Catrina has long been the face of Day of the Dead. Increasingly, as a striking and unforgettable visual ambassador of Mexico’s unique cultural heritage, she is rapidly becoming one of the most recognizable visual symbols of Mexico itself. This is the fifth article in an annual series dedicated to all things related to Catrina. It focuses on Catrinas that were made or manifested in 2022 in Mexico and the U.S.

Catrina was given life by the printmaker José Guadalupe Posada, in the form of a grinning skull with bare shoulders wearing a preposterously large, luxurious hat. Its first known publication was in a broadside (a large newsprint sheet with a satiric text) that appeared after the artist’s death in 1913. Posada’s Catrina image was elaborated by Diego Rivera into a full figure in a large fresco painted in Mexico City in 1946-47. The word catrina, which means female dandy, did not become attached to Posada’s image until many years after his death. Posada’s print lampooned the aping of European fashions in Mexico. Rivera rehabilitated Posada’s satiric image by endowing his Catrina with indigenous attributes. In Rivera’s hands, she became a nationalist symbol instead of a European-imitating object of ridicule. The vast majority of subsequent Catrina images, however, follow Posada rather than Rivera by presenting Catrina as a female dandy rather than a personage with indigenous symbols.

For a discussion of the origins, transformations, and symbolism of the Catrina image, click here for Part 1 from 2019, “José Guadalupe Posada and Diego Rivera Fashion Catrina: From Sellout to National Icon (and Back Again?).” The article also examines various roles Catrina has played in Mexican and Chicano art and culture, beginning with Posada’s broadsides. Part 2, “Catrina Mania!,” and Part 3, “Catrina Mania III,” are further explorations of Catrina-related phenomena in art and popular culture. Part 4, “Catrina Mania IV: Brandon Maldonado’s Catrinas,” treats several of the Catrinas made by the Albuquerque-based artist.

A Big Catrina by the Sea in Puerto Vallarta

Detail of Catrina (with palm leaf-like feathers) towering over palm trees, full height 24.67 meters, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico, 2022. Photograph: Garza Blanca Resort Blog.

Local artist Alondra Muro Carrillo, with a team that included various professionals and art students from the University Center of the Coast, oversaw the fabrication of a 74-foot- (22.67-meter) tall Catrina in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Resting on a metal and fiberglass frame just a few feet from the ocean, the monumental Catrina’s blue gown and painted iconographic details reference the sea.

As noted by Guinness, “The statue’s fingernails, which are the size of an adult’s forearm, were hand-painted and decorated with images of fish, shells, and manta rays.” Her dress also has oceanic imagery, confirming her status as a coastal Catrina.

Catrina on the boardwalk, Puerto Vallarta, 2022. Smaller Catrina figures are visible behind the vintage cars in the lower right. Photograph: Garza Blanca Resort Blog.

A year of planning, as well as labor by architects, designers, carpenters, seamstresses, painters, and other workers resulted in a statue that was certified as a Guinness World Record on November 2, 2022. The statue’s massive size and particularized craftsmanship reflect the civic ambition, competition, and one-upmanship that has been a part of Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico and elsewhere (especially the U.S.) in recent years, as noted in the Catrina articles linked above. It is a bit jarring to see the Catrina on a tourist resort beach, since most monumental Catrinas I have illustrated in previous articles have been in close proximity to colonial churches.

The Puerto Vallarta Catrina was measured with the help of a drone, which calculated the highest elevation of Catrina’s hat. The measuring process was overseen by Alfredo Arista Rueda of Guinness World Records. It was officially witnessed by two experts: the president of the College of Civil Engineers of the Coast of Jalisco, José Arce Aréchiga, and engineer César Bernal Santana.

Puerto Vallarta was the only city to register a Catrina for consideration by Guinness in 2022. The competition has a number of criteria, including proportionality to conventional, smaller-scale Catrina statues. (Otherwise one could make a tower with a small head and call it a record Catrina.) Designs must be pre-approved before they are eligible for consideration by Guinness.

