Putting the raw power of guitar-driven music into a picture is difficult, but Carlos Hernandez pulls it off in his current show Hard Luck Honky Tonk at Flatbed in Austin. Combining a selection of concert posters he’s designed for acts like Los Lobos and the Black Keys alongside his larger monoprint pieces, the show marks a new and fertile direction for Hernandez.

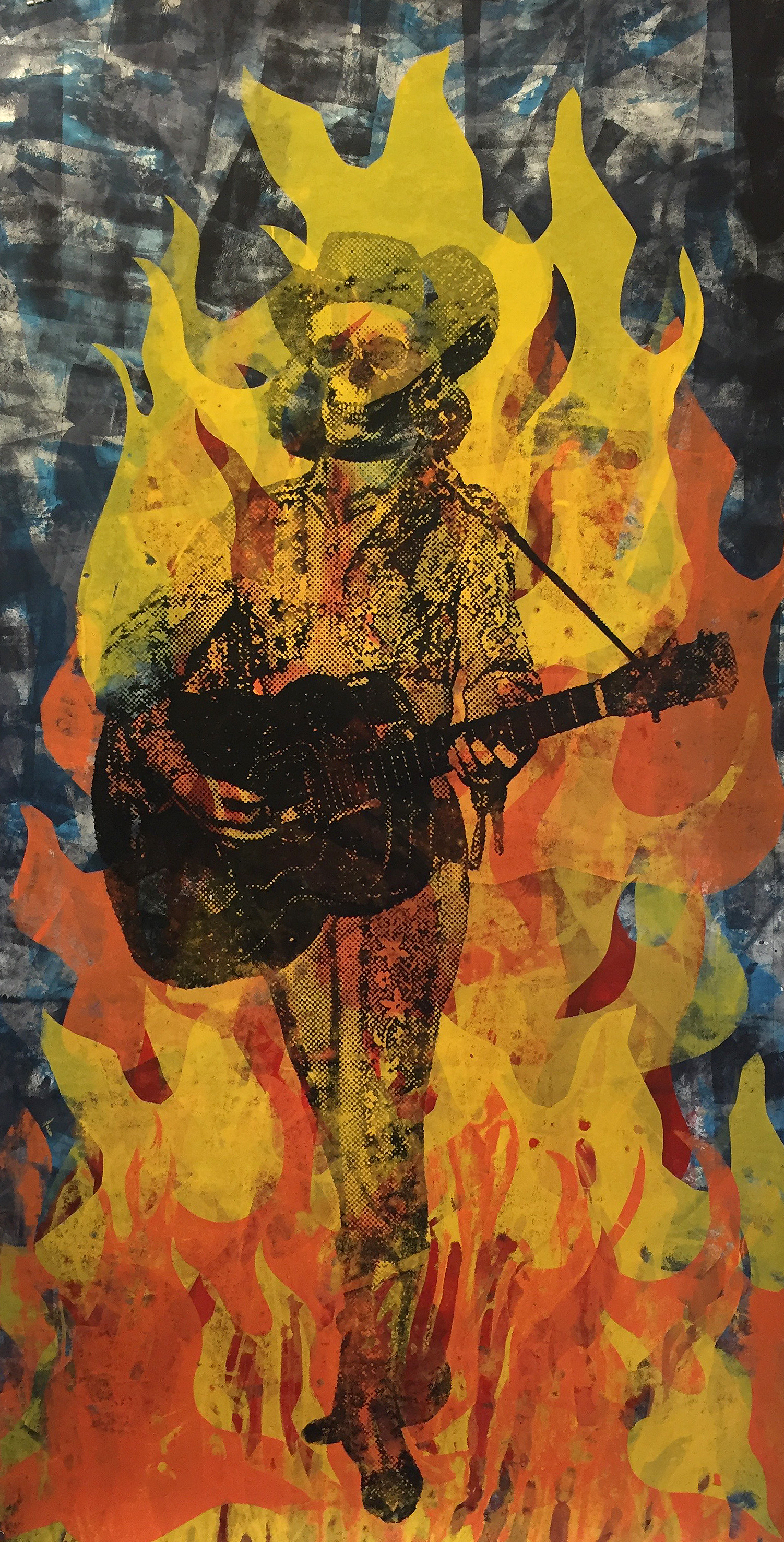

Beyond being a co-founder of Burning Bones Press in Houston, Carlos Hernandez is a well-known designer and screen printer. He was featured in 2011 and 2012 Communication Arts Illustration magazine for his topography designs; he’s been involved in promoting bands through his designs for seven-plus years, and has, in the tradition of concert posters, developed an ultra-expressive style that maximizes color and spastic lettering while embodying the explosive energy of the musicians he’s representing. Distinct to the concert posters in his Flatbed show is his use of folk imagery. Roughly drawn skulls, armadillos, and chupacabras appear over backgrounds of crude, roaring flames. His letters bend around each other, and their fonts switch from block lettering to cursive and back again. These images hum with visual feedback.

Opposite these works in the show are a group of small prints. Here’s where we begin to see Hernandez shifting his focus from the rougher edges of rock and roll to a new aesthetic, one laced with cowboy humor: Pistol Packin Mama features a dated ad sheet (for an array of adult industry products) overlaid with a 1960s pin-up cowgirl with her guns drawn. She crouches in a ring of fire like many of Hernandez’s figures in his concert posters, but she nods to the larger monoprints that make up the majority of this exhibition. With their use of recycled imagery and nostalgia, these smaller compositions set the stage for his most recent pieces, which are more fully realized and politicized artworks.

