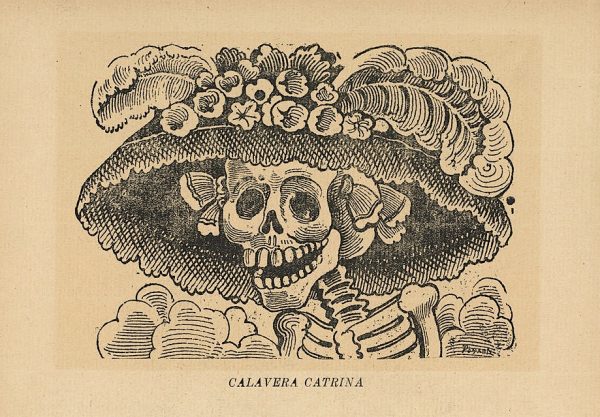

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), image (now referred to as Catrina) created for Day of the Dead broadside, image design c. 1910, first printed (in the broadside illustrated below) in 1913. Independent Catrina images, like the one illustrated here, date from much later. See the image printed in a 1943 portfolio in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One day the Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada created an image of a skeletal woman with an ostrich-plumed hat large enough to be an umbrella. He could not have had the slightest inkling that — with help from muralist Diego Rivera in 1947 — an elaborated version of his creation, which became known as Catrina, would become the single most influential and ubiquitous visual symbol of modern Mexico. Posada’s humble print, which is just a head and skeletal shoulder image (henceforth referred to as “Catrina” in quotes), engendered millions of descendants, both in Mexico and around the world. These include all manner of prints, paintings, murals, commercially printed cardboard cut-outs, book illustrations, posters, tattoos, t-shirts, mugs, engraved shot glasses, ceramic and papier-mâché sculptures, papel picado (crepe paper cut-outs), votive candle holders, parade floats, Mexican lottery tickets, and costumed human impersonators. The Google Day of the Dead “Doodle” for 2019 features a Catrina image, as did the 2013 Doodle. But don’t believe the Doodle text: Google clearly googled the wrong sources. See my Glasstire article Is Day of the Dead More Indigenous or Spanish? Friars Durán and Sahagún vs. Wikipedia.

Catrinas — in all their manifestations — are generally regarded as personifications of Mexican-ness itself, often in pointed contrast to images derived from Halloween traditions imported from the United States. Many Mexican commentators and cultural nationalists have characterized Halloween costumes, decorations, and paraphernalia as contaminating cultural invaders that, at the very least, potentially weaken, imperil, or falsify Mexican culture as embodied in Day of the Dead (Día de los muertos), which in 2008 was recognized by UNESCO as constituting part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The Jack-o’-lantern and Catrina are warring symbols: just as the former stands for Halloween, the latter is posited as an authentic symbol of Mexico as embodied in the Day of the Dead.

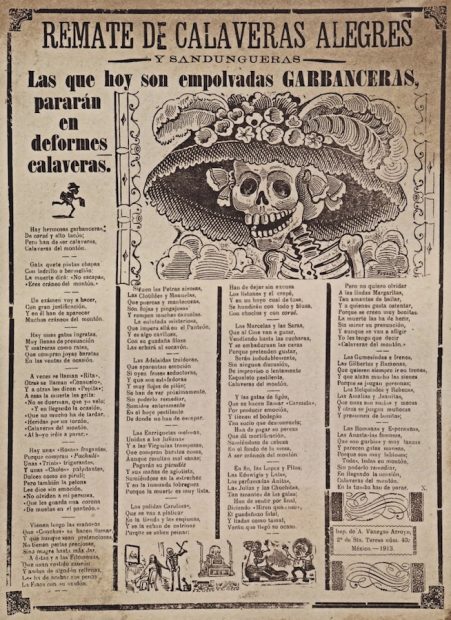

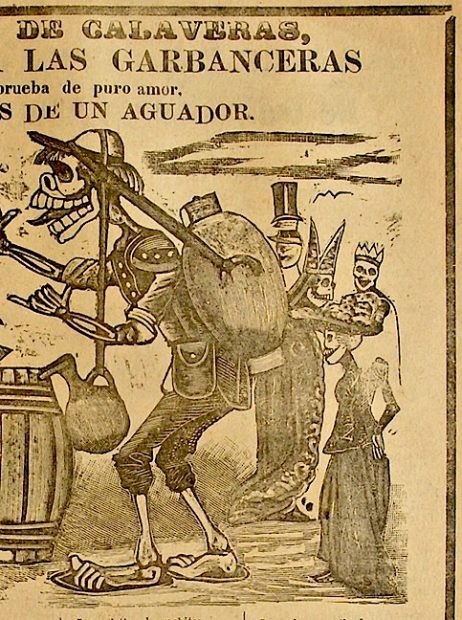

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), Remate de Calaveras Alegres y Sandungueras, image design c. 1910, photo-relief etching, dated 1913 in lower right

This phenomenon is more than a little ironic, since the image initially satirized the betrayal of Mexican culture. Rather than exalt this imaginary figure as a symbol of national pride and character, Posada mocked her for aping European fashions. Diego Rivera transformed Posada’s big-hatted woman into what has become a fully articulated and enduring symbol of Mexican culture. He essentially inverted her significance. Whereas Posada’s creation was analogous to the Jack-o’-lantern, Rivera’s version functions as its antidote, like a powerful talisman warding off a menacing devil (the Jack-o’-lantern) and its minions.

Posada is thought to have created his design for the print around 1910, or slightly later. Its first known publication date is 1913, for the Day of the Dead (Posada had died that January). The broadside is titled Remate de Calaveras Alegres y Sandungueras, Las que hoy son empolvadas Garbanceras pararán en deformes calaveras (The Ending of the Cheerful and Sandunga-dancing Calaveras [calaveras could refer to skulls or skeletons, to rhyming mock obituaries, and to the Day of the Dead broadsides themselves], those that today are powdered chick pea-vendors will end as deformed Calaveras). Posada had no part in writing the verses that accompanied his images, though the caustic, witty, and innovative language they employed is said to complement his images. Moreover, the Vanegas Arroyo family that printed the broadsides recycled the images, using different titles, texts, and subsidiary images. My take on Posada and his printer (see the catalogue to my San Antonio exhibition The Day of the Dead in Art; for Glasstire‘s review of the exhibition, please go here) draws on the scholarship of Thomas Gretton.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Day of the Dead—City Fiesta, detail of dark-skinned Mexican women with powdered faces, 1923, fresco, Court of Labor, ground floor, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

Garbanceras sold chick peas. Unlike indigenous foods like corn or beans, garbanzos were introduced to Mexico by the Spanish. So these vendors — by the very nature of their wares — eschewed indigenous cuisine, and, by implication, Mexican culture. The title refers to them as “empolvadas” (powdered), an inference that they were lightening their skin with powder to obscure their mestizo or indigenous origins. Even light-skinned European women wore pale make-up to appear as white as possible. To wear a flamboyant European hat had racial and cultural significance: it signaled admiration and identification with European culture. Mexico was ruled by a Francophile elite that denigrated indigenous and mestizo cultures and traditions. Fashionably large hats protected women’s hair from getting dirty. They also protected facial skin from burning or tanning. Racism caused white skin to be valorized. Whiteness also had a class component: it served as a sign that the woman was a “lady” who did not have work in the sun.

The text in the Garbancera broadside describes garbanceras in extraordinarily vicious and misogynistic terms: as cat-like, rat-like, vain, pretentious (but poor), flirtatious, seductive, and false. They are ridiculed as lower-class women who buy clothes on sale and make pretensions of belonging to a higher station. They are condemned as untrustworthy, since not even their appearance is something that can be believed. Clothing functioned as markers of class and race. In this context, absurdly impractical and expensive accessories, such as giant hats built on metal frames, with quantities of fine lace, silk flowers, and exotic bird feathers (and sometimes bird wings or entire stuffed birds!) served as ostentatious markers of class. As noted in the book Mrs. Parkhurst’s Purple Feather by Tessa Boase, a single ostrich feather was worth 140% of a working person’s weekly wage in the U.K. At least that’s cheaper than osprey feathers, which, measured by weight, were twice as valuable as gold. Vanegas Arroyo aimed his broadsides at a downscale mestizo male audience. He had to please them in order to part them from their pennies. They were predisposed to view a garbancera with a massive European hat as a preposterous imposter, and secondarily as a race and class traitor as well. The prospect of such a hat on a skeleton is even more ridiculous, as are the hair ribbons without hair. The women who wore these hats needed big hair and abundant padding just to keep them on their heads. Hats could be wider than a woman’s shoulders or hips, and were vulnerable to wind. Additionally, all skulls are permanently white, and they have no skin that needs protection from the sun.

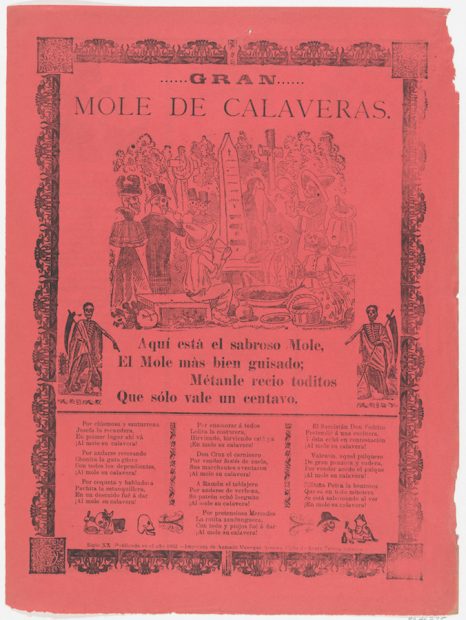

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), Gran Mole de Calaveras, photo-relief etching, 1902, collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A premonition (or inkling) of the “Catrina” figure made an appearance on the far left of a broadside called Gran Mole de Calaveras (Big Mole [sauce] of Calaveras). A formally dressed female skeleton wears a hat with two ostrich feathers. Proportionately, it is much smaller than the one in the “Catrina” image because it is an evening hat and therefore not designed to provide shade from the sun. In the last few years of his career, Posada rendered images with cartoonishly large heads and hats.

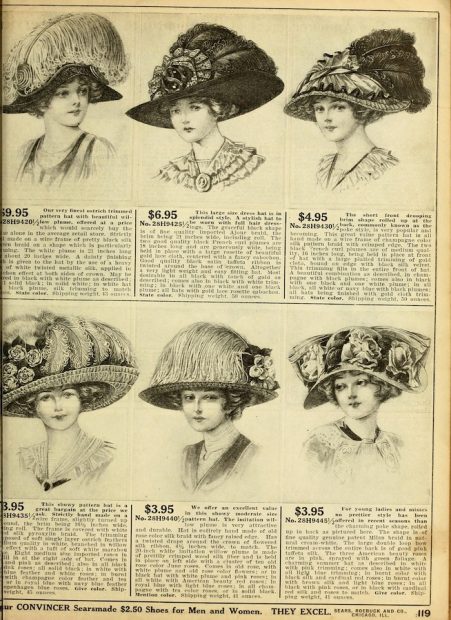

For more examples of enormous hats (including the one pictured above) as well as smaller evening hats, see: The Trecce Fatale Project. The hat illustrated above was likely influenced by the hat in Posada’s print, and similar lightweight hats are worn by today’s Catrina impersonators.

