Paintings by Ricardo Islas, Brandon Maldonado, and Vicente Telles. Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations are courtesy of the artists and Presa House.

Crossing Borders: Tres de Oeste featured recent work by three powerful and very different Southwestern artists at Presa House Gallery in San Antonio. Two of them, Vicente Telles (b. 1983) and Brandon Maldonado (b. 1980), are based in New Mexico; Ricardo Islas (b. 1970) works in San Diego. The three artists know one another, though this was the first time all three have exhibited together. Telles proposed the exhibition, and the artists selected their own works for Presa House’s show.

Maldonado’s work at Presa House is a departure from his long standing engagement with graffiti and graphic novel traditions. His deepest reference at the moment is traditional New Mexican religious art (also called folk art, santero art, or Spanish colonial art). To this base, he has applied Picassoid heads and linear patterns inspired by the astonishing self-taught artist Martín Ramírez. Maldonado has largely turned away from social concerns to emphasize the formal qualities of his work.

Telles, on the other hand, has been deeply involved with New Mexican religious art (both traditional and contemporary) for many years. But in his work at Presa House, he has — with one important exception — eschewed religious art traditions to explore issues pertaining to Latino emigration and labor. Consequently, both New Mexican artists are presenting uncharacteristic work.

Islas’ work is politically charged, though the ostensible subjects of his work, which include toys, games, and other aspects of popular culture, can be deceptive at first glance. Paintings by the three artists were mixed throughout the rooms at the gallery. In this review I treat the work of the three artists separately.

Brandon Maldonado

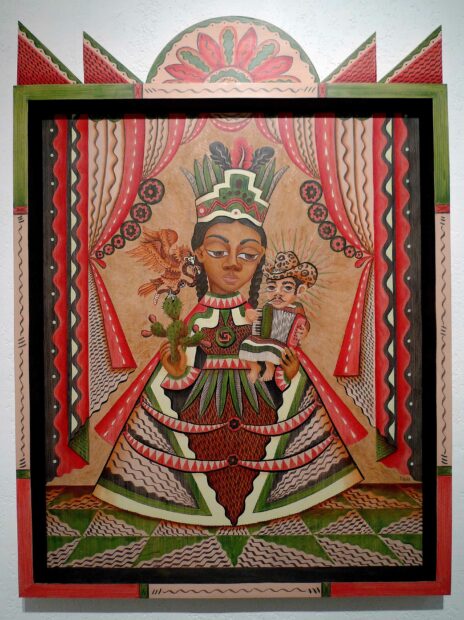

Brandon Maldonado, “Birth of the Mexican, # 2 (Single Mother with Child),” 2022, mixed media on panel, 36 x 30 inches. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Born in 1980 in Denver, Colorado, Brandon Maldonado was raised in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he found artistic inspiration in the graffiti art of his barrio. Primarily a self-taught artist, Maldonado has a BA Humanities degree from the College of Santa Fe. The works at Presa House are rooted in the graphic drawings he made in the 2000s. They feature simplified forms “with mesmerizing, repetitive patterns” inspired by the sources noted above. Maldonado explains his decision to focus on formal issues in this body of work:

I’ve dwelt on a lot of historical / social commentary-themed pieces in the past several years but, with the darkness of the pandemic I just wanted to focus on mark making and primarily painting things that make me feel good and or are funny.

Birth of the Mexican, #2 is one of two paintings in the exhibition (along with St. Rita) without Picassoid heads. They are the closest to New Mexican folk art. Whereas earlier generations of New Mexicans often identified as “Spanish” and denied their indigenous heritage, Maldonado here reacts against the opposite tendency in this painting. He describes it as “mocking those who refuse to recognize the aspect of Mexican culture that came from the Spanish.” The red, green, and white colors reflect the Mexican flag.

Maldonado creates a syncretic, secular image. He utilizes the traditional format of Christian religious painting, but instead of a Europeanized mother and child (Mary and Jesus), he creates a dark-skinned woman with braided hair. She has a feathered headdress and feather ornaments, as well as a medallion with the xicalcoliuhqui (stepped fret) design. The medallion was inspired by a gold and turquoise Mixtec jewel depicting a shield that was found in Yanhuitlan, Oaxaca. (Another painting in the exhibition, Girl of the Sun, features many variations on the stepped fret design in the background, as well as other indigenous patterns.) The Mexican woman holds an eagle on a cactus (the symbol of Mexico) in one hand, and a small man with a cowboy hat and accordion (a type found in curio shops on both sides of the border). The small man’s secular attributes emphasize that he is not a sacred figure.

