If you’ve seen Paul Schrader’s brilliant and deeply affecting movie First Reformed, released this year, you were probably struck by its unusual aesthetic choices and ambience. It’s shot in 4:3, so the frame resembles a rectangular window as opposed to a panorama. There’s almost no non-diegetic music (e.g. a score) save from some gurgling drone by Lustmord. There are no quick edits or dolly shots, the frame is unblinking and static like a theater stage except for two rapturous moments. This is all very deliberate. Schrader has crafted a finely wrought homage to a genre of filmmaking he essentially named, articulated, and categorized in his seminal 1972 book, The Transcendental Style in Film, written while he was a grad student at UCLA. In the original book Schrader focuses on three directors: Yasujirō Ozu, Robert Bresson, and Carl Dreyer, who form a latticework for the self-imposed aesthetic limitations intrinsic in the genre. In the new and welcome reissue of the book, Schrader writes a lengthy new introduction expanding the Transcendental Style beyond these three directors, and indeed beyond the genre of film itself, to define a creative perspective that extends across art, film, and music.

Schrader is probably best known for writing the screenplays of the double helix of toxic masculinity ur-text: Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. But he is an underrated director as well. I count nine Schrader films (Blue Collar, Hardcore, American Gigolo, Cat People, Mishima, Light Sleeper, Affliction, Auto Focus, First Reformed) that range from minor to major classics, though many of them have an unsettling and alienating quality.

Schrader has had a fascinating life. Raised in an extremely orthodox Calvinist family (Calvinisim is beautifully and mystically described by George C. Scott in the Schrader movie Hardcore), Schrader did not see a film until he was 17. He has observed that the films you first see and remember inform your aesthetic for the rest of your life. (I favor a “twisted aesthetic,” probably because the first films I saw that made an impression on me were The Exorcist, Blue Velvet, and Apocalypse Now). For Schrader, that meant the difficult, the austere, the quiet impact of such directors he first encountered in film school — Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer, as well as Bergman, Tarkovsky, Resnais, et al.

If you haven’t seen any Ozu, Bresson, or Dreyer films, the concept of the Transcendental Style is probably a bit hazy. Schrader clarifies the definition as a set of specific techniques (compare the Dogme 95 directives, a sort of filthy-squatter version of the Transcendental Style). Transcendental Style includes: wide angles, a static frame, images preferred over dialogue, highly selective composed music, heightened sound effects, visual flatness, and repetition. These techniques are readily apparent in the works of many globally renowned directors, such as Béla Tarr, the Dardenne brothers, Carlos Reygadas, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. It is, in other words, a prime template of serious festival-circuit art cinema.

However, it is Schrader’s poetic ruminations about the Transcendental Style that are more universal, and thus ultimately (and perhaps cosmically) more accurate to the expression and truth of the Style than a litany of techniques. Schrader writes:

“In 1971, struggling with the concept of transcendental style, I sought to understand how the distancing devices used by these directors could create an alternate film reality — a transcendent one. I wrote that they created disparity, which I defined as an ‘actual or potential disunity between man and his environment,’ ‘a growing crack in the dull surface of everyday reality.'”

In the original book, Schrader writes: “Human works, accordingly cannot inform one about the Transcendent; they can only be expressive of the Transcendent.”

My blunt interpretation of all this is that the Transcendental Style essentially induces boredom as deliberate technique in order to produce a sort of “ambient plane,” and then cracks it open with a moment of ecstasy and release. Dreyer’s Ordet and Carlos Reygada’s homage/remake Silent Light are extremely long, probably deliberately boring films about rural religious people, and both have endings one will probably think about every day for years after viewing them. Elaine Radigue’s compositions stretch across entire boxsets and are meant to be played at low volumes, but subtly transform over the hours like the shape of waves under a rising moon. Andy Warhol’s marathon videos such as Empire State Building and Sunset (the latter is currently screening at the McNay in San Antonio) use real time as a device for transcendence — you are doing something you would never do, like watching a building for multiple hours — and the boredom becomes surreal.

Consider Iceland artist Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors, in which nine videos of nine different performers in a crumbling upstate New York mansion sing an aching refrain: “Once again, I fall into my feminine ways.” (A line Kjartansson’s wife said, giving the piece an extra layer of melancholy as it was made in the wake of the couple’s divorce.) This goes on for nearly an hour, the refrain replicating what a chorus to a sad song can be for the heart — a loop bearing grief like clothes on a line in the wind. The Visitors reminds me of a performance of composer Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic I saw on the centennial of said event at the Chapel Performance Space in Seattle. The performers stretched the piece out to nearly two hours, repeating the same simple hymn the Titanic’s small orchestra played as the deck chairs were sliding down the ship, and Bryar’s composition fills the rest of the soundscape with creaks and groans, rolling spools and broken chains. The repetition, the slowness, allowed the room, the air, to play. In the same way, the musique concrete composer Luc Ferrari lets nature play in his works, sampling the pan pipes of French sheepherders. Or the way Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer hold the frame to let the scenery play. The strength of Schrader’s theory is apparent in applicability. It can be used as a heuristic.

