Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere,” 2002, mixed media installation at McNay Art Museum. Unless otherwise noted, all works are courtesy of the artists & Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The first solo exhibition by the sculptors Einar (b. 1963) and Jamex (b. 1960) de la Torre in San Antonio, de la Torre Brothers: Upward Mobility, squarely confronts our current age of avarice, violence, dangerous over-consumption, and ecological degradation. One salutary highlight is the enormous and complex installation Le Point de Bascule (the Tipping Point), a maelstrom of excess. It is a ruin – not an archaeological ruin from an earlier age, but an eerily and hastily depopulated ruin that symbolizes our present. It’s not Nietzche’s Twilight of the Idols, but rather the Twilight of the Oligarchs. As we shall see, however, Le Point de Bascule is intended as a more general condemnation of affluence and consumption, one with consequences likely to be ruinous for the entire world and all of its inhabitants.

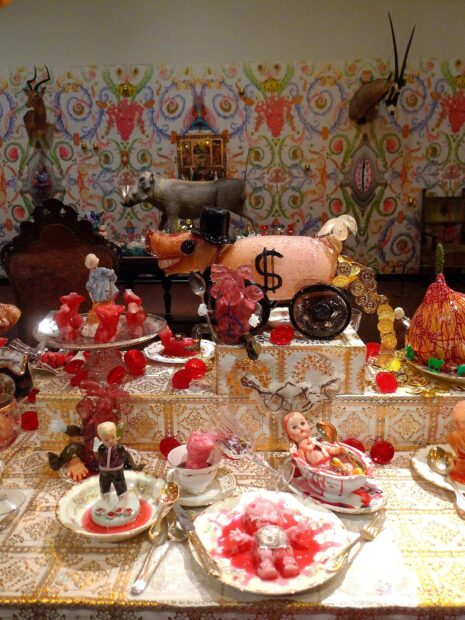

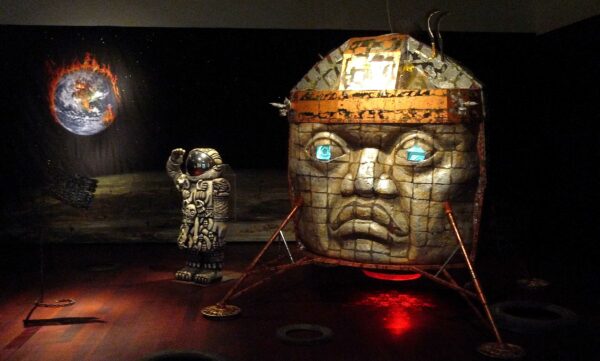

Upward Mobility is divided into four sections: the first features hand-blown glass sculptures and lenticular prints; the second is Le Point de Bascule (2024), an immersive installation with an astounding banquet table as a centerpiece; the third section features two large-scale lenticular pictures that shine like hellish altarpieces in a darkened cathedral; the final room is a stage for Colonial Atmosphere (2002), a retro-futuristic reimagining of the moon landing — and the moon’s colonization — dominated by Olmec and Aztec sculptural imagery. For a quick tour of the exhibition, see the video linked here.

The de la Torre brothers are sculptors who began as glass-blowing artists. Born in Mexico and educated in the U.S. (their family moved to California in 1972), the brothers currently work on both sides of the border in Baja California and San Diego. For an overview of the artists’ careers, see my Glasstire review “‘The Cheech Center’ for Chicano Art is Brilliantly Inaugurated by the de la Torre Brothers’ Collidoscope.”

Art glass is usually associated with decorative or utilitarian work that is primarily aesthetic in nature, so it defies expectations that artists who trained in the medium of glass would be taking on the biggest political issues of the day, but that is precisely the kind of subject matter that the de la Torre brothers have chosen to address.

Glass Sculptures and Lenticular Prints

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Upward Mobility” exhibition installation shot. Photo: Paul Feuerbacher, courtesy of the McNay Art Museum.

The brothers first made their names as glass artists with sculptures such as the ones in the first gallery at the McNay. Several of them utilize appropriated material, including the remarkable El Drugstronauta (2012) (see the “Collidoscope” review that is linked above).

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Mi Chicano Corazón,” 2023, blown glass and mixed media, 40 x 20 x 16 inches. Photo: Philip Ritterman.

Mi Chicano Corazón features a prickly pear cactus that is growing out of a human heart. According to Aztec myth, the prickly pear cactus originated from the heart of Copilli, who made the mistake of opposing Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec patron god. Huitzilopochtli ripped out Copilli’s heart and threw it into Lake Texcoco. The cactus that sprouted from this heart in turn bears red fruit that symbolizes human hearts.

Einar explains that Mi Chicano Corazón “is our answer to [the question] ‘are you guys Chicano?’”

“Of course the answer is yes,” he adds, “although we did not grow up in a Chicano environment.” Chicano culture is rooted in Mexican culture, and the de la Torre brothers are here utilizing a core myth from the best-known indigenous Mexican civilization.

