In conjunction with the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s virtual cinema series is featuring a limited online run of the film Bless Their Little Hearts, streaming through August 30. Made between 1979 and ‘83, it’s one of the great films to emerge from the community of young, independent filmmakers of color in Los Angeles in the 1970s and 80s that later came to be known as the L.A. Rebellion. Charles Burnett’s 1977 film Killer Of Sheep has become one of the most highly regarded of the L.A. Rebellion films, but too few are aware of this gem that followed it — a collaboration of Burnett and director/editor Billy Woodberry.

Bless Their Little Hearts opens with the sound of a crackly jazz record — Archie Shepp and Horace Parlan’s rendition of the song “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” — while we see Charlie Banks waiting in lines and filling out forms at the unemployment office. Those first minutes set the tone and situation of this slow, sparse, black-and-white blues. In long-take shots and film grain textures, we find hope exhausted along a tale of odd day jobs, late bus rides, abandoned factories, and strained expectations in Watts. The film is about lost roles, place within displacement, and faucets closed tighter than they should be. Because it is slow, intimate, and imperfect, and because the film doesn’t judge, pose, or close, moments from Bless Their Little Hearts have resonated with me for years after first seeing it.

During the virtual revival of this unique work of neorealist cinema, I caught up with the acclaimed filmmaker Billy Woodberry by phone from Lisbon, where he is currently living and working on a documentary. In our conversation, he told me a bit about his Texas childhood, his film influences, his time at UCLA, and the genesis of his first feature film.

Woodberry grew up in South Dallas in the 1950s and ’60s — “deep South Dallas, at the end of the streetcar line,” as he put it. He lived in the Turner Courts housing projects and then nearby Oak Cliff. He recalled hearing blues coming out of cafes near his school, music blaring from a big honky-tonk just beyond his apartment building, and KLIF on the transistor radio, as well as seeing popular movies of the day with family and friends — Epics, Dramas, Westerns, etc. “I saw all those things. But I didn’t understand it. I didn’t understand that they made those things.” Young Billy Woodberry was interested in other things. “My mother wanted me to play music. But I didn’t want to be in the band, I wanted to play sports! I was deep into the lore of Texas football culture.”

His serious interest in cinema began around 1970 while attending Cal State Los Angeles, when a summer course on Cuba introduced him to a new kind of filmmaking. “The teacher was excited by what was happening in the new Latin American cinema at the time, and he decided to teach the course through cinema. That’s where I discovered politically and socially engaged films. The fact that you could do that was interesting to me. You could communicate and contribute. And you could justify yourself to your more militant and radical friends.” It was a fertile time for new voices and approaches in world cinema, and Woodberry’s interests quickly grew to encompass the Brazilian Cinema Novo movement and new African filmmakers such as Ousmane Sembène. “All of that was exciting, because those films were made in a way that you could see the invention. You could see the ‘handprints,’ as I say. It was handmade, not industrial product. They were using the language in a different way.”

Because of his particular interest in Brazilian film, Woodberry was introduced to the young Brazilian filmmaker Mario DeSilva, who was finishing his thesis film at UCLA at the time. DeSilva showed him around the school and encouraged him to apply for the graduate film program. He also insisted that Woodberry ought to meet Charles Burnett. “He thought this guy Charles Burnett was something genuine, original, and really sort of connected, and trying to do something unique and different. He said ‘If you want to learn, there’s the guy you should know.’”

Woodberry enrolled in the graduate film program at UCLA and joined a vibrant, evolving community of filmmakers that was anchored in UCLA’s Ethno-Communications program — an initiative established in the late 1960s in response to student demands that the film department be more responsive to communities of color. The department became a unique refuge, resource, think tank, and collaborative laboratory for studying and creating cinema relevant to communities and issues long absent from the silver screen. Woodberry told me about the communal vibe. “When you arrived at the school and in that community, you were encouraged and were expected to work on the films of others. That was the way that you got to meet people, and establish reliability and credibility, and learn a lot of things with others — not only at school. And there was this idea that whatever you did should be relevant or somehow relate to ‘life in the community’.”

