Installation view of “Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains” at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts

In conjunction with the 2024 Texas Ceramics Symposium, Texas Tech University’s School of Visual Art’s Landmark Arts is hosting Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains, currently on view at Lubbock’s Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts. The exhibition, curated by Klinton Burgio-Ericson, a Texas Tech University Assistant Professor of Art History of the Americas, features the contemporary ceramic works of seven Native American artists. These artworks range from vessels to sculpture to installation, and include pieces by Karita Coffey (Comanche), Chase Kahwinhut Earles (Caddo), Anita Fields (Osage, Muscogee), Raven Halfmoon (Caddo, Choctaw, Delaware, Otoe), Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota), Jane Osti (Cherokee National Treasure), and Cortney Yellowhorse-Metzger (Osage).

Installation view of “Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains” at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts

The exhibition’s theme of belonging does not confine itself to identity, an often politicized concept that implies choice-making. Belonging, rather, is inherently relational and is tied to place, time, culture, and kinship. Belonging is an affirmative, Burgio-Ericson explains, a rich term signifying “mutual obligation and reciprocity.” Throughout the exhibit, there are markers of connectedness: to family, homeplace, geography, and community; even the medium of ceramic itself, encompassing the elements of water, land, and fire, holds properties of location/topography, of site-specificity. As Anita Fields described during the exhibition’s symposium keynote conversation on February 23, because clay is of the land, it has a memory, and “because clay has a memory, it allows me to give expression to my own memories.”

The role of interconnected place-community-memory in belonging is evident in Karita Coffey’s sculpture My First Memory, which conveys what she described as a “flashbulb” memory, or a first arrival of consciousness, at the age of eight months. The work depicts a prone baby whose body is in the form of a house — the home of Coffey’s grandfather — which is filled with people, convened for a prayer meeting of the Deyo Indian Baptist Mission. In her recollection, Coffey is swaddled in a blanket upon her mother’s lap. The piece interweaves her own dawning awareness of belonging, while also speaking to layers of themes from acculturation to community connectedness to land allotment policies and identification with place. Coffey asserts a recognition of her grandfather’s land as alive, thinking, and possessive of “blood memory,” explaining in the keynote conversation, “Because we inhabited that land, it’s Comanche.”

Installation view of “Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains” at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts

Other artists also invoke relational belonging through familial/cultural memory, as with Jane Osti’s Circles of Belonging, Chase Kahwinhut Earles’ Large Caddo Traditional Utilitarian Jar, and Anita Fields’ It’s a Bucket With a Lid On It. In these pieces, as well as others that adopt the familiar ceramic form of jars and vessels, there is an homage not just to tradition in general, but to specific family practices and lore. For example, through humor and biting satire, It’s a Bucket refers to an oft-shared story in Fields’ family, in which her grandmother — while considering the purchase of a large enamel pot in a store in Florida — turned to another family member and asked in Osage, “Hanontze,” or “How much is it?,” only to have the salesman move in closely to offer at a yell, “It’s a bucket with a lid on it!” Understanding that he thought she couldn’t recognize a bucket, Fields’ grandmother responded seamlessly in English, “I know it’s a bucket with a lid on it.” The artist points out that, by claiming this story as a humorous episode, shared again and again, the family “transformed a racist and dehumanizing moment into familial bonding, draining it of its venom.”

Installation view of “Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains” at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts

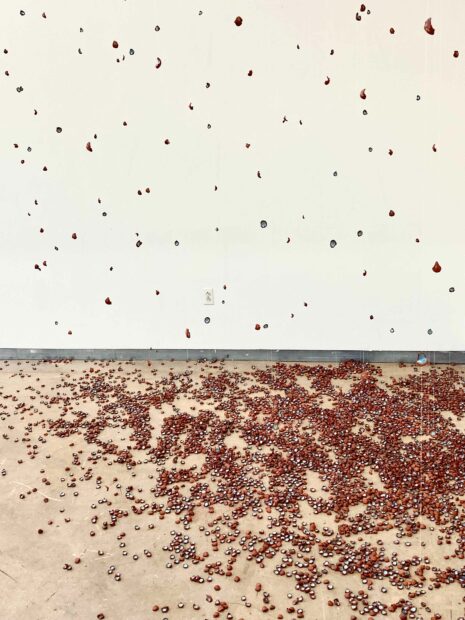

Cortney Yellowhorse-Metzger, in using her own fingerprints, likewise explores her connectedness to (intergenerational) family and friends, and their care for one another, through such installations as Tears of the Sky People and Tho-day-they (To Live in Friendship). The former consists of a meditative assemblage of tiny bowl-like fingerprints, the whorls of which are alternately obscured or defined by sky-blue glaze. Some of these delicate vessels are suspended in midair while others lay pooled on the floor, with each “tear”/bowl representing a part of a larger whole. The latter work, Tho-day-they, includes fingertip impressions that, petal-like, fill the interior of a shallow bowl form; slip-painted handprints fan outward from this nucleus, as symbols of caretaking, joy, and loving engagement with elders and community.

Perhaps inevitably, the theme of belonging also explores inclusion and exclusion, openness and aggression, resident and alien. Examples of these ideas occur in Cannupa Hanska Luger’s Rounds, Raven Halfmoon’s Cowgirl at Heart, and Anita Field’s Do Your Best. In such works as Sky People and The Scout, Chase Kahwinhut Earles adopts extraterrestrial motifs, such as UFOs and the Star Wars-inspired Imperial scout droid, to investigate issues of cultural belonging, colonialism, betrayal, and (loss of) autonomy. Referring to his work as Indigenous Futurisms, Earles points to science fiction’s “narratives of encounter and colonization; by reworking such images, [he] asserts agency over these present-day mythologies, and posits an alternative temporality.”

Part of a Texas Tech University initiative to expand its curriculum toward strengthening mutual relationships with the Native communities of the Southern Plains, the School of Visual Arts sees this Belonging exhibition as a launchpad for conversations to come. In this way, Belonging itself, with its extensive interpretive material and ties to the recent Texas Ceramics Symposium, acts as a dialogue, a reminder that we live in mutuality with one another. In the exhibition catalog’s essay, “Belonging: Then, Now and Always,” author Chelsea Herr (Choctaw) — Curator of Indigenous Art and Culture at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma — points out, “to live ethically in relation to one another, we must acknowledge that our existence affects and is affected by more than just ourselves. We must not only belong, but also extend belonging to others.”

Belonging: Contemporary Native Ceramics from the Southern Plains is on view at the Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts in Lubbock through March 23, 2024.