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Mi Chicano Corazón” (detail), 2023, blown glass and mixed media, 40 x 20 x 16 inches. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the above detail, one can see that the heart is sprouting out of a wire hubcap housed within a rim, which serves as a shiny metal plant pot. This automotive imagery references lowriders and lowriding, which are important aspects of Chicano culture, as well as much beloved subjects utilized by the de la Torres (for other examples, see Mictlanteputin and Colonial Atmosphere, as well as the discussion of Gaiatlicue in the “Collidoscope” review).

“We have all of the [Chicano] layered symbols in our work, and the use of iconography and color,” explains Einar.

In the bottom section of Mi Chicano Corazón, one can see that the hubcap that brings life to the Chicano heart is divided into nine framing devices made of polished aluminum. Each of these features a hypersexualized nude torso; they are alternately male and female. The males are hypermuscular and the females are hyper-voluptuous. They refer to the sexualized aspects of car culture, and the mating rituals that surround it. Because glitz and glamor are part and parcel of lowrider culture, each of these orange torsos is framed by decorative strands of pearl-like flowers, topped by an enormous, faux gem.

Einar refers to these small torsos as “beautiful figures, attractive figures, ones that invoke fertility.” Einar views beauty as nature’s way of ensuring fertility and reproduction. So these tiny torsos are a way of “grounding” the piece, because, just as “wheels go round,” the mating rituals associated with low-rider culture are “part of the cycle of life.” Thus the literal wheel also represents the wheel of life. The product of that cycle is represented by the pregnant female torso. The brothers did not intend for the nine panels to represent the nine-month gestation period of a human pregnancy, but that number is serendipitously symbolic.

With respect to Chicano culture, Einar notes: “Culture is different when you are born into a culture, then when you are first or second generation.” He refers to himself and his brother as “phantom limbs” and avers: “we are not going to be defined by this or that [definition].” He liked the analogy I made of them as grafted, hearty nopal paddles. In this sense, he says they are “both prickly and succulent,” as they thrive on both sides of the border.

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Birth of Modern Medicine,” 2023, blown glass and mixed media. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Some works in the first section have very pointed political content, such as the Birth of Modern Medicine, which features a white male’s head being birthed out of what looks like a skull-headed dog’s ass. This creature is actually what indigenous people refer to as a nahual, a shapeshifting animal spirit. The modern, Western doctor thus emerges from a symbol of ancient indigenous culture. “Where would medicine be without the cultures that come before it?” asks Einar. “Modern medicine is built on them.”

This appropriated head comes from a medical mannequin that doctors utilize in their offices for patients to locate aliments. The brothers had already used the mannequin’s torso in another piece.

The large sets of dice refer to the element of chance in health, diagnosis of illnesses, and life in general. So, too, do the Mahjong chips beneath them. Einar emphasizes that though one is dealt a hand in life, one also “has to play the game.” In this sense, even “fate gives you choice,” to be “a victim of the cards you are dealt, or to make the best of that hand.”

A recumbent female nude made of yellow glass lays beneath the nahual. Einar refers to it as “a beautiful figure, a Maja figure,” as in Goya’s Naked Maja (c. 1795-1800). He also associates it with classical female fertility figures, such as Venus. Einar also says it can be likened to Romulus and Remus, legendary founders of Rome, who suckled from a she-wolf. Consequently, it stands for an intercultural interchange of medical learning.

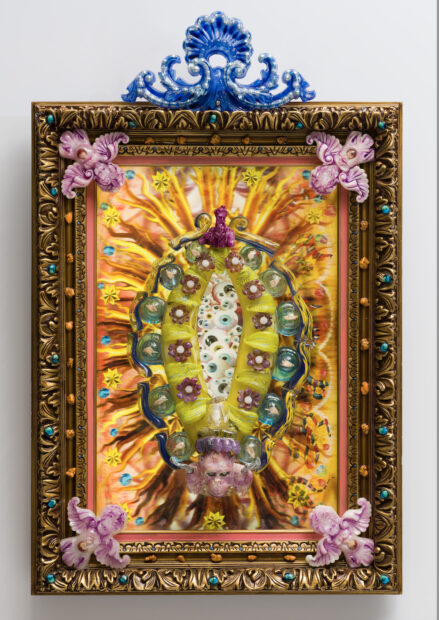

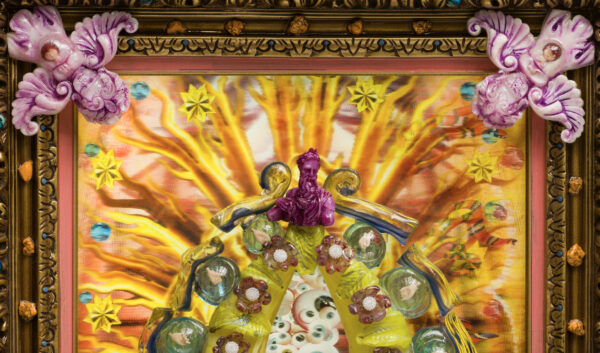

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Thoughts and Prayers,” 2020, blown glass on archival lenticular print in LED lightbox with resin castings 47 x 30 x 7 inches framed. Photo: Philip Ritterman.

