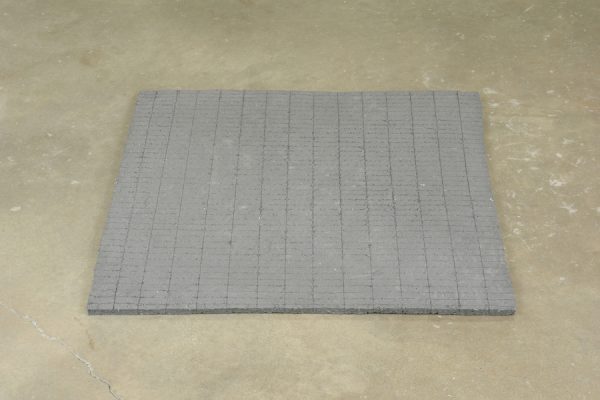

Tino Ward, Untitled (after Donald Judd), 2020. Linen and cotton rag paper, latex enamel, wood. 6 units: 20 x 20 x 20 inches. 12 feet 8 inches installed

Not Macho.

“The materials do what they do and don’t refer to anything else.” This terse phrase sums up the artistic ambitions of quite a few artists of the 1960s. In particular, the artists who came together in 1966 for the historic exhibition 10 at Virginia Dwan Gallery, New York.

10 was conceived by Dwan and Robert Smithson. Ad Reinhardt, who had mounted an exhibition of near-black paintings in 1963 at Dwan’s Los Angeles gallery, suggested the inclusion of Agnes Martin and Robert Morris. The final roster also included Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, and Michael Steiner. The title of the exhibition simply refers to the number of artists participating in the exhibition. Nothing in that nondescript title hints at the underlying aesthetic tensions that permeated the group. The works displayed in 10 figure in our imagination as markers of the soul of an artistic movement that would become known as Minimalism. Yet such an unproblematic lumping together of disparate artists is now viewed as a rather unfortunate, if convenient, fiction. Even at the dawn of so-called Minimal Art, the artists of 10 would not go quietly into that good night of art critical mummification; in fact, they never thought of themselves as constituting a group. While Smithson penned what he had hoped would be a joint statement for the exhibition, there was no consensus to support it. At the opening of 10 some of the artists wore a button that read, “Smithson is Not My Spokesman” [sic].

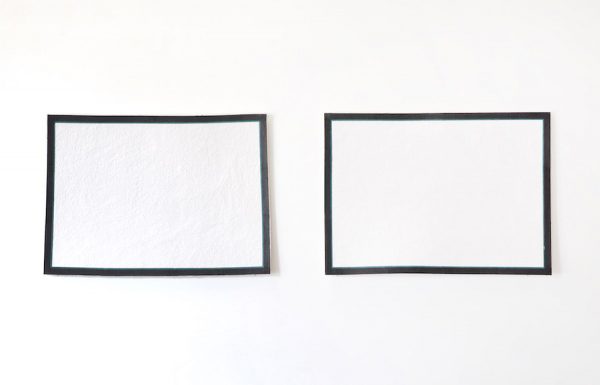

Tino Ward, Horizonal Flanking: small scale (after Jo Baer), 2020. Recycled Paper, latex enamel. 30 x 42 inches each.

More than one-half century later, 10 and what followed in its wake still manages to exercise the imagination of makers and interpreters of art. Enter Tino Ward, whose interest in 10 stems from a broader interest in Minimalism as well as its elusive existence provided by the evidence of a couple of installation photographs. In Texas, the search for representative works by each artist in 10, save Michael Steiner, will be rewarded. Travel to Marfa to see more works by Donald Judd and Dan Flavin than are held by some of the most well-known museums in the world. Venture farther out to Taos, NM and a suite of works by Agnes Martin awaits you. If you really put some effort into it, you will discover works by Robert Smithson, Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Sol LeWitt, and Ad Reinhardt in Texas — though not necessarily of the same period as 10 and not necessarily currently on view in the collection or museum where they are held.

I don’t know if Ward went to the trouble of launching into an aesthetic pilgrimage in order to stand face to face with the works of the artists of 10, but he does profess a keen interest in Minimalism and did research the original exhibition. While the reconstruction of an historical exhibition is itself a daunting project, Ward has added a layer of complexity by choosing to exercise his expertise as a papermaker and fabricate copies of the original works using paper pulp, cotton pulp, and wood. The result is After 10, a stunningly beautiful one-quarter scale reconstruction of all the works in the 1966 exhibition. It is a moving reconstruction of the past, represented in hand-made paper and appearing as if an apparition or the hazy image of some half-remembered experience.

