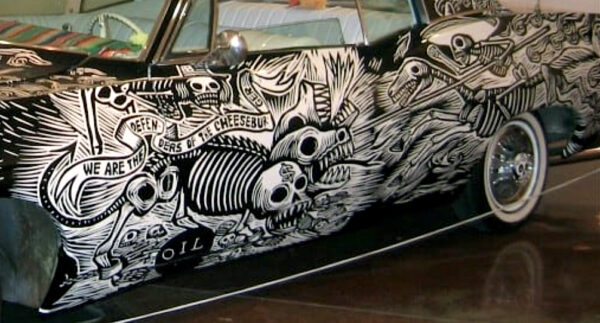

Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, Muertorider (1968 Chevy Impala, detail of Catrina image on hood), 2006, car, auto paint, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: The Guardian.

This is the third in an annual series devoted to all things Catrina. In 2019 I wrote “José Guadalupe Posada and Diego Rivera Fashion Catrina: From Sellout to National Icon (and Back Again?).” Click here for an explanation of how the skeletal woman in a big hat was created by two of Mexico’s greatest artists, and how it became a somewhat paradoxical national icon. In 2020, “Catrina Mania!” further charted this international phenomenon. (These articles are referenced below as Catrina I and Catrina II.)

Monumental Catrina, 5,700 people, Plaza de la Patria, Aguascalientes, October 7, 2013. Photo source: Blog Aguascalientes

As is evident in Catrina I and II, Catrinas can be fashioned out of anything. Even — like Soylent Green — people!

Monumental Catrina, 5,700 people, Plaza de la Patria, Aguascalientes, October 7, 2013. Photo source: Flickr/Gobierno Aguascalientes

In the city of Aguascalientes, the birthplace of Catrina’s originator, José Guadalupe Posada, 5,700 people formed an enormous black-and-white Catrina by donning either black or white t-shirts emblazoned with an image of Posada’s print. This brings up an important point: pixels can be people, too.

Monumental Catrina, 5,700 people (detail of about 25 people, including the governor of the state of Aguascalientes), Plaza de la Patria, Aguascalientes, October 7, 2013. Photo source: screen grab from Nuestra Visión Noticias video.

Most of the people who comprised this monumental Catrina were high school and college students. The governor of the state of Aguascalientes (he is waving in the above photo) and his cabinet also participated in this grand event. Click here for the Nuestra Visión Noticias video.

Monumental Catrina, thousands of potted marigold flowers, Taxco Plaza, Guerrero, Mexico, 2015. Photo source: Facebook.

Another memorable monumental Catrina was also fashioned out of “living” forms in 2015, when 6-7,000 potted marigold flowers were arranged in the form of a Catrina in the square of the Taxco cathedral.

Floral tapestries made with potted plants instead of flower clusters and petals, such as for this Catrina, have a more pronounced three-dimensional character. This helps make them legible from a considerable distance.

The foundational drawing, which took 6-8 hours to make, closely follows Posada’s original (as did the Aguascalientes human mosaic discussed above). It then took 8-10 hours to arrange the flowers over the drawing. Click here for a video by Landa Visión of this Catrina, which was designed by María Inés Gómez Pineda and Willy Hairo Rodríguez Gómez.

Monumental Catrina, 17,000 potted marigold flowers, Taxco Plaza, Guerrero, 2021. Photo source: Taxco Facebook.

This year, Taxco produced another florid Catrina, one that is unusually large and that represents a significant departure from Posada’s design. Catrina is still recognizable, however, by virtue of her large hat. Though it lacks ostrich feathers, her hat is endowed with elaborate flowers. She is facing to her left instead of her right, and she is smiling broadly while she tips her hat with her left hand. This Catrina has been given a large collar, which seems to slice through her skeleton, displacing her ribs to a lower level. She has no blouse or skirt, unless we interpret the Taxco banner as an article of clothing.

According to Adriana Covarrubias in an El Sol de Acapulco article on October 24th, the first version of this year’s flower tapestry was heavily criticized by the public, though there’s no mention of why it was criticized. (Was it, perhaps, a hatless Catrina?). The mayor of Taxco, Mario Figueroa Mundo, ordered the first version to be dismantled. He said the resulting second version of the floral tapestry is truer to Mexican traditions for Day of the Dead. It was also designed by María Inés Gómez Pineda and Willy Hairo Rodríguez Gómez. When the celebration is complete, the potted flowers will be given to people to take home.

Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, El Muertorider (1968 Chevy Impala, in San Francisco), 2006, car, auto paint, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: John Jota Leaños/Vimeo.

Like the previous two works, the next Catrina is also ambulant. It’s totally dope and full of horses. It really moves, and it has a one-of-a-kind entertainment center. When this Muertorider (Deathrider), a ’68 Impala customized by Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, was featured in The High Art of Riding Low at the Peterson Automotive Museum in L.A. in 2017, it was one of four lowriders discussed in the Guardian.

The car was manufactured in Los Angeles for the 1968 model year. It is, as California-based artist John Jota Leaños explained to me this year, an “homage to the California driving experience,” including the lengthy road trip, cruising culture, etc. Leaños added that this experience “includes the unfortunate history of the statewide policing of lowrider culture since the 1970s in the form of anti-cruising ordinances, illegal curfews, and restructuring city streets which in effect delegated this grassroots cultural expression to car shows and trade industries.” These actions, said Leaños, have relegated the lowrider to “the museum/mausoleum as a dying and/or dead cultural artifact.” Unlike most custom cars in museums, El Muertorider is intentionally imperfect rather than “clean and pristine.”

A self-taught woodcut artist and printmaker, Artemio Rodríquez is a Mexico-based artist who worked for an extended period of time in California. He admires Posada so much that he wrote a book about him: José Guadalupe Posada: 150 Years (2003). (I included several of his works in my exhibition The Day of the Dead in Art at Centro de Artes in San Antonio in 2019-20.) In addition to the image of Catrina on the hood, several of the images that appear on the Muertorider derive from Rodriguez’s reworkings of other prints by Posada. The rear end of the car depicts the history of colonialism in California in a more modern style that also reflects Posada’s influence.

Leaños, a new media and installation artist, had already purchased this 1968 Chevy Impala in 2006, when he met Rodríguez at a Creative Capital Foundation event in San Francisco. Leaños planned to use the car as part of his Imperial Silence: Una Opera Muerta, a project with four acts. The piece was inspired by events that took place in 2004, when he was on faculty at Arizona State University. Leaños created a Day of the Dead poster that considered fallen soldier and ex-Arizona football star Patrick Tillman. It resulted in censorship, death threats, and a classroom investigation.

These experiences led him to explore the history of the silencing of dissent during wartime, and resulted in a four-act new media opera and installation. The first two acts are comprised of animations that played at film festivals in 2006 and 2007. The third act, “¡Radio Muerto!,” features animations and a thirteen-hour radio project. Leaños wanted to have a “real” auto/audio component, and from this desire, “El Muertorider was born.” The opera’s fourth act is “DNN: Dead News Network,” an animation that presents news from the perspective of the dead.

Rodríguez and Leaños restored, measured, and designed the car with motifs appropriate for the themes of the Imperial Silence opera. Rodríguez made woodcuts, scanned them, and printed them on a vinyl-like substance. The artists painted the white car, applied the vinyls, painted the car black, and then removed the vinyls. They then outfitted the car with a hi-fi stereo, a DVD player, a screen, and an iPod with the radio program.

The Catrina image on the hood, in the manner of Day of the Dead altars, commemorates the victims of Hurricane Katrina, a Category 5 storm that caused great suffering and more than 1,800 deaths when it hit New Orleans in August of 2005. The inscription “LA KATRINA” beneath the image makes this dedication explicit. As Leaños notes, the Catrina image “speaks to the folly of humans and our class-based hierarchies.” He emphasizes that El Muertorider’s Katrina specifically addresses “the class-based environmental racism that occurred in New Orleans.” Leaños points out that what appear to be flowers surrounding Katrina on the hood are actually satellite images of the hurricane itself.

Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, Muertorider (detail of three-headed beast chained to oil, attacked by skeletal rider with lance on driver’s side), 2006, car, auto paint, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: Richard Harris artwork archive.

The Muertorider also commemorates the victims of war. It makes specific reference to George W. Bush’s Iraq War, which began with a U.S.-led invasion in 2003 that was based on false claims that Iraq possessed “weapons of mass destruction.” Despite Bush’s speech aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, during which he stood under a banner that read “Mission Accomplished,” the U.S. occupation of Iraq lasted until 2011.

