The videos curated by Sally Frater in There is no archive in which nothing gets lost at the Glassel School of Art speak my language: repetitive gestures performed by women across time. In this post, I describe the videos through my eyes, then I interview Frater about her process. You can hear more from her at her curatorial talk this Wednesday at 4pm in the gallery.

Lorna Simpson

“Corridor”

(2003)

Double-projection video installation, video transferred to DVD

13 min., 45 sec.

Corridor by Lorna Simpson shows two scenes simultaneously, side by side. The same figure (Wangechi Mutu) plays two women. One is a house servant from 1860 when the Civil War began, and one a house wife from 1960 when the Civil Rights Act passed. The camera is an almost voyeuristic presence in the domestic spaces of these women as they pursue their daily routines in parallel spaces with parallel rituals. These are their moments of preparation, their chores of self-maintenance and long stares out of reflective windows. The exteriors of their homes are shown. It’s winter and the women seem equally frozen, waiting for the presence of someone who does not arrive on the scene. There is no local audio, but occasionally dissonant sounds from a piano merge with sounds spilling from the other galleries. [1]

Wangechi Mutu

“Cutting”

(2004)

DVD, single channel

5 min. 45 sec., loop

Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter, Los Angeles Projects and Sikkema Jenkins & Co

Wangechi Mutu’s Cutting frames the artist, machete in hand, on a desert hill at a lavender dusk. Initially, her apron is a bright diamond of red, but her distinct features dim into a backlit silhouette as the sun sets. Increasingly frantic, she hacks at a trunk of dead, possibly petrified wood. Her actions are slowed, but the machete’s metallic echo reverberates off the wood. The wind gusts and dry earth crunches subtly under her feet. The machete sticks in the wood, and Mutu steps away, massaging her lower back. The scene fades in and out. As you move down the hall, you hear the sounds of her chore repeating over and over.

Sonia Boyce in collaboration with Ain Bailey

“Oh Adelaide”

(2010)

Single screen video with sound

7 min., 12 sec.

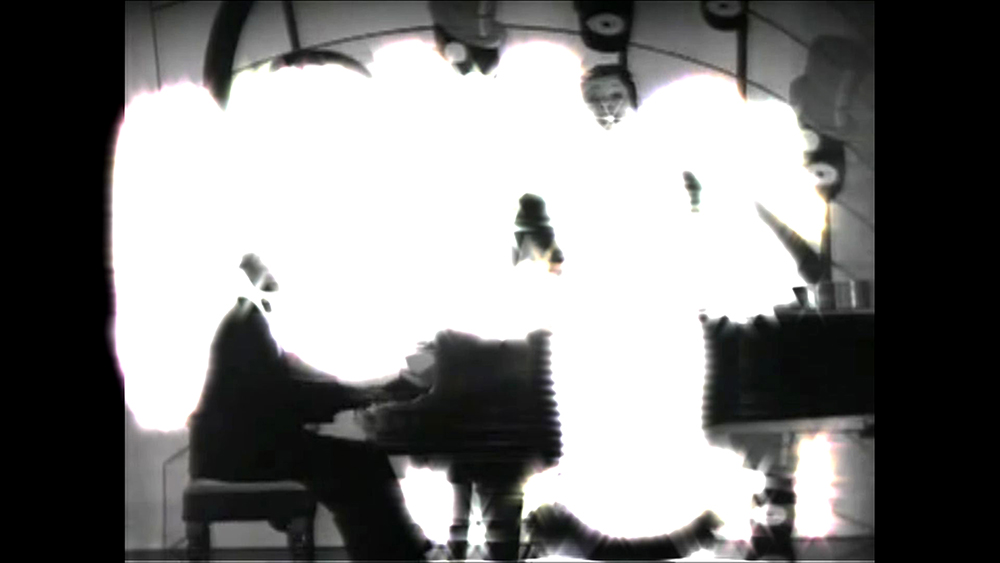

Sonia Boyce collaborated with Ain Bailey to create Oh Adelaide. Shown in a curtained black box room, the video shows famed jazz singer Adelaide Hall performing, obscured by the glare of a spotlight. You see her face and her dancing feet in split seconds between the smothering overexposure. The audio distorts into growls; just a few haunting moments of Hall’s bird-like song are audible. Hall sings the first wordless jazz vocal, “Creole Love Call,” performed at the Cotton Club in Harlem in the 1920s. It’s hard to disengage from the relentless sparkle in Boyce and Bailey’s collaboration.