Chimayó, the site of an adobe chapel in Northern New Mexico that was completed by 1816, is one of the most important religious pilgrimage sites in the U.S.

The late George Kubler preferred the term “folk art” to designate the body of religious work from this period:

Thus folk art can be interpreted as an expression of the brief release, lasting about a century, between two forms of exploitation: agrarian feudalism in the eighteenth century and industrial mass production at the end of the nineteenth. Folk art occupies the brief interval between court taste and commercial taste (Santos, An Exhibition of the Religious Folk Art of New Mexico, Fort Worth, Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1964).

Kubler always takes a long view of things — as those who have read his book The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (Yale, 1962) already know. He comes to an extraordinary conclusion in his Santos catalog essay:

New Mexico after 1750 and until about 1900 was not only the end of the geographic line but it was also the last recipient of the accumulated traditions of Christian imagery. Such a terminal position in space and in time deserves our close attention, for it seems to mark the end of a world of religious expression that opened with the Middle Ages more than a thousand years ago. In the twentieth century, another art has taken form to clothe the old meanings of Christianity, and it is likely that the santeros of New Mexico were the last exponents of the prior tradition.

Since they were far removed from dominating metropolitan centers, artistic prototypes, and ecclesiastical authorities, Kubler notes that these isolated santeros “were free to invent and make simple things for their own pleasure,” resulting in archaic, unique, and unmistakable art that lasted until the imposition of “the new tyranny of industrial production.”

One can see a close connection between the schematic forms in the altar from Chimayó illustrated above — especially the alternating straight and curving lines found in this altarpiece — and the linear patterns in Maldonado’s Birth of the Mexican, #2.

Maldonado has studied the “visual language of the old santeros” during the past year, and he discovered that “there is a lot that can be learned from them” in terms of “their approach to line, weight, loose expressive strokes, abstraction of form, and their visual language.” He soon realized: “there is a natural dialog between the classical period santeros, Martín Ramírez and my own older work.”

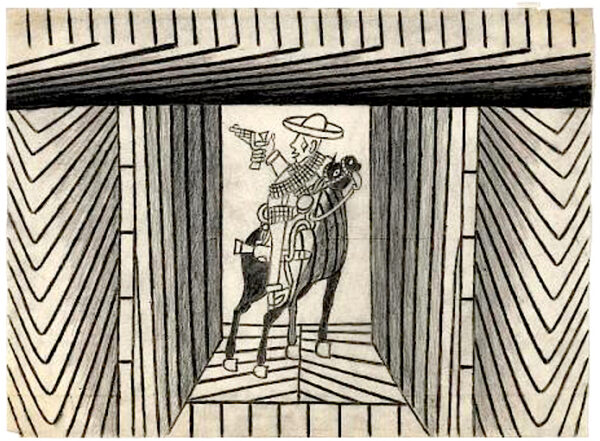

Martín Ramírez (b. 1895, Jalisco, Mexico; d. 1963, Auburn, California), “Untitled (Black and White Caballero # 7),” 1950–55, graphite and tempera on paper, 17 1/2 x 23 3/4 inches, Williams College Museum of Art. Photo: Williams College Museum of Art.

Ramírez has long been categorized as an “outsider artist,” a dubious, ahistorical grab-all category for variously marginalized artists. Víctor M. Espinosa undertook long-term research to historicize Ramírez’s work. See Edward M. Gómez’s review of Espinosa’s Martín Ramírez: Framing His Life and Art (University of Texas Press, 2015), in Hyperallergic. Also see Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s 2007 lecture at the American Folk Art Museum, which contextualized Ramírez in terms of many aspects of Mexican culture. In a 2007 New York Times review titled “Outside In,” Roberta Smith wrote that the Folk Art Museum exhibition “should render null and void the insider-outsider distinction.” She said Ramírez “is simply one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.”

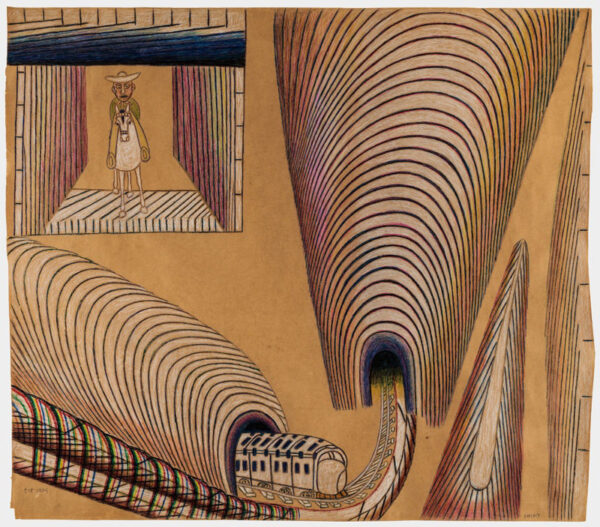

Martín Ramírez (b. 1895, Jalisco, Mexico; d. 1963, Auburn, California), “Untitled (Train and Tunnels),” 1954, pencil, colored pencil, crayon, and watercolor on paper, 36 x 41.25 inches, courtesy Ricco/Maresca Gallery. Photograph: The Brooklyn Rail.

Ramírez’s vertiginous, nearly parallel lines create strange forms that seem to oscillate spatially.

The death figure in The Black Balloon, much like a New Mexican folk painting of a saint, inhabits a space framed by symmetrical tied-back curtains. She wears what could be mistaken for a nun’s habit, but she is meant to the Grim Reaperess. Death is gendered female in Spanish, and La Parca, the reaper figure brought by the Spanish, was understood as female. For a brief discussion of La Parca, Santa Muerte, and the New Mexican Doña Sebastiana (as well as the origins of Catrina), see my “Catrina I” in Glasstire.

Instead of a sickle, the Grim Reaperess holds a black balloon. Maldonado explains that balloons are “usually very loving and playful symbols.” They are bought for children and featured at parties. Maldonado’s purpose in substituting this object of innocence and fun for the sickle (the implement that symbolizes the harvesting of human life) is to create a “humorously terrifying image.” The artist compares this juxtaposition to the soldier in Stanley Kubrick’s film Full Metal Jacket (1987), who simultaneously wore a peace sign and a helmet inscribed with the phrase “Born to Kill.”

The linear patterns found in New Mexican folk art and Ramírez’s drawings blend almost seamlessly in The Black Balloon. But the figure’s skull is made up of solid geometric forms. As in all but two of Maldonado’s pieces in Crossing Borders, the heads are divided into three basic parts: one section for each eye, and one for the mouth and jaw. The nose attaches to one of these three areas (in The Black Balloon, it rests squarely on lower section with the jaw and teeth).

While Maldonado’s heads reference Cubism, they are very unlike Picasso’s heads, which, even in the 1930s, exhibit a tension between two and three dimensions. Maldonado’s heads, by contrast, could easily be translated into sculpture. Maldonado gives this account of the Picassoesque heads:

The Picassoesque head is something I have done for over a decade now. It came out of an idea of putting up graffiti with Cubist characters and signing it “Picasso Thief.” I never was ballsy enough to become a vandal again so I just expressed those ideas on my canvases.

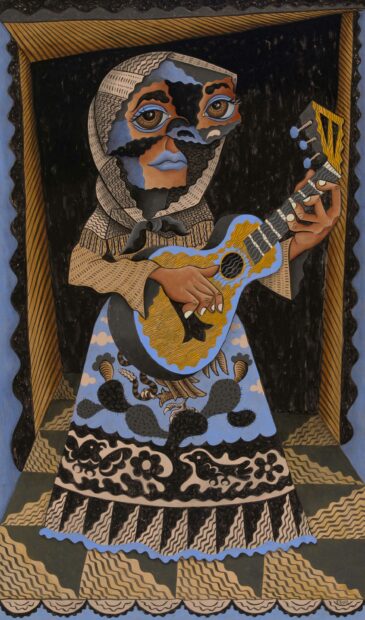

The title Blue Period Guitarista references Picasso’s The Old Guitarist (1903-04), one of the artist’s iconic Blue Period works, now in the Art Institute of Chicago. Maldonado has transformed the guitarist into a woman, one whose head covering refers to the women in mantillas that Picasso painted over the course of many years. But the simple, black and white graphic marks that make up this mantilla do not define space. Instead, they are like the newspaper clippings and the other elements deployed in the early collages made by Braque and Picasso. This entire work, in fact, is broken up into so many small areas of repetitious forms (black-and-white collage-like strips, small areas of blue, black, brown, and off-white) that the illusion of figural solidity is thoroughly compromised. It reads like a collage because it could easily be a collage.

The doorway is off-kilter, distorted by triangular devices with linear hatching like those found in Ramírez’s drawings and Picasso’s collages and paintings. The triangular elements in the lower part of the guitarist’s skirt seems to want to dissolve into the floor, which itself is made up of triangular elements.

