“Milk” Exhibition sign for Sean Thomas Johnston at Fl!ght Gallery, San Antonio. Photo: Colette Copeland.

Milk — Contemporary Glass by Sean Thomas Johnston

Fl!ght Gallery

January 5 – January 29, 2023

Best known for his intricately detailed glass marbles, in his current show, Milk at Fl!ght Gallery, Sean Thomas Johnston departs from traditional glass blowing and instead ventures into the conceptual realm of contemporary art. Upon entering the gallery, I immediately thought of Duchamp and his subversive wit. Three walls are lined with faucets leaking white drips. The reference to the readymade, however, ends there. While Johnston sourced the fixtures at Home Depot, the drips are delicate, organic forms of hand-blown white glass. Speaking with the artist, he told me that white glass is particularly difficult to work with, since the translucent milkiness can easily shift to a burnt color when improperly handled. While Johnston was not directly inspired by Duchamp, he was referencing the shift in matter from liquid to solid and creating an optical illusion with his sculptures.

Also on display are glass marbles. These are very labor intensive, and feature meticulously layered organic patterns. Holding them up to the light creates a kaleidoscopic effect, including magical rainbow sparkles, which Johnston says are synthetic opals. The photos don’t do the work justice, so if in town, it definitely needs to be seen in person.

****

Kim Bishop: Threads & Aftershocks

Opening in March 2023 at Sala Diaz

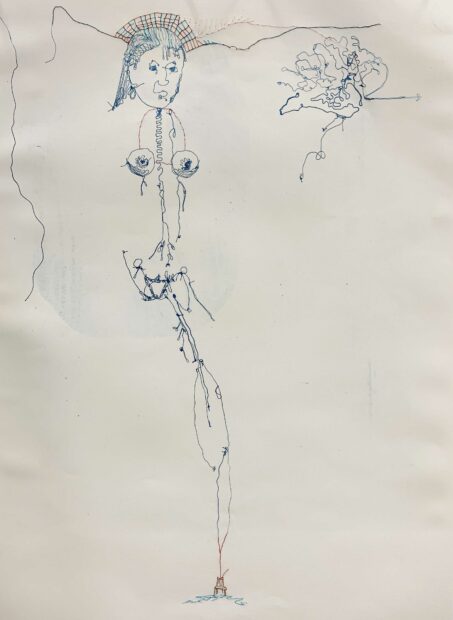

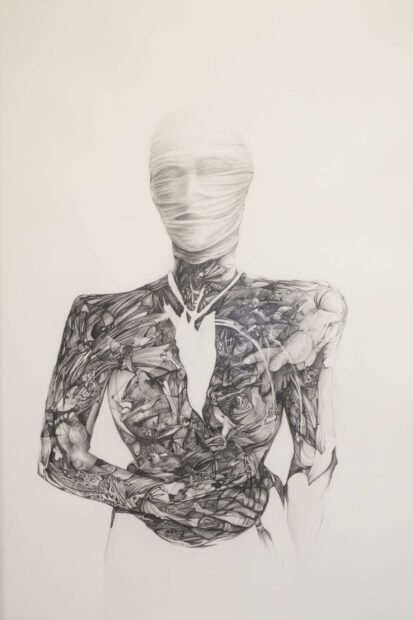

Artist Kim Bishop’s work explores family connections and the ties that bind us individually and collectively over time. Rooted in the body, her pieces pose questions about gender freedom, parental rights, and how history repeats itself. Threads & Aftershocks will feature a new series of thread drawings and large-scale graphite drawings. The exhibition was scheduled to open on January 6, but is postponed until March, due to gallery’s maintenance issues.

In lieu of viewing the show in the gallery, I visited Kim in her home studio to discuss her work. A life-size drawing immediately captured my attention. Inspired by a Carlos Orozco Romero painting, I Carry You features a woman whose face is shrouded by cloth. Her necklace (portrayed by Bishop as a contour outline) is made from a cactus with thorns intact; she holds a bowl to catch her blood spilled by the thorns. Symbolically, the woman is meant to put her vows/sins into the necklace and is then paraded in public to shame her. Think Scarlett Letter. Bishop’s version includes a plethora of surreal, detailed imagery inside the woman’s torso. Conceptually, this work references abortion and the recent abolition of Roe vs. Wade, but it also speaks to nurturing and the life force of maternal love, which prevails despite all odds.

