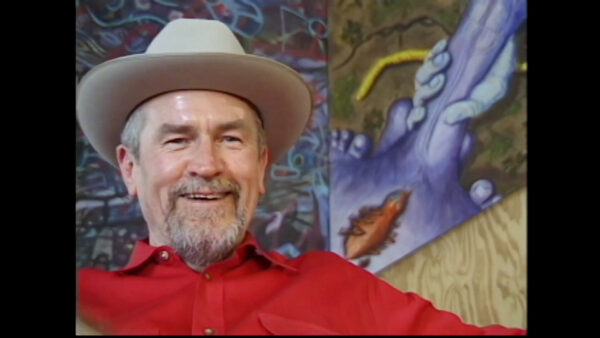

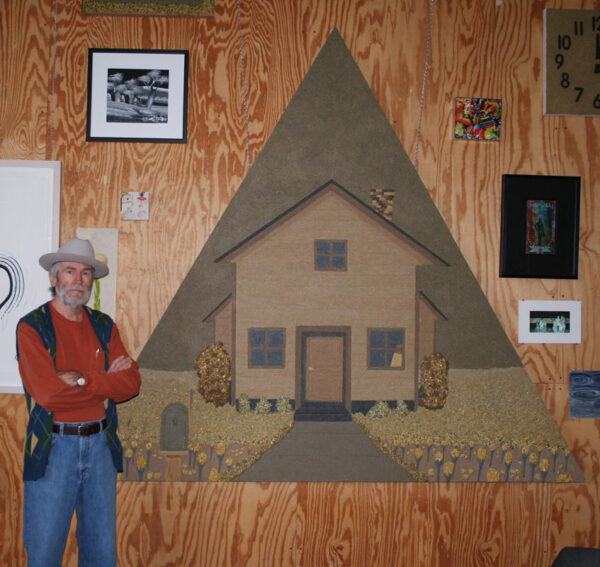

Wayne Gilbert was one of the most punk rock people in Houston’s art scene. On an initial meeting, this wouldn’t come across. His appearance — that of a rather clean cut late middle aged businessman — was deceptive, as was his incisive wit, intelligence, and humor. For years he wore a hat, an off-white, almost manila Stetson, and until the end of his life he spoke with a bit of a drawl that was completely sincere. Wayne (it feels wrong to address him as “Gilbert” here; to everyone, he was Wayne), to use an overextended metaphor, was an onion: you saw the surface, but the second you started to peel back the layers of his intentions, you realized there was much more than met the eye.

When considering his personality and his art, it makes sense that Texas, Houston specifically, was Wayne’s native habitat. His artwork has the rough and tumble fuck-you-ness of a city with no zoning laws, a city that was for years (and maybe still is) on the art world periphery. In many ways, the expanse of Houston has meant that artists here don’t need to be market darlings; because there is affordable space and a fairly accepting public, anyone with a harebrained idea and some chutzpah can attract an audience. Wayne, however, miraculously found a way to create art that was hard for even Houstonians to stomach, art that often got him pushed to the periphery of the periphery, a no man’s land of both market and public neglect in which, strangely enough, he seemed to find solace. More on that in a second.

One of the things that made Wayne punk rock is that he had a compulsion to create a space for the outliers, for the people not represented in Houston’s more conservative and traditional (read: sales-focused) gallery scene. For years, and at a great expense to himself, he operated Gallery 101 and then G Gallery, which he later rechristened the G Spot Contemporary. At the time, I asked Wayne about the name change. He said he finally decided he didn’t care if the name offended people or turned them off. He had always wanted it as his gallery’s name, and, while seeming to acknowledge the term’s sexual overtone, was adamant that the letter represented his last name.

Programming at the gallery was seemingly random, with a nonlinear but distinct theme guiding its methodology — Wayne would host repeat shows for select artists, many of whom created work edging toward the controversial. In some ways he was a (undersung) peer of Jim and Ann Harithas, who championed difficult art with their Houston space, the Station Museum of Contemporary Art. (The Station exhibited Wayne’s work on at least one occasion.) At the same time, G Spot would show established Houston artists, some of whom didn’t make the most salable work, and some who made small-scale work at affordable prices. Since the shows changed out once a month, there was always something new to see, and the Spot (as Wayne would call it) became a sort of meeting ground that crossed boundaries of high and low, known and unknown.

