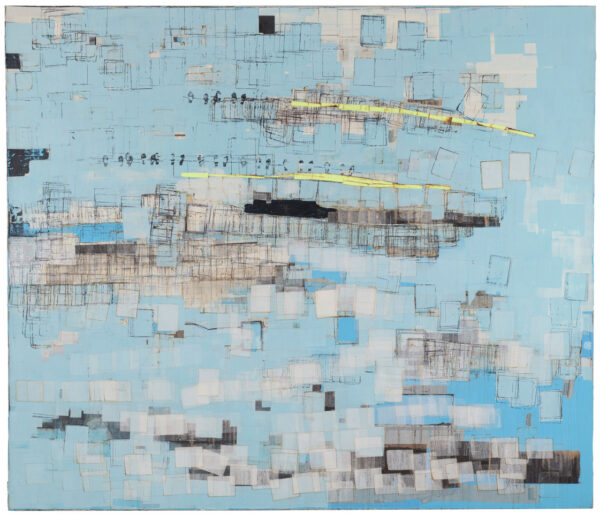

Mark Bradford, “Same ‘Ol Pimp,” 2002, mixed media on canvas, 72 x 84 inches, Collection of Barbara and Michael Gamson (photo: © Paul Hester/Hester + Hardaway Photographers)

An action-packed exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin spotlights nearly 100 works from 38 artists whose day jobs not only informed their art, but became their art. The lineup includes both emerging and established figures who moonlighted, side hustled — and even went corporate — all in a bid to pay the bills and grace the walls.

Organized by the Blanton’s former curator of modern and contemporary art, Veronica Roberts, and former curatorial assistant Lynne Maphies, the wide-ranging exhibition has been years in the making. Though Roberts knew from the outset certain artists would be included — former Condé Nast head designer turned conceptual collagist Barbara Kruger, for instance — others came through word of mouth from artist friends and fellow curators who shared numerous stories about rather intriguing, and often unassuming, paths to success.

Tishan Hsu, “Portrait,” 1982, oil stick, enamel, acrylic, and vinyl cement compound on wood, 57 x 87 x 6 inches, Courtesy the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York (photo: © 2022 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

“The criteria had to be not that someone had a day job — every American artist has a day job — it was that the day job had a real influence on their practice and shaped their work in some pivotal way,” said Roberts at the show’s press preview.

Day Jobs begins with an installation titled Piloto (Pilot) (2022) by Puerto Rican sculptor-inventor Manuel Alejandro Rodríguez-Delgado, showcasing an autobiographic, futuristic space pack created during his recent residency in Galveston. This is the first time Delgado’s work has appeared in a major museum exhibition and it speaks, quite literally, to the work it took to get here. After graduating from Escuela de Artes Plásticas in San Juan, the artist completed an MFA at the Art Institute of Chicago, taking a job as a crate maker to offset student costs. (A pair of crates, shown adjacent to the sculpture, were custom-made by Delgado to transport the work itself.) His battery-operated, thermo-controlled pack (complete with pandemic-proof breathing apparatus) contains a notebook brimming with notes — ideas for future works — years in the making, ready for takeoff.

Farther into the gallery, we see works by Robert Ryman, Dan Flavin, and Sol LeWitt — all of them had jobs early in life at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) — with Flavin’s fluorescent “monument” for V. Tatlin (1969), a sort of spire-less skyscraper, soaking up much of the attention. Flavin, who worked as an elevator attendant at the museum, was allegedly fired for being a motormouth. Ryman, a jazz musician and security guard, was so taken with what he saw on the walls that he put down his saxophone and took up painting instead.

Howardena Pindell, “Autobiography: Japan (Mountain Reflection),” 1982-1983, acrylic, punched and cut paper, and threat on cut and sewn unstretched canvas, overall 107 x 106 3/4 inches, Collection of Timothy C. Headington. Photo: Barbara Purcell.

There is also an abstract work by painter (and MoMA staffer) Howardena Pindell, who trained as an oil painter at Yale but struggled to find success in the medium. So she used office supplies to hole-punch her way out of a long-time position at the museum. (Look closely at her work and you will see a cosmos of paper dots.) Later in the exhibition, a stainless steel bust of Louis XIV by Jeff Koons shines like a beacon of pop. Koons, who was a commodities broker before he made sculptures, worked at the museum’s membership desk when he first moved to New York.