On the driver’s side of the Muertorider, a three-headed consumption beast (an updated synthesis of the beast of the Apocalypse and Cerberus, the hound of Hades) is chained to a black ball marked “oil.” A ribbon banner above it reads: “we are the defenders of the cheeseburger.”

The forehead of one of the monster’s skulls is inscribed with a dollar sign; another has a forked tongue, and the third breathes fire. The beast is being attacked by a skeletal rider with a Mexican hat who wields a lance, a reference to Posada’s Don Quixote print.

Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, Muertorider (“War is Money” detail), 2006, car, auto paint, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: Dope Rider blog.

The passenger’s side door features an illustration that reprises a Rodríguez print of a skeleton riding a skeletal, fire-breathing horse that has a rocket protruding through its neck. The figure wields a pistol in his right hand and a bag of money in the other and bears a banner that reads “War is Money.” Victims of strife are scattered below him.

Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, Muertorider (“Burning Wagon” panel), 2006, car, auto paint, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: Dope Rider blog.

The car’s trunk features the primary colonial routes utilized by the invaders of California: 1) El Camino Real (now US Highway 101) used by the Spanish; 2) the “Wagon Trails” that served the Gold Rush and Manifest Destiny; 3) the “Iron Snake” Transcontinental Railroad; 4) Route 66, which brought car culture to Los Angeles.

On the right, a large Native American skeleton holds a bow and a captured wagon wheel. He is balanced on the left by a Mexican campesino with a plow. They bear witness to what Leaños calls the “carving out of the land,” and the beginning of the “ownership society” that privatized space. A burning wagon image, a covered wagon attacked by flaming arrows, is a representation of Leaños’ media collection. A settler in cowboy boots holds a pistol, while a woman runs towards the wagon with buckets of water.

Artemio Rodríguez and John Jota Leaños, Muertorider (view from above), 2006, car, auto paint, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: John Jota Leaños.

The top of the car features a skeletal Muertuvian Man (the Dead-truvian Man), which is a parody of Vitruvian Man — Leonardo da Vinci’s ideal man — which he originally inscribed within a square and a circle. Leaños and Rodríguez added another square, set like a diamond, to reference “the four directions” as “an Indigenous Xicanx critique and manifestation of European settler notions of science, knowledge, and perfection.” The rays that emanate from him were added as a formal design element, but could be interpreted as ancient wisdom radiating from the Muertuvian Man’s heart.

Rodríguez and Leaños have incorporated a Catrina image into a complex historical ensemble that stretches from the dawn of the European colonization of California to the contemporary repression of lowriding. Within the museum setting, visitors could listen to and interact with “alternative and independent radio programming,” which, said Leaños, enabled “the dead lowrider” to become “a reflection of living culture.”

El Muertorider is simultaneously a celebration of the history of cruising and lowriding, a critique of “the policing and silencing of grassroots cruising culture in California,” and a museum-piece epitaph on the cruising experience. As a concluding legacy of colonialism, its final destination is the museum, not the open road. The high-tech lowrider’s mobile art installation, which includes an LCD movie screen and the “¡Radio Muerto!” curated radio dial with content from local youth, artists, writers, and everyday people, serves as a simulacrum and as a requiem for the open road and the car culture that it engendered.

Carlos Barberena with installation at the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2020. Photo source: Courtesy of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago.

Carlos Barberena is a self-taught Nicaraguan artist who is currently based in Chicago. When I first saw these photographs of his installation at the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, I thought his illustrations were vinyl decals. Instead, they are linocut prints wheatpasted onto the museum’s walls.

In 2020, the museum invited Barberena to create a mural for its Sólo un poco aquí: Day of the Dead exhibition, curated by Dolores Mercado. In addition to this mural, Barberena also created an installation honoring essential workers.

While Barberena follows Posada’s hat and pair of ostrich feathers very closely, he transforms the rest of the image. His updated Catrina depicts a young woman of the “sugar skull” variety: her face is painted white with decorative devices, including a spider web on her forehead, without an attempt to imitate or replicate the bone structure of her skull.

Carlos Barberena with installation at the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, 2020. Photo source: Courtesy of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago.

Unlike Posada’s original, which features a bald and aged skull, Barberena’s Catrina is a fully-fleshed young woman with long hair. Barberena substitutes a large marigold — the prototypical modern Day of the Dead flower — for the small flowers in the center of Catrina’s hat. (For the many varieties of flowers used by the Aztecs, see my 2019 Glasstire article, “Is Day of the Dead More Indigenous or Catholic?“) Instead of the skeletal neck and upper body and clouds in Posada’s original image, Barberena created an elaborate, scrolled cartouche that frames the young woman and her hat. Barberena’s image is thus simultaneously more modern and more old-fashioned than Posada’s.