Thoughts and Prayers includes blown-glass elements that are attached to a lenticular print. The latter are made by combining two or more images by cutting them into thin strips and reassembling alternating strips into a single image. Such images appear different when seen from different angles. The de la Torre brothers appreciate the “unparalleled depth” these images provide. See the Collidoscope review for a fuller discussion of lenticular prints.

The central image in Thoughts and Prayers is a depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe’s mandorla (hence the green color). As Einar describes this form, “it is part of a series of Virgenes – minus the virgen – a kind of ‘portal of life.’” This portal has a vaginal shape, like others in the series discussed in the Collidoscope review. It is crowned by a miniature version of Michelangelo’s Moses, who occupies the position of the clitoris. He’s doing oversight. A monkey at the bottom takes the place of the angel that normally supports the Virgin of Guadalupe. Notwithstanding these irreverent substitutions, this is a serious piece.

The background image is from a church ceiling in Prague. Depending on the angle from which one looks at the piece, snakes appear on the sides of the portal. Deadly coral snakes have red, yellow, and black bands, but so do kingsnakes, their harmless Batesian mimics. Einar refers to these snakes as “a floating metaphor.” Snake imagery is widely utilized by the Catholic church, but, as these colorful snakes demonstrate, it is not always easy to determine who is truly dangerous.

The eyes in the center of the portal are souls waiting to be born. From other angles, one sees a burning candle with recumbent nudes in the center (these derive from wallpaper the brothers made to symbolize sloth). The gesturing hands that surround the portal are taken from toy dolls. They reminded the artists of gang hand signs.

Thoughts and Prayers has no gun imagery, no bullet holes, no reference to the National Rifle Association (NRA), because it was not conceived as a work about gun control. Initially a work that concerned prayer, Thoughts and Prayers became a work about life. The title came later.

In an early stage of thinking about this piece, the brothers asked themselves: “What are we praying to when the Virgin is absent?” With its panoply of saints and intercessors, the brothers consider Catholicism to be as polytheistic as Hinduism.

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Thoughts and Prayers” (detail), 2020, blown glass on archival lenticular print in LED lightbox with resin castings 47 x 30 x 7 inches framed. Photo: Philip Ritterman.

In the four corners, bird-like, pink-purple glass cherubins whisk away the souls of children (represented by their heads in a transparent capsule) who have been killed by gunfire.

Einar points out that the title Thoughts and Prayers references “the gun lobby’s mantra of ‘thoughts and prayers.’” Endlessly repeated after fatal shootings in the U.S., it has been completely ineffective. Einar avers: “what we really need is strict gun control.” The brothers condemn the mendacity of the NRA, and all those who elevate gun rights above human rights – understanding the latter to include the right to continue living. Einar applauds the anti-Trump election meme: “Christians have warned about the anti-Christ for 2000 years. Now that he has appeared, they voted for him.”

There’s a lot going on in the de la Torre brothers’ glass pieces, and I wish the McNay had provided narrative labels to help viewers grasp some of the issues they are confronting in these works.

Le Point de Bascule (the Tipping Point)

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Le Point de Bascule provides an expansive context for a feast on the large table in the center of the room. The above view, from the entrance, shows light-colored wallpaper with arabesques on the left. These walls are peppered with stuffed animals, symbolizing human dominance of the natural world and the propensity of wealthy humans to hunt, kill, and utilize exotic animals as trophies. The wall on the left is mirrored by a wall on the opposite side with similar decorations.

The far wall in the above illustration is dark and ominous. Upon closer examination, the architectural elements depicted in it are photographically transformed into negative images. The entire wall is fictively composed of small tiles, with larger, blue-and-white plates set into it.

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The central table is set for a luxurious meal with extremely affluent guests, given the fur coats that are draped over several of the chairs. In his film The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), the great Surrealist director Luis Buñuel humorously portrays a group of corrupt, aristocratic would-be diners, who, in the course of interlocking dream sequences, are perpetually frustrated in their attempts to have a proper meal. In Le Point de Bascule, we have seemingly stumbled upon a case of banquet interruptus. The food is served, but all of the people are inexplicably gone.

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Upon closer inspection, the meal at hand is grisly beyond belief. The present course consists primarily of infants in red sauce. This cannibalistic blood feast also features enucleated human eyeballs, excised hearts, severed hands, and other body parts, all ready to be devoured by a discerning clientele. Partially-sipped wine shows that the diners did not bolt from the table because of the menu.

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail with “Capitalist Pig” and stuffed warthog in background), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The table’s centerpieces bespeak the class status of the diners. The most explicit is a top-hatted glass pig titled Capitalist Pig. It bears a dollar sign on each of its flanks, and it defecates gold coins, signaling that the dinner guests are themselves bourgeois pigs, who wallow in this class-based, monetary iconography. The stuffed animals and fur coats further signify a predatory attitude towards the natural world. A course of candied infants merely extends this predatory approach to the lower classes of humans, who are not just oppressed in the workplace, but literally consumed at the dinner table.