Reportedly, a larger Catrina statue was made in Veracruz in 2022, but because it did not go through the registration and pre-approval processes, that statue was not eligible for the Guinness record. See Mexico Daily Post.

I report on a variety of Catrina-related phenomena, regardless of whether these objects or activities are sanctioned by Guinness or other bodies, so I discuss and illustrate the monumental Catrina made in 2022 in Misantla, Veracruz below.

Workers with Catrina’s head on the ground, Puerto Vallarta, 2022. Photograph: Out & About in Puerto Vallarta.

The construction of the Puerto Vallarta Catrina was unusually well documented in photography, providing an opportunity to see how it was assembled.

Details of the statue, photographed alongside workers, help one to comprehend the statue’s monumental scale. In the above photograph, a student artist is painting decorations around the skull’s eye sockets, which are large enough for a person to crawl through.

Workers help guide Catrina’s skull, which is hoisted by a crane. The bottom of the skull has a large void that is being fitted onto a horizontal steel beam that will be its primary means of support.

Workers on platform with Catrina, Puerto Vallarta, 2022. Photograph: Out & About in Puerto Vallarta.

Now that Catrina’s skull and neck are firmly affixed, workers, seen here on a platform, can begin to dress her.

Detail of upper section of Catrina, Puerto Vallarta, 2022. Photograph: Out & About in Puerto Vallarta.

As one can see from the above detail, the upper section of Catrina’s dress is painted with oceanic imagery.

Though the Garza Blanca blog claims that Puerto Vallarta “is one of Mexico’s most passionate places about the Day of the Dead,” traditions are strongest in rural areas with high concentrations of indigenous populations. These are far from tourist resorts on Mexico’s seashore.

That is not because Day of the Dead is primarily indigenous. Between the Spanish conquest and centuries of Catholic domination, indigenous religious traditions were very effectively eradicated, leaving us with very little information about pre-Hispanic beliefs and practices. Instead, archaic Catholic traditions that originated in Europe were better preserved in these traditional rural areas, and they have often been mistaken for or misrepresented as indigenous religious traditions. These rural areas are less affluent, generally remote from (or on the far fringes of) modern urban centers, and they are relatively untouched by modernization. See my 2019 Glasstire article “Is Day of the Dead More Indigenous or Catholic? Friars Durán and Sahagún vs. Wikipedia.” I also treated this material in shorter form in “A Brief History of Day of the Dead” in the San Antonio Report in 2020.

Nowadays, of course, everyone in Mexico (especially foreign visitors), wants to get in on Day of the Dead, whether for solemn participation and commemoration, or for fun and/or profit. Nothing garners publicity (and tourist dollars) quite like an officially sanctioned world record.

In addition to the giant Catrina and some smaller Catrinas, the mile-long Malecon boardwalk in Puerto Vallarta featured several Day of the Dead offerings and installations. For photographs of some of the smaller works, see the Garza Blanca Resort blog.

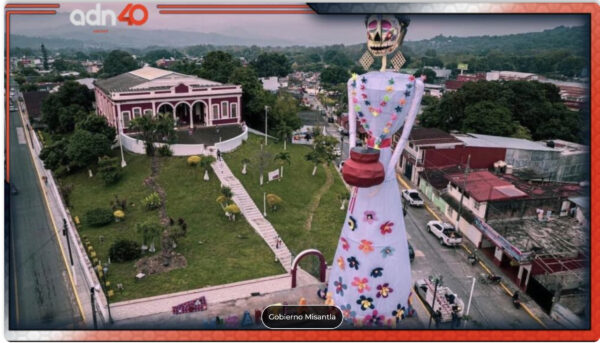

An Even Bigger Catrina in Misantla, Veracruz

On October 31, 2022, the Diario de Xalapa declared that when Puerto Vallarta announced the completion of its Guinness record-seeking Catrina, the Veracruz municipality of Misantla “already had installed a much taller one, at 29 meters!”

The paper further notes that an annual monumental Catrina has been featured in Misantla as a “special guest” and a tourist attraction since 2018. All of these Catrinas have been the handiwork of artist Martín Rodríguez.

