380 East is my current favorite road into Texas from New Mexico. The connection to it is less than forty miles from where I live in Magdalena, west of Socorro. I’m on my way to drive a long loop through the Texas Panhandle and back into New Mexico, mostly to see artist-run-spaces and artists. I will miss more people than I find, but there will be connection, memory, and overlap. Among the very specific individuals that I meet, something may arise that connects them all.

Driving all these same roads so many times, seeing things fall apart and eventually disappear, hearing so many songs written on and about these roads, movies that morph linear time into other shapes — there is no question that road trip peripheries will ensue. This is a personal story, mixing what I’m finding with what I’m losing and rolling up on things that happened or that might happen.

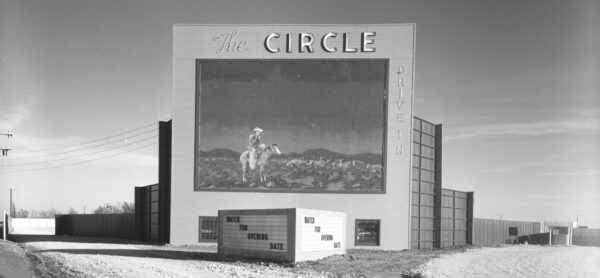

Circle Drive-in, Lubbock, Texas, 1949 — 1980, Courtesy Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library Texas Tech University.

Twenty miles west of Carrizozo, after a curvy road through low sandy cedar hills, the road drops into a wide basin marking the boundary of the Carrizozo Soil and Water Conservation district. From this point on, Nogal Peak is frequently centered on the route to town.

Monjeau Lookout, Sierra Blanca, and Nogal Peak are connected by the Crest Trail, my go-to path in Lincoln National Forest, but I hold special affection for Nogal. In the seventies, one summer on top — every rock and bush, every blade of grass, every kind of surface was completely coated with ladybugs.

Thousands.

I especially recall the long strands of grass, waving under the weight of so many insects, the lady bugs lined up on a bridge to nowhere for reasons of their own.

Ten years ago, winding my way up Nogal, I found a rusty three-inch lag screw on the ground, reminding me that the palindrome may assert its implications at any moment, anywhere.

Nogal Peak is pyramid-shaped, as seen from due west, but from other points of view those angled slopes appear more acute. You will see it shape-shift, accordion style, if you drive completely around it by connecting 380, 37, 70 and 54, arriving where you began in Carrizozo.

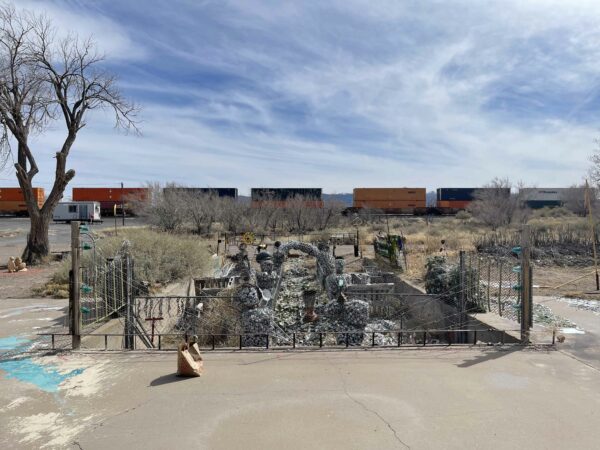

I’m pulling into Carrizozo at noon on a Friday, because on Fridays, the place to be in this small New Mexico town is MoMAZoZo, the corner of the world inhabited by Paula Wilson and Mike Lagg. They call the weekly get together MoMAZoZo Hour, and you are invited to show up and throw some glass.

First thing I see when I pull up to park is a nothing-but-cherry ’64 Buick Skylark, which I take as a good omen. Right away, another good omen walks up in the form of Matthew Midgett. He has a place near Nogal that he calls Followed Dream Ranch. He has a couple of horses and rides every day. He’s had the Skylark since 1971, when he bought it right after high school. It’s a joy to meet him.

MoMAZoZo’s glass recycling is a ritual that invites you to toss bottles at an inverted funnel-shaped metal receptacle which rises out of a sea of glass shards contained within a large concrete pit set into the ground. A ring like a bell is one of the possible rewards for your effort. You might even get a pretty ricochet.

After the bottle toss, visitors are welcome to tour the building and grounds, which they call the Lyric Complex after the long-closed Lyric Theatre, which is attached. The compound occupies an entire block and combines both artist’s work spaces with other spaces that are best described as installation zones that turn dilapidated aspects of the building into material for art. One such space is simply a sandy area on the floor upon which falling debris and roof leaks make marks. Another is a room completely open to the sky which continually changes.

In addition to making these works in which randomness and malleability are the main aspect, Lagg is also an accomplished woodworker and clever inventor. His kinetic sculptures, devices, and gizmos are everywhere in the space and on the grounds.

Wilson’s work spans an ambitious variety of media. This day she is assembling materials for a large piece constructed from small irregularly shaped paintings that are essentially hand-made components for collage. The various works in progress scattered throughout her work space testify to her prolific nature. Her conceptual concerns are equally wide ranging.

They are busy preparing for a July trip to the northeast where Wilson has an ongoing two-person exhibition in Waterville, Maine and a solo project titled Toward the Sky’s Backdoor opening July 15 in Saratoga Springs, New York.

Wilson and Lagg are co-founders, with Warren and Joan Malkerson, of Carrizozo AIR, an artist residency based downtown.