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail with “The Stinking Rich Fly”), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Le Point de Bascule’s primary centerpiece is a four-armed, top-hatted man with what looks like an elephant’s trunk and the bulging eyes and the wings of a fly. Called The Stinking Rich Fly, it is a fly-human hybrid inspired by the original science fiction film The Fly (dir. Kurt Neumann, 1958). (Einar does not care for the 1986 David Cronenberg remake). In the film, a scientist, experimenting with his molecular transporter, inadvertently scrambles his molecules with those of a housefly. The fly’s head replaces his own, and, as he terrifyingly experiences the continued loss of his human consciousness, he causes his own death.

The Stinking Rich Fly (which has nothing to do with Ganesha, the elephant-headed Hindu god) is clearly losing his humanity in favor of filthy lucre. He stands on piles of gold coins and he grasps two money bags. With his six limbs, fly wings, enormous eyes, and a trunk-like proboscis, he is more fly than man. Unlike the protagonist of the film, this creature welcomes his transformation into a giant, dirty, greedy fly. The de la Torre brothers did not intend for the proboscis to reference the Republican Party, whose emblem is an elephant, but their attitude is that if the proboscis fits, wear it.

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail of table with “handelier”), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The “girl-chandelier” was an astonishing invention featured in the Marilyn Monroe vehicle Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (dir. Howard Hawks, 1953). (It is visible in the trailer linked here.) In Le Point de Bascule, the de la Torre brothers have created what I call a “handelier” – a chandelier made of extended human arms and hands.

Attempting to follow the logic of this piece, I assumed that these limbs were intended to represent taxidermied human body parts. That would mean that these people — like the stuffed animals surrounding them — would have been killed to compel them to serve the rich as a perpetual spectacle. They were, I assumed, light-bearers for the rich, available twenty-four hours a day at the flip of a switch.

Einar informed me, however, that the arms and legs are synecdochal stand-ins for rebellious underlings. Instead of wielding convenient light, they are brandishing makeshift torches, crafted out of broken wine glasses. In this fashion, class rebellion obtrudes into the spectacle of the grand banquet, like the armed guerrillas from Miranda at the end of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. They too provide a narrative explanation for the absence of high-rolling diners, who could have fled without their valuable fur coats out of fear for their lives.

Beneath the table, the de la Torre brothers have created a photo-mural of raw hamburger, laid out in long decorative patterns, like bones lining certain crypts and ossuaries. This ground-up, decorative meat is also intended to give expression to the unwilling servitude of the working class. Almost out of sight — except to the most inquisitive viewers — this spectacle is not a pleasant one. Einar likens it to “how sausage is made,” a process its marketers want to keep private, and one its consumers “really don’t want to see.”

The brothers endeavor to make open-ended work that is subject to multiple interpretations, in the present as well as in the future. As Einar explains, “our artworks have to exist without us being around to defend it.” Nonetheless, it would have been advantageous to have more guiding texts for visitors to the exhibition at the McNay.

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail of taxidermied warthog), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. On the table, an agave plant grows through a human skull, beside a bloody child. The warthog, like the other animals, wears a golden medallion. A human heart is stuffed into a large wine glass on the other end of the table. In the wallpaper one can see anthropomorphized human hearts and arabesques that terminate in human brains.

The title Le Point de Bascule references the two-degrees Celsius increase in temperature that scientists regard as the “tipping point” for global warming. It is a threshold that — after it has been breached — there may be no way to return to earlier lifestyles and standards of living. Extreme weather, melting ice, and rising seas will result in droughts, floods, mudslides, famines, desperate migrations, and deadly conflicts over food and potable water that could imperil many of the inhabitants of this earth.

By not including the diners of this sumptuous feast, the de la Torre brothers saved themselves the trouble of creating them. But let us apply the logic of the Anthropocene (the current epoch in which human activity has had a significant impact on climate and ecosystems) to this scenario. The diners have vanished. They represent the ever-rapacious, overconsuming elite. Their disappearance, therefore, can symbolize the ever-more probable extinction of the human race due to overconsumption and ecological disregard. The infant feast spread on the great table, it follows, could stand for the affluent devouring future potential generations, including their own progeny.

Einar calls overconsumption “a form of cannibalism.” He points out that we are trodding the path blazed by other animals that achieved dominion. They also overproduced and damaged or destroyed their ecological niche. The difference is that humans have vastly greater powers. That is why gluttony for the good life could end all life as we know it.

Le Point de Bascule, then, is a kind of warning, wherein the symbolic disappearance of the diners can be read as a harbinger of extinction. Such an impressive spectacle comes at a great cost, both individual and planetary. Only the super-rich would be invited to a dinner such as this one. The filthy rich, with their private jets, yachts, heated swimming pools at multiple mansions, rocket trips into outer space, etc., are the greatest culprits. Yet, less well-heeled contemporary witnesses to such overconsumption may often be ambivalent. “The palimpsest of the revelers,” says Einar, “leads us to despise and envy them.”

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail of faux-tile wallpaper with furniture from the McNay colonial revival mansion), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. A skeletal figure bearing gold coins emerges from an updated Tlaloc vase, while a one-eyed anthropomorphized human heart raises its fists.

The de la Torre brothers are not letting the other inhabitants of affluent nations off the hook. “This is the quandary of our contemporary existence — we know we need to change our lifestyle, but who really does?” queries Einar. This is why the de la Torre brothers fear that the two-degrees threshold will be exceeded. “We are too entrenched in our ways,” warns Einar, “and we will all be guilty if we miss this deadline.”

“Le Point de Bascule” (the Tipping Point) (detail of skeleton and vase), 2024, mixed media installation at the McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The first version of this installation was made at Kunstfort in Asperen, Netherlands in 2017. Others were staged at the Lille3000 festival in France (where the “El Dorado” theme led to the use of gold), the SIC! City Gallery in Wroclaw, Poland, the Museu do Vidro in Marinha Grande, Portugal, and it is now at the MusVerre at Sars Poteries, France. It was revamped (including the addition of taxidermies) at the Institute of Contemporary Art in San Diego last year. The iteration at the McNay is larger and more complex than these other versions, and it includes a considerable amount of new material.

Two Horror-Filled Large-Scale Lenticular Prints

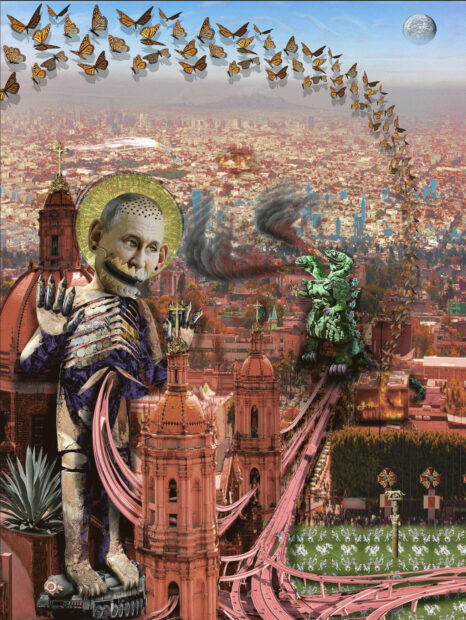

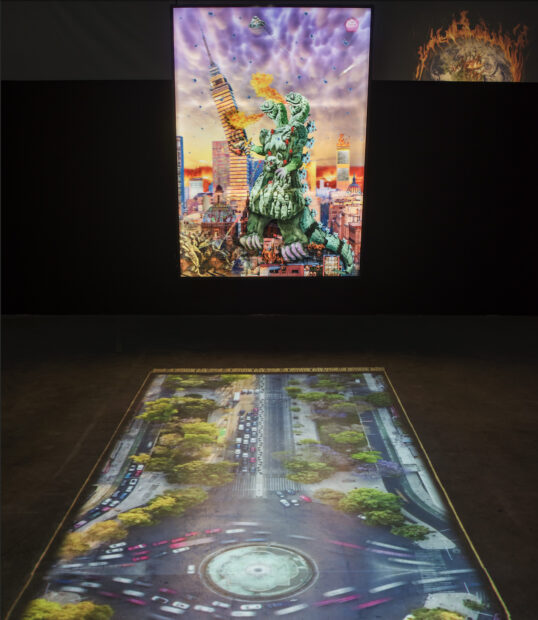

“Coatzilla,” 2023, lenticular print and LED light (suspended lenticular with video floor projection), 96 x 60 inches. Installtion view in “de la Torre Brothers: Post-Columbian Futurism,” 2023, Institute of Contemporary Art, San Diego. Photo: Philip Ritterman.

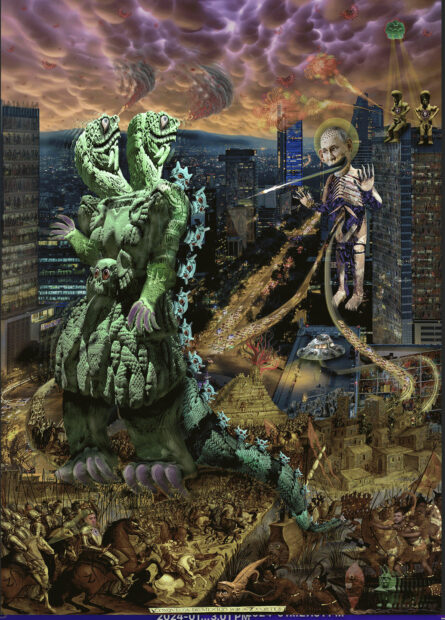

The de la Torre brothers describe the two large lenticular prints in this section as virtual “monster movie posters.” Both monsters are out to destroy human civilization, though their destructive acts are antithetical because they stem from antithetical motivations.

The two lenticular prints face one another, while a feed of the traffic interchange at the Paseo del Reforma in Mexico City is projected onto the ground between the two prints. (See this video for the work in action.) This projection has the effect of situating the visitor to the exhibition in Mexico City. Importantly, it also creates the sense that the visitor, too, is a giant monster who obliviously tramples cars underfoot, and who is likewise a powerful and destructive force to be reckoned with.

