Brandon Maldonado, “The Carriage” (detail of coach), 2010, oil on panel, 16 x 28 inches. All Photographs of Maldonado and his work are courtesy of the artist. All artworks are in private collections, unless otherwise noted.

This is the fourth installment in an annual series of Glasstire articles devoted to Catrina. Click here for Part 1 from 2019, “José Guadalupe Posada and Diego Rivera Fashion Catrina: From Sellout to National Icon (and Back Again?).” It explains how Rivera elaborated the figure created by Posada (of a grinning skull in a big hat) and how Rivera endowed it with indigenous significance. The article also explores various roles Catrina has played in Mexican and Chicano art and culture, beginning with Posada’s broadsides. Part 2, “Catrina Mania!,” and Part 3, “Catrina Mania III,” are further explorations of Catrina-related phenomena in art and popular culture.

Photograph of Brandon Maldonado in the courtyard of the José Guadalupe Posada Museum in Aguascalientes, Mexico, c. 2011. The papier-mâché figure of a skeletal deer with a Frida Kahlo mask is by an unknown artist.

This article focuses on some of the highly varied Catrina figures created by the Albuquerque-based artist Brandon Maldonado (b. 1980). He introduces himself this way on Instagram: “On the side of Marginalized Artists. Folk Art, Outsider Art, Street Art, Lowbrow, Psychedelic, Mexican muralismo. Raised on graffiti. In Nuevo Mexico.” Those are only a few of the allegiances, influences, and sympathies Maldonado forged during an artistic career that now spans more than two decades.

Day of the Dead was a formative area of exploration that led Maldonado to become an artist. The figure of Catrina serves as an important, recurring theme in his work. Maldonado explains how his artistic career began:

I have always been drawing skulls and such. Very early, as an eight-year-old, it was more in line with Powell Peralta skateboard graphics, like the Ripper character, and then graffiti stuff. The possibility of becoming a professional artist as a career was kind of taken from me when my dad refused to co-sign the loan for an art school in Denver. So I found myself in a community college studying to be a Spanish teacher. In a Spanish class, looking at the Día de los Muertos imagery in the textbook, I began drifting off into my art dreams. I sketched out calaveras while the Professor was lecturing. I must have thought they were pretty good, because I just kept doing them week after week from that point on. I wanted to put them out into the world for people to see.

Back then, in 2001, there was hardly any Día de los Muertos imagery to be found in Albuquerque. I was trying to find a place to sell my posters and books and t-shirts, and there were only a couple of shops. Mexican import shops to be exact. So that’s where I set up business. Somehow, these days, people have confused Mexican culture with New Mexican culture. You can find tourist shirts that say “Albuquerque, New Mexico,” with some sort of Muertos imagery. I don’t really like that because Día de los Muertos is really something that comes from deep in Southern and Central Mexico. Let’s give credit where it’s due.

For an introduction to Maldonado and his disparate sources, which include traditional religious art from New Mexico, the self-taught artist Martín Ramírez, and Pablo Picasso, see my 2022 Glasstire exhibition review “Crossing Borders: the Work of Ricardo Islas, Brandon Maldonado, and Vicente Telles.” Maldonado’s website can be accessed here.

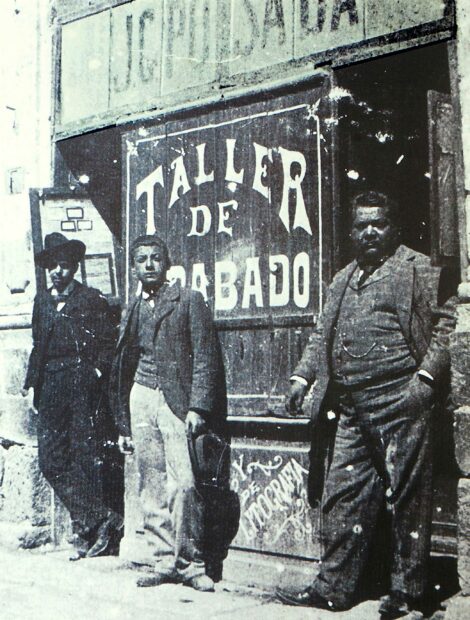

Photograph of José Guadalupe Posada (right) in front of his shop, c. 1910. Photograph: The Posada Art Foundation.