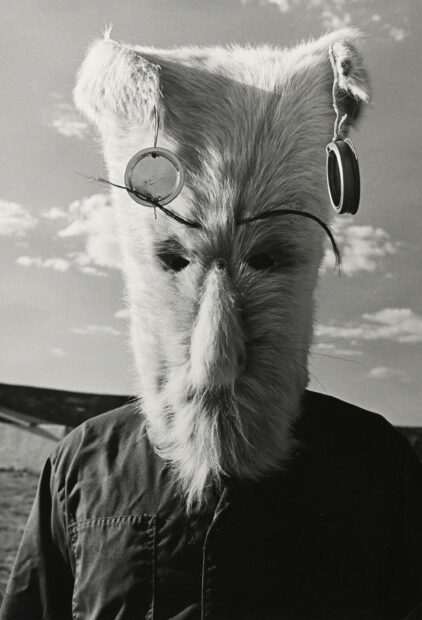

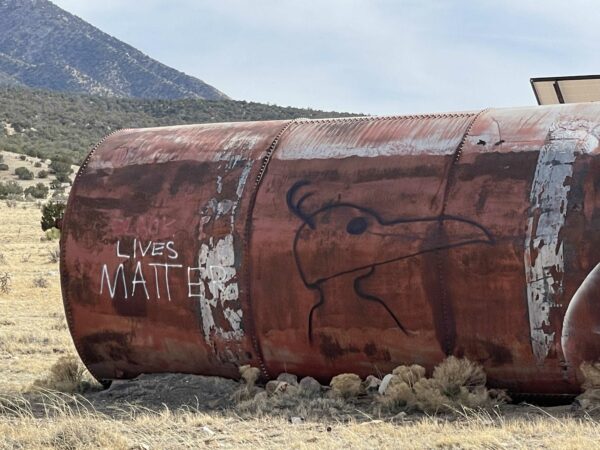

Carrizozo is centrally located in a creative continuum in central New Mexico extending from Roswell to Magdalena, with 380 as the connecting road. Along this highway you might notice an image of a human figure or head and shoulders topped with a bird mask. It could be said to resemble a medieval plague mask, though these images predate Covid by years. You will see them on derelict buildings, water tanks, abandoned RVs, the remains of a concrete bridge, from San Antonio to Capitan; on Tanbark Canyon Road in the Lincoln National Forest; and the one I saw for the first time today as I headed toward The No Scum Allowed Saloon in White Oaks just north of Carrizozo.

The saloon was closed so now I’m on the road toward the Texas border. As I pass through Tatum, I recall the burger place that was once on the north side of the highway. It could have been a Dairy Queen, seemed more homegrown, but it is no longer there. The folks that ran the place in the sixties had a green mid-fifties Chevy, or maybe a Hudson, always parked west of the building. They had a special needs child, a little girl, with no one to look after her during the day, so she stayed in the car while her parents were working. I was twelve the first time I noticed her, with the black soles of her red Mary Janes pressed against the windshield. She had jet black, cropped hair and always seemed occupied with something. Tatum has since been for me a locus of wondering what became of her.

A few miles down the road, almost dark, I pass through Plains, Texas, thinking about a connection held by San Antonio, TX artist, Jeff Wheeler and Santa Fe, NM artist, Paul Milosevich. Years ago, Paul taught art classes at the old courthouse turned community center in Plains. These days Jeff has a similar gig, same town, same courthouse, but here is the interesting part — they have a student in common. She was in Paul’s class thirty years ago and Jeff’s in 2022.

I was hoping to get a shot of the old courthouse, but it’s gone dark and I’m not sure where it is, so I substitute this shot of the Dairy Queen instead. It’s on the north side of the highway, just like the Mom & Pop place in Tatum was, so for me that is an emotional connection.

Crashing with a musician friend in Lubbock. He is currently fascinated with British-Albanian singer Dua Lipa, so we listen to her for a while before swapping a couple of songs and shooting the breeze.

Conversation includes revisiting the day my Coronado High School garage band was practicing Jack and The Beanstalk, a song by The Sparkles, a sixties band from Levelland. We were making good progress learning the song when the only mic we had failed. One of the guitar players valiantly tried to solder the loose wire with a heated fork. It didn’t work, but if memory serves, he had a job for a while on the electrical maintenance crew at Tech a few years later.

I’m not going to supply the context, but another story comes up of a cosmic adventure that took place in the seventies on a porch in the Midwest, prompting my friend to say, “It’s a shame that more congregations aren’t into nitrous.”

Saturday morning, we go for breakfast at the Tech Café at 50th and P, like we always do whenever I come through Lubbock. My first stop after that is the Land Arts of The American West exhibition at the Texas Tech Museum.

Referring to the Land Arts program as a “semester abroad in our own backyard,” participating students and scholars camped for fifty days and traveled 5,522 miles overland visiting artists and seeing land arts monuments while conceiving and creating the work in the exhibition.

The participants in the field research and subsequent exhibition are Ty Cary, Elise Coleman, Macaella Gray, Walker Guinnee, Miranda Klein, Emily Lee, Megan McKenzie, and Zoe Roden.

Ty Cary offers a twenty-one-minute video, Desert Gestures. Narrated by his friend Nick Fortna, whose voice hits the perfect timbre for the project, it is a travelog of vignettes about westward expansion and first contact, presence and particularity of place, haptic histories of early Puebloan cultures, portable architectures of shelter, migratory movements of nomads and refugees, mutable landscapes, desert stillness, and an epic dive into primordial anthropomorphism: I know I’ve forgotten something, but I don’t know what it is, said the earth.

The first story that is told is that of the Donner-Reed Party, which played its part in westward expansion and was famously caught in a cycle of exposure, starvation, and cannibalism.

