Borderwavve, the current exhibition at San Antonio’s Presa House Gallery, features abstract paintings and assemblage works by four Texas-based artists who have strong ties to the Texas/Mexico border. Three of the artists, Gerardo Arellano, Jorge Puron, and Aldo Fabian Ramos, were born in Mexico, while the fourth, Cande Aguilar, hails from nearby Brownsville. According to the show’s premise, works by these artists reveal “a new aesthetic of abstraction and border culture that draws upon the artists’ bi-cultural identity. The phrase (‘Borderwavve’) connotes a constant state of deconstructing and rebuilding connections between traditional and modern Mexican and American customs.”

The current SATX/MX exhibition at the Centro de Artes also showcases works by artists living in the cultural gray zone between Texas and Mexico, but is devoid of abstract painting. Borderwavve, in contrast, calls attention to apolitical means through which artists influenced by their bicultural identities express themselves. For the most part, rather than work with easily identifiable and often loaded imagery, the Borderwavve artists express their ideas and feelings more in code, something that is inherent to the language of abstraction as it has been employed to a large extent since the early 20th century, along the lines of Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian. Abstract artists have a greater challenge if they intend to communicate anything beyond emotional content to viewers. The artists in Borderwavve haven’t introduced a whole new aesthetic (with the possible exception of Aguilar, who uses found materials that could be associated with Mexican culture), or told us much about their identities. But they have offered up some beautiful works of art that demand our attention because they are skillfully crafted, formally resolved, and visually engaging.

Gerardo Arellano, Ciudad de Lluvia (City of Rain), 2011, mixed media on canvas, 23 3/4 x 35 3/4 in., photo: Jenelle Esparza

While all of these artists use Abstract Expressionist foundations, the one who appears the most tied to the movement’s tradition is Austin-based Gerardo Arellano, represented here with a number of landscapes. Constructed using a vocabulary of fluid organic shapes (some of which bring to mind Terry Winters’ abstractions of the ’80s), Arellano’s most inspired paintings are those that respond to the environmental and cultural characteristics of a place that have little to do with his Mexican origins. Painted while Arellano lived in Seattle in 2011, Ciudad de Lluvia (City of Rain) and Seattle bustle with energy in the form of raindrop patterns interspersed with rhythmic swirls and undulations that can be felt beyond the paintings’ borders. In the former, Arellano uses a soft palette and thin washes to (effectively) romanticize the temperament of a rainy day—a subject that is not so culture-specific. In the latter, he abandons gestural brushwork in favor of flatter shapes that refer to the mountains and pine trees of the Pacific Northwest, while also paying homage to Seattle’s thriving music and comic-book scenes through the use of bold, clashing colors. According to the artist, the cartoonish figures with stars for eyeballs are influenced by the Beatles’ animated movie, Yellow Submarine.

Jorge Puron, Casa Matriz #6: El Sediento (Matrix House #6: The Thirsty One), 2016, enamel on canvas, 48 x 54 in.

Jorge Puron has been exhibiting in San Antonio since the late ’90s, and for many years he was a predictable practitioner of conventional, thickly painted gestural abstractions. This all changed in 2014 when, to his credit, he recognized the limitations of his Abstract Expressionist approach and veered in the opposite direction, by adopting a gesture-free geometric vocabulary that has enabled him to focus more on structure than on emotional content. Specifically, Puron has been painting elegant geometric abstractions based on cultural objects familiar to both Mexican and American practices, as well as on personal memories of his early life in Piedras Negras, Mexico. The image source for Vector #3 (2015) is a television set on a table, but we don’t need to know this in order to appreciate the beauty of the painting. As a hybrid of compositions pioneered by historical figures such as Josef Albers and Victor Vasarely, it is optically alive with a dazzling interplay of shapes and colors. In other works, such as the more complex Casa Matriz #6: El Sediento (2016), which was inspired by memories of a grocery store where the artist worked as a child, Puron demonstrates his adeptness at creating contradictory spatial relationships that keep our eyes moving throughout the painting as if we are traveling virtually through the corridors of a maze. This particular painting carries a sense of intrigue; some of the images within hint that there’s more to what we are looking at than pure geometry. In the same way we decode a Cubist work by Picasso, we can decipher the face of a thirsty delivery man at upper left, and recognize a glass of water on a table at lower right.