I asked Maldonado how he became familiar with Catrina, and why this image cast such a spell over his art. He replied that he was inundated with Catrina images throughout his early life as a student:

My fascination with the Catrina character began in elementary school. And it was reinforced in middle school and high school. Whenever a teacher gives a presentation on Día de los Muertos, they undoubtedly reach for the Catrina image. After all, it is José Guadalupe Posada’s most popular image. Is it his best? I’m not certain. But in its simplicity and clarity, it is very easy to soak in and absorb. Once you see that face and hat, you will never forget it.

The Catrina image is so ubiquitous that Maldonado compares it to propaganda posters: “Its almost like Shepherd Fairey’s Obey imagery. How often do you see Catrina without trying to seek her out?”

Perhaps no one would be more surprised by Catrina’s omnipresence in contemporary culture than its creator. Posada, who died in 1913, was a low-status artisan who worked very quickly. The trade he practiced was not one that brought fame or prestige, such as that achieved by many modern artists. Posada probably did not expend a great deal of time or thought when he made the Catrina image around 1910. It was never published during his lifetime, for reasons I explain in Part 1. So Posada would be amazed to learn that the face he created — but never saw as a finished product — is now plastered on every conceivable object in many parts of the globe.

Born in Denver in 1980, Maldonado lived in Colorado until he was six, when his family moved to Albuquerque. As noted above, Maldonado is a self-taught artist who came to art through various experiences, including graffiti. He has a bachelor’s degree from the College of Santa Fe in Humanities, where he concentrated in Philosophy and Religion.

Maldonado is stimulated by travel: he has been visiting Mexico since he was in high school, and he has also traveled to Europe. Maldonado has also spent two-year sojourns in Denver, Taos, and New Orleans.

Maldonado’s trips to Aguascalientes, Posada’s birthplace, were particularly memorable. He recalls that in his early thirties he made several visits, which became Posada pilgrimages. Maldonado recalls that when one comes from the airport, a big Catrina billboard “greets you as you enter the city.”

This monumental sign made a big impression on Maldonado. The experience of seeing it over and over again gave him the notion that Catrina has become “the ultimate Gringo souvenir.” It inspired the artist to make a piece called Gringo Souvenir (discussed below).

Photograph of the printing press used to make some of José Guadalupe Posada’s prints. Photograph: José Guadalupe Posada Museum, Aguascalientes.

As Posada’s birthplace, Aguascalientes appropriately houses the José Guadalupe Posada Museum, which was opened in 1972. Situated in a former cloister adjacent to the Church of El Señor del Encino, the museum owns many of Posada’s prints and plates, as well as a press that was used to print some of the images he created. Maldonado reflects on the experience of seeing this historical object: “it was very moving for me to connect with the original press.”

Maldonado also notes: “sadly, sometimes the social commentary Posada embedded in the piece gets lost on people.” He believes that since Posada “was a political cartoonist, there is no doubt in my mind he was making commentary on the rich not being able to carry their riches and posh-ness to the grave.” For Maldonado, Posada’s Catrina “is great on different levels — not just visually — but as a socio-political statement as well.”

For an overview of Posada and his legacy (about which many misconceptions abound), see the first sections of my exhibition catalog The Day of the Dead in Art (San Antonio: Centro de Artes, 2019). (Click here for a PDF of the catalog.)

Maldonado appreciates the powerful narratives that Posada creates in his prints. He also has some rather traditional ambitions for his own work: “I pick up my paint brushes with hopes that my art can serve as a vehicle for inspiration, consolation and peace for the viewer, in the way paintings of the past once did.”

