Over the past week, as I sat down several times to write about Bill, I began to discover that I don’t really know all that much about him. Most of what I learned from him was gained by observation, by watching his behavior in different circumstances. I came to the conclusion that although I knew him in a certain and, for me, important way, I did not know him on a deeply personal level. I was about 27 when I began showing at Moody Gallery, and I think Bill must have already been in his early 70s. With such a great age difference there is naturally a kind of distance between the hubris of youth and the more comprehensive understanding of life that comes to some people in old age. And so I watched him, occasionally joked with him and, more rarely, we exchanged a few words about his work or mine.

In the absence of a deeper knowledge of his biography, I asked myself what Bill’s greatest lesson to me was. The answer was how to die. There are two kinds of death I think: fast and slow. My father died quickly, suddenly and unexpectedly. That kind of death has its own lessons for those left behind in what is essentially an abduction. Bill died slowly, declining over a period of several years, with the last year spent in a much-diminished physical condition. The main culprit in his death was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but in his last years he also experienced the thousand other physical indignities that come with a gradual decline.

Death from a failure of the lungs is not unlike death from a failure of the heart. The heart and the lungs are inextricably linked in the process of breathing, without which there is no life. But they are also linked poetically. One is said to fall in love as a consequence of the actions of the heart and often, as the cliché goes, when one falls in love, their breath is taken away. We are lucky if we feel this poetic shortness of breath once in our lives, but we will all someday experience the physical failure of breath as a consequence of the failure of the heart. That slow but inevitable suffocation that rose up in me with the failure of my own circulatory system due to a diseased heart shadowed Bill’s increasing breathlessness during the years I knew him.

I never saw the parallel quite as clearly as I do now, but I recognized in a more intangible way that Bill and I were sharing the same road on the way to the same destination. Medical science intervened on my behalf in the form of a heart transplant. Otherwise, it is possible and indeed likely that Bill would have outlived me. Because of this unnatural intervention I am able to look back and watch myself die in retrospect. I did not suffer the failure of my heart gracefully. My friends and family and especially my wife experienced great pain as a consequence of my violent refusal to accept or make peace with the limitations and indignities of a death sentence that I am now serving on probation. I will never reach the 82 years Bill filled with sculpture, jewelry and architecture, but in spite of this knowledge and perhaps because of it I still view death as something to be fought and rebelled against.

Bill however, has set before me a last terrifying example and challenge: to overcome my rage and fear and to someday die with as much grace and dignity as he did. He did not rage, he did not collapse with fear and although he surely experienced great frustration and anger, he consciously accepted that he was dying. He was tireless in keeping himself at the limit of his physical capabilities. He used a walker and moved through the gallery. He and Betty continued to travel to their home outside of Houston, which Bill designed and built after a heart attack. I have seen sick people stubbornly refuse the many compromises illness and old age demand and sink into depression and immobility. He was wise enough to philosophically submit to the reality that raging against death will not alter its advance.

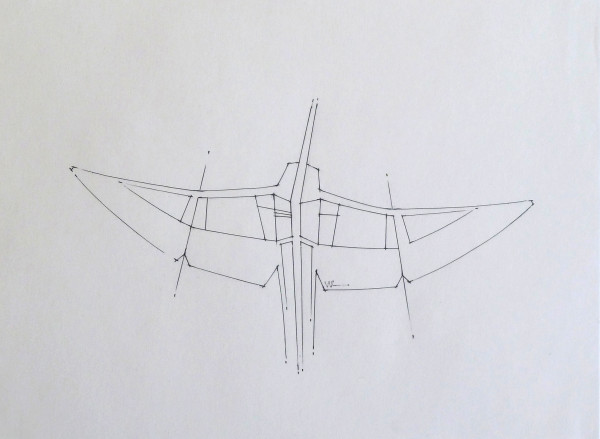

Bill Steffy, Untitled, (2006) graphite on paper, 9″ x 13 3/4″ Courtesy of Moody Gallery, Houston, Texas

The great tragedy is that in his last years, Bill’s hands shook too much to make his work anymore. So we are deprived of Bill Steffy’s late works, works that would have been a final translation into form of the experience of his life and death. I know this was the most unbearable of illness’s indignities toward him. Despite the fact that Bill was unable to make objects, he never quit working. Betty told me that one day she walked into their apartment and, seeing Bill staring into the skylight above the bed where he was forced to spend so much time, asked him what he was doing. “I’m examining textures,” he replied.

One day, when I walked up the driveway to the back door of the gallery, I encountered him in his wheelchair looking into the leaves of a tree next to the porch. We exchanged some words, I went inside and turning to look back through the glass door saw that he was carefully watching a bird. At that moment I thought of his many elegant, spare architectural renderings of birds and I understood that although we will never see evidence of it, Bill worked to the end.

5 comments

Dear Michael,

What an eloquent and elegant tribute you have written for Bill!

Yours truly,

Sandy Parkerson

Such thoughtful observation. Thank you for your beautiful words, Michael.

thank you Michael What a lovely remembrance.

Thank you for writing so eloquently about Bill Steffy! I am in Tulsa today sitting in a hospital room at the bedside of my uncle who has congestive heart failure and pneumonia ……. and these life and death issues are on mind today. I found your words comforting!

beautiful