In an unassuming hallway gallery at the Museum of Texas Tech University, abstract works from the permanent collection are currently on view. That is to say, they’re up and out of the vast storage in the museum’s basement, and put together here with the loose rubric that the works contain primarily geometric compositions.

Plane and Solid: Geometry in Art consists of mostly shape and colorfield-based flat artworks with impressive range, considering the restrained number of works in the show — there are fewer than 20 pieces on display. There are demonstrative pieces of the type, like an Ellsworth Kelly and Max Bill, but my favorites on view are the ones that barely slip into the party with the other formalist studies.

Jeffrey Dell, Mint Condition, 2013. Screen print (19x 13 1/2 inches) Museum of Texas Tech University, gift of the artist.

TSU professor Jeffrey Dell’s silkscreen Mint Condition is what appears to be a bent, fluorescent piece of striped gum or taffy, with an acrid red-orange stripe flanked by pastel peach and a tinge of minty green dissolving one tip. It’s really technically impressive work, with a finish fetish that’s hard to come by through this particular medium.

Mamigon, an embossed screenprint by Garo Antreasian (active in Albuquerque and the father of the Tamarind Institute of Lithography) is nearly impossible to photograph with its matte black surface behind framed glass. Compared to other works in the show, it functions differently: The physical texture of the print and the flat void it insinuates make Mamigon an object or a barrier to space, as opposed to the optical illusion and equally confusing planar space in Josef Alber’s I-S VVI.

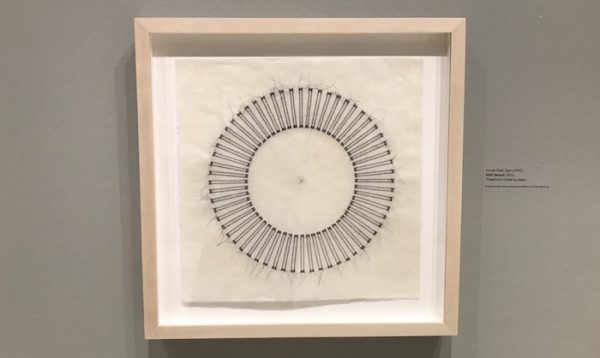

Linnea Glatt, Split Second, 2006. Thread and mulberry paper (18×14 inches). Museum of Texas Tech University, purchased with funds provided by the Helen Jones Foundation, Inc.

Dallas artist Linnea Glatt’s bitingly literal Split Second, made of thread, looks like a clock or “activity indicator” (the spinning animation you see while something uploads or buffers on a screen); it’s another pleasant surprise here. I guess I wasn’t expecting the objecthood of the artworks to play such a central role in a show with this title and bent. You certainly wouldn’t guess it from the exhibition’s PR, but I think this is a good thing.

The accessible artworks in stored collections are one of MoTTU’s greatest assets. It’s fairly simple to email and set up an appointment with museum curator Peter Briggs to see the extensive collection of works on paper, and more, above and below the main floor of the museum. The AP/RC (Artist Printmaker/Photographer Research Collection) upstairs houses collections of prints, sketches, proofs, and entire bodies of work from individual southwestern printmakers. There are a lot of them. Briggs defines “southwestern” as someone who has been in the area forever, or even just long enough to “sneeze in the region.” To be able to research an artist, genre, and/or process in depth, without having to deal with a lot of administrative red tape, is pretty special.

As a Lubbock resident, I’m grateful Briggs puts on these smaller, quieter, exploratory shows. Special exhibitions like Plane and Solid are vastly more interesting to me than what is always on the museum’s permanent display: the expected cowboy paintings; a room of N.C. Wyeth illustrative paintings (actually, those are great); and a sculpture collection. The contemporary southwest collection rotates every so often, so go see that, too.

‘Plane and Solid: Geometry in Art’ is on view through Sept. 9 at the Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock