There was more art-bashing by the Houston City Council this week.

Last month we reported on a council meeting where Ed Wilson’s project for the George R. Brown Convention Center was questioned, little more than a year after the Houston Arts Alliance muffed awarding Wilson his contract (it was awarded, then rescinded, then re-awarded). Why, Council Members mused angrily, were taxpayer dollars supporting an artwork about… birds?

This week, the Quality of Life committee (a sub-group of the council) called Debbie McNulty, the new Mayor’s Assistant for Cultural Affairs, onto the carpet about several issues relating to public art.

Council Member Greg Travis wanted to know why there has yet to be a formal evaluation of the civic art program, which was supposed to happen every five years, but has yet to occur even though the program is 10 years old? (McNulty’s response: “So we have a partial review, I would say.”)

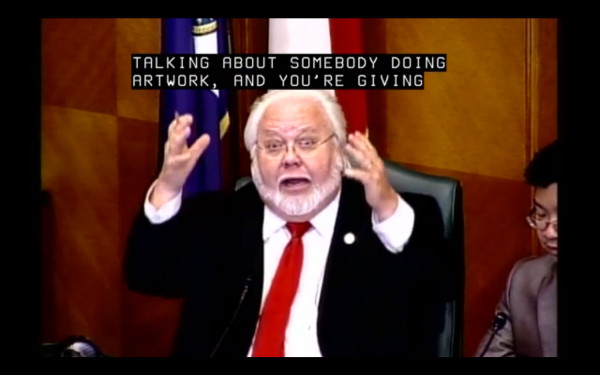

Council Member Michael Kubosh wanted to know how you can determine the value of art, when the raw materials of an $830,000 piece might just “cook down” to 30 or 40 thousand dollars? “Who appraises this?” he fumed. (Oh, Council Member Kubosh, we see the prices at international art auctions and we feel your bewildered pain.)

Council Member Brenda Stardig wanted to know how are panelists being selected for these million-dollar expenditures? And then she got to the point: “Is this something we want to continue to do as a city? When we are under the gun to keep police and fire on the streets to protect our citizens? Or is this something we table? For a year or two? Or do we throttle it back?”

There it is, folks. Oil has tanked, we’re facing a pension crisis that’s been kicked down the road from one administration to another, and Houston’s City Council wants to get rid of public art, because that $4 million we’re planning to spend on public art this year is apparently the straw that will break the city’s $2.5 billion total budget.

People fight hard when the stakes are this low.

Public art in Houston that’s commissioned by the city (as opposed to art commissioned by individuals or companies) comes from what’s called a “percent for art” ordinance, wherein 1.75% of any public building project (with some exceptions, including roads) goes towards art for that project. Percent for art programs started during the Great Depression, when the Department of the Treasury dictated that one percent of public construction projects be dedicated to art and decoration (which is how we got all the great mural projects of the WPA).

Today, hundreds of cities across America have percent for art programs, and while they won’t fix everything that ails a city culturally (they don’t allow for temporary public installations, for instance, and they’re typically a nightmare for artists to deal with), they embrace the idea that cities should be thoughtful, visually interesting and beautiful places to live.

Of course, all of this is built on the backs of artists, who don’t get monthly salary payments like the bureaucrats arguing both sides at a meeting like this week’s. Artists are generally the last people consulted when it comes to public art.

So there was a rich irony when Council Member Greg Travis complained about the incestuousness of selection panels, saying, “I was wondering why do we have only artists on that panel when we could have civic leaders or somebody else that has a fresh perspective.”

The reality is that artists are lucky to have more than a token member of their tribe on a selection panel. Panels are mostly made up of curators, arts administrators, and (yes) civic leaders who have a connection to a given project. If there were more artists on these panels, the results would probably be better. When you want a good recommendation for a surgeon, you ask your doctor. You don’t ask the hospital administrator.

Then the committee complained about Houston Arts Alliance (HAA) receiving $170,000 to administer Ed Wilson’s $830,000 artwork (for a total project budget of $1 million). The number does sound big, but it’s worth noting that HAA’s fee is under 20% of the budget, which is the going rate for sourcing and managing a public art project—indeed, most artists are happy for a commissioning entity to take 20%, as opposed to the normal gallery cut of 50% of a sale. HAA has modeled its price on standard practices in the art industry; the problem is that the art industry (if one can call it that) is anything but standard, and when Council Members see a line item on a budget that HAA received $68,000 for overseeing the fabrication of Ed Wilson’s artwork, they tend to view that expense with a gimlet eye.

“What do we get for our $68,000 that we’re paying Houston Arts Alliance for fabrication? What do they do for their $68,000 specifically, within Mr. Wilson’s art piece?” – Council Member David Martin

“Well, specifically, oversee the artist to make sure his project is coming in on time and on budget.” – Debbie McNulty

“Wow, $68,000 to oversee an artist to figure it out… .” – Council Member Martin

Then Council Member Mike Laster, who is new to the Quality of Life committee, wondered how many employees HAA has. McNulty guessed 25, but said she wasn’t sure exactly. (She was close: according to HAA’s website, they currently have 24 employees.) Laster implied that number seems like a lot.

Is it a lot? We examined HAA’s annual reports from 2007 to 2015, and we found the following:

- In 2007, HAA had 13 staff members. Today they have 24. Which means staff size has increased 85%, but over the same period, HAA’s “management and general” expenses (which may or may not include all of those staff members) rose 223%. And its fundraising expense increased a whopping 606% in the same timeframe.