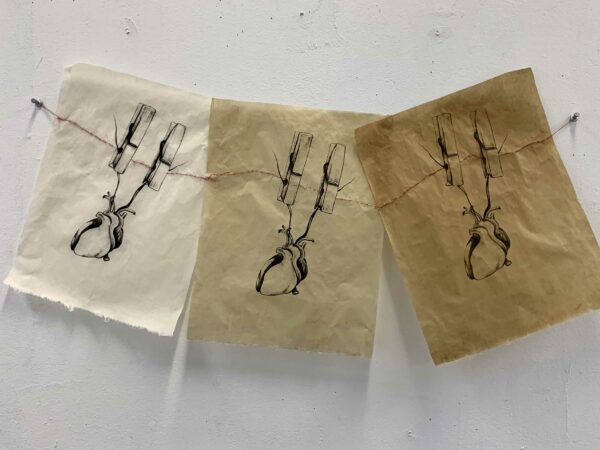

Bishop has also been working on a series of delicate thread drawings made from her grandmother’s sewing kit. To make them, she starts with a contour line drawing and then embroiders on top of the paper. She also employs a printmaking technique in which she burns the thread drawing onto a lithography plate, which she then prints and sews into. This translation of materials functions conceptually as the interweaving of multigenerational families, inherited trauma, and the thread that keeps the binds from unraveling.

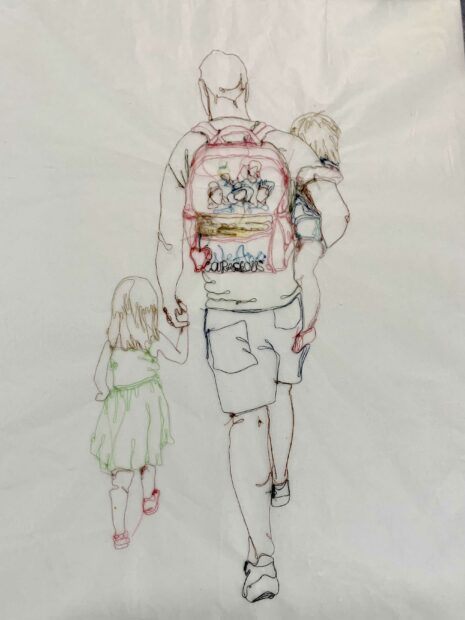

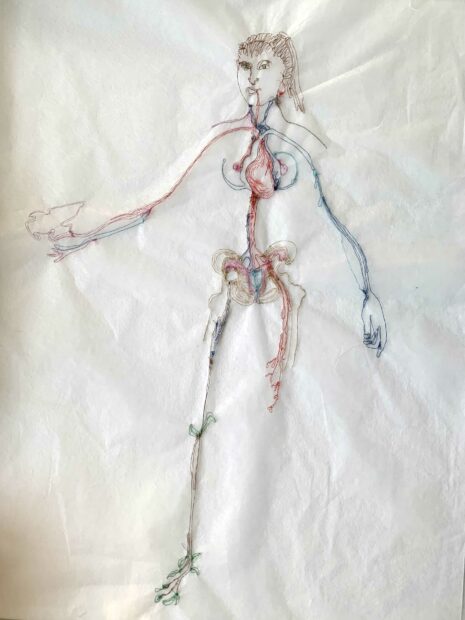

Two drawings that particularly tugged on my heart strings are Mother’s Prayer and Grandmother’s Thread. Mother’s Prayer is a thread contour line drawing of Bishop’s son with his two children. One child is in his arms and one is walking hand in hand with her father. The work represents the struggles of fighting for parental rights, as well as wanting to ensure one’s children have the best life possible. Grandmother’s Thread is a minimalist contour line self-portrait. The red and blue threads represent blood as it travels through the body, first unoxygenated and then oxygenated with life force. This references lifelines — the connectivity of family in our veins.