In any case, big hats with ostrich feathers were still the rage in 1912, as attested by Sears, Roebuck and Company. The item in the lower left of the above illustration is 16 ½ inches wide and has a shipping weight of 45 ounces.

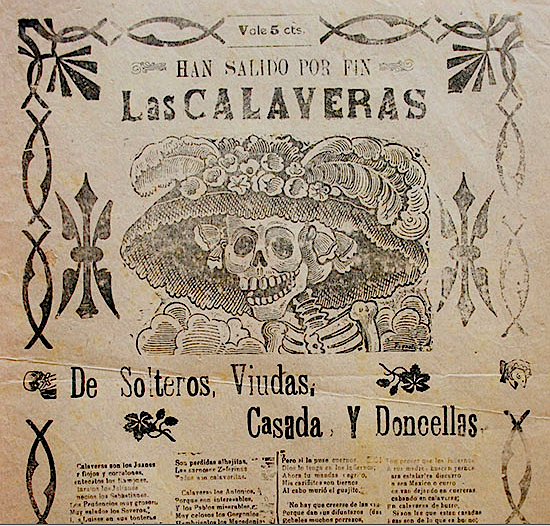

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), Han Salido por fin, detail, photo-relief etching, probably published 1917 or after, collection Museo Blaisten.

Posada’s “Catrina” image was used in a rare broadside, titled Han Salido por Fin, Las Calaveras.

The title translates as “They have finally left,” but it could also punningly mean “They have gone out for the last time.” This broadside is priced five cents and was issued after the death of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo in 1917, though we do not know how soon after his death.

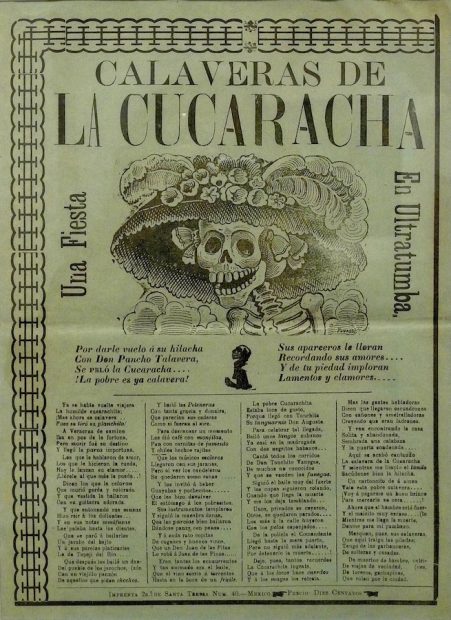

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), Calaveras de la Cucaracha, Una Fiesta en Ultratumba (Calaveras of the cockroach, a fiesta from beyond the grave), photo-relief etching, broadside probably printed in the 1920s, collection of Lance Aaron and Family, The Day of the Dead in Art exhibition, Centro de Artes, San Antonio, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Another Posada broadside in the Library of Congress uses the word cucaracha. Literally, it means “cockroach,” though it is a slang term used for a soldadera, a woman who accompanied soldiers in the Mexican Revolution (the Library translates cucaracha as “camp follower”). Josephine Van Houten discusses the implications of the song “La Cucaracha” in the context of the Mexican Revolution.

Given “Catrina’s” state of dress (and undress), this image is a bizarre choice to accompany a broadside with cucaracha in its title. Moreover, the text in the first column specifies that the woman in question died fat and “colorado” (which means colored or red, so she could have been dark, or she could have been light-skinned and sunburned), with her beloved guitar. But, most importantly for our purposes, the first line of the last paragraph features the word “catrines, ” which is the plural of the word for a male dandy (“catrín” is the singular form). Catrines is utilized to rhyme with the word “gachupines” (Spanish natives who emigrated to Mexico) two lines below. The male form of the word was likely chosen to make the rhyme. In any case, this is apparently the first time that any form of the word catrín / catrina was published in connection with Posada’s image of “Catrina.”

In the fourth verse of the third column of text, the price is quoted as five cents. But at the bottom, between the two fingers, the price is listed as ten cents. Therefore this broadside was likely republished, with a higher price subsequently inserted at the bottom.

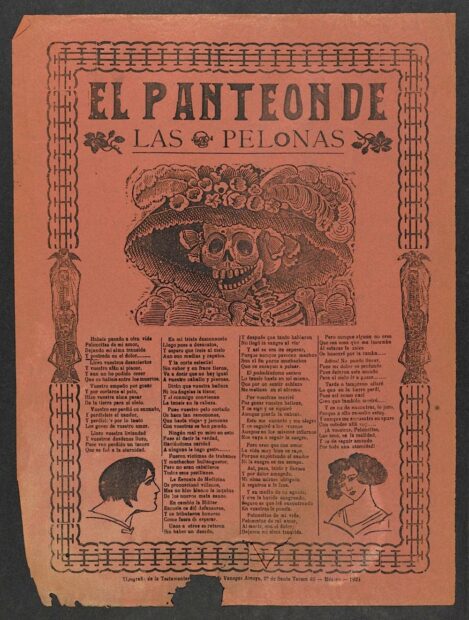

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), El Panteon de las Pelonas, dated 1924 in lower left, photo-relief etching, collection of Stanford University Libraries.

