“Most people don’t know how they’re gonna feel from one moment to the next. But a dope fiend has a pretty good idea. All you gotta do is look at the labels on the little bottles.” So says Bob, the protagonist in the 1989 film, Drugstore Cowboy. Later in the movie, he’ll open the door, stoned, to the glare of Gentry, the police detective who’s always on his ass, but all Bob sees are the dozens of little dots on Gentry’s tie. As did we all in the theatre looking at the close-up of that tie sixteen feet tall.

I got a glimpse of something else that year. And it has kept getting bigger: the art of Jesse Amado. 1989 marks the first time I ever laid eyes on his work, at Laguna Gloria in Austin. It was a wall-mounted rubber gesture, a simple statement of composure: look what is available to your senses.

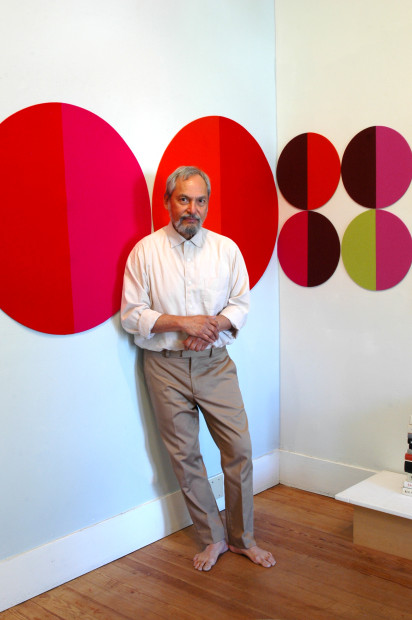

Jesse Amado calls on many forms and precedents for his current show, 30 Day RX, at Ruiz-Healy Art in San Antonio — Pop art, Minimalism, Color Field painting, Conceptual art—as well as his recent experiences with illness and treatment. Half-moon shaped units of thick, multi-hued, virgin wool felt are attached to the wall with tailor’s pins, forming circular images which are simultaneously depictions of pills and non-representational. Either way they are gorgeous, and they go back and forth; you don’t have to choose.

In addition to the broad-stroke art historical relationships, there are some specific points of reference related to the concept of images that represent without representing. Peter Halley’s conduits—abstract paintings indicative of the ducts and corridors of control and conductivity; Fred Tomaselli’s early works in which he sealed pharmaceuticals, cannabis leaves and other mind-bending materials in resin, rendering them viewable but unreachable; Frank Stella’s Moby Dick paintings of the late eighties and nineties, in which the whale is pursued but not apprehended; film-maker Patrick Keillor’s character Robinson, who in the films can be followed but never located.

The largest of Amado’s arrangements in 30 Day RX is two horizontal rows of 36-inch circular discs, with one row of six above the other of seven. Each two-tone circle is split by the line familiar from pharmaceuticals, that straight line that divides the circle in half as on an aspirin tablet. These diameter lines are oriented vertically, and fix the viewer in his or her own body in concert with the upright. Were they set horizontally, the rows would then read as landscapes, each with its own horizon, but linked into a single vista. The vertical axes also imply singularity, numbering, and accumulation—the regimen of medication and the obsession of addiction. This choice of vertical over horizontal is an important one, and symptomatic of the playful rigor that is Amado’s daily way. (He even makes his bed differently each day, playing with the materials of bedding and the variables possible within a closed set of circumstances, the casual intentionality of a person who is an artist all day long.)

The largest of Amado’s arrangements in 30 Day RX is two horizontal rows of 36-inch circular discs, with one row of six above the other of seven. Each two-tone circle is split by the line familiar from pharmaceuticals, that straight line that divides the circle in half as on an aspirin tablet. These diameter lines are oriented vertically, and fix the viewer in his or her own body in concert with the upright. Were they set horizontally, the rows would then read as landscapes, each with its own horizon, but linked into a single vista. The vertical axes also imply singularity, numbering, and accumulation—the regimen of medication and the obsession of addiction. This choice of vertical over horizontal is an important one, and symptomatic of the playful rigor that is Amado’s daily way. (He even makes his bed differently each day, playing with the materials of bedding and the variables possible within a closed set of circumstances, the casual intentionality of a person who is an artist all day long.)

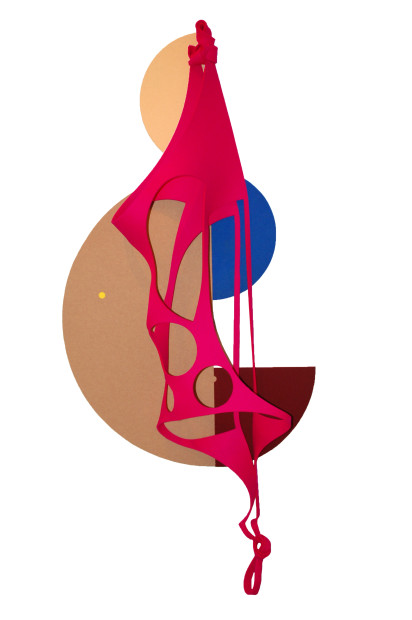

The portion of white wall visible between the circles corresponds in shape to several pieces in the show titled Consequences, each made up from the scraps of felt that occur when a series of circles is cut from a rectangle. Aptly titled, these pieces are the byproduct of sequence, just as is the negative space created by the rows on the wall. It makes no difference if the sequence is a row of felt circles or a series of pills, either way there are consequences, whether visual or vital. These multi-colored tangles hang here and there on the walls of the gallery, strung-out length-wise to the floor in inevitable response to gravity.

Patty Ortiz, author of the essay in the catalog that accompanies the show, calls them “bad trips,” but even though they tumble, she doesn’t mean they are downers. They have their own grace – the dignity of the damaged. As chaotic as they appear they are actually made by artfully knotting and carefully draping one scrap over the other repeatedly, with the subsequent dangles caught in thoughtful interplay.

The bright colors of the several dozen felt discs in the exhibition and their abundant combinations suggest corporate logos, not to mention Pharma-candy’s marketing techniques, and bring thoughts of the free medicine of the earth held hostage to capital. This association is not surprising in context: Amado’s mind-set is inclusive and inquisitive. In conversation, he’s likely to mention the training program of the French Foreign Legion as an anti-depressant, or the fact that traces of Prozac have been found in Colorado fish.

He cites William Morris of the late nineteenth and early-twentieth century Arts and Crafts movement as an influence upon his endless play with materials – somewhat ironic given the industrial nature of many the materials he chooses to work with. But that’s life in the age of post-Fin de siècle idealism.

The Morris connection makes even more sense in light of Amado’s tendency to live in his art. 30 Day RX isn’t just about his diagnosis of cancer, medications and the aftermath of healing; his work has recovered even if he says he took a break from making it. But his involvement with the material of living and his reflections on that have never ceased.

Lately, he’s covered part of the floor of his house with more of the same felt because he likes to walk on it bare-footed. A version of this walk is in the gallery too. Tablet Rug #1, a rectangular section of felt on the floor, with its interior cut circles un-removed and still bound by consequences, is surmounted with two Adidas shoes, which are simple, black, and adorned with these words: Arts longa, vita brevis.

30 Day RX opened April 30 and runs through June 6, about a week longer than the thirty-day cycle. If you wait until the last week, you’ll have to go cold turkey.

Ruiz-Healy Art, 201-A E Olmos Dr, San Antonio, TX 78212, (210) 804-2219

Hills Snyder is an artist, musician and writer. Find out more about him here.

1 comment

Thank you Jesse and Hills! Great work Great read! Onward through the fog! your friend Ken