Catrina in Misanteca costume (detail of upper section), Misantla, 2022. Photograph: David Ordaz, Twitter.

In 2022, Rodríguez outfitted his Catrina in the traditional Misanteca costume, which consists of a white dress bedecked with flowers, colorful star-shaped necklaces, a red sash, a clay pot, earrings, and a colorfully painted, mask-like face.

The monumental Catrinas have had a significant cultural effect in Misanteca. The Diario Xalapa reports that, according to the journalist Ángel Miguel Cuevas,

the catrina is coming to be regarded by residents with pride and as an identity symbol, similar to the altars they create to honor the dead.… on the other hand, there is a slight reduction in the number of people interested in making indigenous-style altars for the departed.

Despite everything, he celebrates the fact that the custom [of altars] is maintained in this town in the central mountainous region of Veracruz, which has Totonac roots.

In a video discussing the monumental Catrina he made in Misantla in 2021 (which could be his finest one), Martín explained that it was not recognized as the world’s largest because Guinness charges a (presumably prohibitive) fee to adjudicate its official world records. Even if his Catrinas had been officially entered into the Guinness competition, it is possible that Guinness might have rejected his designs as too schematic (especially the arms and hands).

The city of Xalapa, Veracruz also had a large Catrina procession in 2022. A video of it is linked here.

A Catrina on Magnificent Mile, Chicago

José Luis Martínez Pasillas, Catrina statue (with a young woman dressed as Catrina), 10 feet high, installed in Chicago, 2022. Photograph: Colores Mexicanos Chicago Instagram.

José Luis Martínez Pasillas created a striking Catrina decked out in a slinky red dress in Aguascalientes, which is Posada’s home town. It was shipped more than 2,000 miles for a prime location on Michigan Avenue, in a section called Magnificent Mile, in front of Colores Mexicanos, a gift shop owned by Gabriel Neely-Streit and Erika Espinosa. Expenses were paid by the Mexican Consulate and private donors.

As Espinosa told CBS News Chicago: “It’s a representation of our culture and of all the Mexican people here in the city.” Noting that the Mexican population of Chicago exceeds 1 million, she added, “In this season, it’s very important, because it’s when we remember our beloved ones who passed — and everybody can celebrate.”

The Colores Mexicanos Instagram post, however, mistakenly claims that “Catrina is a beautiful representation of all the deceased who come back to celebrate with us in these times.” Catrina is a creation of urban, secular traditions. She doesn’t represent the departed, nor does she have any religious function.

As mentioned above, Posada created her as a satiric image, as someone to be mocked. In Part 1, I noted the harsh ridicule in the text that accompanied the first posthumous printing of the broadside that featured Posada’s Catrina image (Posada did not write texts for his images). While Rivera presented Catrina as Posada’s creation in the fresco discussed in Part 1, he also transformed Catrina by endowed her with indigenous attributes.

The Catrina statue on Magnificent Mile imitates smaller ceramic statues (like those that inspired the Puerto Vallarta Catrina). However much one might regard this image with affection, this Catrina is a conventional representation of a female dandy, a haughty and vain object of satire, as are the male dandies, known as catríns. This statue is meant to be humorous. It is not a solemn representation (nor a symbol) of an ancestor returning from the underworld. If one intended to endow Catrina with new significance, she would have to be physically transformed in a dramatic fashion. For an example of a dramatic transformation — one that has both religious and political significance — see the Catrina figure by Maldonado that is discussed at the end of this article.

A Bakers’ Delight

Catrina Bread Mosaic, Municipio de Zacatlán, Puebla, Mexico, 2022. Photograph: Guinness Book of World Records Facebook.

The tallest Catrina wasn’t the only Day of the Dead-related Guinness-sanctioned record that was shattered last year. The record for the biggest bread mosaic was also broken. According to UPI, five bakers in Municipio de Zacatlán in the state of Puebla worked for two weeks to bake the 20,689 shell-shaped loaves known as conchas that formed the mosaic. That’s a lot of kneading and baking, and it no doubt took a lot of dough. The mosaic covered a total of 2,222 square feet.

While this was a very impressive feat on the part of the bakers, the artistic program for the mosaic was somewhat disappointing. The Catrina in question lacks the big hat found in the tradition established by Posada and Rivera. Moreover, since the word catrina means female dandy, I question whether this figure warrants that term.

This skeleton is neither dressed nor adorned in an ostentatious or pretentious manner. She is no doubt wearing her best clothes, but all villagers wear their best outfits during festive occasions. Does that make them dandies? I don’t think so.

Additionally, there is a lot of dead space in this design. It could have been enlivened with geometric patterns, or a linear rendering of architecture, or a landscape.

Overall, this bread mosaic is not very aesthetically impressive. The skeletal woman lacks a requisite Catrina hat, which, as I argued in Part 1, is sufficient to confer Catrina-hood: “The hat alone is enough to crown a Catrina. After all, it sufficed for Posada.”

Nonetheless, I felt this mosaic should be included in this article because it is a record breaker.

A Colorful Veggie Catrina in Huamantla, Tlaxcala

Of all the Catrina mosaics made in 2022, perhaps the veggie Catrina made in Huamantla in the state of Tlaxcala was the most beautiful. Closely following Posada’s print, it was fashioned entirely out of foodstuffs found in the Mexican kitchen. Thirty other decorative works were made for Day of the Dead in Huamantla in 2022. For a video, see Milenio.

Veggie Catrina (detail of head, hat, and upper torso), Huamantla, Tlaxcala, 2022. Photograph: Línea Directa.

Catrina’s skull and bones were made with white onions. Dried chiles formed the black eye sockets and the other textured areas of the mosaic that are black. Various types of potatoes served to make the reddish-brown fields of color on the hat and in the areas immediately beneath it. Mandarin oranges were also utilized to render marigold flowers in the hat.

Nopal cacti provided the green colors for the diamond shape in the lower center, which was accentuated by bright red bell peppers that form its gemlike center. This veggie diamond is surrounded by coloristically diverse stalks of green sugar cane, which are accented by brown streaks. Cane stalks also served as framing devices for the entire work.

The brilliant yellow-orange colors in the lower section and the hat were made with bell peppers and mandarin oranges. When the festivities were concluded, the foodstuffs were given away to the needy.

A Catrina Contest in Fort Worth, Texas

La Catrina Contest (detail of red-hatted Catrina with bejeweled face), Sundance Square, Fort Worth, Texas, 2022. Photograph: I Love Fort Worth.

Sundance Square in Fort Worth held an extraordinary Catrina contest in 2022. Billed as the 1st Annual La Catrina contest, according to 5 NBC DFW, it featured 20 contestants. The event was curated by artist Miguel Martín and Ray Pulido, owners of Colección Mexicana, a Sundance Square shop specializing in artisanal goods from Mexico.

La Catrina Contest (Catrina with Quetzalcoatl headdress), Sundance Square, Fort Worth, 2022. Photograph: I Love Fort Worth.

While Diego Rivera endowed his frescoed Catrina with a feather boa in the form of Quetzalcoatl (among other indigenous emblems), this contestant utilized a feathered serpent headdress in lieu of a traditional Catrina hat. She becomes an embodiment of Quetzalcoatl, as did god impersonators in the time of the Aztecs. Additionally, her semi-circular headdress, with its prominent pointer devices, alludes to one of the greatest Aztec monuments: the Stone of the Sun (a.k.a. the Aztec Calendar Stone).

La Catrina Contest (detail of Catrina with Quetzalcoatl headdress), Sundance Square, Fort Worth, 2022. Photograph: I Love Fort Worth.

As is evident in the detail, it is as if the feathered serpent inhabits the center of the Stone of the Sun. Her face is framed by gigantic ear ornaments, and her red heart is exteriorized on her chest.

La Catrina Contest (detail of Catrina with Rose Gown), Sundance Square, Fort Worth, 2022. Photograph: I Love Fort Worth.

The woman with the rose gown sports an impressive traditional Catrina hat with an elaborate fringe.

