I often write and reference the transcendental style in film and other mediums. As defined by Paul Schrader in his book The Transcendental Style in Film: “In 1971, struggling with the concept of transcendental style, I sought to understand how the distancing devices used by these directors could create an alternate film reality — a transcendent one. I wrote that they created disparity, which I defined as an ‘actual or potential disunity between man and his environment,’ ‘a growing crack in the dull surface of everyday reality.'” This growing crack in the dull surface of everyday reality is an apt descriptor for many works of art that use time and patience, but perhaps most clearly seen in film — specifically the global slow cinema movement. These are films made all over the world that employ a somewhat unified filmic language: long takes, wide angles, a static frame, images preferred over dialogue, highly selective composed music, heightened sound effects, visual flatness, and repetition.

I would consider myself basically a wide-eyed zealot fanatic for slow-cinema/transcendental style. I would go so far to say that greatest works of this “genre” (like Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice) are essentially the pinnacles of artistic expression. But for many years there has been a white whale, Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó, his notorious 432-minute magnum opus from 1994. Sátántangó has long been difficult to see given its massive run time (with intermissions it’s about an 8-hour-and-15-minute experience). Facets released a DVD in 2008 that quickly went out of print. The local San Antonio library has a copy, but I never dared a home watch. I felt the temptations of distraction would be too great. I am weak and I would desecrate Tarr’s vision by checking my phone. I needed to wait. I needed to be in the theater.

On the movie’s 25th anniversary, a magnificent 4k restoration arrived and was screened once, very recently, at Austin Film Society, and it will screen at Rice Cinema in Houston on January 18th. I made sure prior to the Austin screening to post on social media jokes about no one wanting to go with me, to secure that I couldn’t bail the day of, like a poser. I woke up, gulped a pot of coffee, drove from San Antonio to Austin, and steeled myself.

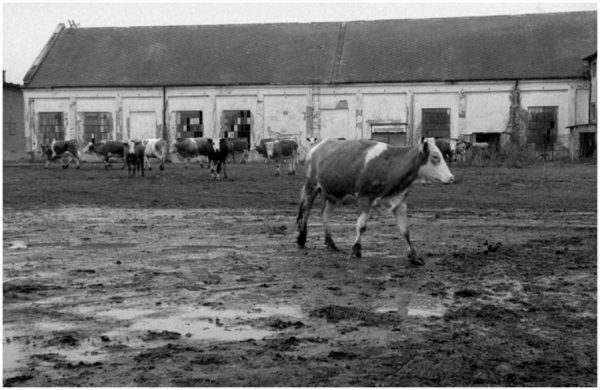

And… it was one of the greatest experiences of my life. Sátántangó, which depicts cosmically miserable peasants in a rainy wasteland in rural Hungary at the end of the Soviet Union, is relentlessly slow (the first shot is a seven-minute take of cows milling around a crumbling village) and mercilessly bleak, yet absolutely beautiful and hypnotic, as well as brutally hilarious. It is unlike anything I’ve ever seen — a quintessential Eastern European fable of conmen and farmers rendered into a meditative metaphysical odyssey that fuses time, landscape, and sound design like a medieval alchemist mixes potions.

Divided into 12 chapters and ingeniously structured like a tango (six steps forward, six back), Sátántangó’s narrative is simple. A destitute communal farm is about to split up the meager funds from the sale of cattle, and a few desperate characters plan on running off with the whole bag, but all is interrupted by the return of a mysterious and powerfully seductive resident long thought dead.

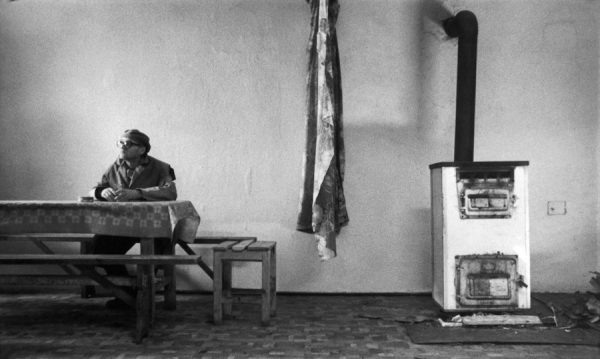

Several of the chapters are so stark and despairing they almost defy belief. In one, an old, fat, drunk doctor staggers out of his filthy abode to refill his brandy jug. Wheezing, he trudges through the relentless rainfall, and often seems dead. This lasts an hour, and is simultaneously horrific, funny, and discomfortingly relatable. In another, a beaten-down little girl poisons her cat and runs around the village with the cat’s limp body under her arm, seeking help to no avail. What is the purpose of depicting such misery, especially in almost real time (sometimes in a surreal, slower than real time)? Tarr is a supreme humanist absent of any moralism; he takes a scenario so grim that its almost almost alien, and allows the viewer to fully enter the world — enter the lives of these downtrodden, as if you were a ghost floating by their side.

Tarkovsky, the master of transcendental style and progenitor of slow cinema, loved water, and in most of his films depicts clear streams and rivulets, rolling tides, radiating pools. Tarr loves water too, but of a murky, muddy nature — blinding rain, oily mirrored puddles, and clouded, silvery basins. The difference is Tarkovsky was a spiritual and religious man, and Tarr is a staunch atheist. But both directors achieve a transference in their work. With them, you go somewhere.

Each chapter revisits incidents from different perspectives, creating a circular eternal recurrence. The setting and the story are a distinct critique of communist Hungary (Tarr adapted the film from a 1985 novel but couldn’t make it until the Soviet Union fell) — how life was drained and frozen, a repeating nightmare of waiting and betrayal. But the film is far beyond this; the landscape takes on a mystically apocalyptic symbolism as if the stage setting of a Beckett play became real and spread across the land like a philosophical pestilence. Tarr is often described as pessimistic, but Sátántangó is far too rapturous and engrossing to be so reductively defined. It is urgently existential, a call and demonstration of taking stock of life and yearning to break the cycle.

There are many unforgettable moments — the walking scenes that have a palpable velocity; the approach shot of a crumbling estate no less monumental than the appearance of the monolith in 2001; a scene in a bar when the churning machinery of all things whirs and time stops. Sátántangó is usually billed as a feat of endurance, “difficult,” “painful,” an exercise in tedium. But from the first minutes of bleating livestock, the rough texture of walls, the billowing curtains translucent like vellum paper, I was in. So much narrative media shuffles around like Spider, the sheepish busboy in Goodfellas, terrified that Tommy (you, the viewer) will shoot him if he doesn’t dance fast enough. What a cruel way to make or take in stories.

Sátántangó demands surrender. You have sought shelter in an endless storm — have some palinka (a fruit brandy guzzled throughout the film), listen to this man’s story. It will take all night. See you in Houston.

Sátántangó screens this Saturday, Jan. 18, at Rice Cinema in Houston, from 2-10 pm.