“In total, just over one half of the party would survive the ordeal and reach the far west. Fueled by the mythos of a western Terra nullius, the colonial imaginary drew the Donner-Reed party to the hinterlands of territory and sensibility, the promise of boundless prosperity on the other side of these borders. An insatiable appetite for land and the sovereignty that would come with it was aroused. And so, when faced with an impasse, such hunger had only itself to consume.”

The Donner-Reed story stands in contrast to the other episodes in the video as the only section about misplacement, as opposed to place, which is the central theme of Cary’s tale. One account of place takes this concern “home” in a rhapsodic meditation on the tent that was Cary’s abode for the field research trips.

The video concludes at the Very Large Array, 25 miles west of Magdalena: “…wandering continues, the world unfurls, to offer itself once again.”

Walker Guinee’s Journey Two maps the duration of each site visit with different sized camp kitchen bowls of the baked enamel variety, familiar items of Americana since the 1870s. The larger the bowl, the longer the stay. The bowls are anchored in a wood platform painted dirt brown, each filled with water, which casts semi-circular reflections on the surrounding walls. A side commentary on the scarcity of water may be embedded in this piece, as the map projected on the walls by the reflections would surely disappear as the water evaporates, unless replenished. The piece also calls to mind the reflecting pools at Machu Picchu, which mirror the sky and were used for astronomical observation.

Other works in the show are various collections, prints, recordings, photographs, documentations, and found materials that chart and diarize the groups’ field research, including Elise Coleman’s Back Woods Trophies, a piece which maneuvers the gap between found objects and ready-mades with newly empty cans shot with bullets and shells the same caliber and gauge as casings found on the ground during the Land Arts field research journeys. Jack Craft, a rancher-turned-artist, provided the ammo and the site for the shooting at his place near Clarendon, northeast of Lubbock. Craft also oversees the Oakes Creek Residency and knows where his water comes from.

The title of another work by Coleman contradicts the image. This is Not an American Flag is a mixed-media piece presenting a black and white likeness of the American Flag, with a green automatic rifle superimposed on it. The title plays on the popular Magritte piece, Ce nais pas une pipe, in which an image of a pipe is indeed not a pipe. And the image of a flag is indeed not a flag, though draining it of red, white, and blue isn’t what makes this so. Any representation is just that. A point being made is that an AR15 should not represent a nation the way a flag is said to do. The image of a weapon, however, may potentially be a weapon, hence the contradiction. The image of an AR15 of any color actually does symbolize the devil’s bargain that America has made with the Second Musket Amendment.

The road from Amarillo to Clarendon is familiar to me. In 1978, I was hired along with a couple of others to deliver some art from Austin, where I was living, to the Amarillo Art Museum, then known as the Amarillo Art Center. It was not your conventional art handler trip — we delivered the work in a horse trailer and dropped some window pane on the way back.

As we neared Clarendon we came upon a startling tableau on the edge of town, which featured two figures, a man and a woman, each holding child-sized fishing rods such that the tips of the rods were downcast in dust that had accumulated in a plastic wading pool. The rest of the set up was populated with various objects, including a couple of rubber ducks that had clearly been floating in the wading pool prior to the evaporation of the water and the subsequent dust. When we got out of the car to take a closer look, a woman came out of the house to greet us and to explain that the installation represented her and her husband. It was a bit eerie, because she spoke as if they had just made it, even though it had obviously been there for years. Her face told the story too — she was very pleased and excited that we had stopped to look at her art. Her name was Nell.

Before leaving the Museum, I commune for a while with Painting No. 2 by Ed Blackburn, which is included in the Centennial show. The painting is based on a film still of Frank Sinatra dancing with Debbie Reynolds in a New York apartment from the 1955 movie, The Tender Trap.

The scene comes from a moment when they dance their way to the door of Charlie’s (Sinatra) apartment to go out, but the dance is actually a subterfuge — it creates the opportunity for Charlie to snatch some revealing notes from the desk as they begin to tango. On the screen they move away from you, but in the viewpoint offered by the painting they face the desk and you in the theater beyond it. The characters are caught in freeze frame in the Blackburn painting, as the specific perspective depicted doesn’t appear in the movie. The image the painting is based on comes from an archive, and as such it carries the melancholy of an attenuated memory. It bears a sweetness.

The film starts with Sinatra strolling toward the camera from a deep distance on a boundless sound stage. The screen is filled with three elements: figure, sound stage, empty space above the stage. Horizon implied. Eventually you see a pair of laughing eyes. There’s no gettin’ out. You’re trapped in a three-dimensional world.

I’m recalling a time with Ed in September ‘94 when we went to Texas Stadium for a Cowboys game that went to six full quarters in order to break a tie. We got out of there at midnight. A few weeks later, Ed gave me some trading cards he’d made featuring Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, and Neil Young.

Texas and the rest of us lost some good people in 2022, including Ed, Jo Carol Pierce, and Frances Colpitt.

BTW, my soundtrack for this road trip has largely been Jo Carol, Longriver, Jake Xerxes Fussell, Garrett T. Capps, Colin Gilmore, and Hayden Pedigo.

My early exposure to the Tech Museum was in the late fifties or early sixties, when it was in Holden Hall in the middle of the Tech campus and featured a panoramic Peter Hurd fresco high on the wall in the rotunda. The mural documents a history of the settler culture that came to be known as Lubbock. Painted in the mid-fifties and known as the Pioneer Mural, it features a campfire scene that might remind you of the painting behind the stage at the Starlight Theatre in Terlingua.

Mid-day I meet up with Hayden Pedigo and his partner and collaborator, L’Hanna Pedigo, at their house in Tech Terrace, the neighborhood where I once sat in my car transfixed outside a small grocery store so I could listen all the way through to a pre-release single off the White Album.