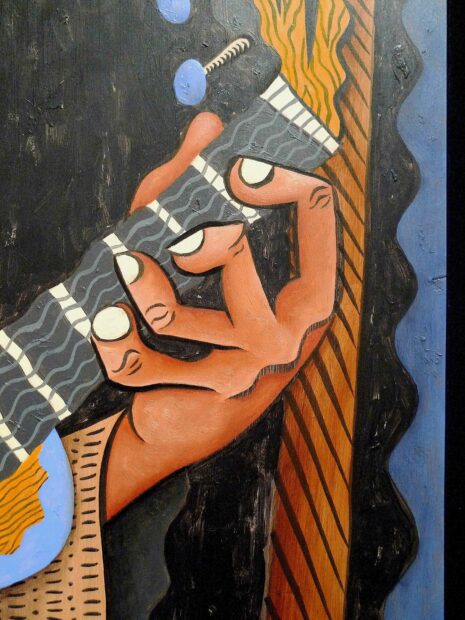

Brandon Maldonado, “Blue Period Guitarista” (detail of left hand), 2021, mixed media on panel, 36 x 21 inches. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The guitarist’s hands (the left one in particular) are similar to the hands Picasso painted in his Guernica and Weeping Woman phase. The areas of wood-grain pattern on the guitar’s body and head stock make yet another reference to Cubism. It resembles the faux bois (imitation wood grain) wallpaper that Braque and Picasso used in their early collages.

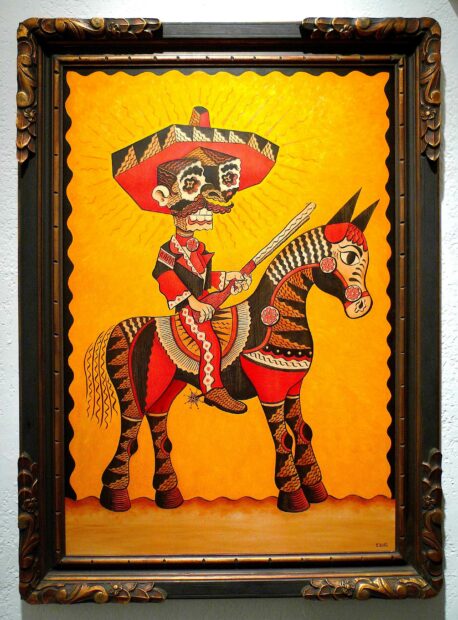

Brandon Maldonado, “Zapata Lives,” 2021, mixed media on panel, 38 x 25 inches. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

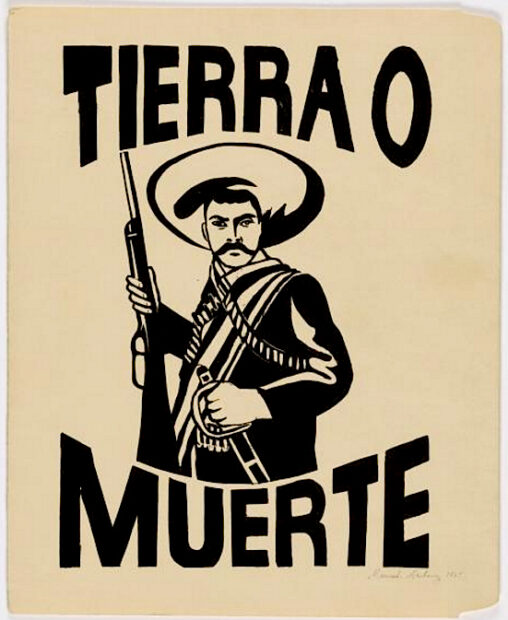

The Mexican general Emiliano Zapata serves as the righteous emblem of the Mexican Revolution. His famous slogan, Tierra o Muerte (Land or Death) resonated very specifically in New Mexico. After the seizure of half of Mexico following the Mexican American War, which ended in 1948, longstanding claims to land (both familial and collective) were violated. In one of the major events of the Chicano movement, Reies López Tijerina dramatically sought to redress these violations. In 1967, he led a raid on the Rio Arriba County courthouse in Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico. See: National Museum of American History and Tierra Firme.

Emanuel Martinez, “Tierra o Muerte,” 1967, screenprint on manila folder, 11 3⁄4 × 9 1⁄2 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Photograph: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Emanual Martinez utilized Zapata’s image and slogan in a screenprint made in 1967. For a mural by Antonio Bernal with Tijerina as a successor to Zapata, see my “Reyes 2” article in Glasstire.

Zapata, along with other major Mexican historical figures, features prominently in Maldonado’s work. In Zapata Lives, the general is astride what appears to be a Mexican folk art horse.

Brandon Maldonado, “Zapata Lives” (detail of head and hat) 2021, mixed media on panel, 38 x 25 inches. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Maldonado’s Cubist rendering of the head and hat might at first seem out of phase with the folkloric horse. But the longer one looks at the horse, the more one sees kindred geometric elements.