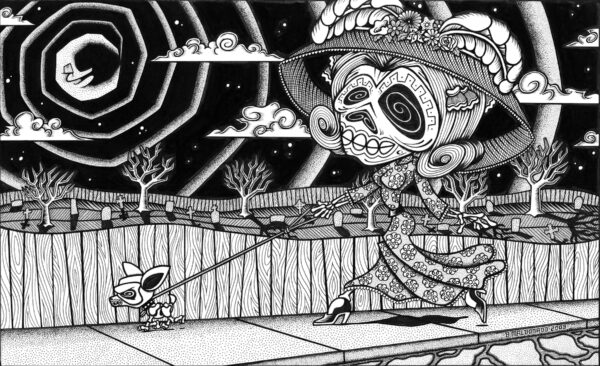

Brandon Maldonado, “La Catrina de la Noche,” 2003, ink on paper, 11 x 17 inches.

La Catrina de la Noche is Maldonado’s earliest Catrina image, made when he was 22 years old. The self-taught artist did not yet know how to paint, though, as noted above, he had made numerous drawings in this graffiti-influenced style that treated Day of the Dead imagery. Maldonado, who is color blind, was heartened to discover the example of Posada, who created powerful images without using color. Maldonado recalls that he had once inadvertently made a green cow, which opened him to ridicule from his fellow students.

Posada’s prints were a major source of inspiration for Maldonado’s early works. He enjoyed the challenges and the limitations of “using only pens to create the illusion of space.” Ink is an unforgiving process, since mistakes cannot be corrected. Once the ink has been applied to the paper, it is there for good, sometimes resulting in “an unfixable mess.” But when this process works well, it produces stark and dramatic effects, as in this piece, with its bold undulating and curvilinear forms.

Brandon Maldonado, “La Catrina de la Noche” (detail of lower section), 2003, ink on paper, 11 x 17 inches.

In La Catrina de la Noche, Catrina is walking her chihuahua, which must be cruising at a rapid clip. Catrina is taking large strides, but she is still trailing behind the little skeletal canine, which strains at its leash. Catrina casts a thin, undulating shadow that resembles a pair of lips, appropriately blackened for Day of the Dead.

Like its master, the Chihuahua has white spirals in its jet-black eye sockets.

Brandon Maldonado, “La Catrina de la Noche” (detail of moon and spiral rays), 2003, ink on paper, 11 x 17 inches.

Spiral forms, in fact, are preeminent, defining features of the ink drawing. Most dramatically, the rays that emanate from the somnambulant moon take the form of an immense, angular and eccentric spiral that grows in size and intensity as it emanates outward into the night. Small dots within this white spiraling form function as halftones that mediate between the oppositions of white and black. This immense spiral endows the drawing with pictorial depth, while its jaggedness also conveys a sense of instability and potential hazard.

Spirals also occur at the tops of the clouds, inside Catrina’s nostrils, and in the ends of her bobbed hair.

Maldonado also had this composition laser-carved onto wooden panels. He explains how this came about:

When I was living in Denver around 2012, I knew a guy that had a laser engraving machine. And I had him burn out an edition of ten images of La Catrina de la Noche on wooden panels. He painted the cradled wooden panels black before he began burning the images. When he was finished, they looked like hand-carved woodblocks that were blackened by ink from printing. So I’ve never actually carved a woodblock image, in the true sense, but these sure looked real. Sometimes I try to emulate the look of the technique by scratching into my ink drawings. But that’s just a way of faking it.

Maldonado hasn’t made editions of prints himself because the stress would be too great due to injuries he suffered while practicing martial arts.