Their place is full of art and the kind of stuff that creative couples tend to accumulate, including L’Hanna’s anniversary gift to Hayden — a framed crochet the size of an album cover made by a friend duplicating a photo of a crochet that is the cover of Harry Nilsson’s The Point; a painting by Amarillo artist Jonathan Phillips marking the day they left Amarillo for Lubbock; and a diorama of Cadillac Ranch made by Hayden’s dad.

Gumby appears at least three times, including two appearances in the music room, which also features Iron Butterfly and Ricky Nelson posters, an image of John Wayne decoupaged to a slice of tree, and a photo of wrestler Terry Funk.

Hayden is extremely happy and excited about his new record and talks about it “destroying” his previous work, saying, “The new record is the music I’ve always wanted to make.”

It is titled The Happiest Times I Ever Ignored, paraphrasing a haunting note written by National Lampoon Co-founder, Doug Kenney, who slipped out of life on a precipice of excess in 1980 at Hanapepe Lookout in Hawaii. The note rattled Hayden when he heard it quoted in a film — he was so shook that he had to title his record from it.

His song Some Kind of Shepherd on his 2021 release, Letting Go, triangulates nicely with a couple of Jorma Kaukonen songs, Embryonic Journey (Jefferson Airplane) and Water Song (Hot Tuna), not to mention a free association to yet another Airplane song that is sung by Kaukonen, Good Shepherd.

The long-tongued liar, gunshot devil, and blood-stained bandit that the song warns of persists in American political culture. Playing the song since the early sixties, Kaukonen interpreted the bloody bandit as the KKK.

Good Shepherd is an early nineteenth century hymn, which by the end of that century had become a gospel-blues standard and by now is a song that has been sung for two hundred years.

Contemplating the long history of the song now gives rise to a longing look down that way, to the west, toward Tatum, or even farther, to Hanapepe Lookout and Molokai, in Hawaii, where another tragic death of a counter-culture figure occurred, in 1997, when Spirit’s Randy California drowned rescuing his twelve-year old son from a rip tide.

Conversation with Hayden inevitably turns to John Fahey. We also get going on Captain Beefheart — an anecdote is told of him picking the blues brain of record collector, radio host, and blues historian Dr. Dimento at an Upper West Side lunch in 1980. The Beatles come up. ZZ Top, Judee Sill, Mick Taylor, The Mothers, garage bands — all musical pools that we have fun diving into, but for Hayden things always come back to the surface with Fahey.

Dr. Dimento, otherwise known as Barry Hansen, bought a copy of Letting Go, delivering some excitement to Hayden in the process, due to the Fahey connection, who was among artists Hansen worked with in the late sixties. In the right place at the right time, he taught Fahey how to make tape loops, lived with Spirit in Topanga Canyon, and introduced Al Wilson to Bob Hite, a key moment in the formation of Canned Heat. Hayden, right now, right where he is, is right where he should be too.

The Happiest Times I Ever Ignored is the sound of rising up and taking a long open 360 degree look into wider and deeper and taller spaces. The video for the song Elsewhere from the new album tells a story that parallels Hayden’s life in some ways, at least so far as his creative persistence is concerned. Smartly story-boarded and directed, well done, sweet, and fun, the video will be released mid-April when the new album is officially announced.

COOPt Research + Projects is a space at 42nd and Boston in Lubbock, run by a collective of artists, writers, and sonic searchers, all cultural inquisitors operating in one liminal space or another. In addition to the exhibition space there is an open-to-the-public reading library of artist’s books and zines and a radio frequency featuring experimental sound that you can pull up and listen to at 89.9.

The building has the hexagon-on-vacation glass façade and double bay garage of a mid-century gas station. It doesn’t mimic the extreme Utopian lines of Mars Gas that used to be on 4th Street just off University Ave., but I suspect that something Constructivist lurks within.

The building serves as the work space of COOPt founder J. Eric Simpson, Cody Arnal, and Aaron Hegert. COOPt member, curator, and writer Natalie Hegert has agreed to meet me this afternoon to see California artist Cara Ray Hoven’s Notes on Bells.

I’m here a week before the opening, which gives me the opportunity to experience the space as silence, stillness, potential. As it is, the clappers hang suspended above the inverted caps, metal half-spheres that balance precariously atop other metal objects such that contact with the clapper will veer from subtle ding to clanging topple, depending on the sensitivity of those moving about in the space. For me, alone, the multi-colored ropes anchored to the floor on one end and looped through the ceiling supports to dangle the clappers on the other, serve as a visual field that advises a dance with amused attentiveness.

A previous exhibition at COOPt was Sarah Aziz and Jack Craft: Tumbleweed Rodeo.

Sarah is a British Pakistani from Sowerby Bridge in the North of England, living in Lubbock. Craft came in for the project from Clarendon. Their project was a performative piece which invited a brand of fun-loving artist-driven chaos that cannot be contained within the confines of this acrobatic paragraph gleaned from the COOPt website:

“Drawing on their collective histories of parasitic engagement, domestication, and the retranslation of foreign phenomena, artists Sarah Aziz and Jack Craft will transport 800 cubic feet of tumbleweed from the Llano Estacado to CO-OPt Research + Projects and, with the aid of 6 Vornado fans, recreate a miniature tumbleweed tornado inside the gallery space. The space will only be occupiable by non-human forms of life, turning every strip-mall passerby into an ecological voyeur, gleaning insights into the rhythm between containment and shattering.”

As an avid tumbleweed collector, I can only shudder at the cavalier attitudes of these artists that shamelessly removed eight hundred cubic feet of them from the south plains.

I had wanted to meet up with Andrew Weathers and Gretchen Kosmo at their space in Littlefield on this trip, but they were also on the road. Collectively known as Wind Tide (also the name of their building), their Half Calendar, at COOPt last year, was a collection of large-scale collages, made outside in collaboration with the whims of weather, in the first half of 2022.