“Source image for Coatzilla” (the monster is destroying a building while a tank fires on it), 2023, one of the approximately 50 images that were synthesized into the Coatzilla lenticular. A source image such as this one is never seen completely at one time while viewing the finished work. Instead, various images combine as the visitor moves in front of the work.

The monster Coatzilla combines the Aztec life-death goddess Coatlicue (illustrated and discussed in the Collidoscope review) and Godzilla, the popular Japanese science fiction monster that first appeared in Godzilla in 1954 (dir. Ishirō Honda).

“Coatlicue,” Aztec, c. 1487-1520, from Tenochtitlán, stone, 8 feet, 3 inches high, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

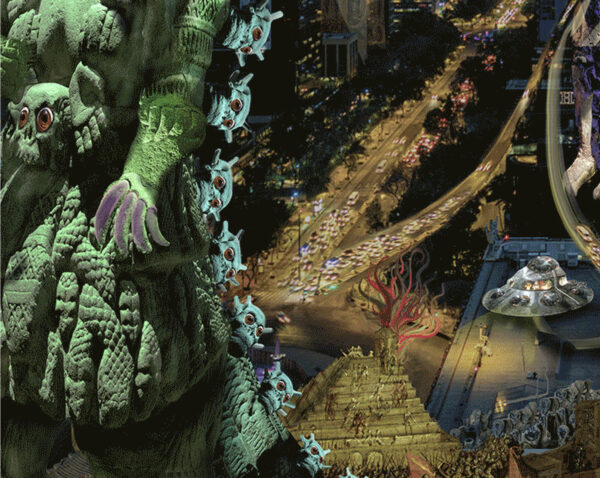

Most of Coatzilla’s features come from Coatlicue. The de la Torre brothers’ creature has twin serpent heads. In the Aztec sculpture pictured above, they are understood as jets of blood combining to form a single living face to replace Coatlicue’s severed head. The de la Torres separate the two jets of blood, while maintaining their anthropomorphized character. Coatzilla also has the topless female body, the woven rattlesnake skirt, the garland of hearts and hands, and the central skull ornament possessed by Coatlicue. In Coatzilla, Coatlicue’s severed arms are restored, and her eagle taloned feet are set in motion.

The de la Torre brothers’ composite creature has large dinosaurian scales on its back, similar to those possessed by Godzilla, but they take the form of skulls, closely based on those on the front and back of Coatlicue. The dinosaurian tail is also based on Godzilla, but the rattlesnake and feather patterns on it derive from Coatlicue. Coatzilla’s flaming “atomic breath” is a power derived from Godzilla, who was awakened from an eons-long slumber by nuclear bomb testing. Rather than perishing from the radiation, Godzilla absorbed and internalized this destructive atomic power, and unleashed it on Tokyo and other Japanese targets.

Coatzilla is set in Mexico City. The creature’s flaming breath has toppled the Torre Latino Americano, the city’s preeminent skyscraper (loosely based on the Empire State Building). Behind it, one can see the mosaic-covered library building of the national university, and on the right, the golden dome of the Palacio de Bellas Artes. The world outside of the city is aflame, with the implication that Coatzilla was awakened by environmental degradation caused by global warming. The creature wants to put the final touches on the extinction of the human race, which resists with a tank, rockets and even a spaceship.

“Source image for Coatzilla” (Mictlanteputin attacks Coatzilla), 2023, one of the approximately 50 images that were synthesized into the “Coatzilla” lenticular.

The above image features a King Kong versus Godzilla scenario in which Mictlanteputin attacks Coatzilla from behind with a missile that blasts out of his hinged mouth. Coatzilla turns her heads around, but her scaly back is still facing her nemesis.

“Source image for Coatzilla” (detail of previous image), 2023, one of the approximately 50 images that were synthesized into the “Coatzilla” lenticular.

In the above image, one can see how Coatzilla’s scales are fashioned out of Coatlicue’s ornamental skulls. Also note the burning pyramid (a symbol of conquest utilized in Mesoamerican codices (books) and the flying saucer above it, which adds a quixotic sci-fi element into this already heady mix.

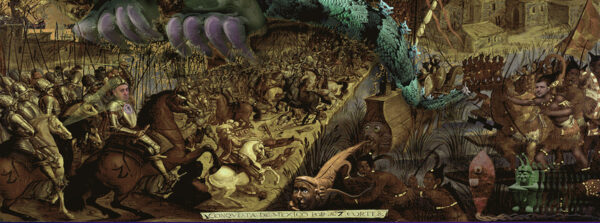

“Source image for Coatzilla” (detail of bottom of the last full image illustrated above), 2023, one of the approximately 50 images that were synthesized into the “Coatzilla” lenticular.

In the detail illustrated above, armies from different lands and different timeframes are doing battle. An army of knights on the left ride horses with a “Z” brand — a reference to the markings borne by Russian armored vehicles in the ongoing Ukrainian War. Yevgeny Prigozhin, the now deceased former leader of the mercenary Wagner group looks towards the viewer in the lower left. On the right, the Aztec resistance is led by none other than Volodymyr Zelensky, the president of Ukraine. The inscription in the center references the Conquest of Mexico by Cortez. Thus the Russian invasion of Ukraine is likened to a colonial conquest. In between them, a man on horseback resembles a Diego Velazquez portrait of Count-Duke Olivares.

