He that cuts off twenty years of life

Cuts off so many years of fearing death.

Julius Caesar, Act III, scene 1

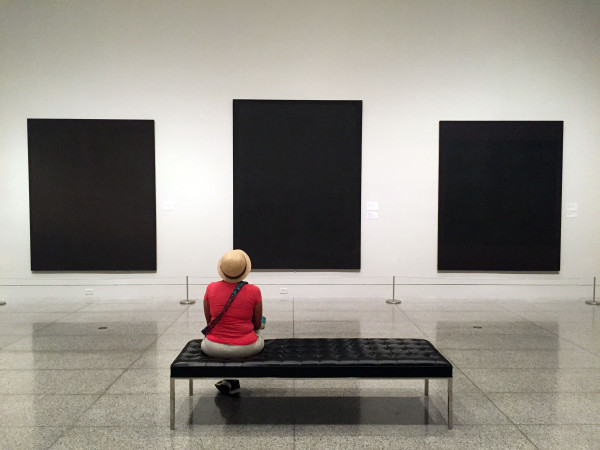

Have you ever noticed how Rothko always gets a bench?

A fellow critic brought this to my attention some months back. He had recently visited the Phillips Collection, and he was amused by the contrast in their presentation of various artists, writing to me: “Jacob Lawrence’s tour de force Migration panels and perhaps the best Bonnard in the world? Not good enough for a bench. Four Rothko works? Two benches and a sign encouraging only four people in the room at once, to maintain the solemnity of the experience.”

Ah yes: the solemnity. We mustn’t have any laughter around the Rothkos. During his lifetime, Mark Rothko was regarded as perhaps the ultimate small-r romantic painter: a tortured, heroic shaman-artist who had figured out a way to channel the unknown in his color field paintings. That mythology has calcified into dogma in the years since he committed suicide at the age of 66, in 1970. To look at one of Rothko’s mature paintings in his signature style is to experience transcendence, we are told, and one is expected to approach his work with the patient reverence of a feudal serf regarding a medieval altarpiece (and for the same reason). These are Very Spiritual Paintings, these are Holy Relics, and the problem is you if you’re not transported to the beyond while looking at Them. And so Rothko’s paintings always get a bench—a pew—of their own.

The Rothko Room at the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.

Put another way, imagine there being a bench in front of Duchamp’s Large Glass. Or Rauschenberg’s Monogram. Or, closer to home, Chris Burden’s masterful submarine piece at the DMA or the Surrealism galleries at the Menil Collection. Those works don’t get benches, but Rothko’s instantly recognizable, fuzzy rectangles of color are demarcated for extended contemplation, with benches almost reflexively placed for the viewer’s solemn contemplation and spiritual uplift. Of course, there is a difference: the other artists I mention all made work about living. Rothko is all about death.

Hence the religiosity. We may have moved as a Western society away from literally believing in ancient mythologies, but we still crave a visual aid to calm our fears about the ultimate unknowable. When Nietzsche (one of Rothko’s favorite authors) said God is dead, I wonder if he realized how quickly humankind would seek out a replacement. God may be dead, but Rothko’s paintings (and by extension, Rothko himself, the tormented, suicidal genius), are a whole new religion for art world secularists. People used to believe that heaven literally looked like Correggio’s dome in Parma. Now they believe it literally looks like a Mark Rothko painting.

“Can anything be…further away from the razzle-dazzle of contemporary art, the frantic hustle of now? This isn’t about now; this is about forever. This is a place where you come to sit in the low light and feel the eons rolling by, to be taken towards the gates that open onto the thresholds of eternity. To feel the poignancy of our comings and our goings, our entrances and our exits, our births and our deaths, womb, tomb and everything between. Can art ever be more complete, more powerful? I don’t think so.”

– Simon Schama’s Power of Art: Rothko

Of course, the 16th-century people of Parma probably didn’t think so either when they looked up into Correggio’s dome. Simon Schama’s reverential 2006 documentary about Rothko, from which the above quotation is taken, also includes the following dramatic reenactment of the artist talking about his work:

Where are the origins of this inanity? They lie in the horse’s mouth. If Duchamp said he was an agnostic who didn’t believe in “all of art’s mystical trimmings,” Rothko is the opposite, saying that “pictures must be miraculous” and “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on” (ignoring the fact that tragedy, ecstasy and doom are neither basic nor emotions). Rothko also preemptively dismisses any viewers who dislike his work: “A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer. It dies by the same token. It is therefore risky to send it out into the world. How often it must be impaired by the eyes of the unfeeling and the cruelty of the impotent.” Here we see the origins of the herd mentality of Rothko-worship: if stupid people can’t see his clothes, we’d better all nod in agreement when he declares how great he looks.