What intrigues me about Ward’s installation is not necessarily its reduced scale. The model of Donald Judd’s Untitled is sufficiently looming despite its being somewhat reduced. Because of the vagaries of its fabrication using handmade paper it is deliriously multi-toned, unlike the strict monochromatic surface of the original. Even in reduced scale, Jo Baer’s diptych, Horizontal Flanking, is impactful but with an ethereal quality due to the warping of the material. These features of Ward’s replicas are notable, but I would caution the viewer not to assume that such departures from the material specifications of the originals signifies their diminishment or necessarily represents a harsh criticism of the entire enterprise of Minimal Art. If that were Ward’s intent, why go to all the trouble of remaking the originals using handmade paper?

It’s important to mention the widespread artistic strategy known as “domesticated Minimalism”. That unfortunate journalistic cliché was coined during the 1980s by Roberta Smith, the lead art critic of The New York Times. Its purpose was to disparage the reworking of Minimal Art by younger, mainly non-male, and frequently non-white, artists who configured into geometric forms suggestive, unconventional materials like chocolate or grease. These artists were keen to demonstrate their disapproval of what they took to be Minimal Art’s exaggerated stress on formalism and its cultural role as a badge of white patriarchy.

The art historian Anna Chave endeavored to put an end to this narrow-minded fantasy of power and glory with her article, “Minimalism and Biography” (2000), a scathing rebuke to the “official,” exclusionary history of Minimal Art. Subsequent art historical accounts — for example, James Meyer’s Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (2001) — have enlarged upon Chave’s judgement and reconstituted Minimalism as an artistic tendency that, in the words of Sol LeWitt, has no limits. Regardless, artists identifying as women and artists of color have all reinforced with great advantage the connection between Minimalism, flawlessly fabricated geometric structure, and naked white male power.

For so many young artists of the 1980s and after, the cultural capital of Minimalism was based almost entirely on the fact that its most enthusiastic collectors numbered among the most powerful enterprises of capitalism, for whom such work’s impeccable industrial finish, gigantism, and obdurateness complemented the glossy efficiency of their corporate ethos. It is important to note that this is not Minimal Art’s appeal for Ward. Why is Ward fascinated by Minimal Art, at the precise moment when such a seemingly bloodless conception of art is woefully out of step with the practice of virtually every young artist one can name? Why promote an art that treats the materiality of the object with little or no concern for its cultural significance?

Tino Ward, Daylight and Cool Light (after Dan Flavin), 2020. Handmade paper, wood, fluorescent, latex enamel. 24 x 4 x 4 inches.

There are other perspectives on Minimal Art to consider, especially the points of view voiced by some of the artists themselves, who chafed at being labelled minimalists by the critics. Because Minimal Art is in actuality heterogeneous and not exempt from alternative interpretations, we glimpse the irony of Ward’s treatment of it. While the dominant art of our time is steeped in cultural and political issues such as identity and their transparent communication, we can argue that Ward’s reconstruction of 10 manages to allow concerns with embodied perception — the relationship between the physical body, sensation, and thought — to shine through. Needless to say, such concerns parallel our current obsessions with experience and total environment immersion through art. One might object to this conclusion by pointing out how Ward’s choice of scale compromises any sense of embodied experience and makes a travesty of Minimal Art. Such a rejoinder strikes me as an unwarranted concession to the very historical stereotype that is being challenged here. Given Ward’s astute historical perspective plus the inspired choice of paper as the material of fabrication, my belief is that his interest in the past is warranted.

Tino Ward, Algodon (after Robert Smithson), 2020. Cotton, ink. 7 units: square surface dimensions 1 1⁄2 inches; 1 3⁄4 inches; 2 inches; 2 1⁄4 inches; 2 1⁄2 inches; 2 3⁄4 inches; 3 inches.

