Monuments are having a moment.

For millennia, monuments have been contested as artifacts of power, privilege, and community, because objects from the past have the capacity to shape present lives and offer visions for the future. However, in recent years, America’s public monuments — of which there are thousands spread across the United States — have come under intense debate and public scrutiny.

Public monuments are significant because they offer a material narrative for interpreting public space and, true or not, offer a literal concrete mythos and narrative to a community. Public monuments can serve to keep people out of a community and bring them together. “Monuments aren’t history lessons,” art historian Erin L. Thompson declares in the introduction to her new book, Smashing Statues: The Rise And Fall of America’s Public Monuments, “they’re pledges of allegiance.”

Recent debates about American’s public monuments were catalyzed in May 2020 when George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer. Floyd’s murder immediately sparked protests against police brutality and systemic racism in hundreds of American cities. Inexorably tied to these protests were heated debates about the role of public monuments, especially as America’s monuments are often explicitly or implicitly tied to white supremacy. Incidentally, something like 170 public monuments fell or were removed in the year after the protests began.

In Smashing Statues, Thompson explores the history of the tempestuous and — very often — ironic relationship the American public has with its public monuments, from the Stone Mountain Confederate Monument to the toppling of a statue of Christopher Columbus at the Minnesota State Capitol. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Lydia Pyne: This is a fascinating and, of course, timely topic here in 2022. Can you tell me how you became interested in writing a book about public monuments?

Erin Thompson: As an art historian, I know there is a big difference between an ideal and the messy reality behind public monuments. This has been true for any number of groups throughout history. More often than not, monuments are put up by people rich enough to pay for them and powerful enough to give them a space in public. What really sparked the idea for this book was when I tweeted about a video of a statue of Columbus being toppled in St. Paul, Minnesota.

LP: I remember that tweet. It went viral.

ET: Exactly. I was denounced by various, more conservative media as someone teaching my students to topple monuments, which I definitely do not do. Tucker Carlson said that I lead armies of nihilists. The only nihilists I know are my kids and they don’t even listen to me about bedtimes. But in the viral twitter thread, there were thousands of comments and questions and I realized that there’s so much that people don’t know about monuments that I could provide answers to. So this book is definitely not about solutions, but it’s about context — information and stories around monuments to inform what we want from them going forward.

LP: One of my favorite things about writing nonfiction is coming across stories that make me think, “How did I not know this before?!” Was there a similar moment for you with this book? Was there a story that was just bizarrely unexpected?

ET: Yes, definitely. As I say in the book, monuments are our nation’s selfies. But they are there to make you stop asking questions. But just like any time you have money and debates about the use of public space, you’re going to have some wild stories. And I found a lot.

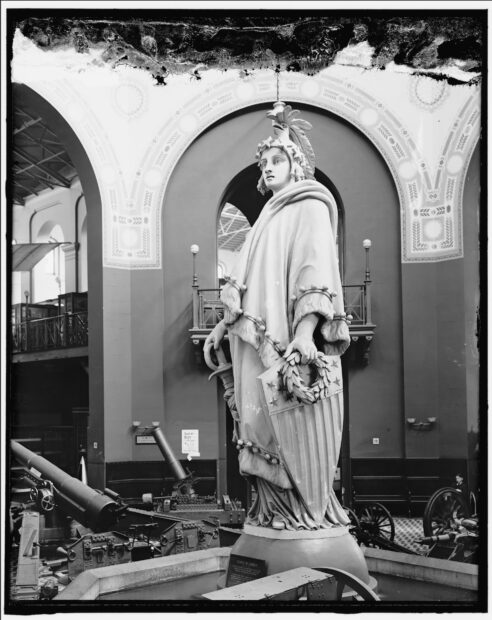

Plaster model used by Philip Reed and Clark Mills to cast the bronze statue of “Freedom” installed on the U.S. Capitol Building in 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-H25-3200A

LP: This feels like a perfect segue for us to talk about Stone Mountain.

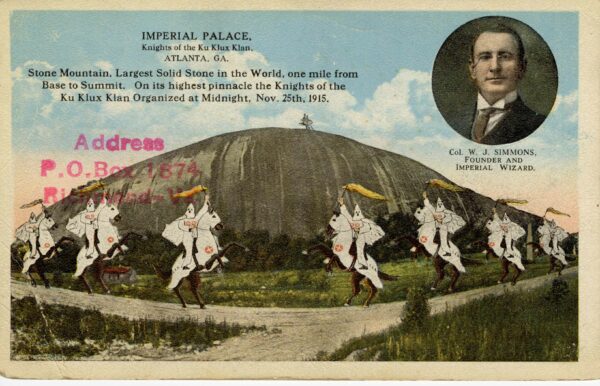

ET: Right. So people started to argue about Stone Mountain in the comments of my 2020 tweet, saying that it’s a monument to white supremacy, but it’s too bad that there isn’t a way to remove it.