In many ways, Wayne was an art pluralist. He was a supporter of the idea that if art is happening, no matter what it was or who made it, it was worth considering and engaging with. And, based on his exhibitions and who he surrounded himself with, it was clear that he was always championing the underdog, the artist whose work would likely never sell, the artist ignored by everyone else. His admiration for art and artists wasn’t the same as that of gallerists trying to prove the pedigree of their stable (G Spot didn’t represent anyone), and it wasn’t ever exceedingly praising or overwrought. Instead, Wayne was always able to cut to the core of what he thought about something.

Wayne Gilbert in “Rubber: An Art Mob,” Ramzy Telley’s 2000 documentary. Watch it here.

Wayne, like so many of the Houston curators and artists who have died in recent years, was a scene-maker. I’ll argue this until I’m blue in the face, namely because I’m unsure if Houston’s art scene realizes the extent to which he was. He wasn’t as flashy and didn’t have as deep a history as the Harithases; he didn’t collect and then donate art in the same way Clint Willour did (though he did constantly buy and trade work from and with his artist friends); and he didn’t co-found a now-famous nonprofit like Jesse Lott. His moves were quieter: the co-founding of the Rubber Group, a no-holds-barred art and performance collective; his AA group, which for years he hosted at the Spot and was a community for many in and out of the art world; the gallery itself, which showed, according to its website, at minimum 75 artists, and likely many, many more.

A good scene-maker shares what they’re excited about. Years ago, I was one of the many people Wayne took to see the compound of then-83-year-old Leandra Di Buelna. This was before the gallery’s first exhibition with the artist and before Molly Glentzer’s Houston Chronicle article about his life and work. As we walked through Buelna’s house and studio, filled with trinkets, toys, and other inspirations, I could feel Wayne’s excitement for sharing the work. He hoped that, maybe, he could help an unknown artist reach a zenith and an audience that they didn’t know existed. I’m completely convinced that Glentzer’s article wouldn’t have happened without Wayne, and also that he is the sole reason anyone knows about Buelna’s trippy paintings.

I’m convinced that Wayne’s compulsion to promote other unknowns came, at least in a small part, from a desire for his own work to be better understood. He wasn’t a fierce advocate for himself; he didn’t boast and he didn’t hit you over the head with his artwork (though there were inevitably a few of his pieces in the back room of G Spot). But he did believe his work was important, despite never getting the institutional or wider recognition he truly wanted or deserved.

Wayne is punk rock because he managed to create some of the most unique art I have ever seen. This isn’t an exaggeration — in a world saturated with art, where swaths of artists mine near-similar concepts and make indistinguishable work, Wayne found a way of creating, and perhaps more amazingly, an artistic medium, that I had never seen before. In my years visiting with artists, I don’t think I have ever met one who was so quietly passionate about both their work and their craft.

It will forever be a regret of mine that Glasstire never published an in-depth interview with or feature profile of Wayne during his lifetime. I can think of no better (or more fascinating) artist or arts advocate that had spent so many under-recognized years in the trenches, toiling to make Houston’s art scene into what it is today. So here, if you’ll stick with me, I’ll finally spill some ink, correct the record, or, let’s just simply say write, about what Wayne was getting at.

Wayne Gilbert, “Anna D,” 1998, human cremated remains on canvas. This work was made using the first remains Gilbert acquired.

Wayne’s artwork is made using unclaimed cremated remains. Because of the work’s material, it often falls into a trap: to most people, the paintings are never more than the sum of their parts. Classic reactions include: disgust, confusion, repulsion. How could anyone make art with the unclaimed remains of a person? How did Wayne even acquire such a large quantity of human remains? This last question inevitably came about because most of his pieces aren’t small — Wayne wasn’t working at a domestic scale. Instead, he was making statement works, museum-quality, large-scale paintings that he felt demanded attention beyond the standard neck snapping and the open mouthed gape reactions to his materials. Wayne was making art.

It’s unfortunate that this aversion to his medium — a barrier that, upon further reflection makes little sense — prevented so many people from engaging with what Wayne was laying down. I remember when I first heard (from a friend) about Wayne’s chosen artistic medium. If memory serves, the person told me about it a little flippantly, as if the work could be dismissed because of it — either as hokey, gross, or some combination thereof. I remember not feeling one way or another about the fact that Wayne was using cremated remains; instead, I wanted to know what he was about, what brought him to this way of working. If it was a gimmick, it would be obvious; if it was an ineffable passion, the sincerity would come through. Of course, upon meeting the man, I quickly realized it was the latter.