Each of the copies in Ward’s garden of delights is anything but “minimal,” uninflected, or unsuggestive. The surface texture, color, and form of Ward’s works invites inspection and demands a particular attentiveness from the viewer. (This is not to say that an uninflected surface is less compelling, but merely to reinforce a historical view of the matter. An uninflected surface accompanied by large scale or the encompassing of one’s field of vision is the hallmark of many works of Minimal Art that are equally deserving of our attention.) To be clear, Ward’s project is distinguished from previous critical revisions of Minimal Art by the sense in which his antithetical treatment of surface and scale refuses the path of parody or transforming the object into a performative prop. Ward’s work is quarter scale yet replete with incident, a tangle of suggestive, beckoning nooks and crannies begging to be touched, explored, and puzzled over. Bear in mind that the negation of surface incident found throughout all the works in 10 — the sleek, industrial finishes, the painted surfaces revealing no brushstrokes, the unmodulated monochrome hues — is the one formal quality they share; the singular judgement upon which their identity as artists depended, the distinction marking them off their objects from those of their older colleagues, the Abstract Expressionists.

Tino Ward, Ultimate Painting #39 (after Ad Reinhardt), 2020. Recycled paper mounted on wood.

30 x 30 inches.

Having never viewed 1966’s 10, my memory of the exhibition is indirect. But I am sufficiently familiar with similar works by all the participating artists to be nonplussed by the scale of Ward’s works. I constantly had to resist judging Ward’s achievement by that criteria. Some of his reconstructions — particularly the attempt to reconstruct a near-black painting by Reinhardt — suffer by being too close a copy of the arguably inaccurate photographic — or media — image of the work. Reinhardt’s late dark paintings are notoriously difficult to reproduce photographically and are frequently referred to as “black” when in fact they are not. But this chromatic ambiguity is a crucial perceptual aspect to the painting that Reinhardt worked assiduously to maintain. So, stare as you might, for as long as you might — the chromatic perceptual effects of an actual late dark painting by Reinhardt will never materialize. Fortunately, this is the only instance in my experience where Ward’s project wobbles.

So, what is Ward’s point? Our encounter with each of the works foregrounds sharply the experience denied us where were we to have no knowledge of the originals save that provided by documentary photographic evidence. Cast adrift, our encounter with Ward’s works constitutes a powerful critique of representation. We may know of these works, but do not really know them if we are unable to be in their presence and to experience what it is that they can do to us. What is more, Ward’s project suggests that even if we were to encounter a group of such works, at full scale, how certain could we be that we would be able to appreciate the special qualities of each without bending to an a priori conception of Minimal Art? This is not to say that we can approach this art, or any art, with an innocent eye; rather, that this art in particular has been reified to such an extent that to be able to recover something of its initial logic or impact is almost beyond reach. A similar fate has befallen Conceptual Art, which now exists as the cultural commonplace, whereby every artist with an “idea” is considered a child of conceptualism. In this exhibition, Ward provides us with a number of gifts; we are instructed about the mendacity and poverty of the image as a bearer of meaning, and also thrust headlong into a debate with the crude, overzealous critical judgments of the past. In Ward’s show, we learn that the challenge of actually looking and attending to art is more difficult than coining a phrase or being led by a buzz word.

Ward has looked intently — deeply — into the realm of what Donald Judd called “specific objects.” Above all, Tino’s process of fabrication has enabled him to translate the works of the exhibition 10 into objects that are multivocal. The practical issues encountered in the remaking of any one of the works of 10 in paper were formidable, but it was only through this tortuous process of reconstruction using the most inopportune materials that Ward was eventually able to glimpse beyond the popular, received idea of Minimalism. To reiterate, there is no intention to simulate the experience or appearance of 10; what you see is a sample that doesn’t exemplify the model.

Tino Ward, Untitled (after Robert Morris), 2020. Linen and cotton rag paper, latex enamel on wood. 4 x 4 x 2 feet.

Ward’s translation of 10 lends something to the form of the original works that they never had and, in fact, worked hard to avoid: a whiff of the pictorial. It is absolutely the case that the original works of 10 resisted the use of materials in such a manner as to “speak” the language of expression. In reply, Ward insists that the works must be seen as if they are fluent in today’s symbolic, cultural use of materials — specifically, their handmade fabrication from recycled cotton and paper.

A final word: a catalogue accompanies this exhibition and in keeping with the spirit of the work, it follows the format of the original but does not resemble it. In Ward’s publication, the Risograph process used to print the installation view and individual images of the works imparts a grainy appearance to the reproductions. Consequently, the catalogue is in sympathy with the exhibition.

Extended through July 18 (by appointment) at ex ovo, Dallas.

Michael Corris is an artist and writer on art.