They are the core of Llano Estacado Monad Band, a loose collective of players and sound providers, using traditional instruments, farm implements, and anything else within reach to mine sonic territories random and directed.

Last stop of the day is Preston and Kelly Alison’s vineyard west of Lubbock. Our plan is to meet at sunset, but for that you need visibility, a rare commodity this evening. What we do have is an overcast sky and strong wind, which Preston casually circumvents in service to some fajitas he’s preparing on the grill.

The fire we are standing around is necessarily modest given the blustery weather, which is gearing up to last for the remainder of my time in the Panhandle. Each of us in turn adds a stick or two as we hand in the evening. At one point Kelly breaks into a full body demonstration on the movements of tumbleweeds. It’s true. They blow forward and they blow back.

Formerly Martin’s Vineyard, the place was dormant for five years. Now Boxing Rabbit, the Alison’s thirty acres features 22,000 vines near the middle of the 32,000 square miles of the Llano Estacado, the largest non-mountainous land formation in North America. They are two years into it and determined to reestablish it as a working vineyard. Their presence gives it a sweet outpost vibe, as if something akin to preservation is going on.

Kelly, in addition to her work in the vineyard and as artist, is the Founder and Director of the Contemporary Art Museum Plainview (CAMP), which since 2017 has offered an ambitious calendar of exhibitions, community programs, and artist residencies, which have included COOPt and most recently, Wind Tide.

Some of the work in Kelly’s studio is in preparation for a Jack Massing instigated group drawing show titled Texas Drawl, for which the invited artists collaborate via mail.

After touring the vineyard, we gather around the table for those fajitas. While Kelly puts together the tortillas and pico de gallo, I’m sitting in an exact copy of an Eames chair made by her dad, from a time when they lived on Buffalo Lake outside Lubbock. Kelly relates how her mom grew tired of the mid-century modern aesthetic, sending all the furniture to a watery museum at the bottom of the lake. Given drought and what we’ve been hearing about Lake Mead, I’m seeing an indoor oceanarium at The Bellagio in Las Vegas, filled with Rat Pack furniture akimbo in the sand at the bottom of the tank.

There is a kind of land-based art making going on out here that is somehow running in parallel with artists experimenting with sound works. Maybe it’s all this stretched wire that demarcates ownership, humming with a tone that can’t be possessed that creates a tension worth exploring. The exchange of influence and cooperation solidifies the area by geography rather than the demarcations of individual towns and cities. This sort of crossover seems especially vital out here where there is so much space. Collaboration provides connection in the absence of the kind of cultural compression that occurs in more urban scenes.

Sunday morning, I literally put on my cleanest dirty shirt and head north to Petro Truckstop on I-40 in Amarillo to see the chapel where Hayden’s father was a pastor some years ago. Spending about forty-five minutes there, I am convinced that anything resembling love and community at the chapel happened in times past. The sad fellow currently holding down the podium said he’s lucky if two people show up, and lamented that if no one does, he just talks to himself. Not surprising, given the shop-worn internet adumbrations he repeated during my visit.

The truck stop proper offers more hope in the form of LPs for sale: David Bowie’s One, The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, and Prince’s Purple Rain, among others. I head south to Canyon, imagining an eighteen-wheeler equipped with a turntable.

At Jon Revett’s place in Canyon, I’m greeted at the door by a congenial brown and white dog, Sheba, and Stinky, a blacker than black cat that moves around the house like a velvet shadow. It’s a comfy spot to hang and I’m lucky — Sheba and Stinky will sleep with me this night.

Revett teaches in the art department and is the Director of the gallery at West Texas A & M University in Canyon, where the current show is Kelly Alison’s Get Behind the Mule.

Her show is made up of paintings, mixed media works, and video. Her collage/painting hybrid pieces offer a view looking through a multi-layered field of dots, clouds, teardrops, time bombs, rain, sketchbook notes, swoops and ripples, roads to nowhere, tornadoes, thought bubbles, voodoo dolls, cracked earth, an automatic rifle — all these floating in an ambiguous field supporting whimsical images of sinking boats, dying sunflowers, and a couple of drowning man legs reminiscent of Philip Guston. Hands stand out in many of the works, most likely because Alison’s hard-working hands are quite full.

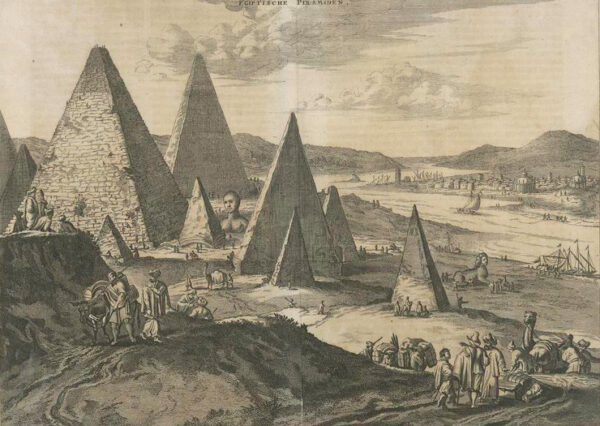

One of Revett’s works hangs in his office at school. Not the Pyramids offers an update to a story about Cadillac Ranch in which it was claimed that the angle at which the partially buried Caddies were set is based on the Pyramids of Giza. Whether conscious myth-making or a very persistently lingering Egyptomania, this rumor has persisted for decades, though obviously untrue. Sometimes it takes a very long time for yarns such as this to fade. It was believed until the Renaissance that the pyramids were the biblical granaries of Joseph, even though the historical timelines are centuries apart.