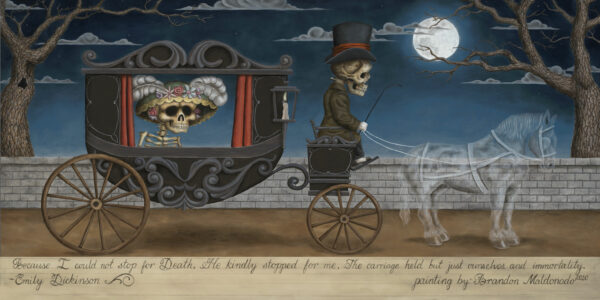

Brandon Maldonado, “The Carriage,” 2010, oil on panel, 16 x 28 inches.

Because I could not stop for Death,

He kindly stopped for me;

The carriage held but just ourselves

And immortality.

– Emily Dickinson

Maldonado has always admired Emily Dickenson’s (1830-1886) poem “Because I Could Not Stop for Death.” The first verse is copied above. (The complete poem can be accessed here.)

Maldonado regards this poem as a kind of visual text that “creates a vivid image” seemingly implanted “in the ‘mind’s eye’” of the reader. Consequently, it took little effort for him to “channel this image from my mind to the painting surface.”

Catrina is alone in a carriage. In fact, her head and hat take up most of the visible interior space. Catrina means female dandy, and the driver of the carriage resembles Posada’s Catrín (Catrina’s male dandy counterpart). One can say, then, that Posada’s Catrín and Catrina (the former subservient to the latter) figuratively rode the carriage of death (through Day of the Dead) to immortality. And Posada, of course, went along for the ride. He achieved long-lasting eminence and admiration far beyond the dreams of most of the great luminaries and celebrities of his day.

Brandon Maldonado, “The Carriage” (detail of horse and Catrín/coachman), 2010, oil on panel.

At the same time, Maldonado’s painting is strange and disquieting, like a dream that is vivid and detailed, but also quite impossible. The carriage doesn’t seem like it will ever move. Though it casts a shadow, it resembles a stage prop. It only has two wheels. And the toy-sized horse is but a ghost. This phantom steed is semi-transparent.

Its transparency has no deliberate symbolism. “I just made it up,” says Maldonado.

The Carriage is done in the style of an ex-voto painting. Such paintings were a form of thanks. When devotees of popular Catholicism felt danger, they prayed and vowed to commission a painting if they received supernatural assistance or deliverance. The inscription on the bottom of Maldonado’s painting mimics the inscriptions on ex-voto paintings.

Ex-votos were primarily painted by untrained artists. They often featured highly original and fantastical effects. That is why they were prized by Mexican modernists and the Surrealists, among other modern artists. Maldonado’s technique, which is far more skillful than the vast majority of ex-voto painters, is more like the work of a trained artist.

The Carriage, unlike an ex-voto, does not feature an image of deliverance by a saint or some other protective or miracle-working holy personage. But perhaps we can say that it is like an imaginary ex-voto, one wherein Posada is delivered from the obscurity of his humble station in life and from the invisibility of the pauper’s mass grave in which he was ultimately interred.

Today Posada is famous — even to people who have little interest in or knowledge of art. He’s even much more than an artist — Posada is a national hero and a cultural icon. And, unlike the great and famous ancient Greek sculptors — whose every bronze masterpiece has been melted down for the value of its dross ore — a great quantity of Posada’s creations have outlived him. Moreover, the images he created proliferate (by other hands) to a degree that is almost unimaginable.