LP: Because of its size?

ET: Yes, Stone Mountain is a giant carving on a mountain outside of Atlanta, Georgia. The motivation for the carving started as the vision of a Confederate widow who wanted a bust of Lee carved into the mountain. The widow asked a New York city sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, to carve it. And he convinced her that just the head of Lee alone would look insignificant, so he upselled her to a vision of more than 700 figures sweeping across the mountain at least 30 feet tall.

Ultimately, Stone Mountain ended up being Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis riding horses — it’s actually the largest bas relief carving in the world. It started as a project in the 1920s and what we see now was finished only in the mid-70s. I also found out during my research the first head of Lee carved in the mountain was in fact blown off the mountain in 1924.

LP: I didn’t know that.

ET: Borglum also signed a contract where he got a percentage of all of the money spent on the mountain. So the more he carved, the more he made. He worked extremely slowly in part because in the beginning he had no idea how to carve the mountain. He joined the Ku Klux Klan to get along with the people running the project. A lot of the funds that were raised for Stone Mountain keep disappearing; Borglum was notorious for borrowing money that he had no intent of returning and seemed to be telling his creditors that he’d pay them back with the proceeds from this commission.

Postcard Celebrating the 1915 revival of the Klan at Stone Mountain. (Courtesy Virginia Commonwealth Libraries.)

LP: The Borglum aspect to the Stone Mountain story is truly bizarre.

ET: There’s more to the monument’s story, though. I came across just a mention in a book about Stone Mountain of prison inmates who helped work on the park starting in the fifties. Then I did a lot more research into newspaper archives and by sending Georgia Freedom of Information requests and found from the fifties to the nineties, the park itself was home to a prison unit, which housed inmates who had to work there. They were expected to create the park, do the landscaping, build park buildings, and then to maintain it. So it’s been a public park since the fifties, but the economics of that only worked because of this free labor force.

So what completely blew my mind was thinking about some of the earlier inmates who had life sentences. So what would the experience have been like for a Black Georgian expecting to spend the rest of their life within a park dedicated to the Confederacy?Those are the types of histories that are hidden by the easy stories we tell about monuments, and those are the histories we need to think about when we’re making decisions about what monuments should continue or how they should change.

LP: Often debates about public monuments — and whether we ought to leave them up, take them down, better contextualize them — descend into debates about the character of the person featured in the monument. Does your approach to thinking about monuments move away from that?

ET: I want to ask, Why did the monument go up in this form, in this community at the time? What did people say during dedication speeches about why they wanted it there? How did people react to it? Debates about the person’s character are important, of course, but there are other aspects to the monument.

LP: I keep coming back to the idea that monuments are these physical, tangible, material objects. How does that influence the logistics of them going up or coming down?

ET: It was really surprising to me to learn how monuments are really nailed to their pedestals. For example, how many laws exist to keep what’s there, there. Even in states or jurisdictions without these specific protection laws for monuments, there doesn’t exist any procedure for questioning a monument. So it’s not surprising to me that protests have turned more physical regarding removal. Many of the protestors that I talked to tried for decades to get their objections to monuments heard with absolutely no results.

LP: And after a statue or monument is removed?

ET: People assume that removing a statue from its pedestal is the hardest part. But actually, what happens next can be hugely complicated and can be really rewarding, or it can be really expensive and result in no one being happy. Many people say, “why don’t you just put it in a museum where we can see it as an artifact, but without it being in a public space?” But museums aren’t perfect solutions — they’re also places of power with complicated histories and legacies.

LP: They’re still places where people go to look at objects that are valued in some way.

ET: There are a couple of statues that are being transformed by artists into something else that will keep the memory of the oppressive role that these statues have played, but also make them into an expression of a different future. That takes a lot of funds and time for community conversations and is derailed at so many points.

LP: What do you hope readers take away from your book?

ET: I think everybody has and should have a voice in saying what they want public art in their community to look like. That’s the most important thing. I hope that the other takeaway is that it’s really fun to research the history of a monument, and you will uncover all sorts of things that you would never have imagined. So get going! Because there are thousands and thousands of monuments across America that probably need some questioning.

Smashing Statues: The Rise And Fall of America’s Public Monuments is published by W. W. Norton & Company. It will be released on February 8, 2022.

1 comment

so, now art is not art?