The group show INTERWOVEN, on view at MASS Gallery in Austin, feels like a response to our ethereal modern existence. It’s based on the physical, tactile use of fabrics, and while this is, admittedly, a lens hampered by contemporary references and technology, that sense (or loss of sense) seems to be the very one the show addresses.

INTERWOVEN showcases the work of three Texas-based artists and three from elsewhere in the US: Suzanne Wyss (Austin), Haleh Pedram (Richmond, VA), Orly Cogan (Hudson Valley, NY), Amada Miller (San Antonio), Melissa Cody (Flagstaff, AZ), and Fort Lonesome (Austin, TX). Though vastly different in their textures and compositions, all the works in the show address physicality in one way or another — not just in their material choice, but in subject as well: a meteor, a landscape, hunger, the sexual body, the body politic, and the very space the viewer’s body occupies. There’s often pleasure in being reminded of one’s physical existence by art, and each work does that on its own terms.

MASS Gallery’s new space is intimate compared to its last one (this is not a bad thing), and when you first enter the gallery, it’s hard not to gravitate to the work of Haleh Pedram. Her larger-than-life bag of potato chips slouches against a wall, and nearby a retro golden sunburst bench full of foam promises a comfortable sit. It’s aesthetically pleasing, but more gratifying is the opportunity to touch something in a show composed of objects that entice one to touch.

Not long ago it seemed like I couldn’t go to a thrift store without finding vintage sewing patterns for giant hotdogs and Oreo cookies, all (if realized) big enough to lounge on in bell-bottom pants. Pedram’s potato chip bag brings those patterns to mind. But what’s compelling about the work is Pedram’s use of waste material from her upholstery business — trash, essentially — to recreate valuable (and seductive) objects that still evoke trash.

Overlooking Pedram’s bench and potato chip bag is an embroidered work by Orly Cogan, Alice in Blunderland. Here she has dickheads (by that I mean people with penises for heads) and characters riding cock (I mean straddling a phallus as one might ride a horse) — while farting. At the center of the work a nude, heavy lidded woman blows a cloud of smoke. It’s off-putting and yet also likeable, in a way that conjures vacuousness; the piece blends its depravity and innocence to surprising effect. Cogan creates a visual narrative about pleasure, abandonment of social norms, and perhaps just regular old blunders through life.

Works from Amada Miller’s Framing an Observable Universe series occupy one corner of the gallery. Images obtained from NASA show cross-sections of meteors printed on silk chiffon, and the effect reads like glass. In this instance, the material serves to convey an experience or idea, as the fabric holds the light in such a way that the colors are both muted and vibrant. There’s something mystical in this work, in that it feels like the mystery we attribute to outer space, or perhaps the wonder that space inspires.

In another nod to space and the planetary: Fort Lonesome’s tapestry-like In a Summoning They Come depicts a scene that’s indeed lonesome; this desert bonfire seems like it could be on any planet, the way nature sometimes feels alien. The work requires you to get close to appreciate the detail of the dense chain stitch, and yet once you’ve pulled away, you take in the fuller landscape, with its own topography and natural formations.

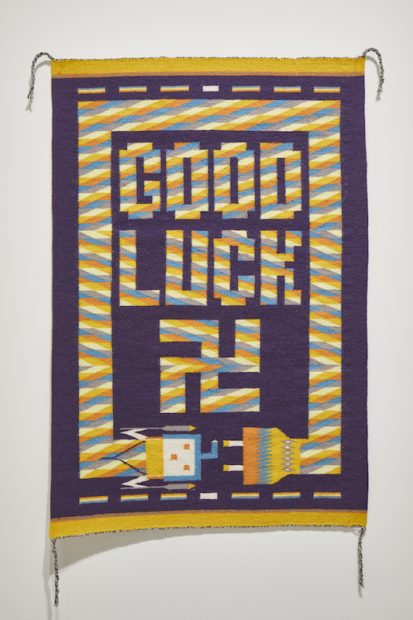

The last work along this end of the gallery is a woven piece of traditional-turned-non-traditional content. Good Luck by Melissa Cody places the text “GOOD LUCK” over a (traditionally reversed) swastika. In the present political climate, this veers into weird territory. Or is it simply that my contemporary upbringing makes it impossible for me to see the symbolism without bias? The swastika — a symbol the western world has come to associate with Nazi Germany and all its attendant horrors — was of course used prior to that for thousands of years by native tribes (and throughout Asia) as a symbol of luck and well-being. Perhaps my own tunnel vision is a problem, or perhaps this is Cody’s reclamation of something historically sacred, or perhaps the message is simply earnest and optimistic. In the context of my bewilderment, it is the last possibility that feels the most subversive and radical.

The final work in the show, a large installation to the far left of the front door, is a surprise — not only for its extreme material departure from the rest of the work in the space, but because its imposing presence makes it hard to believe that it doesn’t make itself known sooner. Suzanne Wyss’ Oil & Honey is macabre and quite gorgeous. Made of black and feathery used bicycle tubes and VHS tape, the piece hangs from the ceiling with authority. Because of the consistent use of these smoky and breezy black materials, each view from a new angle feels like the revelation of a secret. Some nooks feel like spines, while others read like the tines of a flower petal. This piece is a sort of adventure, and yet another reminder of the curious construction of our physical lives.

On view at MASS Gallery, Austin, through March 2, 2019