We might also recall that the scholars who have historicized and contextualized Ramírez’s work noted his connection to religious and folkloric Mexican art.

In terms of technique, Maldonado deliberately courts an antique look (which is evident in the detail reproduced above):

I like how the old classical retablos are all scratched up, so that is part of my approach. I scratch up the initial ink layer to hit towards that distressed look. Then I come back and darken areas with oil paint to create an implied value gradient. So other than the technical experiments I am putting in squiggle strokes and other motifs that the santeros liked to use.

Maldonado accentuates secondary elements such as drapery and floor tiles, with the aim of creating “repetitive line work that radiates and hopefully captivates like a psychedelic image that seems to breathe.” He concludes: “So I’m trying to live in this world of psychedelic-folk-neoCubismo-Mexicanismo.”

Maldonado explains that Brothers “tells the story of how we are all brothers to mother death who will be our last nurse, sea de principe o serviente, blanco o negro” (whether prince or servant, black or white).

Vicente Telles

Mexican, “Mano Poderosa (The All-Powerful Hand), or Las Cinco Personas (The Five Persons),” 19th century, oil on metal (possibly tin-plated iron), 13 7/8 x 10 1/16 inches (35.2 x 25.6cm), The Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Though Telles often makes works based on New Mexican santero art (either traditional or non-traditional), the sole painting in this exhibition with a close connection to religious art is based on a Mexican theme. The Mano Poderosa is one of the most fascinating subjects in Mexican popular art. It typically features a hand with a bleeding wound that symbolizes one of Christ’s crucified hands (usually the right one). A small image of Christ is perched on the middle finger (or the thumb), and his parents and maternal grandparents are on or above the other fingers. Some examples feature other elements, such as God the Father in heaven, angels, and a chalice or basin that captures the hand’s blood, and sheep (almost always seven), which drink the sacrificial blood out of the container (as in the version in Brooklyn, illustrated above).

Vicente Telles, “La Mano Poderosa,” 2021, foraged and commercial watercolor pigments on gessoed panel, 17½ x 13¾ inches.

Telles’s La Mano Poderosa features a left hand, above which float a sweatshop sewing machine, a bucket of harvested fruit, a leaf-blower, and a cart with cleaning supplies and fresh towels (the kind used by hotel cleaning staff). Telles comments: “The all powerful hand is what keeps this country rolling.” His hand is that of the migrant Latino, whose job opportunities are often limited to professions that are disdained in the United States. Seamstresses, field workers, landscapers, and cleaning people are all needed for the economy. In fact, as the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated, they are essential workers. As Telles notes, this is all “work that needs to be done,” but the laborers who perform these tasks are dehumanized.

Above the middle finger (the space inhabited by the Christ child in the Mexican painting illustrated above), Telles has painted a graduation cap and gown and a Mexican textile. But he has left this graduate anonymous, bodiless, and faceless as well. The workers are altogether absent. Telles wants the viewer to imagine whose parents or grandparents performed these arduous, low-paying and unappreciated jobs in order to provide their descendants with an education and a better life.

Vicente Telles, “La Mano Poderosa” (detail of lower center), 2021, foraged and commercial watercolor pigments on gessoed panel, 17½ x 13¾ inches.

Instead of rising from a basin of blood, Telles’ powerful hand rises from the U.S.-Mexico border wall, which it wears like a shirtsleeve. In the detail above, one can see that the gray, ruff-like barbed wire that tops the fence has inflicted multiple wounds on the wrist. The nopal cactus plants that frame the hand have wounded both the hand and wrist. These wounds allude to the “struggle and sacrifice” that immigrants undertake “in order to attain a better life for future generations.”

Vicente Telles, “Mi Amigo the Pigeon,” 2022, watercolor and oil pastel on gessoed panel, 22 x 18 inches.

When Telles created this piece, he reflected on “all the negative things people have said to me while making or pursuing my art.” At times, he felt as if he were being “bashed” like a donkey piñata for following his artistic vocation.

The pigeon (with its own diminutive piñata head) that sits on Telles’ shoulder is a reminiscence of his childhood, as well as a symbol of how many U.S. citizens view people of color. They are, says Telles, “seen but not respected, industrious yet dehumanized. [They are] taken for granted.” He adds that despite all this negativity, “we continue to prosper and pursue our dreams because we are good vecinos (neighbors).”