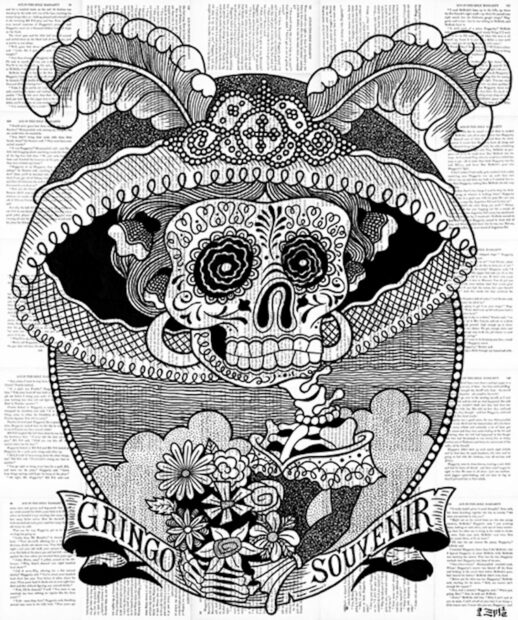

Brandon Maldonado, “Gringo Souvenir,” 2012, ink on vintage pages of text, on canvas, 40 x 30 inches.

Maldonado provided this explanation of the inspiration behind his Gringo Souvenir:

The Catrina is the ultimate gringo souvenir, simply because it’s the image you see marketed most on t-shirts, postcards and whatever else one can imagine they could put her face. You go into a shop with Mexican folk art and you can almost guarantee you will be able to walk out with multiple Catrinas, in some form or another. Diego Rivera loved her so much he even depicted himself holding hands with her.

I was curious why this skeleton had so much torsion in her body (she is bent sharply at the neck) and why the image was made on top of pages of texts.

Maldonado explained that he was simply seeking variety. After seeing and making so many straight-necked Catrinas, he wanted to do one that was really bent out of shape.

In order to balance the big skull and hat, Maldonado twisted Catrina’s body forward. Her bouquet of flowers, which Catrina grasps with her skeletal hands at the bottom of the image, also served to offset her hat and skull. The latter, which is decorated like a mask, also has the appearance of a relatively flat mask. Despite the flowers and the floral decorations around her eyes, this Catrina looks rather glum, with gritted rather than smiling teeth. Perhaps she does not wish to be carted off as a gringo souvenir!

Maldonado utilized the pages of text simply because he had them at hand. He liked to draw on pages from old books. He purchased vintage books specifically for that purpose, using the blank pages that were opposite plates. These pages had pleasing textures, wrinkles, discolorations, foxing, ink transfers from plates, and other effects of aging. In this instance, Maldonado took some pages with text — which he had previously regarded as useless — and he glued them onto a stretched canvas. He proceeded to draw his glum Catrina over the texts.

The Gringo Souvenir image caused quite a stir in Taos when it was used in a sweepstakes promotion in 2013, as reported by the Taos News (J. R. Logan, “‘Gringo’ contest draws complaints about racial sensitivity in Taos,” June 6, 2013). Local Anglos, including Steven Gootgeld, took offense at the term gringo. Gootgeld complained: “In this community, where some Hispanics still hold a grudge for the invasion of the Anglos — and I am one — I consider it a sensitive issue.”

The Taos News also cited Enrique Lamadrid, chair of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who said the term gringo was common in Spanish-speaking countries and that it meant someone who was from somewhere else. He traces its origins to centuries past, when many Greeks came to Spain, and the word for Greek (griego) became synonymous with foreigner.

Maldonado didn’t use gringo in a pejorative manner. As he noted to me:

When Mexicans refer to me as a gringo, I’m not offended. But it took me a while to realize that everyone from the U.S., whether they are Nuevo Mexicanos, Chicanos, or whatever, are “gringos” to them.

Maldonado also notes that Anglos in Taos are particularly sensitive to the term, which they often view as a sign of hostility. Maldonado has frequently seen graffiti in Taos that says “Go home, Gringos!” or “Go home, Texans!”