The roughness of Wayne’s work matched up with the personality of his city. In a metropolis with no rules, it only makes sense that someone would find a way to create art using the last possible thing many of us would ever think of. It was important to Wayne that the remains were unclaimed. He was dignifying people as people, people as worthy, an inherently radical and political statement on its own, no matter the artwork’s visual content. To Wayne, this idea was more important than commercial or personal recognition, more important than sales or fame, which is why he kept going long after he realized his chosen medium would inhibit it all.

To this point, Wayne was a conceptualist at heart. The cremains weren’t a schtick or a gag, or a way for him to edge into the conversation. At the same time, they always overshadowed any analysis. His painting, his craft, was good, sometimes great. In his final show, the aptly titled Tomorrow’s Unknown, which opened in July and was on view through last weekend at Redbud Arts Center, each work was a knockout.

There were pure paintings, which showed his skill with traditional mediums — he worked in oil, and when he was on, he was on. There were pieces in which he painted atop ashes, using the remains as a base or as a detail within the work. These pieces, while still maybe inflammatory by traditional mores, are disguised, a more palatable version of the art Wayne was known to make. Still, they are exceedingly impressive — the brightness of his colors, a palette that is definitely not straight out of the tube, contrasts with the ashes to highlight his subjects. The remains, strangely enough, give his paintings life; the works tend to focus on hope, growth, reflection, and opportunity rather than any sort of doom and gloom.

