Many people are joyfully celebrating (and others bewailing) yesterday’s Supreme Court ruling upholding gay marriage, which will overturn the shameful 2005 amendment to the Texas state constitution that banned it. Many others watched President Obama’s moving eulogy for Clementa Pinckney yesterday, who was killed last week in Charleston. Here are some scattered observations about our state, inspired by a remarkable week of news.

1. SCOTUS and us

Texas was part of the Confederacy. That legacy is still all around us, in visible symbols and invisible attitudes and prejudices. And these days, although we may not consider ourselves “Southern,” Texas is far more independent-minded than any other former Confederate state. You can’t imagine the governors of Mississippi or Alabama hinting at their states seceding, as our last governor did. (Though granted, that was before he started wearing glasses).

“When we came in the union in 1845, one of the issues was that we would be able to leave if we decided to do that.” In fact, that’s not true. And yet people in Texas voted for this guy.

Although we fancy ourselves iconoclasts who champion the rights of the individual, that’s not always the case. Until 2003, Texas still had a sodomy law on the books. Our state embarrassingly upheld the law when challenged, even though it applied to people in the privacy of their own homes. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which struck down the law 6-3 in Lawrence v. Texas. (And yes, one of the three dissenters was Antonin Scalia, who called the majority’s decision part of the “so-called homosexual agenda.”)

On the other side of the progressive coin, Texas is also trampling the rights of the individual by being one of three former Confederate states that does not offer a license plate with the Confederate battle flag on it (the others are Florida and Arkansas; Maryland also does). Last week the Supreme Court upheld Texas’ right to refuse to offer the plates. The Texas DMV said “A significant portion of the public associates the Confederate flag with organizations advocating expressions of hate.”

All of which is to say: states’ rights cut both ways.

2. On symbols

When I was a kid, there was a restaurant in Houston called the Confederate House. The décor was antebellum, with painted murals of plantations and oval portraits of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis in the entry, and—yes—African-American wait staff serving “Confederate Fried Ribeye Steak” to the wholly white clientele. Remarkably, decades after anyone I knew would consider going there (and after a patron was shot outside the restaurant—though good luck finding that story online), the place closed in 2001.

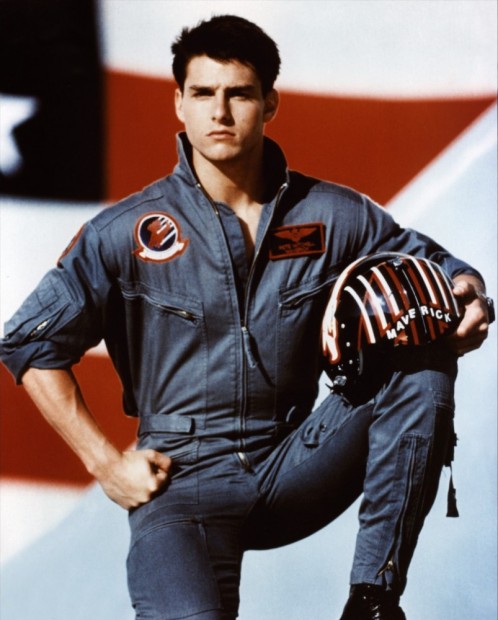

The Confederate House seems hard to believe now, but so does the fact that the mascot of my high school was the Johnny Reb. With battle flag. As seniors, my class (which elected the first black student body president in the school’s history) led a successful petition to change the mascot. I remember when we were signing it, my homeroom teacher, who was British, looked at us seriously and said: “You know what the right thing to do is.” Our petition was overruled by the alumni. But the mascot was finally changed 14 years later, to the Mavericks.

This week, the Confederate battle flag has been making the news, and no doubt thousands of people who didn’t realize that the battle flag was not the official flag of the Confederacy have figured that out. The official flag of the Confederacy, a.k.a. the stars and bars, can be seen at many state parks in Texas, as part of the Six Flags. These are the flags that have flown over Texas in its history, and as any Texas schoolchild can tell you, they are: Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the Confederacy, and the United States. It’s worth noting that every one of these flags’ governments permitted slavery at the time they flew over Texas, until the end of the Civil War, when the US Flag was reinstated over the capitol in Austin, a full six months before ratification of the 13th Amendment.