In the lower right, we see an Aztec drum, an anthropomorphic sacrificial knife (such as those excavated at the Templo Mayor), and a stone sculpture of Xiuhtecuhtli, the old god of fire. These elements form part of the backdrop for a battle royal between composite monsters. On upper levels shacks and pyramids give way to skyscrapers and highways. In another update, Coatzilla spews Covid-19 into the atmosphere (see full shot illustrated above).

The monster Miclanteputin is a mash-up of Mictlantecuhtli (the Aztec god of death and the underworld) and Vladimir Putin, the Russian President.

Mictlantecuhtli (with author in the background), c. 1480, fired clay, stucco and paint, height 176 cm., Templo Mayor Museum, Mexico City.

The large-scale ceramic statue pictured above is one of two that were excavated in the Templo Mayor’s House of Eagles in 1994. This is the statue of Mictlantecuhtli that the de la Torre brothers merged with Putin’s face, which is superimposed over the god’s head like a mask. The holes in Mictlantecuhtli’s head served to fix his wig. Here they humorously transition to Putin’s closely-cropped hair.

Putin’s cold, shark-like eyes seem to be behind the mask he wears, rather than an organic or integral part of it. Soviet general’s medals are integrated into his rib cage, symbolizing Putin’s warmongering belligerence. Astonishingly, Mictlanteputin is adorned with a halo as he floats in the air. Or so it seems: his halo is actually a gold-colored wire wheel, another reference to lowrider culture.

Mictlanteputin’s body is wholly that of Mictlantecuhtli, with outstretched and menacing clawed hands (his fingers sometimes appear as missiles). He fires a missile at Coatzilla from his open, hinged jaw.

Mictlanteputin retains the flower-like form emanating from Mictlantecuhtli’s ribcage. It is the god’s liver, understood as a seat of the ihíyotl (spirit). In Mesoamerica, the liver was traditionally associated with death and Mictlán (the underworld). Mictlanteputin continues this tradition by spewing highways — soon filled with cars — from his liver. This monster is a threat to the human race because, in devil-like fashion, he gives the people what they want. Bring on Carmageddon!

In the above image, Mictlanteputin is integrated into the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe. A kaleidoscope of butterflies (which represent the souls of Aztec warriors who died in combat or by sacrifice) takes flight. Coatzilla, seen in the distance, is headed in Mictlanteputin’s direction.

Both simulated movie posters deal with struggles over the earth and its resources. But, as Einar notes, while the creature Coatzilla is destroying humanity out of anger at our “mismanagement of the natural world,” Mictlanteputin, on the other hand, “revels in, and is all for the continuation of the industrial revolution in all its juggernaut glory of consumption.” For Mictlanteputin, it’s more highways, more cars, more refineries, more hell-on-earth heat and carbon monoxide. Pick your poison, because both monsters want us dead.

Colonial Atmosphere

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere,” 2002, mixed media sculpture installation, 140 x 360 x 450 inches, McNay Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In my Collidoscope review, I referred to Colonial Atmosphere as the de la Torre brothers’ “most astounding installation” to date — though I think most viewers would agree that Le Point de Bascule, in its enlarged iteration at the McNay, at the very least gives it a run for the money.

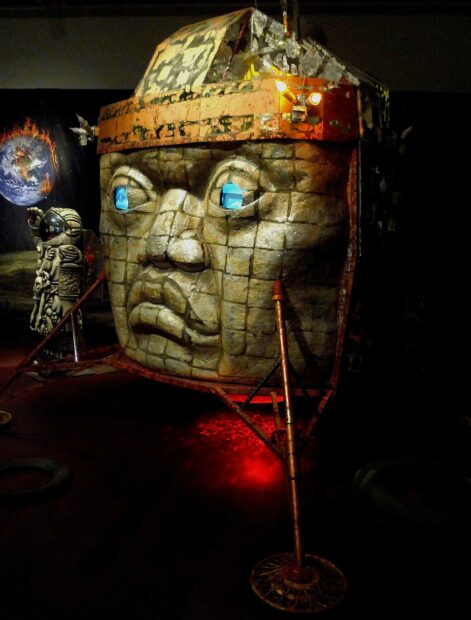

The conceit behind Colonial Atmosphere is that the great Mesoamerican civilizations (represented by the Olmecs and the Aztecs) have colonized not just other Mesoamerican societies, but the moon as well, with all that implies in terms of technological proficiency and dominion over the other countries on the earth. This Post-Columbian Futurist outer-space safari is dominated by a lunar lander in the shape of a monumental Olmec head from La Venta (replete with wire rim landing pads).

