It feels personally serendipitous that the art collective M12 debuted an installation at Sala Diaz in San Antonio a few weeks ago that explores the elusive seductions and creative freedoms of rural locations. Given that I’ve been on a soapbox against what I believe to be the exploitative essence of gentrified cities, and have been reconsidering the charms of “uncool” places, the mission and identity of M12 is deeply resonant. Based in rural Colorado, M12 is a growing collective of nationwide artists, writers, scholars, musicians, and architects who develop projects that explore the aesthetics of rural cultures and landscapes. The projects include installations and the publications of collaborations between various members on aspects of rural being. In one volume, Cool Pastoral Splendor, stark and beautiful photographs of unpopulated buildings and landscapes by Richard Saxton converse with poetry by Kurt Wagner (of the highly underrated band Lambchop). Another is devoted to the strange intricacies of various equine industries. Through these minimally elegant, black-and-white editions, a tapestry of America’s rural landscape forms — one that is pointedly aesthetic over political, highlighting the haunting ineffable presence of places that is often dismissed as banal, provincial and bigoted.

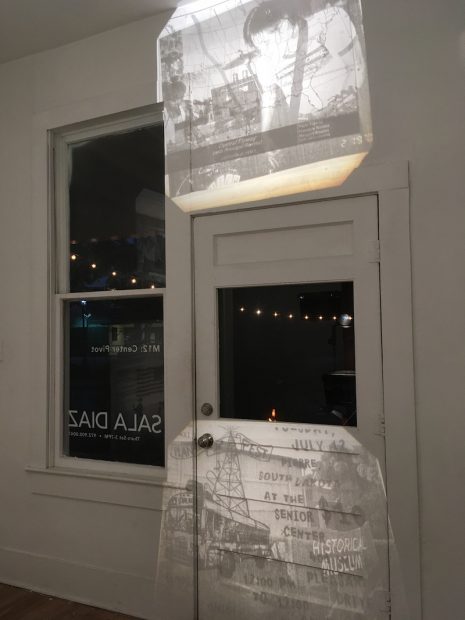

The M12 installation at Sala Diaz is a compilation of sorts. In one room a wooden beam is installed in the center, and delightfully nostalgic overhead projectors are bolted along its sides displaying transparencies of selections from the volumes. In the second room a large expertly cut tree trunk rests on a display and is affixed with horn speakers. Each speaker plays a selection from the accompanying record to the volumes. One record, for example, contains the collective singing Lonesome Prairie in the wilderness; on another, it’s a long list of punk bands.

M12 member Chris Sauter, of San Antonio, describes the approach of the installation as emphasizing “connectivity,” so the pieces extracted from the M12 releases overlap and blur into each other into an initially inscrutable ambience. This has become a current at Sala Diaz: shows that slyly appear either overwhelming or prosaic upon initial viewing because of the density of content, but reveal themselves to be dizzyingly trippy pieces that contain multitudes.

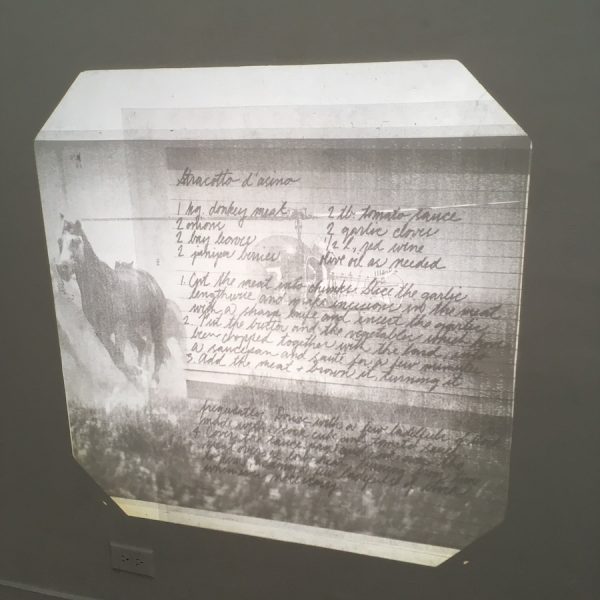

One projection has a recipe for donkey meat (“stracetto d’asino”) adjacent to a UK tabloid headline about a horse-meat controversy. The distance between what constitutes “acceptability” in different factions of society is playfully articulated through the most fundamental of cultural tastes: food. (A side note: When I lived in Beijing, I regularly ate “donkey burgers,” which were kind of like Chinese pastrami sandwiches, from a donkey burger restaurant by my apartment. They were pretty lit.) Another projection overlays a South Dakota punk show flyer over a picture of a small town museum. The symbiosis of the spaces is apparent — in the sparseness of rural living, the vacancy can be a refuge for one’s eccentricities. There are portals everywhere.

One of the show’s most impressive achievements is how well it formally executes the ideas articulated in the volumes. The installation consists of everyday objects — lumber, vintage electronics (like the overhead projectors and loud horns), and a tree trunk — but the result is surreal and deeply rural. One can imagine encountering these works without explanation in a small town and being beguiled by the rightness of their presence.

Center Pivot, the title of this show, encapsulates the dynamics and ethos of it. There is a hideous veil over us, and one must strain the neck to see around it. So look everywhere: to the heavens, but also the empty buildings and fields — the places you drive by when you feel stuck.

At Sala Diaz, San Antonio through February 3rd