Supporters of the Confederate battle flag point out that the flag itself doesn’t cause people to massacre other people in a church, which of course is true. But symbols, by their nature, are weighted with meaning; and while outlawing them invests them with power, so does condoning them by displaying them on government property. Just because Cooter from the Dukes of Hazzard would have us believe that the battle flag represents “Grandpappy” rather than slavery and white supremacy doesn’t make it so.

Put another way: there’s a reason Londoners who survived the Blitz were pissed off when Prince Harry wore a Nazi uniform to a costume party.

3. On statues

There’s a beautiful statue in Houston’s Sam Houston Park titled Spirit of the Confederacy. Should we remove this lovely statue (with its admittedly rather comical palm-frond-of-modesty), because its title is another way of saying “Spirit of Armed Insurrection and Legalized Enslavement?” I hope not, but its presence reminds us of a legacy some of us would rather forget.

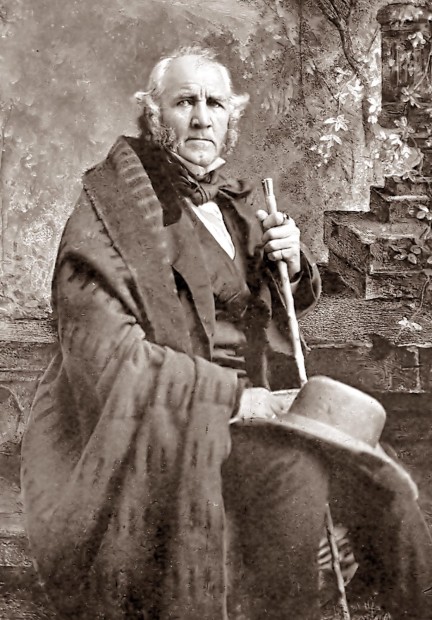

Sam Houston was governor of Texas when the Civil War broke out. When the Texas Legislature voted to secede and join the Confederacy in 1861, Houston strongly opposed it. He was then forcibly removed from office for refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy, saying “I deny the power of this Convention to speak for Texas.”

Houston also correctly predicted that the South would lose the war. Sadly, he didn’t live to see his vindication.

It’s easy to admire Sam Houston, a Unionist. But some people, particularly in the wake of the Charleston shootings, might argue that it’s neither possible nor advisable to have a nuanced view of people who fought for the Confederacy.

The University of Texas at Austin has statues of three Confederates: Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia; Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy; and Albert Sidney Johnston, a famous commander from the Texas Revolution who was killed at the terrible battle of Shiloh during the Civil War. Davis was an unrepentant slaveholder and white supremacist to his death in the 1880s. Lee was a slaveholder, but he acknowledged it was an evil institution and he freed his slaves in 1862 (although this was in accordance with his father-in-law’s will). Johnston, like 95% of Confederate soldiers, never owned any slaves, although he might have aspired to.

This week, following killings of nine people at a historic black church in Charleston, SC, the graffiti “Black Lives Matter” was painted on the three statues. I imagine most students weren’t aware of their existence before then (as a graduate student at UT in the mid-90s, I didn’t know they were there). Should the statues be removed, perhaps to the Texas History Museum on MLK Boulevard? I would argue that Davis for sure, and possibly Lee, should go. But what about Johnston? Does his fighting for the Confederacy trump his fighting in the Texas Revolution? By all accounts he was a brave and decent individual, who stayed at his US Army post in California after resigning to join the Confederacy, so that his replacement could arrive—even though this delay meant a dangerous summer crossing of the southwestern desert.