****

Jesus Treviño: Phantom in the Headlights

Presa House Gallery

January 6 – February 18, 2023

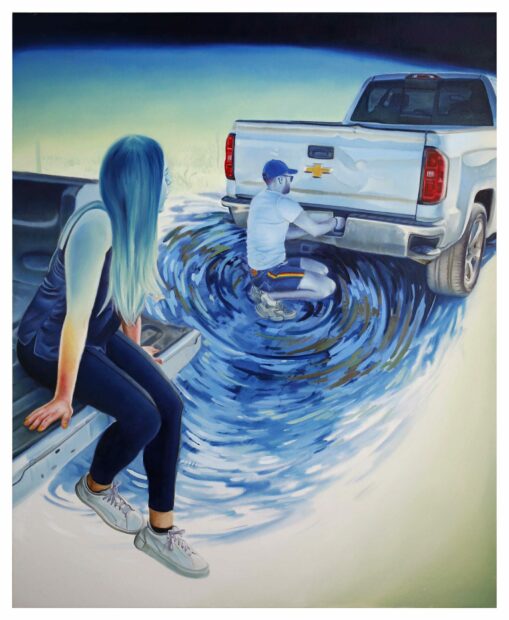

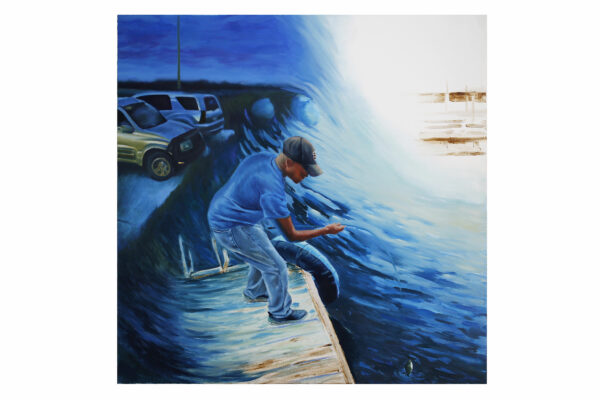

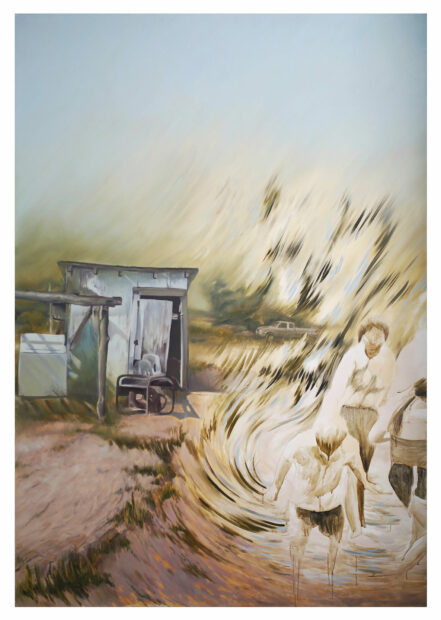

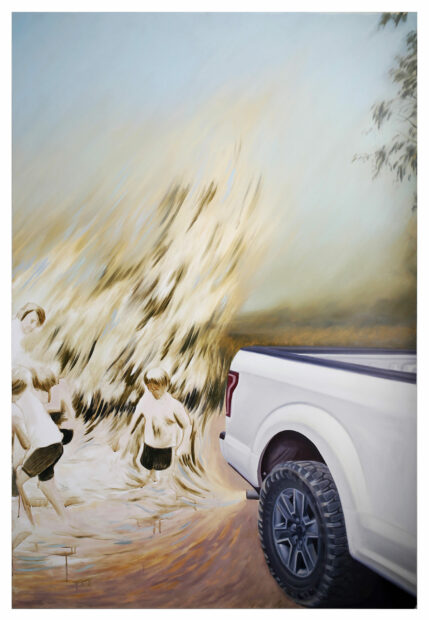

Jesus Treviño’s paintings use family imagery as source material, exploring the artist’s experience growing up on the U.S./Mexico border, as well as themes of displacement and erasure from history. One work in the show, Recuerdos Left in the Dust, is a two-panel oil painting featuring swirling brush strokes that evoke a Texas dust storm with ethereal figures in its center and a white pickup truck on the right third of the canvas. Treviño captures the beauty of the Texas sky, skillfully painting the shifting light and color of an impending storm. While the figures who represent memory fade away, the truck’s hyper realism provides a sharp contrast to the present. Treviño also adds used motor oil from his family’s automotive dealership to the canvas, which prevents the paint from fully drying. As a medium, motor oil is rich with connotations, referencing manual labor as well as the plethora of Texas oil wells and refineries.

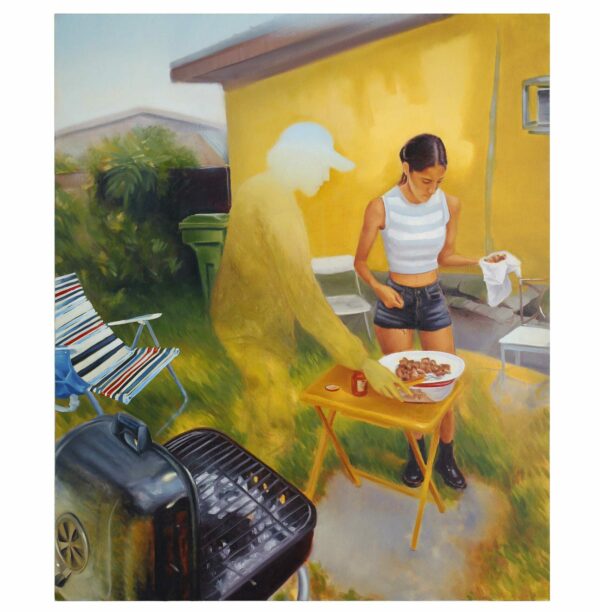

When looking at the entire exhibition, it becomes clear there was a shift in Treviño’s color palette in 2022. The works from earlier utilize warm yellows, such as in Carnesazo, which depicts an outdoor cookout with two figures. A young woman and a chair are painted with vivid detail, but the male figure fades into the sun-saturated background. I interpret this as the recollection of memories of a family member who passed away. The artist describes this work as symbolizing the faith one carries within themselves.