El Panteon de las Pelonas, another surviving broadside with the Catrina image, is dated 1924. As in the Calaveras de la Cucaracha broadside, this one also has a wide border whose central element recalls railroad tracks. Panteón means graveyard. Pelona means bald female, and the word pelona is used figuratively to mean death. The text punningly refers to the death of the narrator’s beloved “peloncitas” (diminutive plural, meaning girlfriends), who have passed on to the other life, from earth to heaven. Note the insertion of two contemporary images in the lower corners, who could be these beloved and departed peloncitas.

Image of “Boyish Bob” haircut from The American Hairdresser, the official organ of the National Hairdressers Association, 1924.

The woman depicted in the lower left of El Panteon de las Pelonas has a bob haircut similar to those immortalized by actress Louise Brooks and the androgynous Flappers of the 1920s, who challenged social norms. Posada’s “Catrina” image was created on or near the eve of the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910. Though it was first published 11 years earlier than this broadside, in comparison with the novel fashions in the lower corners, “Catrina” seems like a relic of a bygone age.

Posada’s “Catrina” image appeared on at least four different surviving broadsides published by the Vanegas Arroyo family. Diego Rivera is usually credited with supplying the name Catrina (the female counterpart to the Catrín) to Posada’s image when it was published in a 1930 book. Rivera, of course, was a notorious liar, who falsely took credit for many things. Moreover, as we have seen, the word catrines was published in the Cucaracha broadside discussed above. Finally, the title choice would have been made by the Vanegas Arroyo family. They still sell “Catrina” prints as independent images (as in the first illustration in this article). This leads to the obvious question: what were Posada’s intentions when he made the image? I don’t think Posada had a program when he made broadside images for Antonio Vanegas Arroyo. They were usually without fixed identifications, and his publisher did whatever he wanted with them, providing them with different texts on multiple occasions. I remember making this point in a class at Sarah Lawrence College, which caused one of my students to spontaneously exclaim: “So he was just a puppet!” Her reaction was based a false image of Posada as a proto-revolutionary artist that was promulgated by Rivera and other artists who admired Posada. On a popular level, this image still prevails. In Posada’s time, the press was strictly censored in Mexico. Antonio Vanegas Arroyo — who did not want to go to jail — often curried favor with the dictator Porfirio Díaz, sometimes with flattering portraits of the dictator made by Posada himself. Vanegas Arroyo’s broadsides sometimes had counter-revolutionary texts. The irony is that the “Catrina” image could be one of the relatively rare instances in which Posada was satirizing the bourgeoisie. But the first text that was attached to it made the image part of a vicious attack on working-class female vendors, reviled more because they are impoverished poseurs rather than for the nature of their social aspirations.

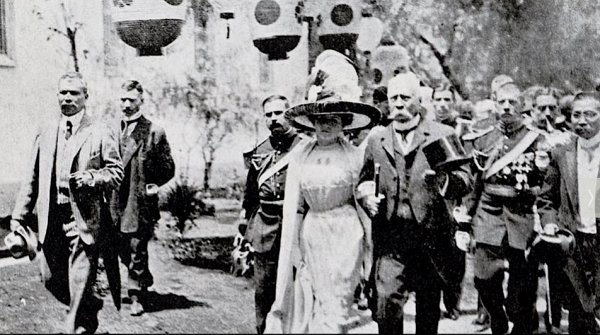

Photograph of Porfirio Díaz and his wife, Carmen Romero Rubio, with the Japanese ambassador Kuma Horigoutchi, as they arrive at the Japanese Industrial Exhibition at the Crystal Palace, September 2, 1910.

Note the heft of the first lady’s feathered hat. If, as is often assumed, Posada created the “Catrina” image c. 1910, perhaps Vanegas Arroyo didn’t publish it in a broadside that could be taken — even inadvertently — as a critique or mockery of ruling-class women until after the Revolution removed Díaz. In early 1913, the elected president and vice-president of the republic had been assassinated, and a usurping counter-revolutionary general who was allied with the old order took power. So, even in 1913, when the Garbancera broadside was published, Antonio Vanegas Arroyo may have wanted to be cautious about the text that accompanied the image.

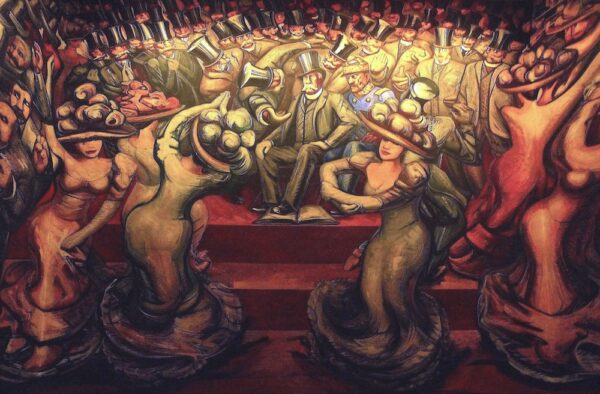

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), From the Porfiriato to the Revolution (detail), 1957-66, acrylic and pyroxylin on cloth-lined wood, Museo Nacional de Historia, Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

Unlike Vanegas Arroyo, David Alfaro Siqueiros had no reason to fear Díaz when, decades after Díaz’s death, he placed him in the center of the first portion of an enormous panorama of Mexican history (pictured above). The top-hatted despot is seated, trampling the law underfoot. He is engulfed by women in cinched gowns and big, feathered hats. They dance for the entertainment of Díaz and his ruling elite. These feathered hats are part of the attire of the enemies of the Mexican Revolution.