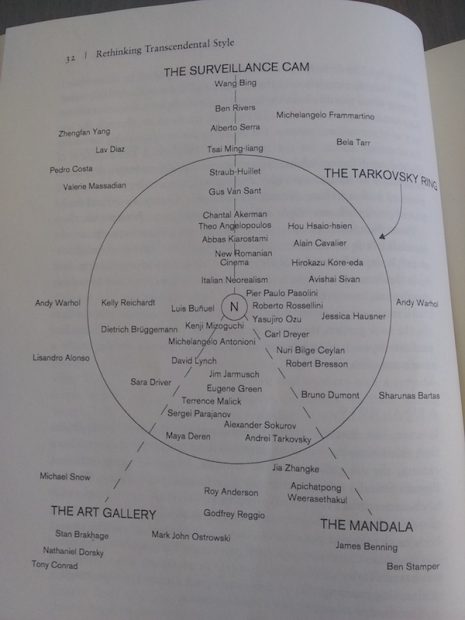

In the book’s new introduction, Schrader uses filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky as a unifying figure to center his theory. This includes a charming diagram dividing the aesthetics of the Transcendental Style into four contemporary categories: Surveillance Cam, The Art Gallery, The Mandala, and “The Tarkovsky Ring,” within which are the purveyors of the Transcendental Style who create “narrative” works. This is a clever move, as Tarkovsky was perhaps the most gifted filmic artist to ever live, whose films evoke moments of transcendence more immediately and unforgettably than perhaps anyone else’s. Schrader quotes from Tarkovsky’s brilliant book of his philosophy of film art Sculpting in Time: “The cinema image is the observation of a phenomenon passing through time. Time becomes the very foundation of cinema… . Time exerts a pressure which runs through the shot… . Just as a quivering reed can tell you about the current or water pressure of a river, in the same way we know the movement of time as it flows through the shot.”

Time is the common denominator of the Transcendental Style and the media that most easily embraces and articulates its aesthetics are logically film, music, and art film/video installations. It’s more difficult for a painting or a sculpture to be in the Transcendental Style, although Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field uses time to turn the poles from chrome to gold to white under the moon. Likewise, it’s more difficult to apply this to literature, although epic poems such as Frank Sanford’s The Battlefield Where The Moon Says I Love You certainly explore and echo the Transcendental Style. Schrader writes that the transcendent cannot be defined, only expressed. But the artists across media expressing the Transcendental Style point together in the same direction, like a divining rod quivering towards unseen water.

The opposite of the Transcendental Style can perhaps be broadly thought of as Extremism. This would extend to everything from the films of Gaspar Noé to the music of Arca. You could, after all, make one epileptic cut and jump from a Ryan Trecartin video to David Lynch’s Inland Empire without a hitch. Extremism expresses a particular existential, fundamental sense of dread — that life is a visceral miasma of sudden horror and agony which renders living essentially psychedelic and occasionally wondrous. I am very fond of Extremism, and find it joltingly cathartic, but I concede it ends the phrase “And then” with a hard period. Usually a sudden burst of shocking violence — say in the glorious new season of Twin Peaks, when an extremely upsetting creature appears in a glass box, bursts out of it, and shreds two terrified lovers to bloody ribbons. The Transcendental Style ends “And then” with an ellipsis… time is the spaces, and the periods are stones skipped on a river.

Given this grotesque age we’re going through, Extremism seems the logical mode to reflect the parade of horribles. But it is important to remember Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer made their most transcendent works after a war that killed 50 million people. The world remained, somehow. Ponder that for a moment.

At a particularly low time in my life I rode my bike through the freezing Beijing winter to the Bauhaus-designed 798 Art District to see Ozu’s Tokyo Story, and wept when Kyoko says, bitterly: “Isn’t life disappointing?” Her sister-in-law Noriko, with beatific empathy replies: “Yes, it is.” I remember seeing James Turrell’s Pleiades at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, where you have to sit for ten minutes to let your eyes adjust to the darkness to detect the low glow. It felt what I imagine being born would be like, or what would happen if when you died your soul somehow continued. The Transcendental Style in its best forms can, like the end of Dreyer’s Ordet, raise one from the dead.

1 comment

This is a nice little meditation. Thanks for this. I’m curious to read the book and see how he qualifies that diagram at the beginning. My knee jerk reaction is to say Michael Snow, Tony Conrad, Stan Brakhage, and Nathaniel Dorsky don’t belong anywhere near an art gallery (unless said gallery has become a cinema) and I don’t know why he used that term, but I think I can see his reasoning.