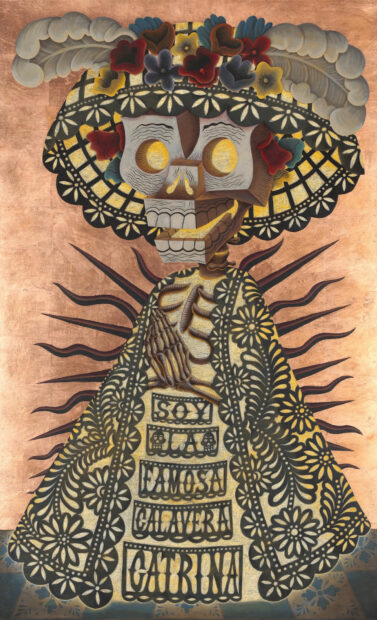

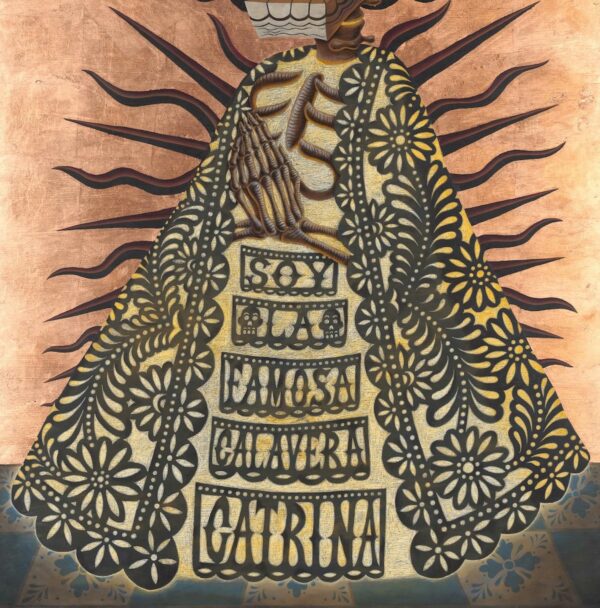

Brandon Maldonado, “La Calavera Catrina,” 2018, oil and gold leaf on panel, 60 x 36 inches, private collection.

Maldonado calls La Calavera Catrina “a tribute to Posada’s Catrina.” It is also a grand synthesis of Spanish Colonial and Mexican sources.

Brandon Maldonado, “La Calavera Catrina” (detail of skull and hat), 2018, oil and gold leaf on panel, 60 x 36 inches, private collection.

Maldonado utilizes Catrina’s signature hat, which is bedecked with paper flowers and ostrich feathers. For her skull, however, Maldonado utilizes his own signature Cubist-influenced style that he developed around 2011. The conical shape of the figure’s body references traditional New Mexican religious statues, which were carved out of wood and often have rather geometric bodies.

Brandon Maldonado, “La Calavera Catrina” (detail of body), 2018, oil and gold leaf on panel, 60 x 36 inches, private collection.

The black and off-white patterns of this figure’s hat and gown mimic the look of paper picado. The latter is cut tissue paper —often brightly colored — that is utilized during Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico and elsewhere.

But Maldonado goes a step further in this work, which is fully three-dimensional. His artistic fiction is that he is depicting a sculptural luminaria (a pierced metal candle holder). Such objects are commonly made out of tin, and have holes punched into them.

Maldonado wanted to create the effect of internal light emanating from one or more flickering candles. He began this canvas by painting a solid black ground. The black shapes that look like papel picado are actually what remains of this black ground. To create the golden glow, he covered portions of the black ground with off-white conté crayon, which created a waxy effect. He subsequently over-painted the conté crayon layer with uneven amounts of yellow paint to transmit the sense of variable light.

So the “figure” — the black forms that constitute this apparent luminaria — are actually formed by the “ground” (the remnants of the layer of black paint with which the artist began this picture).

And what seems to be vacated space (seemingly the empty, golden-lit interior of a hollow sculptural form) has been created by multiple layers of pigment.

Actual luminarias are fashioned from solid sheets of metal that are pierced, punched and bent. They have a more solid overall form than Maldonado’s Catrina. He has created an evocation of a luminaria in the form of a Catrina, whose black outlines mimic papel-picado.

Maldonado has not connected all of the parts of this image. Some of them seem to be floating in space. Nonetheless, he says it is “a dream of mine to realize this image as life-size, three-dimensional sculpture.”