The irony of Schama’s widely accepted point of view—that Rothko stands pure and apart from the “razzle-dazzle,”— lies in the hard, cold fact of the prices his paintings fetch at auction. Selling miracles has always been good for a buck, and like all religions, Rothko is very big business. Just look at MarkRothko.org, with its headline shouting the latest sale price and its column of posters with the captions “BUY NOW.”

To imply that our perception of Rothko has nothing to do with the horsetrading that has gone on ever since the ugly events around the artist’s ugly death, is to turn one’s back on the world we all live in—which of course is one of the primary attractions of any religion. The razzle-dazzle of contemporary art? Rothko’s frenzied market lies at the throbbing heart of it.

Of course, the incongruity between Rothko’s offer of unsullied emotion and his hefty market cap is nothing new. The following anecdote from Dave Hickey describes it better than I can:

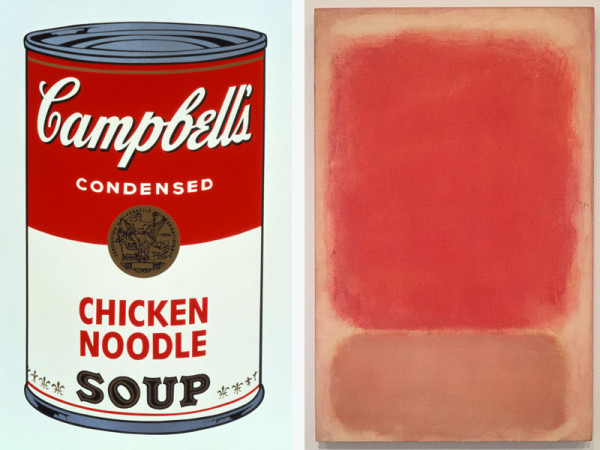

“One evening in the mid-nineteen seventies, I was one of a group of people gathered around Andy Warhol at a cocktail party at the St. Regis Hotel in New York… Since the Mark Rothko estate was much in the news at the time, we were talking about that. At one point, someone brought up the subversive similarity between Mark Rothko’s trademark painting format and Andy’s soup can paintings from the Sixties. This was not a new subject. One of the jokes around the Factory at the time had been the idea that the soup cans were kind of a “modernization” of Rothko’s format—Rothko adapted for assembly line production methods…

That night, we were having a good deal of fun with this subject and with the serene pretentiousness of Rothko’s paintings (for which, I hasten to note, Warhol had a good deal of respect). Since Andy seemed in a particularly gregarious mood that night, I decided to ask him a something I had always wanted to know. “Okay, then, “ I said, “Just what, exactly, is the difference between a soup can and Rothko?” “That’s easy,” Andy said, “Mr. Campbell signs his on the front.”

If we believe Andy’s remark about importance of Mister Campbell signing his soup cans on the front, the soup can paintings may be taken as arguing that what is “hidden” in a painting by Rothko, or any member of the New York school, is not some spiritual insight into the nature of metaphysical reality, but an artist’s “name-brand” signature. By putting the “trademark label” on the back of the painting and the “soup” on the front, Andy felt that Rothko (unlike “Mr. Campbell”) was disguising the essential mercantile character of the painting’s transaction with the viewer in the gallery—the fact that we “buy into” paintings in much the same way that we buy soup—that we select a name-brand product and chose the flavor according to our personal taste.

To deny this, of course, is to transform the practice of art into an aristocratic pastime, an ecclesiastical project, or into academic argument—and many critics and institutions continue to prefer these constructions of art’s endeavor.”

From “The Art Guys Get Legit,” 2000.

“Mr Campbell signs his on the front.” (right: Mark Rothko, Red and Pink on Pink, c. 1953, Tempera on paper mounted on board with acrylic, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, bequest of Caroline Weiss Law)

Unfortunately, these constructions of Rothko’s endeavor, as Hickey puts it, are only fleetingly questioned by the artist’s worshipful retrospective on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. It’s an exhibition of some of the 798 works that were left in Rothko’s studio when he killed himself, and it’s drawn primarily from the National Gallery, where half of the works were donated in 1984. (As curator Alison de Lima Greene said during a tour, “[MFAH director] Gary Tinterow said these were the works Rothko couldn’t sell, and I said they were the works he wouldn’t sell.”)

Even considering how much effort goes into organizing an exhibition like this—especially considering it—it’s hard to muster enthusiasm for a Rothko show these days. To pour energy and money into a preordained blockbuster that caters to generally accepted good taste seems unimaginative at best, and craven at worst. A Rothko show will generate goodwill about its “importance,” because the cult of Rothko has pre-programmed audiences to believe in the stuff. But even by Rothko’s standards (and he was not a very great painter), the MFAH show is undistinguished. These aren’t the Rothkos you’re looking for.

The exhibit opens with a gallery filled with Rothko juvenilia. We see that the artist went through a Surrealist phase, a mythological phase, and an urban scenes phase, which is fine—all young artists explore the work of their predecessors to figure out what they’re doing. But we also see from these unfamiliar figurative works that Rothko wasn’t very good at pushing paint around a canvas.

Untitled, 1937/38, Oil on canvas. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc.

It’s a rather flat-footed start to the show, and the reward we expect, of galleries filled with masterpieces, never materializes. Instead, we have a few spaces of mostly clunky works, almost all of which look better on a smartphone screen than they do in person. Rothko famously always called for dim lighting (people d’un certain âge and middling abstract paintings look better in the half light); but these galleries are brightly lit, which doesn’t do Rothko’s clumsy color modulations any favors:

Untitled, 1949, Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc.

(There are uncharming condition issues with several of the works, including cracking and rumply edges.)

Untitled, 1956, Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc.

Of course, there are benches, and trios of later paintings that echo his trinities in the Rothko Chapel, including the so-called Blackform paintings, which are the alternates for the chapel itself.

The exhibition is accompanied by an audio tour with various contributors, including a yoga instructor. Here are some excerpts:

- These canvases of Rothko’s seem to breathe and yet these colors have a stability in them.

- And if you see with your heart, if you are more in the experience of it, and he actually says ‘a painting is not a picture of an experience, it is an experience’ – Rothko’s paintings seem very simple at first glance, and yet as you sit with them they can be very profound.

- I would encourage viewers to, as they view the painting, to let themselves be absorbed in that experience where it seems, at least for me, that you’re not looking at the painting, but you’re just present in that experience.

- There is something about loss in these paintings.

- Just feel the movement within the stillness of the painting itself.

Only the MFAH director Gary Tinterow, of all people, gets to the heart of the matter in his contribution to the audio tour:

“I think the simplicity of Rothko’s compositions often begs the question, is it the environment? The fact that we are in the rarefied precinct of a museum, or the Rothko Chapel, that adds meaning to these works? And one could ask oneself, yeah I think legitimately, if you were to take one of these paintings and put it on a truck and put it outside the museum door, would it still hold up? Would it still be compelling? And it’s to me a perfectly valid question. The context really matters, but I think there is something inherent and integral to Rothko’s work that holds our attention, that makes them compelling, that has us coming back always for more. It’s clear to me that Rothko himself didn’t always understand what he was doing.”

(Tinterow tacitly ignores the fact that many art enthusiasts might not keep coming back for more Rothko, if it weren’t being continually foisted on them.)

In the middle of the audio tour, we are directed to listen to the second movement of Mozart’s clarinet concerto—a piece of music I have loved since it was featured on the soundtrack of the movie Out of Africa some 30 years ago. Tinterow sets the scene: “The second movement of Mozart’s clarinet concerto has often been understood as an expression of Mozart’s loneliness… Rothko enjoyed listening to it while contemplating the color harmonies of his paintings.” Tinterow then encourages us to choose a painting in this gallery as our focus as we listen to the music (and presumably contemplate its color harmonies, as opposed to contemplating a young Robert Redford and Meryl Streep enjoying a romantic safari dinner, which sounds like a lot more fun).

Untitled, 1956, Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc.

As much as I love Mozart’s adagio, here it comes off like a Saturday Night Live parody of the sanctimoniousness of the art world. It’s the Marina Abramovic of museum audio tour moments. To be fair, a roomful of Rothkos indeed looks lovely when listening to Mozart’s sublime music. But Ross Dress for Less would look lovely listening to it, and we’ve all seen plenty of great art that doesn’t need a backup band.