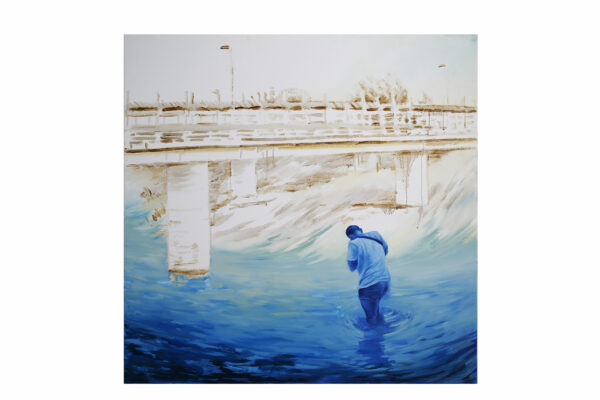

It was difficult to narrow down which paintings to write about, since many are imbued with rich narrative and content. The exhibition’s tour de force is the three-panel work entitled Oil Over Troubled Water. The composition shows the Bridge of the Americas (connecting Ciudad Juarez and El Paso), with the Rio Grande River in the midst of a massive tsunami. Spectators passively watch the storm as waves threaten to destroy the bridge. The third panel shows the calm after the storm, with the bridge still intact. Treviño uses cerulean blue to depict the tumultuous event, yet leaves the bridge colorless, a mere outline lacking detail. The bridge is a spectral presence, symbolizing a hope or dream rather than a memory.

****

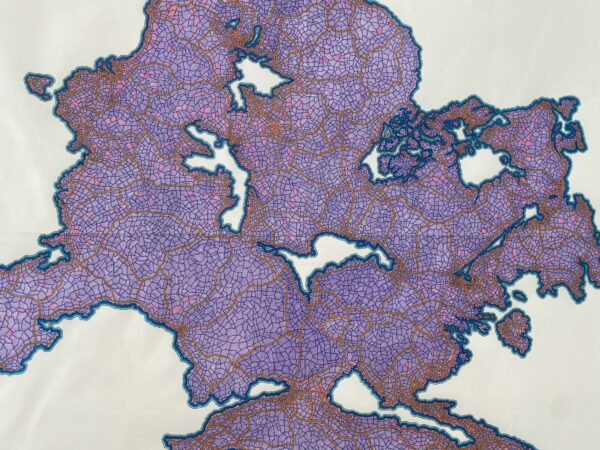

Lordy Rodriguez, “Pangea-1, Detail 10, Richest Countries by Net Worth,” 2022, Ink on Paper. Courtesy of Artpace.

Lordy Rodriguez: Since We Last Met

Artpace

January 12 – April 30, 2023

Lordy Rodriguez, who was the inaugural resident of Artpace’s program in 1995, returns to exhibit selections of his work involving the language of mapping and grids. The map and grid as tools for visual language are ubiquitous in contemporary art making today; what interests me most about Rodriguez’ work is how he deconstructs the map as a visual symbol of power and colonialism. In a video interview, he referred to his work as “deceptive cartography.” As viewers, we look at maps for direction, not only as navigational devices, but to get a sense of the geography of place. Rodriguez purposely provides us with dis/mis information. Thus, his re-imaginings of places and events question governmental and institutional authority

In the exhibition, Rodriguez maps significant political events, such as protests and marches. One might ask: How do we map voters rights, social justice and activist work? In the America Series, the artist reconfigures maps of the U.S. based on his personal experiences, travels, memories, and desires. In his artist talk, he spoke about his role as an artist. As an immigrant, he was encouraged to become a doctor or an engineer, so for him, art is an act of social protest since it goes against the grain of societal expectations.

His current series, Pangea, refers to a hypothetical landmass that existed when all continents were joined about 200-300 million years ago. In Rodriguez’ Pangeas, he reconfigures geography to comment on social, economic, and political issues. Panagea 1 is a map that connects the ten richest countries in the world. The detailed ink on paper drawings show intricate lines denoting roads, visualizing the interconnectivity of global wealth. Contrasting economic wealth is Panagea 2, which maps countries on the “watch list,” according to the International Rescue Center.

Lordy-Rodriguez, “Pangea 2, Detail, IRC Emergency Watchlist,” 2022, ink on Paper. Photo courtesy Artpace.

I would be remiss if I didn’t address the technical aspects of the work — all of the pieces are incredibly detailed and labor intensive. This reminds me of early cartography and the importance of precise handwork in creating maps that are accurate. Perhaps this dedication to obsessive manual labor also serves as an act of resistance.