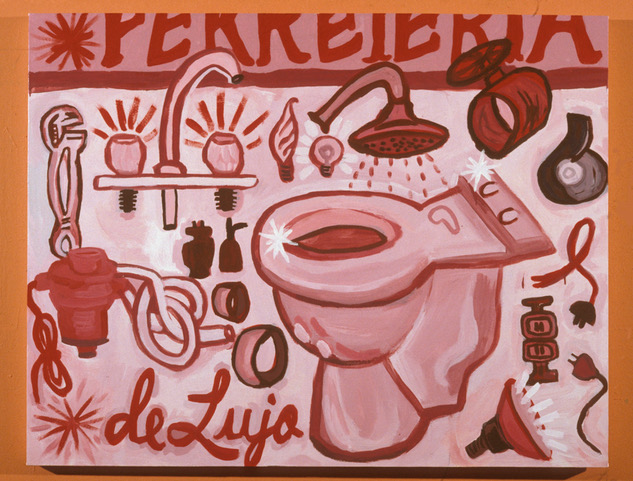

Victoria Suescum, Ferreteria Palaya Gorgona, 1996. Re-imagines the collage wall. Housepaint on canvas, exhibited at Mujeres en Las Artes conference in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Photo by the artist

Leave it to an artist to push for redefining the popular conception of folk art. San Antonio artist Victoria Suescum is doing so in her current show at in San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum called Tienditas: Victoria Suescum’s Folk Pop.

In order to promote Suescum’s show, as well as the San Antonio Museum of Art’s rechristening of its Latin American Folk Art collection as the Latin American Popular Art Gallery, curators Lucía Abromovich from SAMA and Lyle Williams from the McNay spoke in a virtual panel with Suescum called “Demystifying Folk, Fine, and Popular Art” in November, moderated by SAMA’s Public Programs Manager, Yohanna Tesfai.

Demysitification took the form of clarification: all the panelists acknowledged that folk art has been largely ignored by academicians, but that, as Suescum says, the images from which she draws her inspiration are part of a visual tradition of commercial street art and signage. “What needs to happen,” says Suescum, “is that the respect we feel towards folk artists needs to rise to the same level as Western fine art.” That European art is seen by many as classic and is therefore prioritized by art historians only serves to reinforce elitism. Conditioning begins early in art education; even young children are familiar with Michelangelo and his works, for example, but because folk artists are often characterized as anonymous, almost interchangeable, there is no romantic cult of genius that develops around them.

Tesfai’s observation that classic European works were intended to appeal to audiences every bit as much as folk art (henceforth “arte popular”) created a segue for Suescum to argue that city streets in Panama, Honduras, Mexico, as well as here in San Antonio are sites of art, too. Suescum calls hand-painted commercial signage along streetscapes “corridors of art,” and she maintains that she studies them with the academic rigor that others reserve for European art.

Detail of Victoria Suescum’s Mini-Super. The tactile quality of the paper and installation-via-thumbtacks boost the playfulness running throughout the pieces. Photo: Christina Frasier

From the slideshow of her featured work in the talk, I certainly saw the iconography of hand-painted signage: the corn on the cob, the raspas, the tires. But it wasn’t until I went to the McNay and saw her work in person that I really saw that Suescum was serious. Her works installed in the McNay are frameless, with the paper buckling like old paint delaminating from a wall in the hot South Texas sun. Her reinterpretation of signage is looser and more playful than the originals, some of which I have photographed for my documentary work, and some of which Suescum showed me in an interview from her travels in what she calls the “Spanish-speaking portions of the Americas.”

Photo of a ferreteria, or hardware store, along the Panamerican Highway in Playa Gorgona, Panama. Photo: Victoria Suescum

In the interview, I asked Suescum to elaborate on what she’d said in the talk about studying signage with academic rigor — I have heard some elevated rhetoric from artists over the years regarding visual analysis of their subjects. But Suescum’s claim is not hollow: she shows me a photo she took of a hardware store on which paintings of woodworking tools and plumbing items are rendered individually and out of scale. One of the larger items is a pink toilet, which is rendered with less detail than the other items. “The pink toilet is a fancy item, and whoever painted it did not give it that coil so that it will flush properly. There’s no seat. They don’t know how the toilet works. And so I find it fascinating that the items that they might use themselves are clearly explained — auto parts are clearly understood — but then fancy items are not. Toilets are not a given there.” The shower head is also rendered with less detail (fancy), whereas the wrenches and levelers (not fancy) are comparatively intricate.

The wall, I notice, does not show the painter’s signature. However, here in the U.S., hand-painted signs increasingly have contact information for artists. The more sign painters who identify themselves on their work, the less people can ignore them as anonymous, and the more often researchers can find them and talk to them and bring them into the fold.

Featuring overlooked artists is clearly the intent of SAMA’s Latin American Popular Art Gallery. In the panel, Abromovich says she had Suescum’s work in mind as she was developing the popular art gallery; Suescum’s work creates a positive feedback loop of art in San Antonio where hierarchies established by the academy are questioned. To compartmentalize art as fine or not works to effectively “other” vast quantities of visually appealing works that are part of a tradition, a cultural through-line across the Americas. Looking through a lens that does not privilege European art reveals rich and exciting work by painters, no matter how they characterize their work — fine or commercial.

Works by Victoria Suescum. Hand-painted signs for tienditas often feature paintings of the goods or services they offer. Acrylic on paper. Photo: Christina Frasier

Another positive feedback loop I noticed was the partnering of SAMA and the McNay. I was excited to read about Abramovich’s approach to arte popular and equally impressed that Williams is championing an artist who uses arte popular as a visual reference; their united front in claiming that arte popular is straight-up art with no qualifiers is an example of how museums can curate collections rooted in the traditions and interests of their visitors.

And, if you are are itching to see some art on days when SAMA and the McNay are closed, please stroll or roll down South Flores, Nogalitos, or Zarzamora Streets here in San Antonio. There is art all over the city, if you are are looking through a clear lens.

Through Jan. 10 at the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

Ed note: The author is the recipient of Glasstire’s 2020 San Antonio Art Writing Prize.