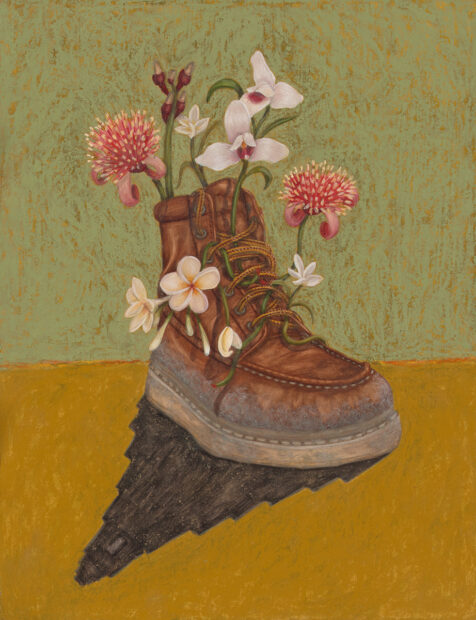

Vicente Telles, “Flor y Sombra” (Flower and Shade), 2021, watercolor and oil pastel on gessoed panel, 13¾ x 10¾ inches.

Flor y Sombra is a reconceptualization of manual labor performed by Mexicans and Latinos in the construction industry in the United States. A work boot, which is coated with cement residue, sprouts flowers and casts a pyramidal shadow.

Rather than regarding these workers as unskilled laborers, Telles notes that they are descended from great builders: “it is in their DNA.” The pyramidal shadow specifically references Tikal, and by implication, all Mesoamerican pyramids. The flowers, in turn, “represent the beauty that these workers are creating and that we benefit from without giving it two thoughts.”

Their ancestors were engineers, skilled stonemasons, and builders of great works. Flor y Sombra is a way of “giving these workers nobility in the craft in which they work day in day out.” Telles recognizes that they make “countless decisions and improvements” and work with real artistry in their given crafts.

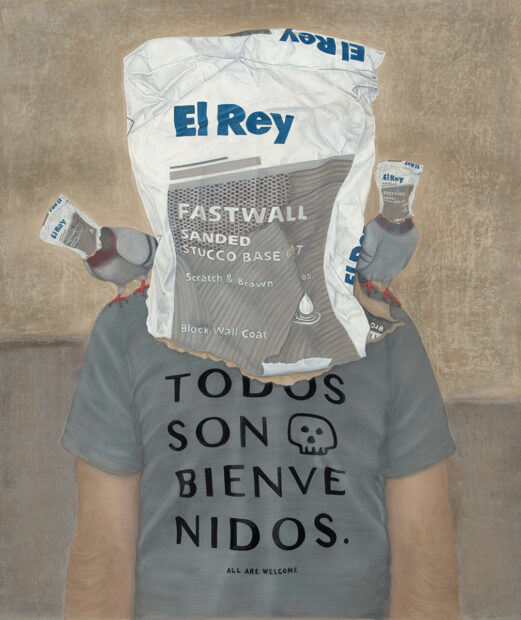

Vicente Telles, “Los Tres Reyes” (the Three Kings), 2022, watercolor and soft pastel on gessoed panel, 29 ¾ x 25 inches.

Telles calls Los Tres Reyes “a nod to those workers building America.” The three figures (the man and the two pigeons) all have a bag of El Rey fastwall stucco base over their heads. In this oblique manner, it references Los Reyes Magos (the three kings).

As in his other depictions of pigeons in this exhibition (including Mi Amigo the Pigeon, discussed above), these birds represent anonymity as well as ubiquity. Like Latino workers everywhere, their presence is generally “unnoticed and overlooked.”

Telles argues that despite the hardships Latinos face in many parts of the U.S., “an honest paycheck and industriousness will have us in every city… as widespread as pigeons.” The gray shirt blends in with the pigeons and the gray wall. The words inscribed on it (Todos son Bienvenidos / All are Welcome) convey a welcoming message. This should be true, says Telles, “regardless of occupation.” He adds: “There is nobility in working with our hands and creating the housing and infrastructure that we rely on everyday to live a comfortable existence.” Telles means to affirm the craftspeople that build this nation. At the same time, the skull on the shirt recognizes the hazards of immigration and the difficult circumstances faced by immigrants.

Ricardo Islas

Born in 1970 in Calexico, California, which is 120 miles east of San Diego on the Mexican border, Ricardo Islas moved to San Diego in 1991, where he continues to live and work. Equally interested in folk art, Surrealism, and mass culture, Islas draws on fine art and popular culture from many sources. He notes in his artist statement:

I take my inspiration from anywhere I can find it, a dirty joke, a funny saying, or a story told at a bar. I hope to show the viewer another side of Mexican/Chicano culture that may be unfamiliar to them. I am painting experiences, some personal and some broader. I am trying to expose the harsh reality of life. I sometimes use funny imagery, but there’s always a more profound message hidden for the viewer to discover in my work.

The central element of the house in the work above takes the form of a Tlaloc vase. Tlaloc was the Aztec rain god. It is blue because that is the sacred color of water. Tlaloc’s round eyes are formed by stylized snakes. Islas has transformed them into round windows. He also has endowed the sculptural façade with what appears to be a tongue window on the lower level (framed by earth-colored fangs).

The ancient indigenous architecture expresses priority: Chicanos were here first. The ancestors of today’s Chicanos inhabited the present-day Southwest before there was a United States. In fact, Chicano mythology — created during the Chicano movement — holds that the U.S. Southwest is Aztlán, the mythical homeland where the Aztecs lived before they migrated to the Valley of Mexico. The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán manifesto was adopted at the First National Chicano Liberation Youth Conference held in Denver, Colorado in 1969.

The highway in the background serves as a reminder of how highways cut through ethnic neighborhoods, and the refinery indicates how hazardous and polluting industries were situated near barrios rather than affluent areas. The television antenna is an indication of low income — the inability to afford cable. Barrios have also been the last areas to get access to cable and internet. This neighborhood is probably also a food desert (at least in some respects).

The “Not for Sale!” sign emphatically opposes relinquishing this homeland. Islas calls the sign “a middle finger to gentrification.”

Even with longstanding disadvantages, the owner of this house does not want to be displaced. Soaring real estate prices mean soaring rents (for renters) and soaring property taxes (for homeowners). This makes it difficult to keep one’s apartment or house in the face of gentrification. Islas notes that gentrification “is happening in many barrios.” Islas has treated gentrification in a number of works.

Islas notes that in Barrio Logan, a Mexican / Chicano community in San Diego, “many people are having to leave because they can no longer afford to pay sky-rocketing rents.” Barrio Logan is an industrial area that was bisected by a highway. Chicanos claimed the area under the highway, which they adorned with murals and named Chicano Park. For the history of Chicano Park, as well as images and a virtual tour, see Chicano Park San Diego.

Islas discussed Barrio Logan:

Barrio Logan is next to the water but it is used by the shipping industry and military. The air quality is the worst in the city and has a higher percentage of kids with asthma. The bridge on the right is the Coronado Bridge, which on one side is one of the poorest neighborhoods. On the other side is one of the highest income areas in San Diego.

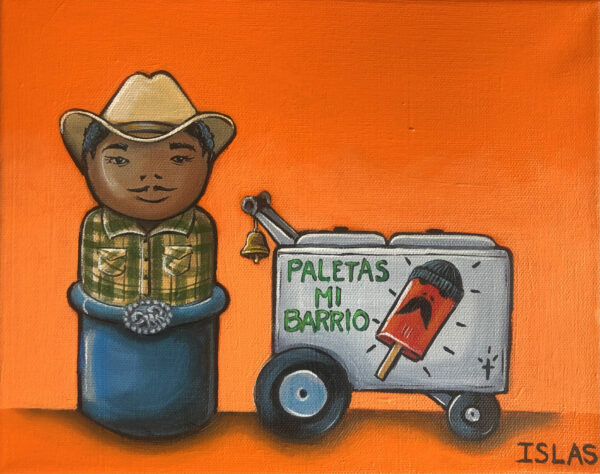

Paleteras, shaved ice and popsicle vendors, have been depicted by a number of Chicano painters, including Jesse Treviño’s La Raspa (1976) and Frank Romero’s Arrest of the Paleteras (1996). Paleteras are barrio fixtures, and they have always been harassed by the authorities.

Islas notes:

Vendors have been all over the news being robbed and physically assaulted for trying to make a living. With gentrification, people move into a new neighborhood where the paletero has made a living for years, then turn around and complain about the street vendors in their new neighborhood.

Paletas mi Barrio, the name of the business, stakes a claim on the barrio, which is reinforced by the anthropomorphized paleta. The stocking cap emphasizes that the paletas are cold. The radiating cross in the lower corner is a popular tattoo, one that is thought to confer good luck and protection. Implicitly, the radiating paleta should do the same.

Islas clarifies the choices he made in decorating the cart:

The face I drew on the paleta reminds me of other business in the Barrio, for example, Tacos El Cholo. When I see names like that, it says I’m here for the neighborhood customers. We’re not trying to go mainstream. They know who their clientele is. Also when I see the paleta, I imagine the paleta warning other Paleteros that this is his turf to sell paletas.

