The uniquely eclectic and experiential annual CineMarfa festival presents a range of historic and contemporary film and video works in such a way that images and ideas organically connect, contrast, and reverberate in the mind over the course of its four days and dozen or so screenings and events. While traditional film festivals often select a high-profile, crowd-pleasing premiere for the opening-night launch, the kick-off program for the sixth annual CineMarfa festival last week was a bold, curated montage that coupled two powerful and very different films that have likely never before been shown together. The two films and their collision set the stage for a coming cinematic journey that would include narrative, documentary, and experimental works and a focus mostly (but not wholly) on films and videos made in California between the 1950s and ’80s.

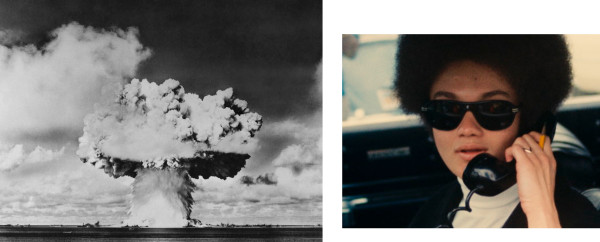

The first light on the Crowley Theater screen was a 35-minute series of flickering explosions constructed in 1976 by pioneering San Francisco assemblage artist and found-footage filmmaker Bruce Conner. Consisting entirely of government-filmed, black-and-white footage of the first underwater atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946, Crossroads shows the same explosion many times from different vantage points and at different speeds ranging from normal to extremely slow motion. Its duration, repetition, and accompanying music by Patrick Gleason and Terry Riley turn the historically loaded, destructive spectacle into a larger meditation on opposing forces, stillness and movement, presence and absence. From out of the luminous atomic plumes, the program cut to the human scale and vibrant color of a street-level documentary made by legendary French filmmaker Agnés Varda during her time living in California in the late 1960s. The 30-minute Black Panthers observes a 1968 Oakland rally to free activist and Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton, who’d been jailed for the killing of a police officer. “This is neither a picnic nor a party,” Varda says in the film’s voice-over, “It’s a political rally organized by the Black Panthers—black activists who are getting ready for the revolution.” Especially after the events of May ’68 had failed to bring about real revolution in France, Varda was particularly intrigued by the rising wave of dissent and mixture of cultural and political rebellion in the United States at the time. The film captures speakers, musicians, and attendees at the rally, as well as interviews with Kathleen Cleaver and Newton himself (in prison) about the influences, ideology, and goals of the movement. Though seen through an outsider’s lens, Black Panthers is a frank and intimate photographic document.

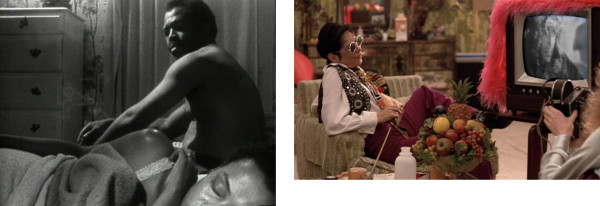

CineMarfa presented special screenings of three very different narrative feature films made in Los Angeles: one from the ’60s, one from the ’70s, and one from the ’80s. Made shortly after completing her Black Panthers documentary, Agnés Varda’s Lions Love (and Lies) (1969) somehow works beautifully as both a funny satire of decadent artifice and a ballad of disorientation amidst harsh realities. Viva (of Warhol Factory fame), James Rado and Gerome Ragni (creators/stars of the rock musical Hair), and Shirley Clarke (New York underground filmmaker) star as versions of themselves making a film in a rented apartment in the Hollywood Hills. This meta-cinema experiment doesn’t exactly present a film-within-a-film, but rather it ingeniously acts as its own cracked mirror, continually breaking and questioning the film’s reality as it’s formed.

An often overlooked gem of independent cinema selected by Thomas Beard (founder of Light Industry and programmer for the Film Society of Lincoln Center) shifted the festival to intimate and intense realism. Director Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1983) is a compassionate portrait of an African-American family living in Watts and breaking down under the strains of economic hardship. Originally from Dallas, Woodberry enrolled at the UCLA Film School in the ’70s and became part of the Black independent film movement known as the L.A. Rebellion. Filmmaker Charles Burnett, whose Killer of Sheep (1977) is probably the most acknowledged work of that movement, wrote the screenplay for this film and did its striking black and white cinematography. It’s a powerful, wrenching experience that leaves one with lasting impressions of even its smallest moments and gestures.

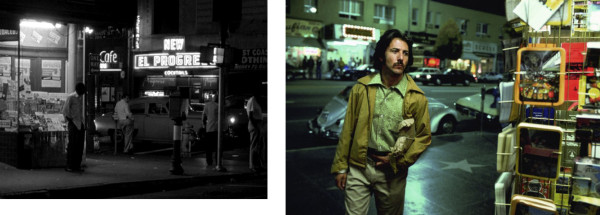

Selected for the festival by filmmaker Harmony Korine, Straight Time (1978) was a passion project for actor Dustin Hoffman and was to be his directorial debut until, days into shooting, he handed over director’s duties to Ulu Grosbard so that he could focus on his performance in the lead role. Based on a novel written in prison by Edward Bunker (whom at age 17 was the youngest ever inmate in San Quentin State Prison), this story of an ex-con’s failed attempts to go straight is inhabited by great performances by Hoffman, Harry Dean Stanton, M. Emmet Walsh, and a young Gary Busey in his first screen role. While this was the most mainstream film at CineMarfa, Straight Time’s complex tensions and dark questions about environment and one’s ability to change rang loudly in the context of other films in the festival.