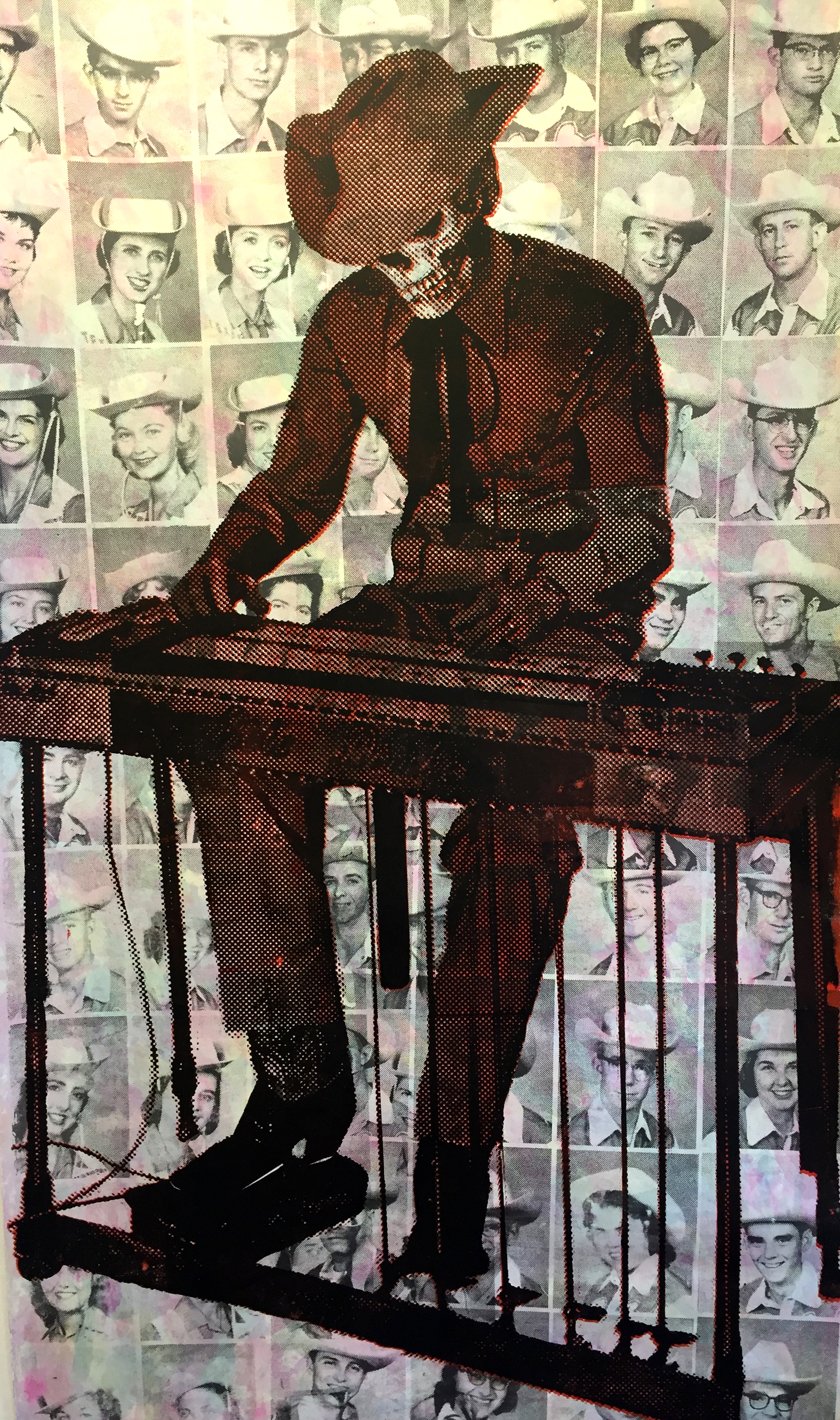

Significantly larger than the other posters, works such as Old Country and Public Figure No. 1 blend iconic imagery from the classic country era of the 1950s and ‘60s with a post-industrial sense of gritty mass production, commercialism, and surprising cross-cultural referencing. Here, our steel guitar player is a member of a Dia de los Muertos Calavera skeleton band playing against the faded, gridded backdrop of yearbook-like portraits of young cowboys and cowgirls. In another, a traditional cowgirl is surrounded by a dense abundance of color and flowers, and wears the black-star eye makeup we’d expect to see on members of ‘70s-era KISS or in even more recent tattoo imagery. And in another, a wall of headshots titled Whiskey Soaked Years gives us a long view of the grand narrative of a music scene. So many faces of musicians, who at one time or another were iconic to the regulars at regional honky-tonks, are now lost beneath the mass production of an increasingly impersonal music industry. If you look closely, you see that some of these faces have even been vandalized with those cartoon lips and eyes.

The one piece that for me summarizes this new body of work is South By South Mess. We know the commercialization of SxSW is complete, and Hernandez nods to that here. Replacing our cowboy’s horse is a Vespa scooter with the state of Texas silhouetted on its leg-shield. The cowboy roars through, leaving a trail of fire as he revs that little 8.7 horsepower motor to the max. The hipster rides again.

These images are caricatures of an industry. These Hernandez cowboys call back to a specific moment in American history; they symbolize the post-World War II era that witnessed the first color television sets and the fear of Communism. But in our current hard-luck honky-tonk of culture static, they also reveal how this mythic past era is so completely controlled and reshaped by endless new trends and idealizations. Hernandez hasn’t shied away from this. He knows icons fade, are recycled, and take on new meanings all the time, for better and for worse.

Through April 30 at Flatbed Press, Austin