Carrie Schneider: How and why did you choose the works in There is no archive in which nothing gets lost?

Sally Frater: For a while, I had been thinking that I wanted to curate an exhibition of time-based works that engaged with elements of performativity and notions of history. There were aspects of film and video that I was interested in investigating, as well as the relationship to performance, narrative and representation. Originally I had envisioned that the exhibition would be more extensive, in that it would include the work of a greater number of artists and would take place in another venue. In a sense, this is a microcosm of the show that I had originally conceived of, yet I am extremely happy with what has resulted and don’t know if it is necessary to revisit this as a larger exhibition. The opportunity to stage an exhibition at Glassell arose, and the three videos that are included in the exhibition work well with the physical challenges of the space and resonate with each other.

CS: I really agree, one thing that strikes me is how concise and cohered the show is. The dissonant sound work, the slowed, repetitive gestures and absent/abstract antagonists heighten this feeling. Mutu is the performer in both Corridor and Cutting. Did you intend to curate the works in a way that makes it feel like these figures could move from one scene, time, or video to the next?

SF: Although I would agree that there are similarities shared between certain works in the exhibition, such as the altered sound and imagery in both Cutting and Oh Adelaide, and the historic specificity of Corridor and Oh Adelaide (i.e. both works can be categorized as “period” pieces), I understand the work as three distinctly separate works, in spite of the fact that Mutu appears in two of three pieces. I think that the works deal with different episodes in history and present different narratives … I don’t feel that there is necessarily a visual or aesthetic continuity between the pieces, or that there is a thematic one. I would hesitate to frame the works in the manner that you have suggested because I think that there is a tendency to do this with certain artists, and it results in the subtleties of their work being overlooked and ultimately does a disservice to it. I selected each of the videos mainly because I am a huge fan of each piece. I am particularly enraptured by the aesthetics of Corridor and Oh Adelaide. Cutting I find captivating due to its deceptive simplicity: It seems straightforward, but it is actually quite a dense, multilayered work. Though each piece differs in terms of subject matter and theme, they each share a common trait of bringing forth a history that is overlooked, or a perspective that is not often considered, hence the title. I am not necessarily interested in examining “the archive” per se with this exhibition, but I did intend to position each work as an archive that contains a specific history and/or narrative. Having stated that, however, my main interest in each work was the manner in which each individually proposes a filmic intersection of site, memory, performance, narrative and history that is specific to each work.

CS: Have you written about or curated works by these artists previously?

SF: I co-curated an exhibition entitled 28 Days earlier this year that included works by both Sonia Boyce and Wangechi Mutu. This is my first time curating a work by Lorna Simpson, though I have been following her work since encountering it as an undergraduate student in photography. I have not worked with Ain Bailey prior to this exhibition. I have written about both Mutu and Simpson’s work prior to this show.

CS: How do your writing and curating practices overlap?

SF: When I write in relation to an exhibition that I’ve curated, it is usually with the aim of producing something that is either explanatory or that further elucidates specific aspects of themes explored in an exhibition. It’s interesting because I don’t usually approach writing with the goal of producing something that unfolds in a manner that is analogous to the work being shown, which I suppose could be an interesting exercise. For me, writing is often the final step in the curatorial process and I feel that it is something that is often useful in terms of articulating aspects of an exhibition that I may be grasping intuitively or subconsciously, but haven’t fully brought to the fore. I have a friend who is an artist who once told me that often when she produces a work, she is not entirely sure of what her motivation is, but that it becomes clearer to her after the fact. While I wouldn’t exactly equate my curatorial process to her artistic one, I find that writing occasionally does illuminate certain aspects of an exhibition to me after I have finished the act of writing.

CS: Are you the first Critic-in-Residence at the Core Program to curate? I would love to see more.

I am not the first Critic-in-Residence in the Core Program to curate an exhibition. I don’t know much about past curatorial projects by Core fellows, but I know that I am not the first. Jennie King, who was the recent Interim Public Art Director at Project Row Houses, is a former Core fellow and she curated a project which I believe was installed in the Cullen Sculpture Garden at Glassell and sounds quite interesting, but apart from that I am not too familiar with past Core curatorial projects.

There is no archive in which nothing gets lost

Glassell School of Art

Curatorial Talk 4 p.m., Wednesday, Novemember 7, 2012

[1] Since the time of my visit I’ve been informed that a saxophone track was added.

________

Carrie Schneider is a Houston-based conceptual artist.