Revett’s 2018 looking north photo of one of the cars is abutted to Wyatt McSpadden’s looking south photo of the same car from 1974, when the installation was new. The opposing seventy-degree angles are a wordless, but not humorless, refutation of a perception or representation that has been continually repeated in news stories and on travel sites, though it seems worth noting that Charles “tail fins resplendent” Kuralt didn’t fall for it.

Olfert Dapper might possibly be responsible for planting the seed of misconstrued pyramid angles. His 1670 etching is fancifully convincing considering he never traveled to Egypt to see them.

Curator Alex Gregory is kind to meet us at the Amarillo Art Museum on a Sunday afternoon. The museum is currently hosting two shows, Achievement in Art, a collection of nineteenth and early twentieth century pastoral scenes and idylls and Gary Burnley’s Stranger (s) in The Village. The shows were brought together by Gregory to provide “some deeper contemplation” in their juxtaposition.

Daniel Ridgway Knight (American, 1839-1924), “Going to the Wash-House,” 1893, oil on canvas, 26 x 32 inches, Loan courtesy of The Smith Collection

Gary Burnley, “Kindred Spirits,” 2022, unique inkjet photo and mixed media, physical collage, 42 x 34 inches, Loan courtesy of the artist

Some other artists in the museum collection are Douglas Kent Hall, Dorothy Hood, Ken Little, Chuck Olson, and Theodore Waddell, who West Texas A&M and The Center for The Study of The American West are bringing for a lecture at the museum on April 20. Another event on the horizon at the museum is a show of Terry Allen works on loan from the Texas Tech Museum collection.

Douglas Kent Hall (American, 1938-2008), “Los Matachines—Amado,” 1982, gelatin silver on paper. Gifts of Cornelia Ritchie

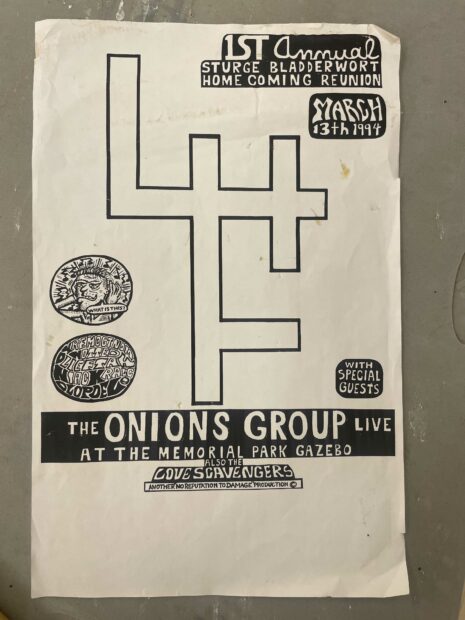

Meanwhile, we have arrived to meet artist Matthew Williams at Invisible Genie, his gallery where he has been featuring shows by under-represented artists since October 2020. The current exhibition is Lienad Kralc, otherwise known as Danny Clark, founder of seventies abstract sound outfit Onions, whose performances were sometimes shut down by police. In 2016, he jammed with a younger, noisier Hayden Pedigo at the first performance of Maggot Death, soon to become Plastic Mayan Staircase, an experimental project that acknowledged Onions as an important predecessor.

The afternoon is on the verge of a weather event, but before we head straight into it in order to explore Canyon, we’re going by Caliche, ironically named for a kind of growth-resistant soil common in the Panhandle. Appropriate because artists don’t need ideal conditions to operate. It houses a vintage shop, therapy center, Bitter Buffalo Records, and Lasso, a gallery where the current artist is Matthew Williams.

Lasso, born of necessity, was founded by Kegan Hollis in June 2021. An artist originally from Texico, New Mexico, who teaches alongside Revett in the West Texas A&M Art Department, Hollis is committed to the DIY scene in Amarillo, as is Williams at Invisible Genie. Hollis cites Louise Nevelson, Ant Farm, Georgia O’Keefe and Robert Smithson as Amarillo-related artists providing a foundation he wants to build on.

There is a history of artist-run-spaces in the Panhandle — Lubbock Lights, founded and operated by Deborah Milosevich and Lora Hunt in the seventies and early eighties and the Wheeler Brothers Studio in Lubbock in the two-thousands, are some notable examples. Lasso and Invisible Genie in Amarillo, COOPt in Lubbock, and CAMP in Plainview are part of the current community in which cooperation obscures any one set of city limits.

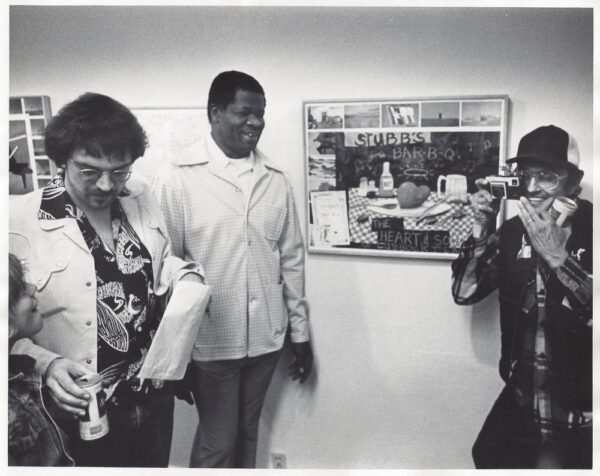

Terry Allen, Stubb, Paul Milosevich at Lubbock Lights, 1978. Photo by Jim Eppler, Courtesy of Paul Milosevich

Williams’ exhibition at Lasso is a multimedia affair including documentation of staged and live performances since he returned to live in Amarillo in 2008, following a period when he lived in London. He also lived for a while in New York, where he was repeatedly mistaken for Arrested Development actor David Cross.