Barberena notes in his artist statement that he has lived through dictatorship, revolution, and cycles of repression. He therefore seeks to “counteract the great silence” about repression and to “demystify the ‘foreign’ experience” by bridging all walls and borders. The young Catrina in this installation can thus represent hope, renewal, and life after cycles of death.

Enrique Martinez, Volver, Volver, Volver (Return, return, return), pencil on paper, 16 x 20 inches, 2005, private collection. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

I included this little Catrina-centric Day of the Dead melodrama in my 2019-2020 exhibition at Centro de Artes, but after examining the Muertorider, I realized that I didn’t say enough about her remarkable vehicle. Enrique Martinez, a San Antonio-based artist, calls this horned bull-devil El Diablo. Its hind section is ordinary enough, but its spindly front legs terminate in little hands instead of hooves. It has a gigantic, phallic neck, and a sharp-featured human head with ram’s horns. It floats above the cemetery road it traverses.

This drawing seems to be a Day of the Dead parallel to the theme of the Abduction of Europa. Only this is a love triangle gone bad. The mariachi on the right is the jilted lover, and Catrina waves goodbye to him with his most recent gift, a bouquet of flowers. His outstretched arms convey his shock. The well-dressed figure in the left background is Catrin, who is Catrina’s traditional mate (their names are gender specific words for dandy). El Catrin has utilized candles, incense, and incantations under the full moon to summon El Diablo. The artist says havoc has been unleashed, though he doesn’t specify the fates of his protagonists.

Laurie Lipton, La Catrina: Day of the Dead, pencil on paper, 15 x 10 inches, 2005, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: Richard Harris artwork archive.

Laurie Lipton, a Los Angeles-based and highly gifted depicter of the macabre, made this variation on Catrina in 2005. It was inspired by drawings of the new feminine ideal known as the “Gibson Girl,” created by Charles Dana Gibson in the late 19th century. At the time, women were participating more actively in the public sphere, and Gibson rendered a youthful and athletic idyll. He described her as “the American girl to all the world,” making her the fin de siècle equivalent of the Barbie doll. Unlike Barbie, however, Gibson’s beauties were privileged-class fashion plates that attended the theatre and fancy balls. Lipton has chosen a pose and setting that implies a grand entrance to a formal event.

These busty, heavily corseted women have “hourglass” figures. Appropriately enough for Lipton’s Day of the Dead variation on the Gibson Girl theme, the hourglass is itself a symbol of mortality.

Laurie Lipton, La Catrina: Day of the Dead (detail), pencil on paper, 15 x 10 inches, 2005, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: Richard Harris artwork archive.

Instead of the face of a vivacious young woman, Lipton substituted a wide-mouthed skull. For good measure, she is missing a few teeth and has several holes bored into her skull, implying the passage of time after death.

Laurie Lipton, La Catrina: Day of the Dead (detail), pencil on paper, 15 x 10 inches, 2005, collection of Richard Harris. Photo source: Richard Harris artwork archive.

The Gibson Girl had upswept hair in feathery curls, and was often crowned — like most Catrinas — with a big, feathered hat. Lipton dispensed with the big hair and hat altogether, replacing them with a multitude of interwoven feathers. One might say that Lipton’s Catrina is a hatless Catrina — though I regard her feathers as a virtual hat; the feathers themselves and the artificial flowers in the center clearly reference Posada’s image.

Catrina, modeled by Callisto Griffeth, Catrina Ball benefit for the Mexic-Arte Museum, Austin, 2015. Photo source: Facebook.

Let me close with the magnificent parasol of a hat worn by Callisto Griffeth at the Catrina Ball benefit for Austin’s Mexic-Arte Museum. Catrina Balls are quite a phenomenon; in Catrina II, I included a picture from the Catrina Ball benefit for the San Antonio Public Library Foundation.

Catrina, modeled by Callisto Griffeth, Catrina Ball benefit for the Mexic-Arte Museum, Austin, 2015. Photo source: Facebook.

This is truly a hat that puts most other hats — including those worn by many Catrinas — in the shade.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than thirty exhibitions.