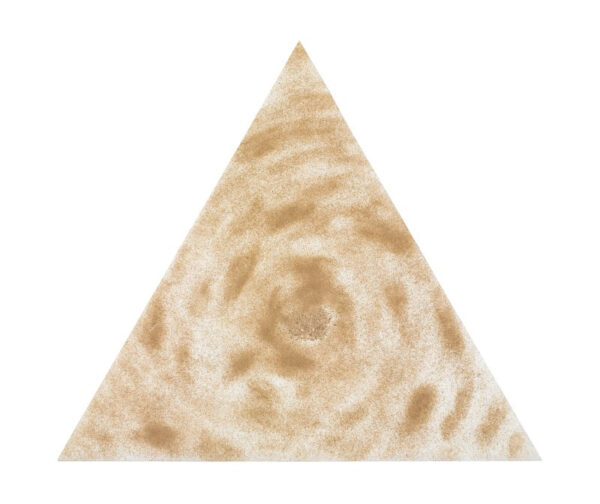

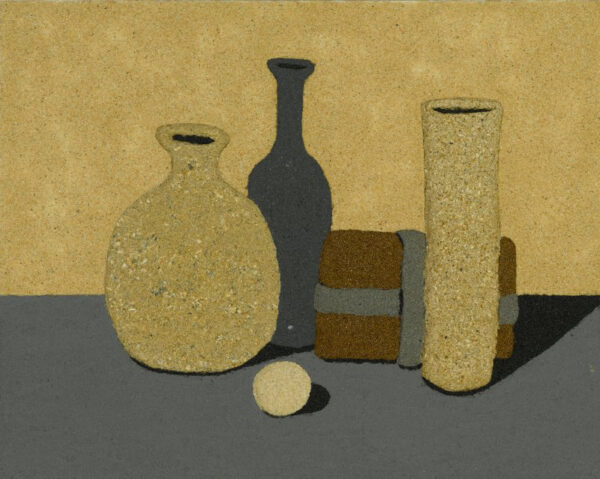

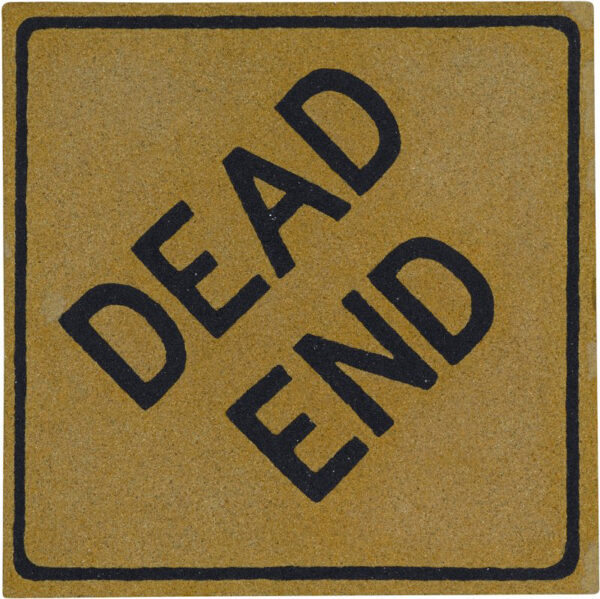

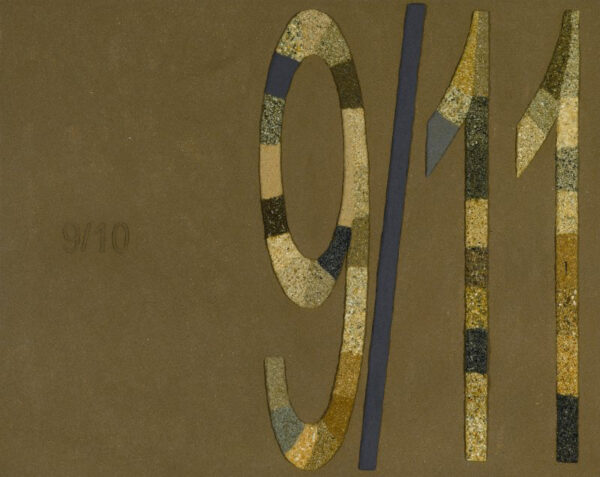

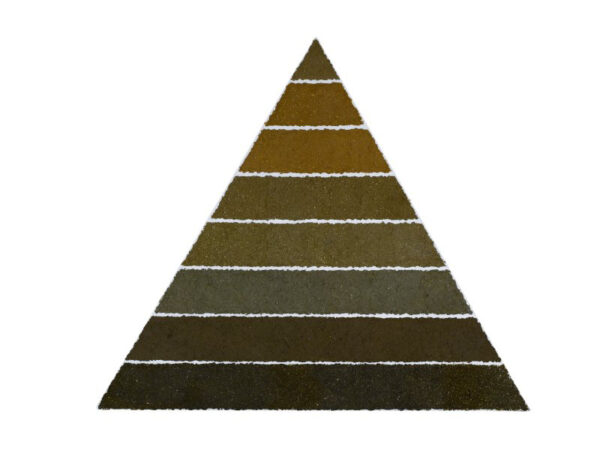

And then there are the pure ash paintings, which have always been my favorite. Wayne commonly talked about how different people’s cremated remains come in different colors. This results in a diverse but monochromatic palette for these works. In them there’s humor — a McDonald’s logo on a nearly black background, faux traffic signs reading “rough road” and “dead end”; but also quiet contemplation — a recreation of a Giorgio Morandi painting titled People in the Manner of Giorgio Morandi. There are also pieces that sit somewhere in-between: a sandy surface framed with bone fragments, titled Minimal Person, and a large triangular work called 8 of My Friends, featuring large, horizontal stripes of what we can assume are individual people’s cremains.

All of these paintings prompt more questions and assumptions than answers: is the McDonald’s logo actually a harsh critique of a food and a chain that contributes to heart disease, one of the leading causes of death in America? Are the traffic signs warnings, either for us or for Wayne himself, that the end is near, a reminder to live life to the fullest? Is Minimal Person a humorous take on the fact that we’re all going to turn to dust, eventually, or is it a serious consideration and addition to or critique of the coldness of the minimalist movement? Is 8 of My Friends a tongue-in-cheek comment on how we are merely people cohabitating the planet, and we shouldn’t be so divided because we all have more in common than we realize? (I do believe, for what it’s worth, that Wayne would have been friends with these eight people, whoever they were.)

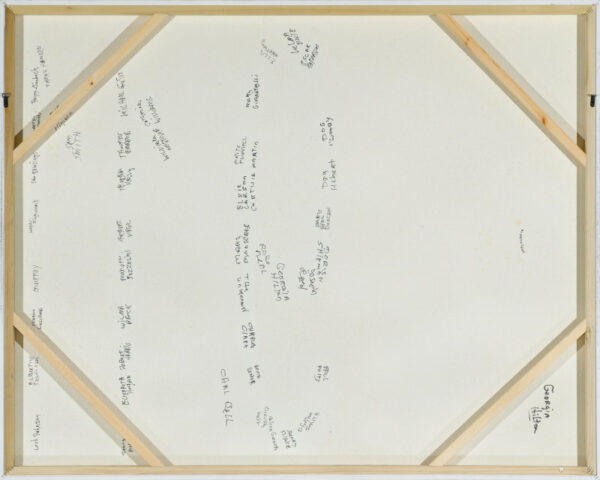

Wayne Gilbert, “The Difference a Day Makes,” 2002, human cremated remains on canvas (back). Gilbert inscribed the back of the painting with the names of the people whose ashes are used in it.

There aren’t any clear or “right” answers to these questions. Wayne’s art is inherently personal, both to him and to any viewer that seriously considers it. His conceptual underpinning extends further, too, to the physicality of the work itself: on the back of each piece, he writes the names of the people featured in the painting. It’s an in memoriam, a dedication, a remembrance, a thank you to those who made the work possible.

My favorite — and I think the best — work I have ever seen by Wayne was proudly displayed in the Redbud show. The painting, Stars and Stripes Forever, is a cremains-only piece made early on, in 2000. (By Wayne’s account, he began making art using human remains in 1998.) The work is a portrait of America, by an American, and made (presumably) of Americans. It is an anonymous but ubiquitous image of the country — Wayne’s country, our country. More poignantly, it is a portrait made of people who were, likely, the least-loved or understood by the country or their kin — folks whose remains were left at a funeral home after their deaths. But because we don’t know who these people were, they are a stand-in for us all. This painting was just as punk rock in 2000 (and is still today) as Jasper Johns’ flag 45 years before. It, like all of Wayne’s work, sits in a gray area of contradiction; it isn’t afraid to get messy, to say what it means, or to be misinterpreted. It embraces duality, because the work, like us, is human and fallible.

I admire Wayne for all he was; it takes a strong conviction (or a stubbornness — Wayne had both) to make art that you know will not be as palatable or recognized as you think it should, but to decide to forge ahead and change nothing. I believe he was bolstered by the fact that those who got his work would appreciate it for all it was worth and more; for him, that was enough.

What artists want is to communicate their passion and vision with the world, to connect with like-minded people while changing perceptions and misheld ideas. I know Wayne did this more than once: a friend told me that although they wanted to dislike Wayne or find a reason to dismiss him and his work, he was always so exceptionally kind, generous, and persistent that they couldn’t help but develop a soft spot for him. I think this is the perfect example — and exactly what he was going for — with both his art and life.

Wayne was a treasure. I’m hard-pressed to think that Houston will ever again have someone so singular, someone who believes so genuinely in the power and talent of artists. He made things happen — albeit quietly and in the background — but this was how he worked anyway; he was used to it. Wayne was someone who didn’t do it for the praise or the glory or the attention. He did it because he needed to, because he felt that the community deserved something more. Because it was who he was. Houston’s community, whether it realizes it or not, has lost a giant.

Update September 4, 2023: There will be a celebration of life for Wayne Gilbert on Sunday, October 15, 2023 at 2 p.m. at The Heights Theater.

6 comments

Thank you for the wonderful remembrance of Wayne and his art, Brandon! At the risk of coming off as self-promoting, I will mention that my forthcoming book from Texas A&M University Press (Dreams, Visions, Other Worlds: Interviews with Texas Artists) includes interviews with both Wayne and Leo di Buelna, to whom Wayne introduced me. Wayne’s interview will be accompanied by “People in the Manner of Giorgio Morandi.” The book is still perhaps a year from publication.

Great article

This is a really wonderful article about his art and more importantly, about the man.

Thank you.

Wayne told me he never felt respected for his work as an artist in Houston. In New York, where he recently was exhibited, he said people treated him very differently, like a real artist. With that validation, and his final Redbud show, I think he went out on a real high. Thank you for writing this, Brendan. Houston will never be the same

So typical that this Texas treasure passed relatively unknown and unappreciated. I am ashamed to admit, this is the first I’ve heard of him. Born in Dallas, grew up in San Antonio, co-founder of SAMOMA, the first artist run art gallery in San Antonio, 1976-79, Wayne Gilbert would have been given a retrospective at our space had we known him. His G Spot gallery and punk aesthetic is a first cousin to our space. I am so pissed at myself for not knowing him personally. Texas is so damn big but the art world is so very small, especially the one that truly matters. I wish I had found your G Spot. R.I.P. Wayne

A true Texas treasure turning ashes into jewels. Great article about a great artist and champion of the arts. Was happy to call him a friend.