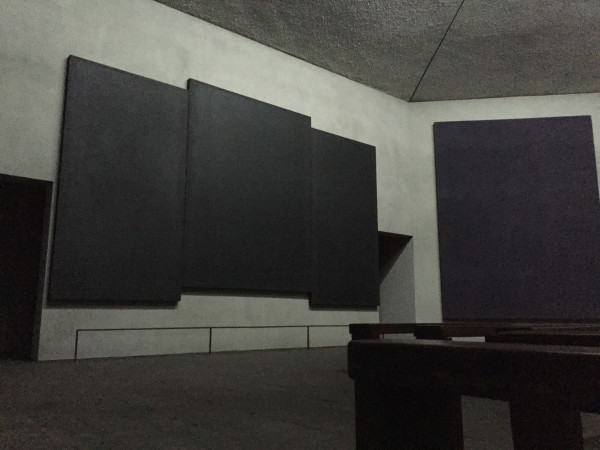

Perhaps it was inevitable that the MFAH do a Rothko retrospective. The artist looms overly large in Houston because of his eponymous non-denominational chapel, commissioned by Jean and Dominique de Menil in the late 1960s and completed in 1971. I visited the chapel recently on a cold, wet day, when the miserableness of the architecture and its contents was acute—but then again I find the place dreary even in glorious weather. It’s a depressing space, the last gasp of a suicidal imagination bent on checking out.

Even Simon Schama can’t wax rhapsodic about the Chapel: “Tanks of ink have been spilled trying to convince us that this place is not as dark and funereal as it seems. But quite honestly, sitting here, do we feel bright and beautiful? I’m not sure… Good luck, and Good Night?”

In stark contrast to this view is Rothko Chapel director David Leslie, whose contribution to the audio tour at the MFAH includes this zinger:

“The core essence… of the chapel is invitational, and might be captured in the two words ‘radical hospitality.’ In Texas talk we would say “Y’all come,” but it’s that radical hospitality that’s saying… come and be part of this amazing movement.”

Y’all come? I can think of many things the Rothko Chapel communicates, but “y’all come” is not among them. As Thomas McEvilley said, “Rothko’s chapel paintings were to show ‘the infinity of death.’” That’s the whole deal. It looks like a mausoleum because it is one. Again, Simon Schama: “It’s hard not to feel the Houston chapel isn’t kind of live burial, an internment, not just of Rothko’s future, but of his hopes for art.”

Back to the exhibition at the MFAH, the final piece de resistance comes at the end, when the congregation is funneled out into a truly risible pop-up gift shop, complete with stacks of Rothko books and little piles of colorful, Rothko-y tchotchkes. The romantic myth of genius has been boxed up for us, bands of color with a tasteful boutique sensibility.

Imagine if Mark Rothko hadn’t committed suicide. How much of his legend is tied up in his suffering, his embodiment of the tortured artist archetype? How much would we care about his paintings, assuming there wasn’t a foundation in his name whose existence depended on the constant, careful grooming and packaging of his mythology? My guess is that he would have faded to the ranks of a Franz Kline or a Motherwell—good enough, but not that good. Of course if that had happened, we would most likely have found another artist to worship, another conduit to heaven.

But if you saw this exhibition and privately wondered whether you were missing something, or personally lacking in depth, because you didn’t feel a thing looking at those pictures? Well, you’re not alone.

And knowing you’re not alone is the best kind of spirituality.

Correction 12/22/15: the original version of this article misspelled the name of an artist. It is Franz Kline, not Franz Klein.

25 comments

jesus h christ… thank you. finally

You forgot Johns’s Periscope.

http://www.jasper-johns.org/periscope.jsp

If that’s not a Rothko satire, then I don’t know what is.

Wow!

MOCA had a bunch of Rohkos, sans benches I think, and wall text explaining Rothko intended viewers to get close to his paintings so that the paintings would fill the field of vision. The displayed paintings were some of the very few in the entire museum to have black tape guides on the floor indicating “stay the hell away from these paintings!”

Also:

Andrea Fraser video exploring self-guided tour of Gugg Bilbao: https://vimeo.com/56939001

Wow. Thank you for saying what I felt. The Chapel is the place known for artist’s memorials… i.e. Dorthy Hood and Dick Wray (who would have loudly protested).