Though MoMA, as a right of passage, proves somewhat legendary in Day Jobs, the exhibition expands into six separate categories: “Art World,” “Service Industry,” “Media and Advertising,” “Fashion and Design,” “Caregivers,” and “Finance, Technology, and Law.” Certain jobs (like working at a museum!) might seem like the obvious choice for an aspiring artist, but as this show reveals, each industry spurred just the right epiphany for each artist and their practice — be it through materials, execution, or just plain old experience.

Take Allan McCollum, a former airline food preparer, whose massive wall-sized installation, Surrogates (1983-1985), consists of 200 tray-like frames of various sizes and colors — mass-produced yet hand-painted — speaking to the commodification and intrinsic value of any given art object. And Tom Kiefer, a fine arts photographer who worked part-time as a janitor at a U.S. Customs and Border Protection processing facility in Arizona, whose photographs of artfully arranged objects confiscated from migrants are an aerial display of ethereal beauty.

Violette Bule, “Homage to Johnny,” 2015, silverware, steel grate, and magnets, (approximate) 48 1/2 x 65 x 15 inches, Collection of the artist. Photo: Barbara Purcell.

There is also Venezuelan-born Violette Bule, who spent time working in New York City restaurants. Her sculpture, Homage to Johnny (2015), showcases a metal grate, like the ones flopped open on the city’s sidewalks that lead down into the dungeons of its eateries. Homage opens like a religious triptych; a dense concentration of forks, held together by strong magnets, which acknowledge the weight that a worker like Johnny, paid under the table, under the streets of New York, must wash away, one by one, in order to finish each day.

Not to mention Bronx native Fred Wilson, who, as a kid, spent so much time in the city’s museums, he soon found himself working in them. Wilson’s installation Grey Area (Brown version) (1993) features five busts of the Ancient Egyptian queen Nefertiti, each a different shade of brown, ascending from light to dark, calling colorism, beauty, and provenance into question all at once. (The original is in a museum, not in Cairo, but Berlin.)

Two abstract paintings by Mark Bradford incorporate end papers and hair dye — product essentials he used for years while working in his mother’s Black beauty shop in South Los Angeles. Tishan Hsu’s Portrait (1982) speaks to the ways in which technology cleaves us from our own bodies; at the time, Hsu worked the night shift as a word processor (pre-computers) at a law firm in Lower Manhattan. Jeffrey Gibson’s People Like Us (2018) depicts a ritual garment worn by Native Americans to ward off harm, and floats outstretched in the space like a dazzling window display. Gibson, who is of both Choctaw and Cherokee descent, possessed such talent as a visual merchandiser for IKEA; the company had wanted him to transfer to their headquarters in Sweden.

My favorite example of an artist’s unending quest for work-life balance comes from the British-born, Pittsburgh-based artist Lenka Clayton. Her zen-like 63 Objects Taken Out of My Son’s Mouth (2011-2012), squares up the viewer on this one simple truth: being an artist is as glamorous as getting through any given day. Clayton, who founded An Artist Residency in Motherhood in her own home, has placed each inedible goody that her son Otto once tried to swallow into a 9 x 7-foot display case as a reminder of the various responsibilities contending with an artist’s inner life, let alone studio life.

Fred Wilson, “Grey Area (Brown version),” 1993, pigment, plaster, and wood, overall: 20 x 84 inches, Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of William K. Jacobs, Jr. bequest of Richard J. Kempe, by exchange 2008.6a-j (photo: © Fred Wilson, courtesy Pace Gallery).

Day Jobs delights in showing us the back of the painting; the slog that gallery goers seldom see. It is as much a tribute to these artists and their stories as to the countless artists who put in the work, every day, whose work may never be seen in the light of day. At last, the Hollywood image of a tortured soul, holed up in some studio, has been shattered like a Koons balloon: artists are people just like us.

Day Jobs runs through July 23, 2023 at the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin.