(Note: This is the sixth installment in a series of stories published in conjunction with the traveling project ‘Altered States’ which opened November 2016 and is still on the move. For Part One, go here. For Part Two, go here. For Part Three, go here. For Part Four, go here, and for Part Five, go here.)

Day Six

The wind-ridden ride left me exhilarated but a bit out of it, so I crashed as soon as I could find a piece of common ground. I was just hoping for something cozy, non-partisan, conveniently atop a healthy slab of archetypal substrate. Toward this end I started to wander. I had touched down in the middle of a circular plowed field, east of Devils Tower, close to Highway 24, in Northeastern Wyoming. Figured I could find some pine shelter within a mile or so, so I parked the truck parallel to the road and walked toward the tower, which I knew to be surrounded by trees.

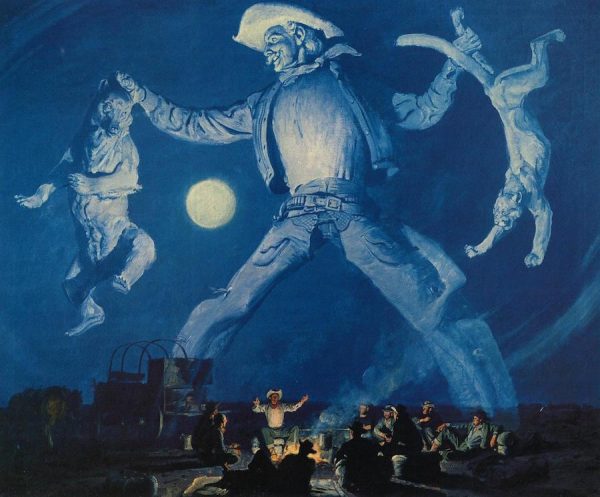

Don’t remember lying down, but hours later and awake, I felt the urge to roll on the ground. So crossing my arms over my chest I threw my right shoulder to my left, doing several revolutions through the six-inch grass, laughing. When I sat up my feet were at the edge of a burnt-out campfire, but when I leaned back again my head was cradled in a pine needle nest right at the base of Devils Tower, which from my point of view was upside down, not unlike so much else in the current reality of record. This spatial distortion, fed by free rolling and a sudden Pecos Bill-style compression, landed me book-ended by a campfire and a mountain, as if I were a conjunction in some epic sentence about the west.

Among first nations, this pushed up, igneous formation is known as Bears Tipi by the Arapahoe; Bears Lodge by the Cheyenne, Crow, and Lakota; and Tree Rock by the Kiowa. It only became known as Devils Tower in recent history (1875), when the Headwesters who came upon it could not figure out how to maneuver their wagons around it. Some thought to the north, others to the south. In the end no choice was made and the pioneer party moved into a penthouse on the top floor, 850 feet above the wagon track. Hence the name Devils Tower. It is thought by some to be the thumb of Satan himself, hitchhiking straight from hell. I can see it. According to Vetruvian proportions his head would probably poke out right about Kanopolis, Kansas, but for now it’s just the right thumb, held high like the Liberty torch. I opted not to check it out, but I’m told the tower’s top floor features a bar that has a gigantic window in the shape of a thumbnail.

There is precedent for explorers and settlers of the new world, when encountering hazard, to rename native sites perditiously. Witness El Purgatorio, a small mountain in the Lambayeque Valley, near Túcume Peru, otherwise known by the more flowing La Raya; and in Mexico, the Tarahumara-named Valley of The Erect Penises, ominously renamed Valley of The Monks.

“Hell is full of mountains,” says Stephen Meek, part of a damnation tripod (bears, Indians) his tongue lashes together in Kelly Reichert’s film Meek’s Cutoff, storied around an Oregon wagon train incident from 1845. Maybe the real Stephen Meek didn’t say this, but if not, somebody on the other side of the mountain did. And then there is Purgatory Mountain in North Carolina, so named in the 1860s, and said to be haunted by the slain hunter of Civil War draft resistors, who was trapped by his 22 captive pacifist Quaker boys and hanged with rope they’d formerly been tied with.

But, in the present, I’m awake and unscarred and looking at this upside down, wedge-shaped butte, 867 feet tall — it’s a gigantic inverted keystone.

A keystone is one of those elemental structures destined to come into being. It’s like the hub of a wheel or the stigma of a flower, the third eye of architecture. The top and final stone placed in an arch that creates the tension that keeps all the other stones in place. Just as windows are wounds, the passages through which light accrues, the keystone is a ray of inward perception and outward influence.

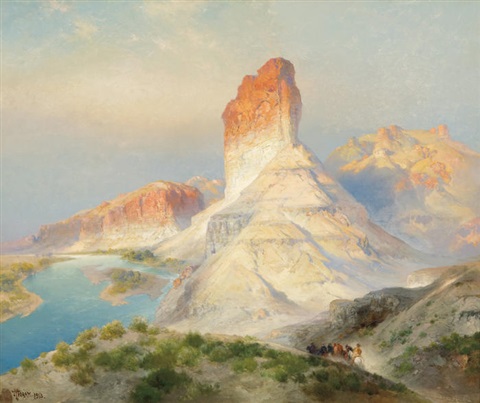

I’m feeling good, humble and small like a figure in a Thomas Moran painting, but I’m suddenly hungry for mashed potatoes. Consequently, I’m reminded of the folk song in which the singer tells of a time he “can recall, seen it in a picture hanging on your wall” and then proceeds to step into the painting, where “the color is better, but the space is tight.” I want to keep this feeling of comfortable insignificance but throw off the feeling that comes naturally from being in a truck 1000 feet in the air inside a tornado. It occurs to me I could have landed on top of the tower, but I’m down here and ready to go, so shaking some ants out of my hair, I make my way back to the truck, determined to drive on.

I’d been in these parts before, 40-plus years ago. Back then I walked all the way around Devils Tower alone without seeing a soul. More than once, with friends too; even crashed there one night in a van — all you could hear was the moon rising. These days the parking lot is full, though there are paths less traveled right around there too. And some spaces still sacred may be found.

Since I was in the neighborhood, I turned north toward Miles City, in southeastern Montana, where I lived for two years in the mid ’80s. I’d been there as an artist-in-the-schools, working within a program that had me with students of all ages in several different schools in a town of about 9000. I’d rented a house right at the convergence of the Tongue and Yellowstone Rivers. It was a great time in my life, so I was pretty excited to see the house again. I’d seen it once since living in it, in the early ’90s. At that time the house was empty and open. Some of the furniture I’d abandoned years before was still there. An empty Shiner Bock case that had been brought to me by a friend from Texas remained in the mudroom and a red shoestring that my five-year old son had looped and knotted on the front door knob remained tied. The massive hollyhock patch that I loved was busting its color on the east side of the house, but that was 25 years ago, so as an unaware Rip Van Winkle I walked the bank of the Yellowstone from the art center where my studio had been to the broken stile that crossed a pasture fence into what used to be my yard.

A lot can happen in two and half decades. We’re all consciously and unconsciously pulling various realities into being. No one gets to get it completely right, so we struggle with a unity that comes and goes, toiling solemnly and tinkering joyfully on a machine that nobody can recall inventing. The relentless presence of the task can at times put you to sleep, and The Sandman waits for us all. You could wake up kicked in the gut, your lights knocked out, with a silly orange face spray-painted on your forehead.

The house was last occupied in 2002 if the calendar I found inside was an indication. Every floor was covered in inches-thick debris — magazines, laundry, food containers, a novel titled No Time To Look Back, cardboard boxes a quarter full with more of the same trash. Door and window openings gaped with yawns and blank stares. A harvest-gold upholstered chair that I’d left there in 1987 and seen there years later, right where I’d left it, was now in the middle of the kitchen, maybe from someone standing in it to remove a light bulb from the ceiling fixture on the night that they’d left in a hurry. It was the type of chair that swiveled — I can feel the instability under the feet of whoever pulled that bulb and the uncertainty they surely felt for whatever was coming next for them. For now it was a lackadaisical welcome back, cradling a pale blue child’s Croc, a plastic olive oil bottle, and an empty prescription container; not really inviting me to sit. Walked back along the river to my truck and drove into town so I could count once again the 100 street lamps of Main Street before heading south. I’d be back in Wyoming in two hours.

The earth in Northeastern Wyoming is a velvety red pink. Some of these pine-lined back roads, tongue red and snaking through fuzzy green, my god! Even some of the paved roads are pink, as if some local dirt got into the asphalt. I’m now moving southeast, toward Keystone, South Dakota, riding on a pink two-lane bisected by two parallel yellow lines, with reflectors attached to the center line every couple of car lengths shining like mother of pearl. The road undulates but eventually smoothes out, flat as an ironing board. An immaculate macramé chicken that I found in the debris in my used-to-be yard looks at me from the dashboard as I drive out from under the restless triad that seeing the old house trapped me in and I’m feeling resolved — loose and inquisitive, furtively fun, flying like a chimeric hermeneut down a giant pink-with-yellow-piping snap shirt, fully ready to be in heaven a half hour before the devil knows I’m dead.

To be continued… .

Hills Snyder’s ‘Altered States,’ a travelogue and traveling exhibition of drawings from the road, continues: Part Seven of the travelogue will appear in Glasstire on July 31, 2019. Part Four of the traveling show opens at Ruiz-Healy Art in San Antonio on November 14, 2018 and continues through January 19, 2019.

1 comment

Great Hills . I love it. Thanks Ken