La Catrina Contest (detail of Catrina in purple), Sundance Square, Fort Worth, 2022. Photograph: I Love Fort Worth.

I don’t care for the ornaments on this contestant’s dress, but I give her props for the biggest hat!

For more extraordinary photographs from this event, see I Love Fort Worth.

Maldonado’s Catrina Altar at Hollywood Forever Cemetery in L.A.

Untitled (Catrina Altar, Catrina figure made of wood and papier-mâché, roughly 36 x 32 inches), installed at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Los Angeles, California, 2022. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Brandon Maldonado, the artist featured in last year’s Catrina article, made a very unusual Catrina image in 2022 (after my article went to press). Whereas Catrina originated as a wholly secular image with no religious significance, Maldonado utilized “la Catrina symbolically, as a saint of death, so to speak” in his altar installation. She cries and prays. Maldonado also endowed her with a very explicit political message.

The Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles hosts one of the most extravagant Day of the Dead festivals in the U.S. Last year, Maldonado was invited to create a poster for the event. In return, he was given wall space in a cemetery gallery during the Day of the Dead festival.

Untitled (Catrina Altar), detail of Catrina figure with colonial style paintings of grieving angels on either side, installed at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Los Angeles, 2022. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Maldonado’s altar had a dual commemorative function. His Catrina image, fashioned out of wood in three dimensions (with a papier-mâché face), cries tears like a Catholic Virgin of Sorrows. Her hands are clasped in prayer. Below these hands, a horizontal element alludes to crime scene tape.

The stars and stripes that cloak this Catrina refer specifically and emphatically to the U.S. flag. Her pyramidal gown rests on two stepped tiers whose triangular forms refer to Spanish Colonial paintings that are often referred to as New Mexican folk art. For a discussion of Maldonado’s traditional works (which also engage with Cubism), see my 2022 Glasstire article “Crossing Borders: the Work of Ricardo Islas, Brandon Maldonado, and Vicente Telles.”

At the bottom of this pyramidal structure, Maldonado painted faux papel picado banners that memorialize several of the most notorious mass shootings in U.S. schools. They are: Columbine (1999), Virginia Tech (2007), Sandy Hook (2012), Parkland (2018), and Uvalde (2022).

Maldonado provided me with this statement about school shootings, which he takes very personally:

It’s sadly a uniquely American problem we have. I worked in public schools for almost a decade before doing my art full time. Things have just escalated in a terrible way since then. And I feel for my old colleagues that still have to be in this fight every day. As if there wasn’t enough things for a teacher to be thinking about already. I graduated high school in 1999. Months before I walked down to get my diploma, we had the first major shooting at Columbine. And now it’s becoming a monthly occurrence. It’s all just very sad and angering.

Untitled (Catrina Altar), detail of Catrina figure, installed at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Los Angeles, 2022. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Since thousands of people attend the Hollywood Forever festivities, Maldonado “wanted to use [his] platform at this big event to make a statement.” His Catrina figure was utilized to make a social statement about mass shootings at U.S. schools and as a family altar, to remember those who passed on in the last year.

Pictures of Maldonado’s cousins Eric Barraza (1980-2020) and Marlon Crespin (1978-2021), as well as Maldonado’s girlfriend’s grandparents, Frank Romero (1929-2022) and Matilde Romero (1927-2022), are suspended in front of the table. Maldonado also made a painting that was hung above the altar that depicts his grandparents, Modesto Maldonado (1927-2017) and Viola Maldonado (1929-2019).

When I asked whether the idea to create a family altar or a school shooting altar came first, Maldonado replied:

What came first is a chicken or the egg kind of question. I don’t have an answer. These are people in my family and my girlfriend’s family that died. And these kids are dying in schools. So I didn’t compartmentalize it. It was all lives that needed to be honored.

Untitled (Catrina Altar), detail of Catrina’s head, installed at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Los Angeles, 2022. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than thirty exhibitions, including The Day of the Dead in Art in 2019-20 at Centro de Artes in San Antonio, where he also had his last solo photography exhibition, Besos de la Muerte (Kisses of Death) in 2014-15.