- Civic art and design revenues and expenses have remained fairly steady for HAA over the past seven years, although HAA consistently reports higher civic art expenses than revenues, which is odd. They’re losing money on civic art?

- Aside from managing civic art projects, HAA’s main function is administering the grants that are awarded to artists and arts organizations from the city’s hotel occupancy taxes (called HOT taxes). As a percentage of HAA’s HOT tax revenue, grants have decreased from a high of 93% in 2010, to just 73% in 2015 (and it was only 61% in 2014). Meaning a lot less money from the HAA HOT tax pool is being granted to artists and arts organizations than used to be. [Full disclosure: Glasstire is a grant recipient from HAA.]

Ironically, Houston arts organizations received an email on February 25th from HAA Director of Grants Richard Graber, about the need to tighten belts in this economy. Graber wrote, “HAA has already reduced its operating budget by 5%, and we would like to recommend that your organization plan for a similar reduction to your projected general operating grant for this fiscal year.” Of course, when your management and fundraising expenses have mushroomed as much as HAA’s have, it’s easy to talk about 5% reductions.

One final thought, back to the Quality of Life meeting:

During the meeting, Council Member Stardig commented, “To be made to feel that I don’t know culture and I’m not an artist and I don’t understand, that’s not what this is about. This is about money.”

Which sounds like she got her feelings hurt for being made to feel like a rube. And here is the heart of the problem with art: it takes years to get good at looking at it. The greatest art resonates with anybody, including Brenda Stardig, but that level of art is rare, and it doesn’t help that the art world can be an insular, snobbish place where people look down their noses at suburbanites who would rather go to a football game than go to a museum. Council Member Stardig is probably correct: she doesn’t know about culture, and she doesn’t understand. But even if she were patiently led to the water, would she be willing to take a drink?

Cities bother with supporting art because art is important, regardless of whether some Americans think it’s a frivolous waste of money. Art has been around for hundreds of thousands of years, because the act of looking at the world, and making an object or a story or a piece of music that resonates with people, is fundamental to our species. More to the point: artists are not crazy, and they’re not children, and the good ones certainly know how to put a responsible budget together (ahem, Council Member Martin), and how to deliver a project on time. And those skills are worth paying money for.

Or, as Council Member Ellen Cohen said:

“Having absolutely no artistic talent and not being able to evaluate it when I do look at it, I do have one analogy though—I know that sometimes, you know, I can go to my doctor with a problem and my doctor will take maybe 10 minutes—five minutes—to tell me what’s wrong. And then I get a bill for three hundred dollars. Three hundred dollars! For ten minutes! But I’m not paying the 300 for ten minutes. I’m paying for all the years he or she spent in medical school and so it’s not the $200 for whatever the birds are made of or how they’re being hung, it’s for the talent that this gentleman has generated over the years as an expert.”

It’s hard to say what the fallout will be from this particular meeting, but our prediction is that Houston City Council will be getting back to this subject again.

Robert Boyd provided additional research and reporting for this article.

5 comments

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is probably worth about $70- in raw materials.

I love Ellen Cohen. Can we clone her?

Knowing where to make the mark

________________________

“…Before long, the greatest scientific minds of the time were traveling to Schenectady to meet with the prolific ‘little giant’; anecdotal tales of these meetings are still told in engineering classes today. One appeared on the letters page of Life magazine in 1965, after the magazine had printed a story on Charles Proteus Steinmetz. Jack B. Scott wrote in to tell of his father’s encounter with the Wizard of Schenectady at Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant in Dearborn, Michigan.

Ford, whose electrical engineers couldn’t solve some problems they were having with a gigantic generator, called Steinmetz in to the plant. Upon arriving, Steinmetz rejected all assistance and asked only for a notebook, pencil and cot. According to Scott, Steinmetz listened to the generator and scribbled computations on the notepad for two straight days and nights. On the second night, he asked for a ladder, climbed up the generator and made a chalk mark on its side. Then he told Ford’s skeptical engineers to remove a plate at the mark and replace sixteen windings from the field coil. They did, and the generator performed to perfection.

Henry Ford was thrilled until he got an invoice from General Electric in the amount of $10,000. Ford acknowledged Steinmetz’s success but balked at the figure. He asked for an itemized bill.

Steinmetz, Scott wrote, responded personally to Ford’s request with the following:

Making chalk mark on generator $1.

Knowing where to make mark $9,999.

Ford paid the bill.”

————–

*excerpted from “Charles Proteus Steinmetz, the Wizard of Schenectady” – Gilbert King, Smithsonian Magazine, August 16, 2011

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/charles-proteus-steinmetz-the-wizard-of-schenectady-51912022/?no-ist

I wish the people speaking for our percent for arts in this city could muster up some kind of solid defense- at least answer a simple question correctly. Every person who has followed this knows that the budget is 830K.

They (the Council) are going to use their (HAA’s CEO and the new Cultural Office director) lack of understanding and piss-poor preparation as an opportunity to reduce our city’s art support, in turn, taking jobs away from the Houston art community’s next generation, and taking interesting public art from the people of Houston. We won’t know what hit us.

These guys have one job- be the liaison between the artist and the uneducated powers that be || and answer with some got’damn confidence.

where has all of the camaraderie gone? this is the time! the arts are being marginalized daily. studios are expensive, galleries are closing and public money is collecting dust for civic art commissions. artists, please assemble sooner than later. petty differences need to be put aside. the fake news commander in chief is in town and there is little protest, has everyone completely worn down? the creative community needs to remember the influence you have over positive change. WE can’t win on the national level if we are not making an effort on the local