Although I don’t believe this, there is a compelling argument to be made that Johnston’s memory should be allowed to disappear, as the memories of millions of slaves before him were allowed to disappear. In a famous letter to the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass said, “when I remember that with the waters of [America’s] noblest rivers, the tears of my brethren are borne to the ocean, disregarded and forgotten… I am filled with unutterable loathing.”

(l): Albert Sidney Johnston’s tomb in the Texas State Cemetery in Austin, Texas. (r): Round Rock, TX slave cemetery

4. On monuments

I visit the San Jacinto Monument about once a year. Today it’s located amid smelly refineries, but this is the place where the the Texian army defeated the Mexican General Santa Anna, resulting in Texas’ independence from Mexico. It’s a remarkable monument, not small of course (purposefully designed to be 15 feet taller than the Washington Monument, YEEHAW!). I highly recommend visiting. The inscription on it gets a bit purplish:

With the battle cry, “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” the Texans charged… The slaughter was appalling, victory complete, and Texas free! On the following day General Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna, self-styled “Napoleon of the West,” received from a generous foe the mercy he had denied Travis at the Alamo and Fannin at Goliad…

Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican–American War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American Nation, nearly a million square miles of territory, changed sovereignty.

In other words: you’re welcome, California.

Like many people here, I love Texas. But sometimes it can be a difficult place to love. It has a troubled past, and symbols of that past are everywhere. It also has a troubled present, and it’s easy to forget that when you live in the art-world bubble of one of its large cities. Houston has a gay mayor. Arlington does not.

But perhaps part of the reason we love Texas is that it’s not really the South, and it’s not really the West. It’s both, but also something unique. Part of its contradictions are explained by sheer scale: there’s a huge difference, culturally and geographically, between people who live in the piney woods of East Texas, and people who live in rugged, vast West Texas. True, there are people here in living memory who would drag a man behind a truck to his death because of his race. And today there are heavily armed, self-appointed “freedom defenders” with itchy trigger fingers along the border. But there are also activists working to improve the lives of minorities. And now there are gay Texans joyfully planning weddings.

And most importantly, for me anyway: there are artists. Their work makes us attentive to it all.

Featured image: Gustave Courbet, Le Sommeil, 1866. Collection of Le Petit Palais, Paris.

6 comments

I did an article on the San Jacinto battle and monument several years ago, and my favorite factoid I stumbled upon was that one of the Texian combatants, John M. Allen, had been a friend of Lord Byron and was with the poet when he died in 1824. Though not one of the Allen bros who founded Houston, this Allen was first mayor of Galveston.

Of all the sources consulted, the only one that noted the Byron connection was a book by Frank Tolbert’s father.

Treason, is trendy. Advocates of slavery murdered at the Alamo. Spurs lost—now that’s a tragedy.

Sam Houston withdrew from government choosing not to be part of the Confederacy, He, in no way supported the Confederacy. He supported Women’s Rights early on. Upon burial he was unpopular but history has proved him in the right.

Sam Houston was “cool” before “cool” was cool.

Rosanne Friedman

Great article, Rainey. There’s fortunately a good number of excellent historians doing work in the areas you’ve covered here, particularly re: Texas exceptionalism and the question of a southern or western identity. Ty Cashion is a good place to start for folks wanting to know more. There are a few articles and transcribed talks of his out there (look in JStor) and he has a book coming out in about a year from UT Press called “Lone Star Mind.” Richard R. Flores’ “Remembering the Alamo,” Glen Ely’s “Where the West Begins,” Laura Lyons McLemore’s “Inventing Texas” are all excellent and available now.

Oh and BTW, Mexico outlawed slavery in 1810, so under Mexico, Texas was technically a non-slave state (Coahuila y Tejas), although this was of course was a major point of contention between Texians and the Mexican government and it was not effectively enforced.

Ah–I had assumed that since there were slaveholders in Texas under Mexico, it was approved, at least tacitly. Good to know.

Thanks for the book recommendations!

Rainey,

You really need to be more informed about the issue of slavery in Texas. I think the book you really need to read is:

Campbell, Randolph B. An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.