Maldonado surrounded the black figure with gold leaf to enhance and amplify the sense of flickering light.

The blue tile floor on which the image rests recalls the Talavera tiles made in the colonial city of Puebla, where Maldonado has spent a considerable amount of time.

Finally, the rays behind Maldonado’s figure almost seem like they could be connected to her skeletal system. But they are instead a reference to the Virgin of Guadalupe, and the rays of light (known as a mandorla) that emanate from her. The praying pose of her skeletal hands also serves as a reference to Guadalupe.

Maldonado has seen several large bronze versions of the Virgin of Guadalupe, both in Mexico and the U.S., and they influenced his treatment of the mandorla. If one looks closely at these individual flames, they are part brown and part black — like two conjoined stripes. The black areas are remnants of the black ground.

The text Maldonado has written on this image translates as “I am the famous skeleton La Catrina.” Maldonado calls Posada “the king of skeletons.” He emphasizes that the artist is “a great pride to his hometown of Aguascalientes,” who have found many ways to commemorate his work.

For one example, see the homage to Catrina made in Aguascalientes in 2013, illustrated multiple times in Catrina, Part 3. It consisted of 5,700 people (including the governor of the state of Aguascalientes) in black or white t-shirts that formed a human Catrina mosaic. Maldonado witnessed this extravaganza in person.

Maldonado’s La Calavera Catrina is a grand work of cultural and artistic syncretism. This synthesis of Mexican arts and culture is Maldonado’s way of saying that Catrina — though she is a secular figure with no religious role or significance — has achieved something akin to secular sanctity through her deep identity with Mexican religious traditions. During Day of the Dead — whether in Mexico or anywhere else in the world — Catrina often appears to function like a presiding deity. It’s almost as if she were the saint of Day of the Dead, though no supernatural powers are attributed to her.

Maldonado, in fact, gave me a statement to this effect: “She is the patron saint of Dia de los Muertos imagery. So I have incorporated her, time and again, as such, in much the same way a Santero [saint-maker] would treat the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

Brandon Maldonado, “The Portrait of Doña Catrina,” 2019, oil on panel, 64 x 48 inches.

The first thing that grabbed me about The Portrait of Doña Catrina was the way her umbrella almost seemed to serve as her hat. I’ve sometimes compared Catrina’s big hat to an umbrella. See the beach umbrella-sized hat in Catrina, Part 3, which was modeled by Callisto Griffeth for the Mexic-Arte Museum’s Catrina Ball benefit in 2015.

I asked Maldonado why he gave this Catrina such a small hat. He replied: “a big hat would have been like a double umbrella — and she already has a big umbrella. Enough is enough!” He also cited his taste for variety. Maldonado doesn’t want to do virtually identical forms over and over again. “So I gave her a different Victorian fashion look than the one Posada gave to his Catrina,” he explained.

The second thing that really got my attention was the way this figure was pointing at the ground. This gesture, along with the river that was depicted in the background, led me to believe it was a reference to Francisco Goya’s Duchess of Alba of 1797.

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828), “The Duchess of Alba,” 1797, oil on canvas, 210.2 x 149.2 cm, Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Maldonado confirmed that Portrait of Doña Catrina was inspired by the Goya: “It was actually done during a period that painting toured as part of a group show to the Albuquerque Museum. It had such as a presence in the room that it made me want to do a life-size standing portrait.”

The exhibition Visions of the Hispanic World: Treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library was in Albuquerque from November of 2018 through March of 2019. I discuss the Hispanic Society, its new director, the touring exhibition, and the Goya in a 2021 Glasstire article.

The oversized head and the large eyes in The Portrait of Doña Catrina come from Maldonado’s background in graffiti and his interest in Japanese anime, as well as influences from Disney characters. The kind of head he gave her (with white face paint overlaid with colored patterns and a blackened nose) is sometimes referred to as a Sugar Skull-style head.

