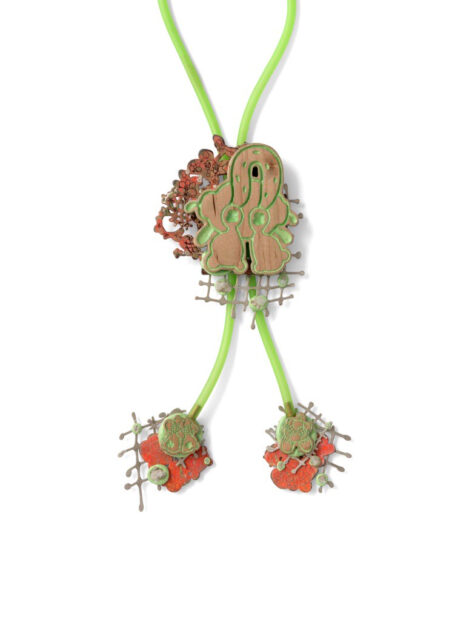

Left to right: Brian Fleetwood, “Pvkpvke” 2023. Jonah Hill, “Paa’qwa Prayers,” 2023. Ana M. Lopez, “Pneumatic Trailer Bolo with Seedpod Plumb Bobs,” 2023. Hannah Reynoso Toussaint, “Genderless Bolo,” 2023. Jodi Webster, “It Will Always Be Skunk Hill,” 2023. Photo: Dasha Wright.

When I first learned that the art gallery connected to my alma mater, the University of North Texas, was hosting an exhibition consisting entirely of contemporary bolo ties, I was immediately intrigued. As a child born and raised in Texas, I always thought the boring accessory — which could only consist of a leather shoelace-like band connected by a small brown pendant — belonged to old, southern men with bad taste. Or Clint Eastwood. Or John Travolta in Pulp Fiction. However, more recently I’ve noticed more people, particularly within the younger generation, wearing them both formally and casually. Their resurgence baffled me, as did the fact that when I thought about it, I knew nothing about the neckwear or its origins.

So where did bolo ties come from? Noting a surprisingly bare Wikipedia page, I was pleased to find that the exhibition, titled Everybody’s Bolos, had a substantial amount of research at its foundation. The show was co-organized and co-curated by Ana M. Lopez, professor of Studio Art: Metalsmithing and Jewelry at the University of North Texas; Brian Fleetwood, assistant professor of studio art at the Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and citizen of the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma; and Hannah Toussaint, metalsmith and craft artist, UNT alum and current MFA candidate at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

Teresa Faris, “CWaB: Place #6,” 2023, recycled silver, reclaimed Comfy Perch, wood carved by a bird, wool, Thulite, 22.5 x 3.25 x .75 inches. Photo: Dasha Wright.

In Lopez’s essay accompanying the exhibition, she attempts to define and trace the bolo tie (also known as bola ties, bootlace ties, string ties, and gaucho ties) back to its prototype. The design typically features a cord held together at the throat by a decorative ornament, functioning at the intersection of a necktie and a necklace. Lopez traces its history back to neck wraps worn by Croatian soldiers in the seventeenth century, which were later adopted by French officers following the Thirty Years’ War. Decorative scarves and chains became popular in the Victorian era, worn by both men and women alike. During this time in the southwestern United States, neckerchiefs also grew in popularity. Additionally, scarf slides, a ring or tube that gathered the fabric ends together, replaced tying the scarf into a knot.

It isn’t entirely clear when the scarf transitioned into a leather cord, thus birthing the iconic bolo tie we know today. It wasn’t until the 1940s that the form was established and a commercial market was born. In the 1950s and 60s, following the popularization of Western movies and television series, bolo ties became a common sight in the Southwest. The neckwear is also regularly associated with Native craftspeople, as the decorative feature for the bolo often consists of turquoise, which is mined in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico.

In Fleetwood’s essay for the show, he discusses the bolo tie in terms of material culture, looking at its contemporary standings with Indigenous culture, cowboy culture, and queer and drag culture. Not only is the item worn prevalently in Indigenous and Hispanic cultures, but it is also worn by conservative politicians and wealthy elites. “Despite its relative youth, or perhaps because of it, the bolo tie exists at a strange, important, and contentious place within the history, culture, and politics of America,” he writes. “This position also makes the bolo tie an unexpectedly rich form, brimming with potential.”

J Taran Diamond, “Pavement Princess,” 2023, braiding hair, dyed silicone, anodized titanium, cultured freshwater pearls, thread, 20.5 x 2.25 x .5 inches. Photo: Dasha Wright.

