I was talking to a friend recently who told me about an artist who felt affronted when a previously willing gallery owner decided to nix the artist’s show proposal as it got more ambitious and aggressive. The show involved the artist pouring a lot of toxic and/or severely sticky chemical goo over and around some objects and across walls and floor, among other acts of aggression on the space itself. It was meant (I gathered) to act as a metaphor for sexual oppression or gender issues. The artist was sure the gallerist had pulled the plug on him in an act of censorship. And I thought: No, the gallerist didn’t want to deal with six weeks of off-gassing fumes, and then extensive and expensive clean up.

The tradition of artists attacking the very architecture that houses their work feels as old as the gallery itself, though it’s something that picked up steam in the mid-to-late part of the last century as conceptual and performance art became mainstays on the international scene. There are really two ways an artist can assault an art space—be it museum or non-profit, gallery, or collector’s house—and there are by my count about four common reasons for doing it. Some are better than others.

The first way artists attack spaces is one I won’t spend much time on here, because there are countless examples of it everywhere all the time, and because it’s not an artist-versus-architecture issue. It’s rather an artist-versus-the gallery staff/viewer issue, i.e.: noise or smell or light pollution that has to be endured by staff for the run of the show, and viewers upon arrival. In this version of artist-made passive aggression, there’s no permanent damage to the space itself. Strobe lights, loud music, rotting food, and body fluids abound. It can work, or irritate. It can be very high maintenance.

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (12 Horses), originally from 1969, restaged at Gavin Brown’s space in NY earlier this year.

The dreamiest version of this, though, is Jannis Kounellis’s Untitled (12 Horses) from 1969, which gets restaged every once in a while. While running Fort Worth Contemporary Arts a few years ago, I asked my gallery committee if we could try to get permission to do 12 Horses in the space. They said no.

But horse shit smells great.

The second type of attack, which interests me more here, is the kind of severe damage to the gallery space that requires a serious budget and expertise to correct. One major recent example of this would be Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth, her 2007 installation for which she created a 500+ foot-long, earthquake-like crack right down the middle of the concrete floor of Tate Modern’s massive Turbine Hall. People tripped into it a lot, reportedly, though that seems absurd. The crack wasn’t subtle. I can’t imagine how much it cost to return the floor to its formerly smooth self, and I heard that the floor was indeed not fully restored. I wish I didn’t get worked up over this but I do.

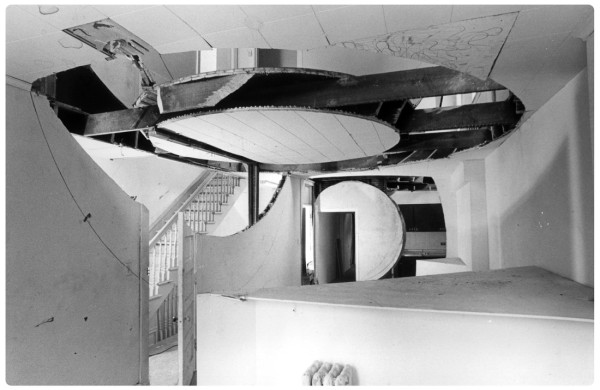

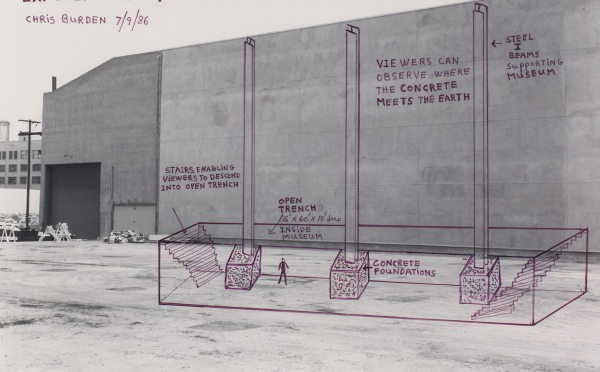

A second notable recent example is also from 2007, when Urs Fischer jackhammered out the entire floor of Gavin Brown’s New York gallery and created an eight-foot deep trench people could climb around in. It was dramatic. It reportedly cost Brown about $250,000, which means today it would cost a lot more. We don’t worry about Brown’s money. On that note: Another good example was from 1986, when Chris Burden made Exposing the Foundation of the Museum at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, for which he did just that. Then of course in 1969 Robert Barry did Closed Gallery, for which the LA gallery was closed for the duration of the show: The ultimate negation of the architectural space.

Here are the reasons artists hurt galleries.

1) It’s short-hand for ‘radical.’ This is Art Student 101 here. Attacking the very space that symbolizes the capitalist impulse that supports the art market’s infrastructure is a big, elementary Fuck You to the system, man. Often what you really see in this case is a gallery obliging the artist by building a false wall for the artist to gleefully saw through while his pals cheer him on.

2) Artists and architects don’t always like each other—a lot of architect-designed art spaces are hostile to art—and since artists get to the space last, they want the last laugh. Actually, a late, great artist in this vein would be Gordon Matta-Clark, who trained as an architect before he started cutting into existing buildings. Most of the structures he mutated were empty and on the fringes of any scene, though once he used an air rifle to blast out the windows of a gallery. And small interventions can be surprisingly effective and destructive. There’s nothing fast or easy about installing Charles Ray’s Spinning Spot. I’ve done it. The motor behind it is big and testy. The patch job afterward is fussy; it’s better to just replace the whole wall.

3) Artists’ own studios where they create work are often abject, plastic spaces for profound investigation, and what artists make isn’t limited by politeness about the space itself. Transferring art from this setting to a clean white cube can, in the artist’s mind, potentially destroy some inherent integrity in the work. Making the clean white cube less precious via roughing it up takes the work back home.

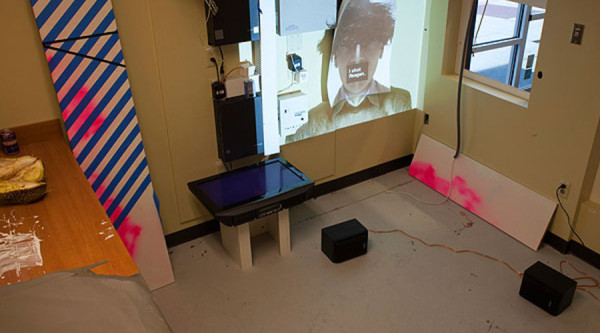

4). Opportunity. Sometimes the creation is in the destruction. This more often happens in off-site spaces. In 2010 I co-curated a show with Thomas Feulmer called Modern Ruin, for which we invited artists to come in and have their way with a government-seized, brand-new bank building in Dallas. A few examples of passive-agressive and downright aggressive gestures included intentional water damage, axed-apart fixtures, carved-up carpet, resculpted window treatments, an opened durian fruit, etc. It was generally clever, and the formerly spiffy, tacky purple interior was rendered unusable for any future tenant.

Likewise, there are about two reasons a curator, gallerist or collector would agree to having an artist damage their space, and two more why they wouldn’t.

1) I think galleries and curators and collectors who love art can feel as stifled by the conservatism of the so-called system as the artists they admire. Every once in a while, money permitting, they like to challenge their own comfort levels and remind themselves why they got into this field to begin with. Destruction is exciting. It feels like trouble. An artist with a sledgehammer wakes you up.

2) The artist is more powerful than the people who run the space, so the people who run the space can’t say no.

And, as a gallerist or curator: why not go along with it?

1) They seriously can’t afford to.

2) The proposed destruction isn’t part of a strong enough idea to justify the expense.

My guess is that as two trends continue to build—which are that real estate is getting more expensive just about everywhere, and art is getting more conservative and sellable—that the physical desecration of a gallery or museum space will be an increasingly rare sight. I don’t know if this is generally fine, since the trend has played itself out, or if there’s something truly lost when the power of money snuffs out an artist’s primal impulse or ability to create something via destruction. I do know that nine times out of ten, if a gallerist refuses to go along with an artist’s grand scheme to tear up the space, it’s not censorship. It’s practicality.

5 comments

“there are about two reasons a curator, gallerist or collector would agree to having an artist damage their space, and two more why they wouldn’t.”

I think there is a third one. It’s related to but distinct from your second reason. Letting an artist rip up your gallery bestows cultural capital on the gallery. It says, here is an institution that will take artistic risks, even to the point of letting itself be physically damaged, for art. It sends a signal to collectors and patrons that your gallery is a cutting edge institution.

I read you ofrenda and I love You weekly commentaries on “go se some art”, specially, your facial expressions. Now, before I go on with my commentary, could you define a gallery?

annoying – you know what a gallery is.

Robert, in agreement and additionally, it also signifies they are successful, signaling “it’s smart to buy here.” One has to sell art in the high figures to justify a $250,000 gallery show. It further shows art sells out of the back, not just the front, which is also a strong market statement. I’m ambivalent to that being good or bad, just think it is so.

Am I the only one who who thrills a little bit at the thought of you installing Spinning Spot? How cooooool. I so want to know how it’s done.