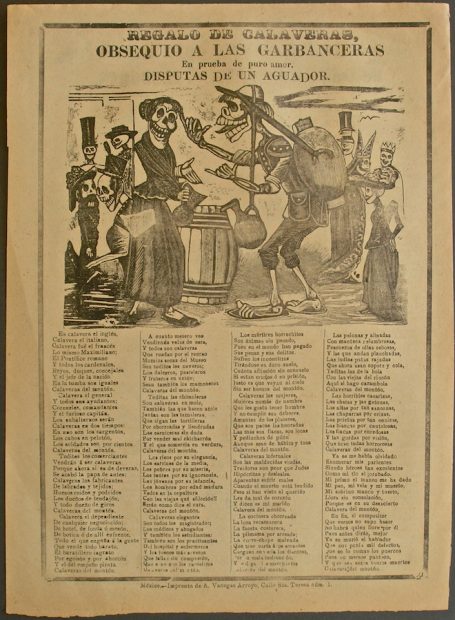

José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), Regalo de Calaveras, Obsequio a las Garbanceras, En prueba de puro amor, Disputas de un Aguador (Gift of Calaveras, Given to the Chickpea Sellers, As Proof of True Love, Quarrels of a Water Seller), photo-relief etching, c. 1905.

The Catrina character and a garbancera make a brief appearance together in a spectacularly bizarre broadside that features strange juxtapositions (both spatially and socially), was well as mannerist distortions of space. Stylistically, this work is later than the Mole broadside and likely before the “Catrina” image.

Before we move on to Rivera’s refashioning of “Catrina,” let us note that the Catrina character in the lower right of this detail (who is apparently standing in front of a pope and a king) is dressed in full bourgeois costume. Thus, like Mrs. Díaz, the two Catrina characters in the Mole and Regalo broadsides wear ensembles that match their hats.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park, 1946-47, detail of lower center, Museo Mural Diego Rivera, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

Rivera Refashions Posada’s “Catrina”

Rivera transformed “Catrina” from an object of ridicule and bourgeois pretension to one of national pride. Just how did he work this alchemy? He put his Catrina in the center of a 50-foot long mural that treats Mexican history, from the Spanish Inquisition to the Revolution. She wears a long, simple white skirt, which is a purposeful fashion faux pas. Catrina should have an elaborate and costly gown, with puffy sleeves and a tightly cinched-waist, like Mrs. Díaz, or like the women on the left side of the detail above. Moreover, a white skirt doesn’t go with a black hat. Nor do white feathers. Rivera enlarged them, largely effacing the European hat (since the Aztecs valued feathers more than gold, their enhanced scale has symbolic significance). Rivera has pulled a sleight of hand: his Catrina has a dress much like that worn by his wife, Frida Kahlo. Though it is European-derived, this type of skirt was worn by indigenous women from Tehuantepec. They are among the most admired Mexican costumes, though more for the colorfully embroidered blouses than for the bland skirts. Kahlo wore Tehuana costumes in most of her self-portraits to signal her affiliation with the indigenous. Many of them are in the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City. A big, bourgeois hat such as this one was not something Kahlo would have worn. Catrina’s dress matches her white, skeletal visage, as well as the ostrich feathers and the artificial flowers in her hat. This dress stands in stark contrast to the colorful dresses because it is meant to signal affiliation with the indigenous — as well as with the skeletal.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park, 1946-47, detail of Catrina’s feather boa, Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

The Tehuana skirt is a subtle invocation of the indigenous. More importantly, Rivera equipped his Catrina with a feather rattlesnake boa. This connects her with the Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl (the feathered serpent), who represents fertility, culture, learning, and the arts. Its rattle looks like stone, which also connects Catrina with the Aztec goddess Coatlicue (she of the serpent skirt). Rivera likely had in mind the monumental stone statue currently in Mexico City’s Anthropology Museum (which is usually identified as Coatlicue), as well as the many stone sculptures of rattlesnakes made by the Aztecs. Coatlicue is the most fearsome and imposing statue that survives from the Aztecs — or from any culture, for that matter. Having given birth at the moment of her decapitation, Coatlicue represents both life and death (her newborn child immediately avenges her murder).

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park, 1946-47, detail of Catrina’s head, Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

The association with Coatlicue is further underscored by Catrina’s face. Like Coatlicue, she has fangs. This attribute links her to snakes (even Catrina’s feather boa snake has fangs), and further identifies her as a devourer of life. The area around Catrina’s mouth is ringed with blood. At the same time that it invokes death, it also recalls red lipstick and the primal impulse to signal sex appeal. Thus the red ring around her mouth links Catrina with the forces of life as well as those of death. If one looks deeply into Catrina’s eye sockets, one sees that they are inhabited by living eyes that peer back at the viewer. This aspect is also evident in Posada’s “Catrina” (though he evinces no interest in pre-Hispanic art). Death is but an uncanny mask for the living.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park, 1946-47, detail of lower center, Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

Rivera represents Catrina as both dead and alive, because she is the embodiment of Mesoamerican dualism. Her belt buckle is a gold ollin emblem, which stands for movement and thus for life. (It is also a joking reference to Tehuana woman, who loved gold and incorporated gold coins into their jewelry). The ollin glyph at the center of the Aztec Stone of the Sun also serves as a reminder that movement (in the form of earthquakes) will bring about the end of the current world. With one hand, Catrina grasps Diego Rivera, who is here depicted as a disheveled and mischievous young man. His youthful state suggests life and regeneration. A frog (Rivera’s nickname) emerges from one pocket; a snake (arguably the most potent Mesoamerican symbol) emerges from another pocket. These potent life forces are balanced by the vulture (another devourer and emblem of death) on the handle of his umbrella. Rivera’s much younger and much smaller real-life wife is depicted as an adult; Kahlo looms behind him, invoking a maternal presence. She holds a yin-yang symbol in a claw-like hand. The latter connects her with Coatlicue and other supernatural beings. The yin-yang emphasizes the unity of life and death: it is often used to explain the Mesoamerican concept of dualism.

James Maffie points out that for Mesoamericans “Life and death are mutually arising, interdependent, complementary, and competing aspects of one and the same process … Life without death is impossible, just as is death without life. Life contains the seed of death; death, the fertile, energizing seed of life. Life feeds off the death of other things, and so has a negative aspect. Death feeds life, and so has a positive aspect. In short, life and death are ambiguous: both positive and negative.”

For Mesoamericans, bones were powerful reservoirs of vital life forces. The Aztecs believed that the god Quetzalcoatl reanimated the human race by sprinkling his blood on human bones stolen from the underworld. Maffie adds that Mesoamerican dualistic masks, which are half bone and half flesh, are “neither-alive-nor-dead yet at the same time both-alive-and-dead.” The same analysis can be applied to Rivera’s Catrina. The blood on her face represents devouring death as well as the reanimating force of blood on bone.

Catrina is goddess, mother, daughter, wife, and muse. She is Coatlicue, garbed in Rivera’s unique and strange mélange of turn-of-the-century drag. She is a protective and reassuring mother to Diegito. She is Posada’s progeny: their arms are linked, and Posada also holds her left, red-tipped hand (though he stares at La Revoltosa, a popular theater performer, who is arrayed in a bright yellow dress). Posada is formally attired, like a proud father who is about to hand his white-gowned, prized daughter to a worthy mate. Through Rivera’s rehabilitating alchemy, Catrina becomes the living embodiment of pre-Hispanic culture, and as such, the ultimate muse of modern Mexico as it seeks to break free from the crushing, colonizing, genocidal grasp of European influence (here understood as direct Spanish colonization and neo-colonial foreign investment, political manipulation, and military and cultural invasion). Rivera, the brilliant and boastful mythifier supreme, claims a triple connection. Catrina, presented as the distilled essence of Mexican tradition, is his mother, his muse, and his bride. She is the goddess that Kahlo incarnates in human form. Moreover, Rivera positioned Posada as the head of the modern Mexican school. Through the mediation of Catrina, the goddess he fashioned specifically to connect the past to the future, Rivera literalizes an intimate connection to Posada as he lays claim to his legacy as the anointed, hand-holding heir.

Later Catrina Images

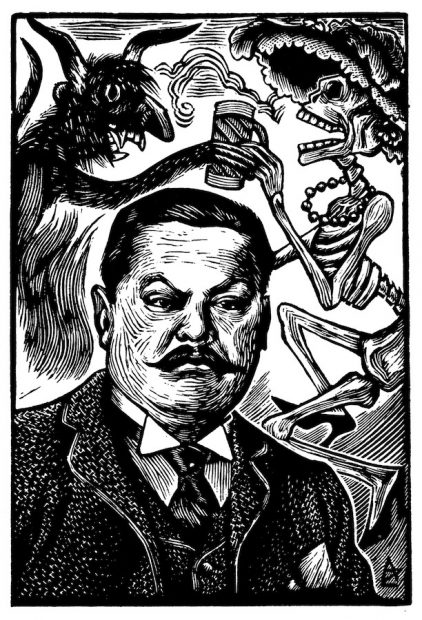

Ángel Zamarripa (1912-1990), Portrait of Posada with Catrina and the Devil, 1952, periodical cover, licensed by Dover Books.

Perhaps Ángel Zamarripa took the following lines from the Garbancera broadside to heart: “There are beautiful garbanceras,/ corseted and high-heeled/ but they will be calaveras/ calaveras of the masses.”

In any case — unlike Rivera — Zamarripa dressed his Catrina consistently, though she wears nothing but her hat, a necklace, and high heels as she shares a beer with a Posada-style devil, which is engulfed in flames. Judging by their smiles, they appear to be having the time of their lives.

Felix Nieves, Catrina figure being rendered in chalk, 2009, Zocalo, Mexico City, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

In art, Catrina is often replicated rather faithfully from Rivera’s mural.

Linares Family, recreation of Rivera’s Alameda mural in papier-mâché with Ruben C. Cordova seated in foreground, 2014, Dolores Olmedo Museum, Mexico City, photograph by Deborah Richmond

The most impressive replication that I have seen is the papier-mâché version at the Dolores Olmedo Museum in 2014. This museum consistently mounts the most extraordinary Day of the Dead altars. (See my Guide to Day of the Dead in Mexico City.)

In real life, impersonators almost always go full bourgeois, completing their costumes with beautiful gowns and coats. (They sometimes even dye their dogs to match their ensembles.)

Catrina impersonator, 2009, Museum of the First Printing Press, Mexico City, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Catrina impersonators have long favored a color scheme of black, purple, and magenta. This impersonator at the Museum of the First Printing Press is passing out candy to visitors. Her Quetzalcoatl head is made out of papier-mâché, which is a very rare material for this feature. Impersonators usually omit the Quetzalcoatl head and the Ollin symbol. They tend to wear opulent gowns (not Tehuana skirts) with opulent boas. They also lack fangs and blood-smeared faces. Moreover, impersonators usually add European objects that neither Posada nor Rivera depicted, such as vintage-looking fans, purses, parasols, and jewelry. Contemporary Catrinas usually eschew all of the indigenous emblems that Rivera provided to his Catrina. These were, of course, precisely the features that transformed a European wanna-be into a specifically Mexican character. Consequently, impersonators look like they just stepped out of the Porfiriato. The hat alone is enough to crown a Catrina. After all, it sufficed for Posada.

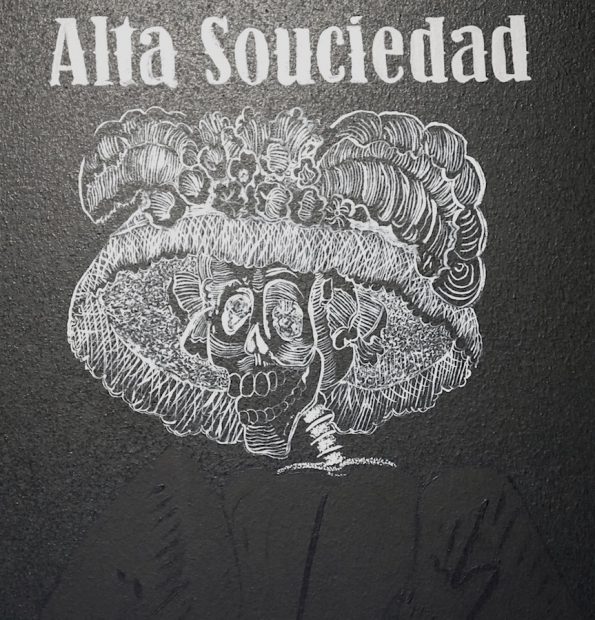

Roberto Gonzalez, DreamStack Series: Adicto Al Peligros (Addicted to Danger) detail of upper center, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 96 x 40”, collection of the artist, The Day of the Dead in Art exhibition, Centro de Artes, San Antonio, photograph courtesy of the artist

In this detail by Chicano artist Roberto Gonzalez, an expressively demented Catrina head is rendered in white-on-black, recalling the “negative” image of a printing block. This painting seeks to explore Posada’s unconscious. Gonzalez posits Catrina as a false, self-delusional being. The punning inscription “Alta Souciedad” transforms the phrase “alta sociadad” (high society) into “high trash.”

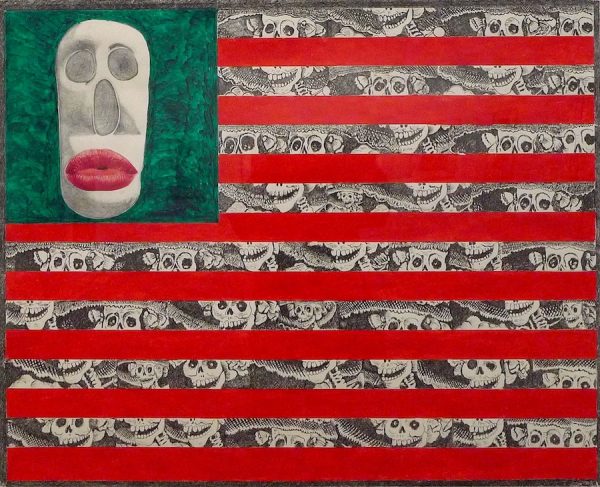

Ruben Trejo (1937-2009), untitled (flag with Catrina stripes), 2003, 34 x 42”, mixed media, collection of Gil Cardenas, The Day of the Dead in Art exhibition, Centro de Artes, San Antonio, photograph Ruben C. Cordova

I haven’t seen a stranger use of Catrina imagery than in Chicano artist Ruben Trejo’s untitled protest-death-flag, which substitutes undulating ribbons of Catrina heads for white stripes. The strange eyes that peer out of the skull are particularly haunting.

Ill. #22: Sugar Skull Catrina, 2009, detail of Altar on bar of restaurant, Bellas Artes, Mexico City, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Catrinas can be made of any substance. On a single altar, there might be dozens of Catrinas, made of sugar, ceramic, wood, metal, etc., as was the case with this altar at Bellas Artes in 2009. Like statues of protective saints, there can never be too many Catrinas.

Bauhaus-inspired Catrina impersonator, 2017, National Museum of Art, Mexico City, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Day of the Dead traditions constantly evolve. In 2017, I happened upon a Day of the Dead fashion show at the National Museum of Art. The strangest Catrina impersonator apparently combined a Bauhaus costume with a simple Mexican petate (mat). Her outfit was so unyielding that several calavera wranglers had to help her up the stairs. The calavera on stilts had a much easier time navigating them.

Butterfly Catrina impersonator, 2017, National Museum of Art, Mexico City, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

I thought this Butterfly Catrina impersonator was one of the most moving costumes in the fashion show. Butterfies in contemporary Mexican and Chicano art are recognized as emblems of emigration. They also invoke the menace of climate change.

“Sofia, the monumental Catrina,” 2007, papier-mâché, Mixquic, Mexico, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

“Sofia” was created by 3,000 people in 2007 in the municipality of Tecámac in the Federal District. At 8.1 meters high, it is said to be the tallest papier-mâché sculpture in the world. It’s definitely the biggest Catrina that I have seen. It was exhibited at the entrance to the town of Mixquic in 2010. In this picture, two tourists read the label in astonishment.

Catrina competitions have become the rage, both in statue size and quantity of impersonators. Guinness world records are set on a regular basis. The biggest recent wrinkle is the Day of the Dead parade made for the James Bond film Spectre (2015). Mexico liked it so much they made it into an annual event, starting in 2016. Newscasts linger on Catrina imagery, and often use a Catrina float as a background image.

Why did Catrina become so popular, so central to Mexican artistic and cultural identity? There are many factors. Mexican modernists, including several muralists and printmakers, made Posada into their primary artistic ancestor figure. Rivera worked a special magic in his Alameda mural, where he, Posada, Catrina, and Kahlo hold central stage. Annual Day of the Dead commemorations were — and continue to be — held at museums devoted to Rivera and Kahlo (Anahuacalli and the Kahlo Museum). These were formative in the development of urban celebrations of the holiday. Rivera, Kahlo, and Catrina made for a deadly threesome. Rivera was the pre-eminent Mexican artist for many decades, until Kahlo superseded him, which means that neither artist was ever very far from the limelight. Rivera’s Alameda fresco was recently included in a video series by Sotheby’s called “The Most Famous Artworks in the World,” in the company of such masterpieces as Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas.

Finally, in the Spanish language, death is a woman. Since the word death (la muerte) is feminine gender, it is natural to conceive of a female death figure. La Parca, the Grim Reaper image that the Spanish brought to the Americas, was regarded as female. In addition to Catrina, other female death figures include Santa Muerte (basically the Grim Reaper in female drag turned into the “saint of last resort” in folk Catholicism), and, in New Mexico, Doña Sebastiana (a female Grim Reaper who uses a bow and arrow and rides an oxcart).

Therefore, it is not surprising to encounter Santa Muerte statues wearing Catrina hats. Mexico, after all, is the land of syncretism.

****

Let’s summarize our journey. An image created by Posada as a satire on bourgeois fashion was used in a Vanegas Arroyo broadside to brutally attack working-class women. Rivera rehabilitated and nationalized the Catrina image by endowing her with indigenous features. Even when shorn of these indigenous components, Catrinas still serve as nationalistic emblems, though, in terms of fashion imagery, they are basically fin de siècle European bourgeois women in skeletal whiteface. While discussing these paradoxes with artist Roberto Gonzalez, he replied: “I am not surprised. Since the conquest, we as a people have been conditioned to deny our indigenous selves and to prefer everything European.”

While Posada and Rivera had pared Catrina down to the bone, contemporary impersonators have become accessory-laden clothes horses. But we can be certain that there will be more twists and turns in Catrina’s story. Her powers seem to be growing. Referring to Catrina as “Mexico’s grand dame of the dead” (and she certainly dresses like one) the Chicago Tribune quotes a Mexican-born teacher who declares: “The Catrina is something spiritual.” The current Wikipedia entry on Day of the Dead informs us that Catrina somehow corresponds to the “Lady of the Dead,” to whom festivities were allegedly dedicated in the distant past. The Google Doodle text preposterously claims that Posada’s “Catrina” was “inspired by Mictecacíhuatl” (Wikipedia’s Aztec Lady Death). Perhaps next someone will propose that Mrs. Díaz was the transitional goddess between the Lady of the Dead and Catrina.

Jack-o’-lantern Tzompantli (skull rack, used to display the heads of sacrificial victims), 2009, Mixquic, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

In the figure of Catrina, we are currently witnessing a recrudescence of the bourgeois, but this might be followed by a revival of the indigenous, symbolized by the Jack-o’-lantern tzompantli pictured above.

****

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than thirty exhibitions. His “The Day of the Dead in Art” at Centro de Artes (the former Museo Alameda) in San Antonio in 2019-2010 featured more than 100 works by more than 50 artists from Mexico and the US. This revisionist assessment of Day of the Dead began with Posada and his contemporaries and extended to contemporary artists, some of whom made works commissioned for the exhibition.

8 comments

Excellent article. Thank you so much.

You are most welcome, Robert. I enjoyed following all the twists and turns in the Catrina saga.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WiInHaPcoiU&t=369s

Un gusto leer un trabajo tan completo sobre la obra. Fue mi tesis doctoral

Rubén C. Cordova ojala y podamos contactar y dialogar sobre el tema.

Gracias, Miguel. El editor me enviará su email.

This article is incredible. Thank you so much.

The evolution of the Catrina is particularly interesting to me as I look into my own family history in Mexico City. Much gratitude for your thorough research and skilled storytelling. Thanks again

You are very welcome, Tanya. Catrina’s origins are very complex, and her further adventures are endlessly fascinating. I write an article every year on Catrina to address this ongoing cultural phenomenon. I’ve already written and submitted Catrina IV for publication, so it will be out in a few days.

I was trained in Chinese art history on a graduate-student level. In my entire life, I have never read and seen such thorough, convincing, enthralling scholarship on a subject that is not within my “field”. I am no longer a specialist in Chinese art history, but many years ago published a specialized study of an American poet and her acquired heritage of East Asian models for her poetry. I have never lost, in the intervening years, my interest in art history and, while less acquainted with Mexican art history, I found your article to be fascinating, thoroughly researched, illustrated perfectly, and so compelling, that I felt that I needed to congratulate you and show my appreciation for your paramount scholarship on a fascinating subject and your incisive analysis of all you have gleaned from the subject. Quite literally, I am astounded by your scholarship. Thank you for making this study available. I so appreciate your efforts!

Thank you for your kind comment, Cynthia. Day of the Dead is an area plagued by terrible misinformation, so I have been trying to provide a sound basis for future scholarship in my articles and other writings. I am particularly fascinated by Catrina’s complex origins and her growing popularity. I have written some other Day of the Dead articles for Glasstire, including an article on Catrina every year.