In Toussaint’s essay, she explores her personal connotations with the bolo tie as a hyper-masculine jewelry prop within the heteronormative West. But, as many of us come to find out as we grow older, the Southwest has historically functioned as a secret refuge for queer people. Cowboys were not as racially homogeneous as they may have been depicted in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), amongst other iconic Western films. The bolo tie’s close association with the West is, in the same sense, indicative of its history within marginalized communities. As we continue to recontextualize history, new meanings behind objects emerge. Despite its stereotypical connotations, in contemporary culture the bolo tie has been reclaimed as a gender-neutral form of adornment, often worn by the queer community.

It was the lack of information and also the surprising ambiguity and fluidity of the bolo tie that spurred the three artists and scholars to come together to create an exhibition composed entirely of contemporary reimaginings of the accessory. Everybody’s Bolos features 30 contemporary artists showcasing their rendering of the bolo tie. Each artist approached the reimagining of the accessory from a unique angle, resulting in an exhibition impressive both in its craftsmanship and conceptual range.

Sulo Bee, “$P4CE✩彡C0W[bb]_DR3AMZ,” 2023, steel, silver, copper, maple wood, rubber, epoxy, geode crystals, 20 x 5 x .5 inches. Photo: Dasha Wright.

Sean Eren, “Carapace,” 2023, sterling silver, olive wood, stainless steel, aluminum, oil-impregnated bronze, chrome-tanned leather, 16.5 x 2.25 x .75 inches. Photo: Dasha Wright.

Sean Eren’s bolo tie, titled Carapace, references the hard outer shell or exoskeleton that forms on many creatures, such as turtles, crabs, and prawns. He uses the shell as an entry point to explore the layered nature of identity and the duality of individuals. Although the piece appears initially as sleek and elegant on the surface, underneath the exterior layer there lies “a cluster of intricate mechanisms and interconnected components,” much like the inner workings of a living body. Both the interior and exterior exist in a mutualistic relationship. “This dynamic reflects the inherent tension between interpretation and self-perception: neither offers a complete picture of our complexity, but considering both together offers a new level of understanding,” says Eren.

Jerome Nakagawa, “Lightning,” 2023, sterling silver, overlay bolo tie with channel inlaid yellow and white jasper, blue turquoise, black jet gemstones, brown leather cord, cord tips adorned with sterling silver sheet, beads, and tufa cast lightning bolt satellites, 22.5 x 2.75 x 1 inches. Photo: Dasha Wright.

Jerome Nakagawa is a Navajo and Japanese silversmith based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. His bolo tie revolves around the phenomena of lightning as it pertains to both sides of his ethnicity. In Japanese culture, lightning signifies rain and crop fertility. Conversely, the deity of lightning, Raijin, is one of the most feared because of his unpredictable nature. In traditional Navajo culture, lightning is the physical contact between Mother Earth and Father Sky — it is the initiator of life. The Navajo people (known as the Diné) believe there are four types of lightning: white and yellow (lightning within the atmosphere) and black and blue (lightning on or in the earth). “My jewelry artwork explores the cultural liminality associated with my experience of being a Diné and Japanese artist,” says Nakagawa.

The ornamental clasp of his bolo tie features the Japanese Kamon symbol for lightning, whereas the back side utilizes a Navajo-inspired weaving pattern depicting lightning and the silver cord tips include a Diné-style bead adorned with jagged channel inlay turquoise and jet gemstones. Nakagawa’s take on the bolo tie encompasses the contradicting meanings of lightning within the folklore of his heritage.

Left to right: Vanessa Miller, “Let the Overflow be Enough,” 2023. Jillian Moore, “Mons Bola,” 2023. James Thurman, “Memento Mori Bolo,” 2023. Wyatt Nestor-Pasicznyk, “A Wilder Blue,” 2023. Ger Xiong/Ntxawg Xyooj, “Re/search,” 2023. Photo: Dasha Wright.

At the end of the day, the accessory dodges any simple categorization or identity. Bolo ties are masculine. Bolo ties are queer. Bolo ties are Western. Bolo ties are Indigenous. They are kitschy. Camp. Traditional. Trendy. Truly, they are adornments belonging to everybody.

Ana M. Lopez says it best in her essay: “It is an object type that exists between a necklace and a necktie. It is made by jewelers but not discussed as jewelry. It is affiliated with indigenous peoples but is not an element of their traditional dress. The liminality of the bolo tie is part of what makes it such an interesting topic to explore.”

Everybody’s Bolosis on view at the University of North Texas’ CVAD gallery through May 10, 2024. The exhibition will then travel to Brockton, Massachusetts, where it will be on view at the Fuller Craft Museum from January 25 to June 7, 2025, and then to Hecho a Mano Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, from July 4 to July 28, 2025.

Emma S. Ahmad is an art historian and writer based in Dallas, Texas.

1 comment

I recently visited Rockmount Ranchwear in Denver. The young man assisting me in picking out bolos suggested that it was the founder of Rockmount who invented the bolo…though, he offered no proof. So I enjoyed reading your article to learn, perhaps, how illusive the origins are. Thank you.