Riffing on the notion of fluid identity, Williams took the mitigation a step further by miming the moment when his doppelganger’s character, Tobias Fünke, attends a performance of the Blue Man Group under the impression that he is going to be attending a support group for depressed men. He comes home from the encounter signed on as an understudy and paints himself blue in prep for an audition.

Titling his piece after the episode, “I Blue Myself,” Williams staged a recreation of the moment in the show when Fünke, standing in his kitchen, muses on the mysteries of the universe, saying to another character, “You never know where help is going to come from.”

This phrase echoes pretty precisely just the sort of phrase that would have been at home in another project Williams was part of, the Dynamite Museum, a Stanley Marsh-funded project, in which a series of three thousand signs were set up all over Amarillo.

A sampling of phrases on the signs: accidents happen even in the best run universe / I slew a worm / lone wolves are seldom seen in threes / we know so little about the causes we actually serve / no job no food no rent / it crept into my hand honest / the fog comes on little cat feet.

A replica of such a sign within the Cadillac Ranch diorama at Hayden and L’Hanna’s house advises, “Don’t end up with more dollars than sense.”

The signs, many of which may still be seen around town, were erected by a loose collective of artists and friends that included, in addition to Williams, Jon Revett, Drew Mason, Larry Bob Philips, Danny Clark, and Brad Holland.

Williams’ I Blue Myself was created during a ten-year project titled The Color Path, in which the artist wore red, yellow, blue, black and white (or a combination thereof) and made art correspondent for two years per color. Marshmallow Monk was a character dressed in white robes and performed by Williams during Lubbock’s most recent S#%& Show in response to the prompt, “The year 2050,” in which the monk is part of an apocalyptic scene where religious zealots swap vaccines and roast marshmallows.

Amp Recording is just down the street from Caliche. Yet another locus of Panhandle experimental music for a time in the nineties and mid two thousand teens, it is operated by Drew Holder, whose current project is Lava Tone. A story goes that Randy California’s soundboard has gone to good use at Amp since it wound up there by happenstance some years ago.

The NAT, a fixture in the same 6th Avenue neighborhood as Caliche and Amp Recording, was a natatorium built in the twenties that only lasted as a public pool for a few years before becoming a dancehall. In 1956, Little Richard was famously arrested by a naïve District Attorney who was in the right place with the wrong mind and couldn’t handle it. Nowadays, The NAT, like Whitewood Lanes in Lubbock, has been supplanted by an antiques emporium.

Jon and Matt are a good pair to scan the art under belly of Amarillo with. In addition to their knowledge, they have the conversational patter of friends that gives a good vibe to the ride.

Hereford, I will mention right here, has some colossal grain elevators. Among the first great unions of Modernism and concrete, these magnificent structures were hailed by Walter Gropius as comparable to the work of the ancient Egyptians.

Could it be that the story about buried Cadillacs and Giza is suffering under the burden of monument-envy?

I’m looking forward to admiring these concrete marvels again, as they are on the road I will take tomorrow, under clear skies, returning to New Mexico, but for now we are venturing that direction toward Umbarger to see a church, a dam, and a dairy (but no shaggy dog).

Just before heading that way, we cruise “the cowboy,” a splendid example of mid-century monumental kitsch, built in 1959 of concrete and steel by high school shop teacher William Wheeler. It has withstood more resistance than is fair for a 47-foot cowboy, now restored and seeing better days than those during which he was wind whipped and truck dented, with his damaged boots full of stray cats. Now he serves as the perch for dozens of pigeons while gazing down at vehicles entering Canyon on 60 East from Hereford.

You want to know what happened to the cats.

That was my question too.

It is one of those days so tormented by wind that we have to use our feet to get the truck doors open. Got out, let the doors slam, and we slipped into a side door of the church, gaining respite from the gale.

The interior features art by Italian prisoners of war who bore their loyalty to Mussolini in the way they slipped swastikas into the negative spaces between crosses on the reredos that flank the pulpit. A large animated letter M dances opposite, high above.

The red brick dairy rises up out of the flat plain with trees growing out of it and a severely damaged roof supporting twin, nicely aged barn cupolas that rival the height of two adjacent silos. The telephone wire, normally drooping several feet, is blowing at a severe angle and whispers that a Larry Bob Phillips painting is rumored to remain within the building, tucked up somewhere under the rafters.

The weather drama only increased after we left the dairy to not see the dam, which was completely obliterated by the dirt blizzard we were driving through. Apparently, this dam is something to see as a monument to bad judgment, made as it was out of the wrong kind of concrete—not the grain elevator kind, not the 47-foot cowboy kind, but the kind that doesn’t hold water. The kind that won’t work for a dam.

Just after leaving the dam, we encounter a wall of self-determined tumbleweeds blocking our flow.

Next morning, our coffee is witnessed by a Jim Harter print that hangs in Jon’s kitchen. Blue mountains, yellow stag, purple sky, diamond octagon. It looks at you as much as you look at it.

Sheba and Stinky give me goodbye rubs, touches, and lean-ins, before I hit the road with a plan to just swing through Palo Duro Canyon to say hello to a favorite Cow Cabin, before heading east toward New Mexico.

I’m going by way of Hereford into Tucumcari, before hitting NM 104 into Las Vegas, eventually to meet Paul Milosevich at his Santa Fe studio. Somewhere between Canyon and Hereford I came upon a situation in which two windmills were so close together that they created a singularity, a rare event in which infinity comes suddenly to bear in otherwise ordinary circumstances.

A singularity caused by proximal windmills. Another one is forming in the deep background by two adjacent identical buildings.