Islas based the body shape of the paletero on a classic American toy by Fisher Price called Little People. They are for toddlers, and have a round head and a cylindrical body. Islas began painting Chicano versions of the Little People toys in 2005, for a solo show called ToyzRn’tUs. He explains: “I felt most toys represented white people so I started converting classic American toys into Chicano Versions.” In addition to Little People, he has “converted” Weeble Wobbles (which he calls Ahuevo Wobbles), green army men, the Operation game, Red Wagon, and a few others.

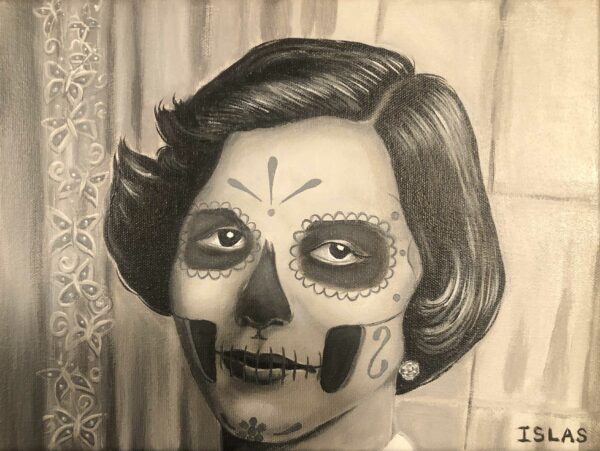

Islas has always had an appreciation for old pictures, including black-and-white and sepia toned photographs. La Classy Muerte depicts a woman Islas imagined as someone at a fancy cocktail party, wearing makeup appropriate for a Dia de Los Muertos theme.

This muerte from another era is not herself deceased, so she is a phantom, like one in an old black-and-white photograph. Islas concludes: “It reminds me that we are all human and at some point will meet our fate.”

This painting is based on the cruising experience. “The Ride or Die” is slang for a best friend or girlfriend “that always has your back.” Islas explains that if a fight broke out, “The Ride or Die” homie would jump in, “regardless of the danger or consequences.”

Your girl would also “always has your back, just like the Adelitas during the Mexican Revolution.”

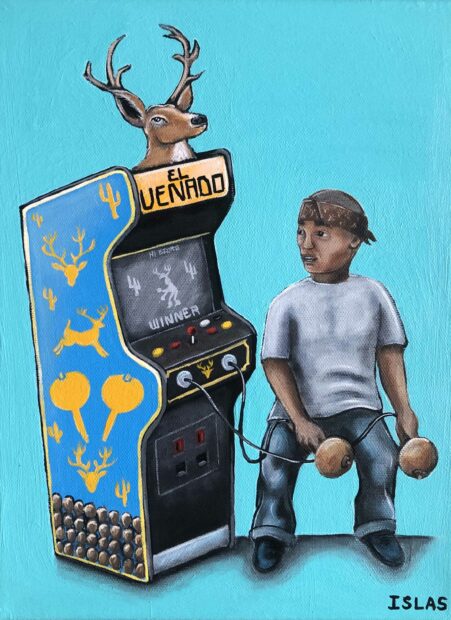

La Danza del Venado (the deer dance) is a native Mayo and Yaqui dance from northern Mexico. The dancer, who dances with rattles and shells, wears a deer headdress and impersonates a hunted deer, which dies at the end of the performance. La Danza del Venado honors deer and the willing sacrifice the animals make to provide sustenance to humans. Deer are regarded as sacred animals to these indigenous cultures.

In Islas’ painting, an urban vato grasps the rattles and does his best to learn the dance, wearing only a scarf on his head. We can contrast Islas’ El Venado game to the Big Buck Hunter arcade game. In the latter, billed as “the world’s favorite hunting game,” two players each aim a rifle at the screen and compete to kill as many big bucks as possible in the allotted time frame. The Big Buck Hunter® Reloaded version (pictured below) has new features, including “Zombie Deer.”

Islas says his painting is “about losing our culture because stories are not being passed down” directly from parents and grandparents to children. It poses the question of how “our own history” is transmitted, whether via first hand accounts or through technology.

The device of the video game symbolizes the loss of the direct transmission of culture. Islas elaborates: “Most kids are on the phone or iPad and I imagine kids learning about their culture through a video game, just as people get their news through slanted media outlets and not true news sources because it’s convenient.”

The video screen announces that the vato is a “winner.” He has therefore mastered the dance, and learned how to symbolically sacrifice himself for the benefit of the community.

***

Crossing Borders: Tres de Oeste was on view from April 1 – April 30, 2022 at Presa House Gallery.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.