The show did not disappoint my expectations.. it was a total let down. Best go up stairs and see Pleasure and Piety: The Art of Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638).

Probably the best and only honest dissection of the “cult” of Rothko ever written. Good job Rainey! I love Rothko’s for the nice colors and forms. He was part of the NY AB/EX crew. But the doom, gloom, and shamanism are “art world” fabrications. Like you said, look at the prices and the gift shop…And as allways, Andy’s comment is simple, hilarious, and so true.

This was a terrific review, Rainey. Thank you.

I think the cult of Rothko may have begun (or was at least abetted) with a book by the widely respected historian Robert Rosenblum, “Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition,” published just five years after Rothko’s death. In the book, Rosenblum asserted that Rothko had succeeded in painting the Kantian notion of “the sublime” like no other artist before him. Others, notably Caspar David Friedrich – then under the spell of Kant’s somewhat recent aesthetic philosophy – had tried (and failed according to Rosenblum) to produce a work of art that facilitated the human mind’s transcendence of its earthly trappings. According to Rosenblum, Friedrich’s failure was rooted in his inclusion of compositional elements that were recognizable to the human mind, which allowed the viewer to project his or her memories and life experiences onto the work, and thereby prohibited the alleged opportunity for transcendence. Think of his famous “Monk by the Sea,” where the little monk on the shore gazes into the dark abyss. When one looks at this painting, instead of focusing on the great expanse as was intended – again, according to Rosenblum – all one sees is the monk. Rothko, by contrast, in removing everything that was recognizable, allowed the viewer to experience the work without noisy thoughts and memories interfering with it. Presto! Opportunity for transcendence! Have a nice trip! Of course, drugs might work too.

Next time, try listening to death metal instead of classical. It’ll totally change the experience.

Great piece as always! I had the pleasure of hanging out with Sasha Yunkers, the daughter of Adja Yunkers and Dore Ashton last week and heard some great stories of her perspective growing up around Rothko. Everything she shared was right in line with this article:) He daily lived in the doom and gloom.

Thank you Rainey. I thought I was the only one.

I don’t understand this effort. Commiseration? Frustration? Validation? Fear? This is rational world propaganda. If you want to feel you shouldn’t give your all to thought. In the least, you could focus your effort to the chapel, the bench, your associations, pretensions, etc. Everything surrounding the work. You don’t have to huddle up with other narrow minds. That Hickey/Warhol story is silly. To perceive and appreciate the charge of a Rothko painting doesn’t have to be as solemn as you think it does. Don’t over-compensate a skepticism and opposition of all things serene and spiritual and divine by being profane and bigoted. If you channeled your energy you could really do something.

I was hoping for a comment like this; thank you. At one point in a draft of this essay I had a sentence about sincerely believing in the spiritual power of art (which I do). I just don’t believe in the spiritual power of *Rothko’s* art, and the generally accepted notion that his paintings are a gateway to the sublime (a different “huddling up” of narrow minds, if you will). Like all tribes, the art world can be pretty reflexive, and once a dogma is established (Rothko is spiritual; Hirst is a hack; Judy Chicago was onto something with ‘The Dinner Party’), people seem to toe the party line without questioning it. And didn’t we all come to art to get away from conformity, and hopefully have some fun?

Of course, exactly what “the spiritual power of art” means is subject to a quibble.

Welcome. And thank you, too.

Oh my! Haha. I almost TLDR this but I had to see it through. I have had a mixed and ever changing view of Rothko from the first time I saw his bright field paintings in Arkansas as I was growing up. They charmed me. Then when visiting the chapel at first I was appalled… The heat in Houston is so oppressive the cool dark place the paintings can hardly be seen in was filled with the droning sounds of a struggling HVAC system…. I didn’t get it. But as an adult I have gone back and gave it a second chance. To go back to what you said about music… Not every masterpiece needs a soundtrack BUT I discovered the chapel has amazing acoustics which are part of what startled me at first. When music is played in the space it really is impressive. The paintings don’t clash with anything, they simply seem to magnify whatever you are thinking/feeling which can be extremely refreshing in a totally distracted world. Full disclosure… I got married at the chapel. Houston was a great place to gather our far flung families and the chapel that often hosts memorials was kinda hard to explain to my traditional family, no flowers, what? They had nothing to judge or be distracted by but the words, music and the ceremony at a place that gives me the feeling Im sitting on the edge outer space. Maybe I’m brainwashed about my love of the Rothko Chapel, but you can say what you like about Any famous artist and gift shop commercialism.