Aldo Fabian Ramos, Almas (Souls), 2014, mixed media on wood (triptych), 5 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. each panel, photo: Jenelle Esparza

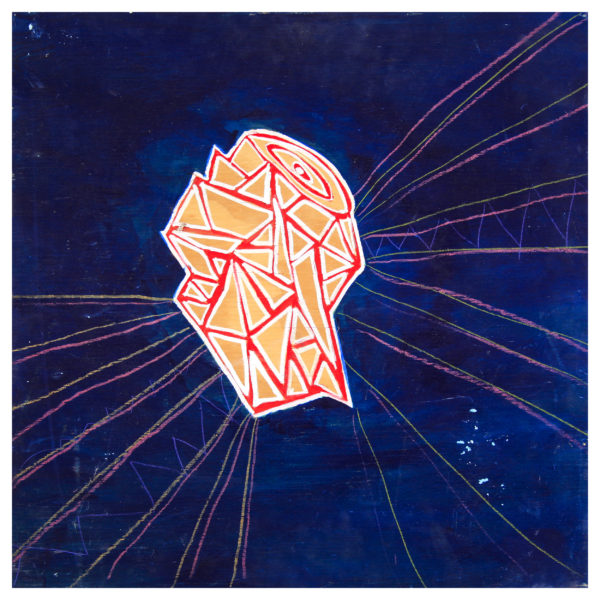

Although San Antonio’s Aldo Fabian Ramos and Brownsville’s Cande Aguilar have each contributed more typical gestural abstractions to Borderwavve, their more interesting works are also those that lie outside the realm of Abstract Expressionist conventions. In fact, both artists achieve their finest moments when exploring personal symbols and metaphors. Constructed mostly from triangles, the central emblematic image in Ramos’s Geo (2012) resembles a precious stone, which for the artist represents a sacred heart—an expression of eternal love that he has connected to a celestial blue universe using a system of expansive lines. From a purely aesthetic standpoint, the image seems filled with energy that could propel it forward into the viewer’s space. In Ramos’ small triptych Almas (Souls) (2014), the animated movements of geometric patterns and linear matrices allude to interconnectivity and the invisible matter that makes up the human spirit.

Cande Aguilar, Confetti in a Bag, 2016, confetti in a plastic bag, 9 x 5 x 1 in., photo: Jenelle Esparza

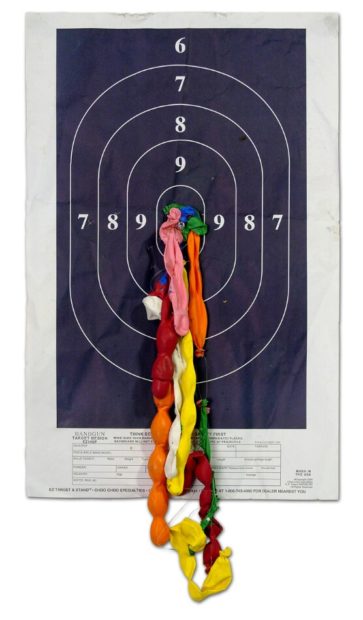

Cande Aguilar, Untitled, 2016, deflated balloons on target paper, 27 x 14 in., photo: Jenelle Esparza

Of the four artists in the exhibition, it’s Cande Aguilar—the only one born in the United States—who’s showing art that immediately brings to mind associations with Mexican culture. This isn’t discerned through his abstract paintings, but rather in his found-object assemblages from a series that he calls ‘barrioPOP.’ In Confetti in a Bag (2016) and a recent untitled work, Aguilar uses confetti and balloons, materials commonly associated with fiestas, to express his feelings of fear and disgust over Trump’s rhetorical assault on Mexican Americans. Bagging the confetti refers to oppression, by containing the happiness and freedoms that are inherent to acts of celebration. Attaching deflated balloons to a paper gun target conveys the emotional exasperation felt by Aguilar over Trump’s alliances with the NRA and its gun-toting followers.

The exhibition continues at Presa House Gallery through December 23.