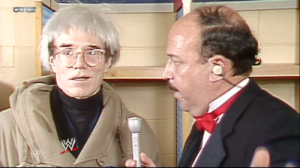

http://youtu.be/deRMRh8Zjgg

The blank “uh” we hear before Andy Warhol’s responses was typical of his interview style but hardly ever appears in his published interviews as it was most likely edited out by the interviewers and/or editors. In the video above, the “uh” seems to represent a sort of passive resistance to the aggressive tone of the interviewer. As both Reva Wolf and Kenneth Goldsmith observe in their introductory texts to I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, 1962-1987, Warhol tends to respond with “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know” when reviewers ask pretentious or long-winded questions.

That Warhol’s technique of answering “uh, yes” or “uh, no” was used over and over again in his interviews indicates that there is something more going on here. In fact, the more one listens to his interviews, the more the “uh” Warhol utters before he speaks stands out. It seems to be more than just a straightforward verbal tick. It acts as a blank space into which we can read unsaid meanings. In the example above, it seems like the “uh” could be interpreted as a “what?!,” “you don’t know what you are talking about,” “that’s what you are saying,” or “screw you.”

Warhol’s “uh” can also be interpreted theoretically as the first move toward the artist’s self-formation through speech. It was the gap or expressionless non-utterance between question and response that highlights the contrivance of the form of the interview at the moment in which it is enacted. It is what Jacques Derrida might call the “trait,” the mark with which Warhol begins to sketch his self-portrait through the interview, or the moment of blindness where what Warhol is saying is detached from himself to leave his own thoughts and become part of the construction of “Andy Warhol, the artist.” Warhol’s utterance of “uh” is therefore something like the verbal equivalent of the ruin described by Jacques Derrida in Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins:

Ruin is, rather, this memory open like an eye, or like the hole in a bone socket that lets you see without showing you anything at all, anything of the all . . . There is nothing of the totality that is not immediately opened, pierced, or bored through, the mask of this impossible self-portrait whose signatory sees himself disappearing before his own eves the more he tries desperately to recapture himself in it (69).

The “uh” is this blank opening through which Warhol stares out, a hole in his author-function that is covered over by the editor’s omission.

This gap, schism, or division between the subjective experience of Warhol as a person and the authoring of his persona as an artist through the interview serves multiple practical needs as it allows him to stand at cross-purposes. As an artist, Warhol was reliant on the values that come with authorship such as authenticity, quality, consistency, and the legal right to his creations in order to sell his work and thereby maintain his ability to keep making art. However, his coy refusal to give frank replies in interviews seems like a refusal of these very authoritative qualities which an interview typically bestows on an artist. Through the simplest of means, in his short responses, Warhol is able to absorb the prestige of being interviewed while at the same time rejecting the scrutiny that normally comes with that privilege.

Michel Foucault reminds us that discourses began to have authors when authors became subject to punishment (Rabinow, The Foucault Reader, 108). In the interview above, it seems that Warhol is being penalized with hard-hitting questions, forced to defend himself and pop art in general, and being deposed for future evidence. Within the context of the interview, Warhol’s evasive replies are a transgression of the interviewer’s interrogation. Also, by this same logic, the interviewer is an author as much as Warhol is. In a sense, there is a double-authorship at play, for the interviewer is writing the artist, who is in turn writing themselves. The questions the interviewer asks set the boundaries for the ideas presented in the interview and their editing can change the way the artist is presented. So if we are using an understanding of author-function in the Foucauldian sense, then the interviewers themselves must also be subject to punishment.

The neutral tone of voice typically used by interviewers conceals their authorship behind the journalistic narrative of what they are presenting. Warhol’s technique of saying “uh” is one way he works to unveil the position of the interviewer to make them the subject of scrutiny. In making the questioner do most of the talking, Warhol flips the format around so that the questions become the focus of the interview. Some other tropes Warhol would use to achieve this same effect were to let those around him, usually his studio assistants, do the talking for him and to record the interview so he became the interviewer himself, as in Emile de Antonio’s interview with Warhol in his 1972 documentary Painters Painting.

In the clips where de Antonio interviews Warhol, some of which are shot through a mirror, Warhol holds a microphone recording his own interview parallel to de Antonio’s. For most of de Antonio’s questions, Warhol turns to his friend Brigid Polk (nee Berlin) to answer for him. De Antonio responds by cutting Polk out of the frame and insisting that Warhol’s art was more original and preceded Polk’s. Yet, Warhol persistently defers to Polk even as de Antonio’s grows visibly frustrated. De Antonio’s annoyance reveals that he has as much at stake in this interview as Warhol and perhaps even more.

Just as the author-function of the artist is meant to validate the authenticity, consistent quality, even genius of their work through the unity of their persona as author, the interviewer is a witness to this persona in an almost legal sense, to confirm the artist as author. The more that Warhol denies being the origin of his work, evades questions about his motivations, and denies the claim that he has any exceptional skill, the more that de Antonio is held culpable as a fraud for upholding Warhol as one of the great New York painters. Warhol’s strategy of resisting and exposing the interviewer points out that the interviewer is complicit in the act of the interview. Just as Warhol might not be able to profit from his artwork if his status as author is called into question, so too would the interviewer look foolish for talking to him. Because both are subject to punishment, the interviewer and artist are caught in a sort of power struggle, yet through all of this Warhol remains detached, calm, cool, collected, and in control.

7 comments

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EDRyW-R–X4

Thanks for the link to Warhol at Wrestlemania. I had not seen the full clip in all its glory

Early in my working life, I worked for a magazine that ran one or two massive interviews in every issue. I had to do a lot of transcribing–sitting in front of a typesetting computer listening to cassettes on a variable-speed tape playback machine. (Which should give you an idea of how long ago this was.) The thing is, everyone says “uh” and “um.” Also, everyone speaks in incomplete sentences or in run-on sentences. As an editor, my job was to turn the chaos of speech into well-formed written prose–while leaving in the personality of the interviewee.

My point is that while Warhol’s “uh” and “um” might have been affectation or deliberate attempts to convey meaning (impatience with the question), they also may simply have been a normal part of his speech, the kind of filler words that every non-media-trained person on Earth uses–especially when faced with a microphone.

It’s a good point that you bring up about filler words generally indicating a non-media trained habit. Given Warhol’s extensive experience with being interviewed and his media savvy, perhaps that could be an argument for the “uh” as an intentional statement

I’ve watched that clip many times, and showed it to students as an example of pop art. Warhol was taking a familar commercial product, the TV interview, and spitting it back as parody, with almost endearing (for Warhol) generation-gap sass. He supresses a conspiratorial smile at one point with only moderate success, but he was young and inexperienced then.

It’s a little known fact that the clip was filmed outside Cowboy Stadium in Dallas, just after the assassination of JFK.

He’s smiling at the funny question, ‘is pop art repetitious’. not being conspiratorial, it appears to me. But I’ve read and re-read both of these posts and I can’t make heads or tails of the point. That the interview may not have the probity of a Vulcan mind meld is common sense. D-Uh. Really, ‘the interviewer is complicit in the act of the interview’? Who would of thunk it. So maybe I’m missing something. Maybe it’s the appeal of jargon and name-dropping, or filler words of another sort.

“Glasstire is an online magazine that covers visual art in Texas and Southern California.”

So… MORE Warhol? There isn’t enough happening in Texas to keep Hooper entertained?