The interesting connection of place among these three disparate movies was further expanded upon by a screening of Thom Andersen’s fantastic montage film, Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003). Comprised entirely of film clips spanning the history of cinema, this epic film essay explores the ways in which the city has been portrayed as a backdrop, location, and character in films. Andersen points out the tenuous relationships between Hollywood and the real Los Angeles, digs into the manipulations and false contexts given to his hometown’s architecture and cultural life in movies, and finally draws attention to authentic portrayals in lesser-known independent films including Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles and Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts. Not only did Andersen’s film draw a nexus framework for a larger consideration of the festival’s Los Angeles-made narrative films, but its creative interrogation of culture and place through found-footage assemblage connected it in ways to Bruce Conner’s Crossroads on opening night and to the overall programming approach of CineMarfa.

The festival featured a number of great West Coast experimental film and video works made between the 1950s and ’80s—most of them in San Francisco—in two curated programs. “California Void,” assembled by filmmaker/curator Craig Baldwin and presented by his long-time cohort Bill Daniel, conveyed the irreverent spirit of the San Francisco scene in the ’70s and ’80s and highlighted its oppositional socio-political interventions. Among the program’s raw film documents, processed video imagery, punk poetry, and street theater protests was Ant Farm’s Media Burn (1975), a video documenting the group’s infamous public collision of a modified ’62 Cadillac through a pyramid of burning TV sets. Best known for their Cadillac Ranch installation in Amarillo, the group began planning this grand mass-media critique when Ant Farm founders Doug Michels and Chip Lord were visiting professors at the University of Houston. It took place in a parking lot just outside of San Francisco on the 4th of July, 1975, and the video includes its introduction speech by JFK (Doug Hall) about the destructive force of media monopolies, as well as commentary from a number of extremely confused reporters covering the event for local TV news stations.

Delving into earlier experiments, CineMarfa’s “Expanded Cinema” program included 16mm prints of films made between the 1950s and ’70s, many of which had a tremendous effect on generations of West Coast experimental film and media-makers. I have a great fondness for Harry Smith’s kinetic, mystical collage film, Film #10 (1957) and Bruce Baillie’s reflective, single-shot All My Life (1966). But it was two influential works of “visual music” in the program that really stood out. James Whitney’s Yantra (1957) is a complex work of handmade abstraction influenced by the filmmaker’s spiritual interests and involving many years of work to meticulously paint and animate dot patterns and hand develop and solarize the footage. Fellow filmmaker Jordan Belson gave the film its soundtrack, syncing to it an excerpt of experimental music by Dutch composer Henk Badings. A decade later, experimental filmmaker and light show artist Scott Bartlett combined a series of image loops with a droning electronic soundtrack to create his hypnotic Off-On (1967), a classic of existential psychedelia and a pioneering use of combined film and early video processing techniques.

Festival co-founder David Hollander curated and presented the “Expanded Cinema” screening as well as organizing a related art exhibition that he’d long been anticipating: the first ever solo exhibition of visual art works by San Francisco filmmaker Jordan Belson. Belson is best known for his otherworldly, experimental film abstractions, including Caravan (1952), Mandala (1953), Allures (1961), and Samadhi (1967). He also worked with composer Henry Jacobs in the late-’50s to organize the Vortex Concerts at San Francisco’s Morrison Planetarium. Some may also know that Belson was commissioned to create special sequences for the feature film The Right Stuff. However, his drawings, paintings, and objects went largely unseen during his lifetime. Hollander worked with Belson’s estate to select a number of really beautiful, small paintings and one sculpture made between 1955 and ’61 for exhibition at Marfa’s Eugene Binder Gallery during the festival. I can’t express how special it was for me to be able to view Belson’s subtle works (apparently some created by his delicately blowing pigment onto them) on the same day as seeing a selection of films by his contemporaries. (I was also able to visit an unrelated exhibition at Ballroom Marfa which serendipitously included a looping installation of the 1942 film Radio Dynamics by abstract animator Oskar Fischinger, a major inspiration and help to Belson and other filmmakers included in the “Expanded Cinema” program.)

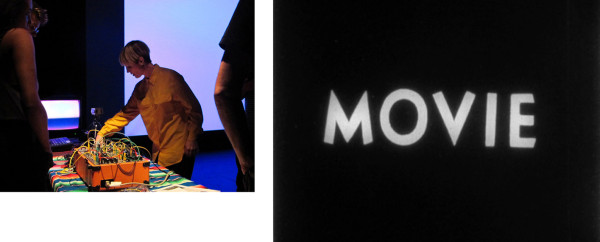

CineMarfa’s diverse and historic California-themed programming also nudged my experience of the festival’s contemporary inclusions, with Bruce Conner films relating unexpectedly to two extremely different new films. Seeing Conner’s Crossroads the night before Dallas-based filmmaker Peter Bo Rappmund’s visual study of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Topophilia (2015) influenced my appreciation of the newer film’s use of time and the simultaneously beautiful and troubling intersections of man-made constructions and natural landscapes. Belgian group Leo Gabin’s anarchic adaptation of A Crackup At The Race Riots was helped greatly by the festival’s deft programming of Conner’s A Movie (1958) immediately before it, placing the newer You Tube-sourced assemblage film within a larger history of creatively reorienting popular media. The festival’s Video Synthesis Workshop, conducted by Los Angeles video artist Jennifer Juniper Stratford with her custom modular video box, connected to image processing seen in experimental works such as Bartlett’s Off-On (1967) and Tuxedo Moon’s Hugging Earth (1985). And though the workshop was an accessible, fun, and rather simple collaboration, under CineMarfa’s cinematic spell I couldn’t help but think about larger metaphorical interpretations of the concepts of image synthesis and feedback. In its sixth year, CineMarfa continued building layers of connections upon its impressive, ongoing program through really smart and playful placement of our media mirrors.

CineMarfa 2016 took place May 5-8, 2016.