Round 53 at Project Row Houses, titled The Curious Case of Critical Race…. Theory?, invited five artists and an artist collective to contribute work that explores the frameworks of Critical Race Theory (CRT). If artists chose not to explore the “frameworks,” then artists could include work about “how the term is leveraged as a catch-all for personal assumptions and/or systems of belief but also respond to the more generalized lived realities that inform the theory.” In conjunction with the artwork, the title/prompt feels like a catch-all.

We all know that Critical Race Study is anything but a theory. It is a timeline of facts. Therefore, I assume that positioning the title in this way is meant to make you do a double-take. But who are we asking to look twice? Everyone? Anyone? Additionally, anything with “The Curious Case …” as an introductory phrase positions the remainder of what follows the sentence as something odd. So, I’m at a loss concerning the title in conjunction with the work. Hence my original conundrum: Is the title/prompt a big ask, a catch-all, or both?

Aside from the title, there are some interesting things happening in each of the Row Houses. Collectively, these artists are grappling with the politics of identity (shout out to Cherise Smith), the thickness of self and living as a person of color (shout out to Dr. Tressie McMillian Cottom), and the celebrations, critiques, histories, and mourning that happens within these lived experiences. A few are also battling with audience and (I’d argue) the white gaze.

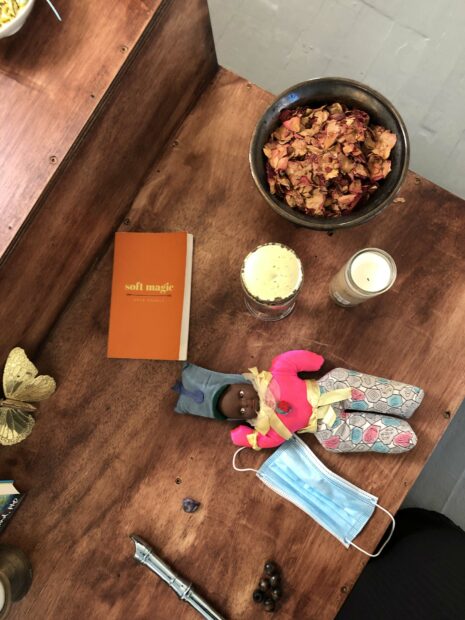

CRT was developed as an academic concept to help understand the structural and racial disparities that endure in our society, engendering differential experiences of law and policy across lines of difference. It has come under attack for a variety of reasons, but most importantly, it forces white and white-passing people to confront their positionality, the ways they have benefited from systemic racism, and the subjugation of the “other.” Of course, many know they have benefited from this system, but they do not want to face themselves in the mirror. We live in a world that historically promotes and romanticizes European immigration, bootstrapping, and conquest, but does not want to publicly acknowledge the histories of theft, enslavement, and murder. And to justify these centuries of subjugation, yes, there were laws, treaties, war, and bullshit science, but there were also objects used to promote (advertise?) this oppression (figurines, masks, etc).

Back to the exhibition at hand, most of the artists in this round go to great lengths to transform their respective houses into their own worlds. Roux, a four-woman artist collective featuring Rabéa Ballin, Ann Johnson, Delita Martin, and Lovie Olivia does this well. In Sensitive About Our Blues, each artist has taken a room of their own in the row house and installed a collection of objects, drawings, paintings, and sculptures. As the only house with walls, it makes sense for each artist to take a space for themselves. However, selfishly, I wish the works were more intertwined and responsive to one another. I yearn for a common thread, an opening, a pattern, color, material, or motif to lead me from space to space.

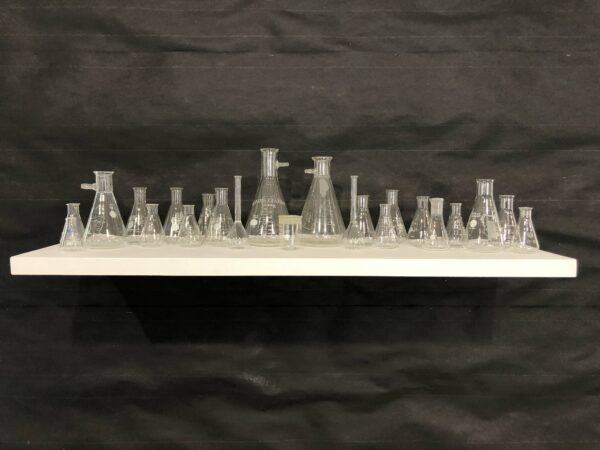

Tammie Rubin explores the weight of objects and motifs in her installation, titled HARMONY COMFORT CONVENIENCE. Rubin transformed the shotgun house’s interior through a combination of asphalt paper and stake flags, with her iconic ceramic sculptures on display. The space is widened by the asphalt wallpaper. Altar-like and quiet, the space forces you to reflect on the various objects such as the wall of red, white, and blue stake flags — how they sometimes mark space for building or repair. And this leads to questions regarding land and who gets to own it, about redlining, migration, and exclusion. Illinois Central 57/59 an installation of lab glass (beakers, flasks, etc.) waits quietly on shelves to be filled, but with what and for what? Varying in height and width at first glance, they reminded me of cockamamie science and racist practices in healthcare. But I am kicked out of this thought pattern once I see, etched on the surfaces, the surprises that calls to Rubin’s familial history. Again, a moment causing viewers to pause and reassess.

Illinois Central 57/59 mirrors Rubin’s ceramic sculptures, titled Always & Forever (forever ever). Rubin transforms a series of conical structures through texture, color, size, and strategically placed holes that read as eyes and vary in shape and size. The ceramic pieces are beautifully decorated (for lack of a better term), with surprises along the surface that are almost playful and animated, yet haunting as they point to KKK hoods and capirote hats. Akin to the stake flags, beakers, and other objects in the space, viewers are invited to read into the formal explorations of the work as well as the historical and/or conceptual threads.

The most successful installations in The Curious Case of Critical Race…. Theory ? not only utilize the row house to showcase the work, but make the house a medium as well. Those that don’t manage to do this feel unfinished — not necessarily unfinished in a bad way, but unfinished in a broad sense. Unfinished because the work is waiting for us (the viewers) to activate it. And the activation seems to be through remembrance, presence, learning, or maybe even yearning: for a not-so-distant past of possibility, or yearning for a different present.

David-Jeremiah’s A Watermelon’s History in Niggas probably perplexed me the most. On one hand, the artist completely transforms the space through minimal means into an immersive display reminiscent of a natural history diorama. And then come the sculptures: black wooden figures, shiny as if tarred, are on the floor among sketches, lesson plans, and a book with the same name as the installation’s title. They have watermelon heads, hands, feet, and ass cheeks. It’s so obvious as to what they resemble that I refuse to write it. And this is where I ask about the audience and the white gaze: Who is the audience? Who is this for? And if I, as a Black-American, straight, able-bodied, cis-woman am a part of the audience, what am I supposed to take away from this? If the answer is “whatever you want,” then this work is a catch-all, employing a variety of racialized symbols for shock. And perhaps that is successful. Because unfortunately, I have no idea how to imagine oppressing a watermelon.

All in all, folks should see the show.

Round 53: The Curious Case of Critical Race…Theory? is on view at Project Row Houses through June 5, 2022.

1 comment

But Ms. Adams, don’t you think we all have to muse on the visceral oppression these tropes impart- their brutality, their mean spiritedness, their absolute disregard of anothers humanity- vis-a-vis the system that created and sustained them over a very long period of time? I mean if anyone is interested in really healing….