As for the figure’s pointing gesture, Maldonado has this to say: “I don’t know why she appears to be pointing downward. Someone asked me that as I was working on it, and I was like, wait, what? I thought the finger was just dangling.”

Because he is color blind, Maldonado knew that if he altered the position of the white finger, he would not be able to match the reds on the figure’s garment. “It was too late to change it,” he said, “so I figured it can be a mystery for all of us to ponder, myself included.”

In the Goya painting, the Duchess points to an inscription in the dirt that reads “Solo Goya.” Ironically and mysteriously, the word “Solo” — whose precise meaning in this context is much debated — was evidently painted over. It “reemerged” when the painting was cleaned in 1959. (See footnote 38 in Priscilla E. Muller’s “Discerning Goya,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal, vol. 31, 1996, available as a PDF online).

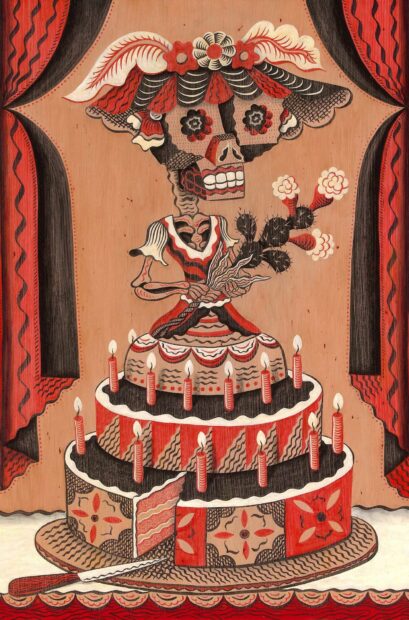

Brandon Maldonado, “Cake Lady” (20 years of Muertos anniversary piece), 2021, oil on wood, 23 x 25 inches.

As a final example of Maldonado’s menagerie of Catrinas, I present Cake Lady. She is a Catrina figure (note the hat and feathers) that grows out of a cake. The drapery and the painting style recall traditional New Mexican religious paintings, though the skull is rendered in Maldonado’s Cubist-influenced style.

Cake Lady is holding a flowering nopal cactus that is sheathed in leaves. Maldonado describes these as “just some leafy stuff to emphasize it being a bouquet.” Maldonado utilizes bouquets as substitutes for religious objects that Catholic holy figures generally hold in New Mexican religious pictures. He thinks it is fitting for a woman to hold a bouquet, but, essentially, it is “just a substitute prop.”

I asked why he gave Cake Lady such a prickly bouquet, and he replied that he was just imagining what might have been available in colonial times, in present-day New Mexico or Southern Colorado. A typical modern bouquet would have been out of the question.

The cake is celebratory: it refers to the twenty years that Maldonado has been making images for Day of the Dead. Its layers are comprised of various devices used by santeros in popular religious art.

Maldonado has taken a very individual path to become an artist. Initially, he feared that his colorblindness was a barrier he might not be able to overcome. He was subsequently derailed when he tried to study at an art school. His artistic vocation developed out of boredom in Spanish class, and also from his fascination with the Day of the Dead. But the main engines that always drive Maldonado are his desire to create, and his equally strong desire to share his creations with a wide public.

Brandon Maldonado, “Cake Lady” (20 years of Muertos anniversary piece; detail of cake), 2021, oil on wood, 23 x 25 inches.

From my perspective, Maldonado is having his cake, and eating it too.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator who has organized more than thirty exhibitions. He holds a B.A. from Brown University (Semiotics) and a Ph.D. from U.C. Berkeley (History of Art).

1 comment

At Foto Relevance, Geoff Winningham had a book signing event for his just published book

“ A Trail of Marvels”. It documents in wonderful photographs the many visits to Mexico to document and share in the festivities that are held all over Mexico on an almost daily basis. The excellent written description brings you into the depicted scene. It is a magical book.