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail), 2002, mixed media sculpture installation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

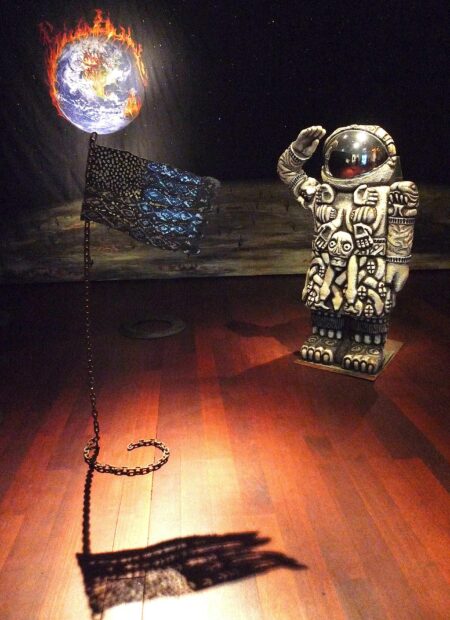

It also features an Aztec-cosmonaut in the form of the goddess Coatlicue (who wears a heart-powered jet pack on her back). (See my Collidoscope review for more photographs and a comprehensive discussion of this installation.)

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of Coatlicue and her jet pack), 2002, mixed media sculpture installation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Due to global warming, the Earth, as seen in the painted backdrop, is a ball of fire. Space, heralded as the New Frontier during the original “space race” in the 1960s, will be the new home of earthlings, whose planet is destroyed not by invaders, but by the excessive utilization of terrestrial technology.

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail), 2002, mixed media sculpture installation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Coatlicue is the new Neil Armstrong, and she renders her flag (made up of transistors and rattlesnake patterns) an equally crisp lunar salute. In this darkened chamber, the rhinestones attached to the painted backdrop glitter like distant stars.

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail), 2002, mixed media sculpture installation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

To complete the transhistorical mestizaje (racial and cultural mixing) of the Mexican homeland, the lunar lander is piloted by a European-looking Christ child astride a stuffed horse. This renders him a Horseman of the Apocalypse, and also collapses him into the myth of the god Quetzalcoatl, and his prophesied “return.” Additionally, the Christ child’s pose replicates the position of King Pacal of Palenque on his sarcophagus lid (which is reproduced on the rear of the module). This in turn references the fraudster Erich von Däniken, whose pseudo-archaeological Chariots of the Gods? (first published in English in 1971) posited that “gods”-from-outer-space constructed ancient archaeological monuments.

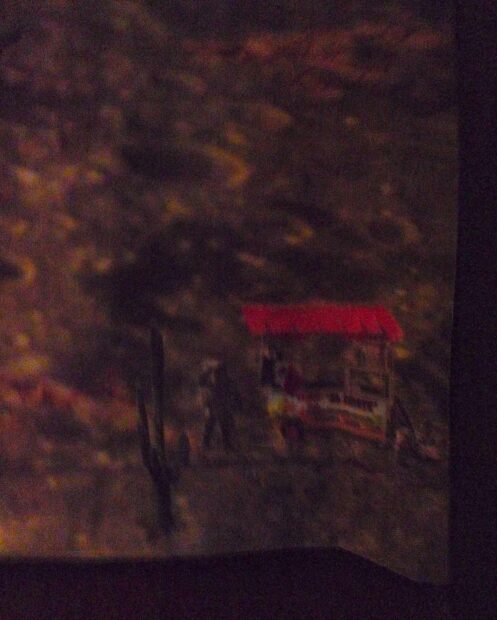

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of Taco Stand), 2002, mixed media sculpture installation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the darkest lower right corner of the painted backdrop, one can just make out a blurry taco stand, already manned by an intrepid vendor. Mexico’s destiny is thereby rendered clear: in multiple acts of Vendor Colonialism, Mexicans will conquer outer space, one taco stand at a time.

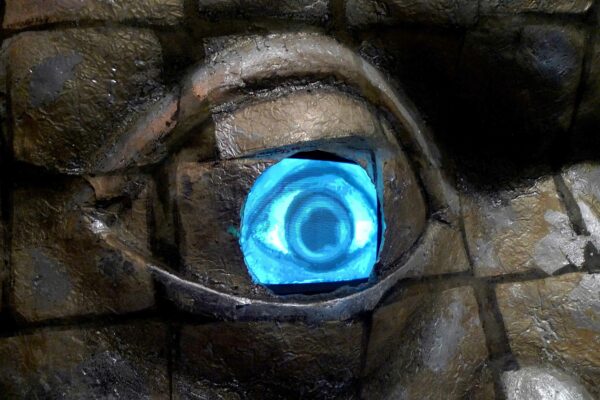

Einar & Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of eye), 2002, mixed media sculpture installation. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

With all the mythic content that the de la Torre brothers have piled into Colonial Atmosphere, perhaps the wise old Olmec head should give an occasional wink to the visitor.

Upward Mobility is a tour-de-force exhibition, or, better yet, four tour-de-forces in one. This important and beautifully installed exhibition is at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio through September 15, 2024, and it should not be missed.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than 30 exhibitions. His next exhibition, Dining with Rolando Briseño: A Fifty Year Retrospective, opens August 13 at Centro de Artes in San Antonio.