Later on, somewhere on 104, a perfect triangulation arises between a tall antenna, the wide horizon, and the road stretching past it. For a series of miles, these three basic units of reality are all there is. I’m just lucky to be here to witness it.

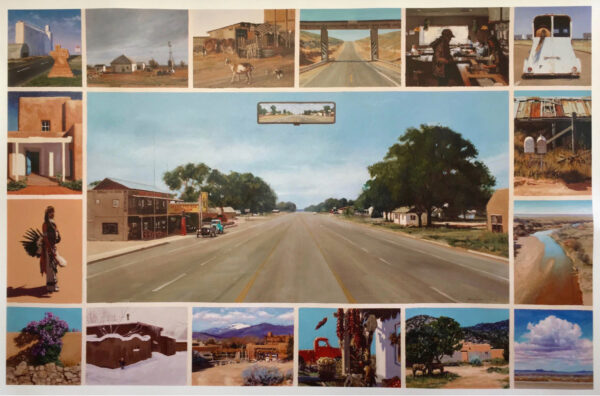

As I drive, I’m thinking about a certain Milosevich painting, From Lubbock to Santa Fe, which features a view through the windshield of a car as it is driven into Ft. Sumner, New Mexico. A rear-view mirror hangs like a promise in the sky above the road.

Images from Clovis Road out of Lubbock toward Santa Fe are aligned around the edges of the painting as postcard views of specific places, such as a Pecos River bank, a Ft. Sumner railroad bridge, and an image in the upper left corner in which, for compositional balance, a Dairy Queen that was on the north side of the road is inserted on the south side of the road, opposite a grain elevator on the north side. The actual site is near the state line at Farwell, TX.

Paul Milosevich, “From Lubbock to Santa Fe,” 1993, oil on canvas, 48” x 72” inches. Karin & Shelby Miller (Denver) collection.

Milosevich’s affection for Terry Allen is obvious in the stories he likes to tell, such as his account about the opening for the exhibition that Lubbock to Santa Fe was first shown in, Before There Were Borders / Beyond Imaginary Lines, at Gallery at The Rep, Santa Fe, curated by Kelly Cozart in 1993. To Milosevich’s lingering amusement, Allen took mock umbrage with the relocated Dairy Queen, adamantly suggesting that moving one is outside the bounds of what artistic license may allow.

Once again, I’m sensing a singularity, which may have occurred in that split second when the DQ could still be seen slowly disappearing on the northside, as it was being transferred via paint to the south.

The light that reflected on my face when I stood before one of the most pristine of the Hereford grain elevators is now illuminating our conversation and Milosevich immediately snaps to My Egypt, a painting by American cubist/precisionist Charles Demuth.

Like a window in the temple of modernism, as seen through Duchamp’s Large Glass, with shards courtesy of T.S. Eliot, My Egypt was the first piece made in the architectural series that Demuth began in failing health near the end of his life. In the painting, a grain elevator fills the canvas, obliterating any view of the horizon or the future. Demuth’s Egypt is grain elevator as tomb.

Charles Demuth, “My Egypt,” 1927, oil, fabricated chalk, and graphite pencil on composition board, 36 x 30 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney © artist’s estate

Milosevich has a kind of sly dog humor that feels like he’s had it from an early age. Amusement is in his eyes when he showed me a hefty coffee table book that he had just received commemorating one hundred years of Texas Tech. The book contains a nice spread about him and mentions that he was a bit of a misfit at Tech, clearly tickling his sense of irony.

I don’t have to check the contents to know that Mike Leach is not included.

Milosevich was a realist-painter-peg not really fitting into an abstraction-hole at Tech, given that many of the faculty were more firmly fixed in the flow of late twentieth century field painting and conceptual art. He cites portrait painters Raymon Froman and Wayne Thiebaud as influences and is currently intrigued by Russian painter Nicholai Fechin, who came to Taos in the Twenties and whose house is now the location of the Taos Art Museum.

Nevertheless, it was Milosevich’s prowess as a portrait painter that allowed him to leave his tenured position at Tech. Tom T. Hall, Waylon Jennings, and Joe Ely are among many musicians whose likeness Milosevich has nailed. It was Hall and Crickets drummer and Buddy Holly collaborator Jerry Allison who encouraged him in different ways to step outside the confines of academia and go for it.

Today, Paul is working on a couple of portrait commissions and pulls out a painting he wants to finish. The subject is the ’56 Pontiac that was “J.I.’s and Buddy Holly’s double date car.” Shenanigans are cited and Milosevich allows that when Allison moved to Nashville in the seventies, he gave him the car. In a move that reminds me of William T. Wiley’s Slant Step, an artwork that cannot be said to belong to just one artist, Milosevich later passed the car on to writer Michael Ventura.

In the painting-in-progress, the tell-tale shape of Fisher’s Peak, outside Trinidad, Colorado, where Milosevich was born and raised, is in the distance behind the car.

Outro

They met in the parking lot of the Velvet Taco at 9 PM. He appeared in a Nudie suit the color of dry Llano-Estacado cedar. You could call it green, but it was more like a natural iridescence between dust and rust.

She was wearing an Orange Julius employee top that she’d bought on impulse at a second-hand shop in Muleshoe and some sleek Creamsicle slacks.

They both had good shoes.

Their plan was to photograph every grain elevator on Clovis Road in moonlight and they wanted to look good doing it.

Song lyrics from “The Tender Trap” by Sammy Kahn and Jimmy Van Heusen / “Heaven” by David Byrne and Jerry Harrison.

3 comments

So good, thanks for the ride.

Barbara, I enjoy the rides your writing takes me on too!

You took me to a world that might have been but a dream, had you not memorialized it as real. THANK YOU!!!