Fun and valuable though this article may be, it’s bit crass to use the website markrothko.org as part of its line of attack. It’s pretty clear it has nothing to do with the Rothko Foundation. It’s just someone trying to make a buck by a commission on sales referred to Amazon or Art.com. Related to the same site are: paulkleepaintings.org , michelangelo.net, etc. The fact that there’s a market for Rothko, whether at auction or in reproduction, does not reveal anything in particular about the work or the man. What I’m interested in is whether the kinds of “slow art” viewing experiences that an artist like Rothko, or even Sarah Sze for that matter, can be presented alongside art of the faster, more commonly produced, “sound-bite” kind without some sort of bench to clearly signal that a quick glance is not going to be enough to “get it.” I agree the presentation doesn’t have to be pompously hallowed but does just having a bench to sit on really do that?

Franz Kline not Klein.

Yes. Danke.

“How much of his legend is tied up in his suffering, his embodiment of the tortured artist archetype?”

Lemme see….how does 95% sound? Then there is the other 70%…..clinical depression and chronic schizophrenia. (Narcissism, often, is a component of the latter.) Rothko was on the spectrum for mental illness. The list is long.

Alas, he longed for the past……sawdust on butcher shop floors, ice blocks atop cheese crates……clotheslines in the back of three story apartments. And no money. In short, the good oulde days.

Dare I mention this was Williamsburg, Brooklyn , circa late 1940s/early 1950s. Rothkoville.

And somehow we turned Rothko’s work into a religion. And fifty years later we did the same for Apple.

What is needed now is a another chapel….. dedicated solely to IPhones. And benches from which to peer up at them hanging on the wall.

A great essay Ms.K.

I actually liked the comparison with Warhol. Neither man could paint well. Both became larger than the sum of their parts after their passing.

My favorite moment in time with regards to Rothko’s work was when Francis Bacon saw one for the first time and said: “I don’t get it.”

Maybe Bacon needed to be seated on a b….

Fifty years later and I am still waiting for spiritual enlightenment when I gaze at one of his works. I don’t get it either. Seated or standing.

Fortunately, there is Pollack. Each to his own.

.

Ok, now a pilgrimage to Marfa? 😉

“Friendship … is born at the moment when one man says to another “What! You too? I thought that no one but myself . . .”

― C.S. Lewis

Loved the link to Ross Dress for Less — it’s a rare treat to laugh out loud while reading an art review. Yes, audio tours can drain the room…

Really good essay, Rainey, and your subsequent comment about spirituality in art is intriguing. It made me think back to several visits to the Rothko Chapel, beginning in the early 70’s when I was a student. That first visit WAS a spiritual experience. But then, I’m just as likely to have a spiritual experience standing in line at the grocery store. Later visits were perhaps bolstered by nostalgia, but last year the Chapel let me down. Surfaces were shabby, the purple in the paintings seemed gone, and the architecture just felt, well, dated. But worse, the sense of place was more pretentious than reverent. Do other longtime visitors sense these changes?

It’ll be interesting to see what happens at UT Austin with Ellsworth Kelly’s upcoming building, the chapel-that-can’t-be-called-a-chapel, which has even more obvious religious iconography than Rothko’s. Will it too become a shrine?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8h11-Jm4-s

“You could be seduced to think that art can redeem the world. It can not.”

Anselm Kiefer

Rainey, again you underwhelm me.

I found this refreshing since I like rethinking received ideas, especially those that masquerade as dogma. I cam imagine similar things being said about the 19th century giants when impressionism stormed the gates. I wonder what will happen when Rothko falls off the throne? Perhaps, Mr. Rainey, you are sensing a bellwether.

Seems like I made the Kline, Klein mistake and my Mr. should have been Ms. This is all the more reason I need glasses and a more reliable Siri. At least Rothko was sympathetic to the blur that my eyes do all too naturally.

Late to the party here, but this is a good example where some additional background in contemporary music might help make sense of why Rothko’s paintings were and are so powerful, regardless of how much they are priced. I suggest reading composer Morton Feldman’s essay “Between Categories” for another perspective on Rothko’s work, one without the dubious religiosity the reviewer is having such a hard time reconciling.