He befriended student filmmakers such as Haile Gerima and Larry Clark. He became involved in the Third World Cinema group — a student-run cine club. He was attending repertory film programs around town, and connected with Black community-based theater groups and cultural projects in Southwest and South Central Los Angeles. He began working on other students’ films, and making his own shorts. And though it took a year or so, Charles Burnett, by then an elder of the department, eventually became a good friend, mentor, and collaborator. “We started to see each other and become friends. He would come to my house and we would screen films on the wall and talk about books.”

About the beginnings of Bless Their Little Hearts, Woodberry told me, “I needed to make a thesis film for graduation, and I was thinking ‘I’m not such a great, original writer but maybe if I have good material, a good basic story with some substance, we can make something beautiful.’ I was thinking of adapting a story by Faulkner called Evening, which actually kind of follows the logic of the song,‘St. Louis Blues.’ Charles had made a short movie up north of Los Angeles called The Horse and we were thinking we might use that location for it, and pretend it’s the South. We used to do all of these drives, and talk and talk and talk. But I was saying that I didn’t know if I could manage that story, and eventually he told me, ‘Okay, I have a story for you — the kind of story and characters you’re interested in, and I’ll write it for you.’”

Burnett had been inspired to write something after seeing men selling fish on the side of the road. He offered Woodberry an original 70-page scenario, agreed to do the cinematography for the film, connected him with people for the cast, and then granted Woodberry the freedom and trust to develop, direct, and edit the project his own way. The result of this unique collaboration is a work of intimate and intense realism that is related to Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, yet different. “He wrote a story that was not the same, but in a similar milieu. I wanted to honor the material and to get it right. But I didn’t want to make the same thing as him.” I wondered if the collaboration was at all uneasy, but he said that Burnett was wholly trusting and continually supportive. “There was a real respect… . He really made sure he was allowing me to direct it.”

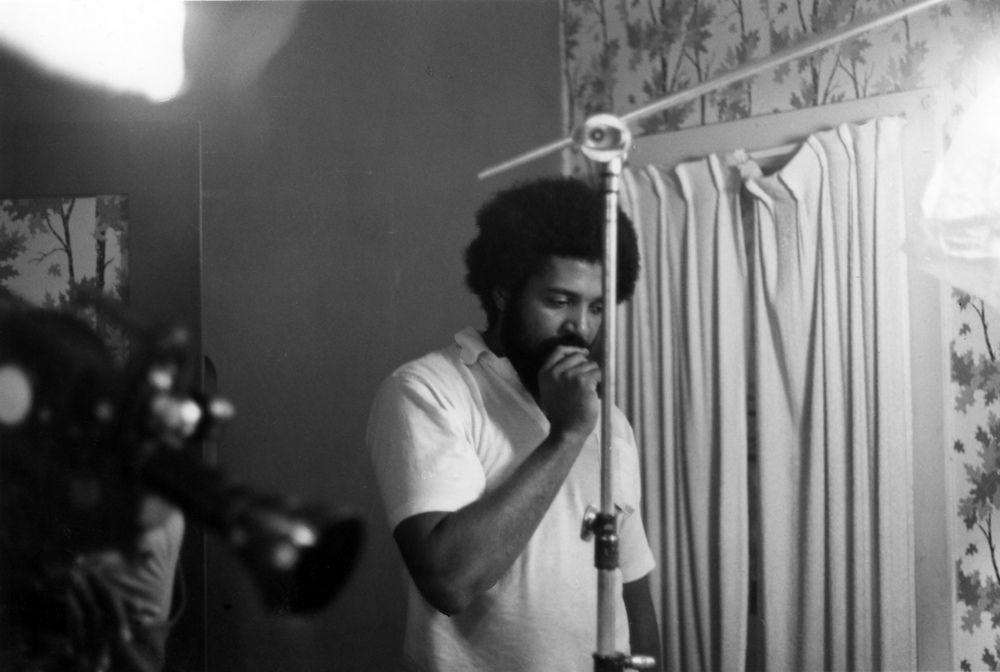

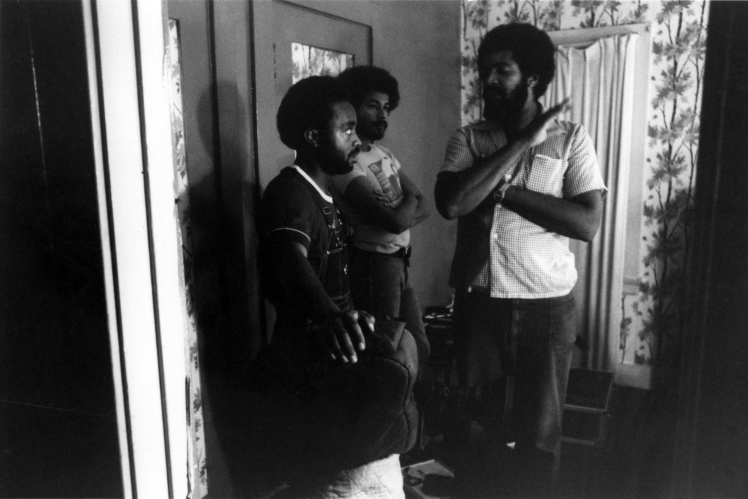

Billy Woodberry directing a scene with (left to right) Kimberly Burnett, Angela Burnett and Kaycee Moore. Cinematographer Charles Burnett is at the window.

The film’s main character Charlie Banks is played by Nate Hardman, and Charlie’s wife Andais is played by the great Kaycee Moore, who had previously appeared in Burnett’s Killer of Sheep and would later appear in Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust. While most of the film was scripted, a powerful and devastating scene in which Andais confronts Charlie in the kitchen was completely improvised and filmed in one long, handheld shot in the uncomfortably tight and charged space. While they are not the film’s central characters, the young Banks kids are the central concern — the “little hearts” of the story. Woodberry told me that, despite some misinformation about this, they are not Charles Burnett’s own children but rather his nieces and nephew. “The older two of them had been in three films with him. They’d been in his films since they were little, and so, actually, they had more experience than the main actors. They knew how to respond.”

I asked Woodberry about the film’s great use of music, and he told me that he’d spent a lot of time considering that — sometimes making selections for reasons that aren’t immediately apparent. “The song ‘Lost In A Dream’ seemed right, but also there’s the biographical fact that Esther Phillips is from Texas. She grew up in Houston, then she came to Los Angeles. So that gave me a connection to something. Most of those people in Los Angeles were from Louisiana and Texas, and I wanted to connect with all that stuff.” He also mentioned the blues and spiritual songs performed by Archie Shepp and Horace Parlan. “[Shepp] wasn’t known for this kind of music. He was one of the inventors of the Free Jazz thing and was really radical, and then at a certain age he started to be more reflective and started to play this kind of classic blues. He just decided ‘no showing off, I’m just going to play this,’ and he’d play ‘Going Home’ and those things. Those are spirituals — ‘slave songs,’ as they say. I think it gives something to the film, it gives it a kind of depth.”

Seen from the vantage point of 37 years later, Bless Their Little Hearts carries added layers of context. “Unfortunately, the subject matter of the film is too all-pervasive for too many people, that it’s almost normalized now,” Woodberry said. “If we come to accept that tens of thousands of people are sleeping on the streets of Los Angeles in tents, then we’re accepting a lot.” He also brought up the transformations that occurred in Los Angeles and other cities soon after the film was completed. “When we did it, it was right before the explosion of all that stuff that turns up later in the films Boyz n The Hood and Menace II Society. It was in the early ’80s, just before this massive displacement and redundancy of people, and before these ‘other employment opportunities in retail’ came in. That was deadly. Very destructive and heartbreaking. We just sensed it. We were telling the story of the ones who wouldn’t be in that game.”

I think it’s important for contemporary viewers to remember the miraculousness of Woodberry, Burnett, and others in that creative community at UCLA collaborating to make relevant works completely outside of Hollywood’s ideals, aesthetics, and infrastructure. Truly independent films were nearly impossible to make at the time, and equally difficult to get shown. That’s why, despite being considered a pioneering, essential film in the neorealism strain of the L.A. Rebellion, Bless Their Little Hearts has been more often talked about than seen in the nearly four decades since it was completed. I’m grateful for the MFAH’s online presentation, bringing the film to the attention of more audiences, and I’m grateful for Billy Woodberry taking the time to speak with me about it.

‘Bless Their Little Hearts’ streams through August 30 ($4.99 for 3-day rental, supporting MFAH Films). Please go here for access.

1 comment

Awesome piece! Very excited to watch this!