Delita Martin in front of “Follow the Waters,” 2024, installation. Image courtesy of the Galerie Myrtis and McClain Gallery. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

Delita Martin’s artwork on view at the University of Texas at San Antonio’s Russell Hill Rogers Galleries showcases everyday Black women subjects whose stories often go overlooked. Martin’s exhibition, Delita Martin: Her Temple of Everyday Familiars, A Retrospective, is indeed retrospective. Included artworks range in date from Martin’s very first drawing, which she created at the age of five on the backside of her father’s painting of Jesus, to more recent pieces from her 2023 series of twelve relief prints, Follow the Waters.

Delita Martin, “Under the Persimmon Tree,” 2023, relief printing, charcoal, acrylic, liquid gold leaf, hand stitching. Image courtesy of the artist and McClain Gallery. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

The Russell Hill Rogers Galleries comprise two rooms joined by an open space. The east room of the galleries showcases Martin’s installation, Follow the Waters, which surrounds the entirety of the room’s walls. The color blue overwhelms the compositions in each portrait of Black women in relief prints, which contain different combinations of materials such as acrylic paint, charcoal, lithography, liquid gold leaf, printed papers, and hand-stitching. Martin decorates the subjects’ clothing and background patterns with motifs that range from shapes, such as circles and hexagons, to stems of plants and sunflowers.

As a color, blue is spiritual and multifaceted in its symbolism. After all, blue is the color of water, but also, protection. The ocean heals, hence, why Martin’s words adorn the center of the composition:

I rush to the Ocean’s edge..

Somebody told me

The ocean could wash my blues away,

Carry them out to sea.

After all ain’t that how the water got its color?

Therefore, Martin’s portraits of Black women — who are surrounded mostly by blue, but also hints of yellows, reds, and purples — convey them to be spiritual guides over bodies of water. The women stare in different directions: some confront the viewer, while others look off to the side. Who are they, exactly? What is their story? These questions, I do not have answers for, but that is not the purpose of their imagery. Instead, the women are content, free as water, and they immerse viewers in a spiritual and physical realm.

Delita Martin, “We played among the tall Flowers, It was there that I first wanted to love you,” 2023, relief printing, charcoal, acrylic, liquid gold leaf, hand stitching. Image courtesy of the artist and McClain Gallery. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

Harmonies of material, pattern, color, and stance in these relief prints give life to what Martin dubs Afro-Cubism. The artistic style is characterized by the amalgamation of diverse, creative elements into a complete, melodious whole. Specifically, there are references to bold shapes and patterns that recall motifs of African art, such as, but not limited to, West African masks. Martin’s use of bold shapes and patterns emulates an experience that is spiritual, cultural, and shared throughout the African diaspora.

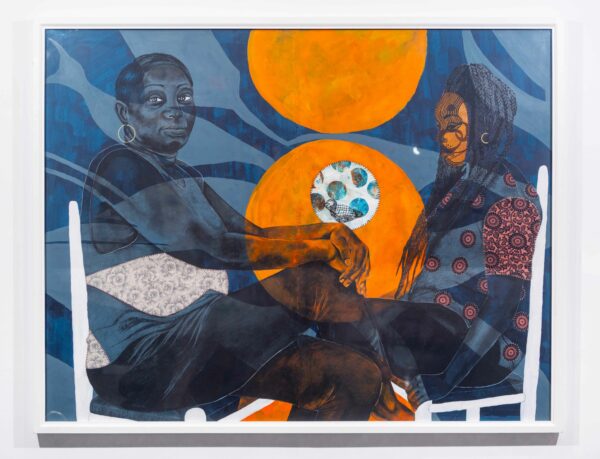

Delita Martin, “Moon and the Little Bird,” 2018, acrylic, charcoal, gelatin printing, collagraph printing, relief printing, decorative papers, hand stitching, liquid gold leaf. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

Moving to the west room, Martin confronts viewers with other artworks that demonstrate her use of Afro-Cubism to convey spiritual images of Black women. While each artwork holds its own significance, Moon and the Little Bird was an immediate standout to me. Martin considers this artwork one of her “veilscapes” — a transition space that visualizes the normally invisible spirit of people and objects. Fragments of flowers, shapes, and colors are once again combine in this artwork. A bird perches on the hand of an older woman on the left. The bird symbolizes the human spirit, and the animal, enclosed in circles of blues and sunset orange, looks eagerly at the woman. The unidentified, masked woman on the right gazes at the moon and the bird in the palm of the older woman’s hand. This artwork, portraying both a young woman and an older woman, shows us the theme of womanhood.

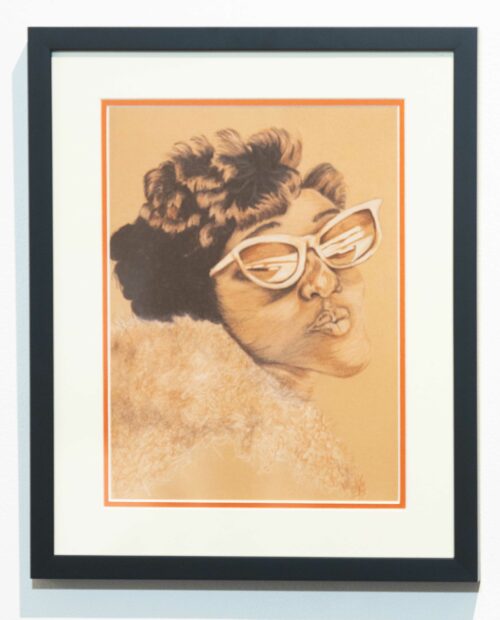

Delita Martin, “Untitled (First Self Portrait),” 1991, colored pencil. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

In the west room, Martin confronts viewers with some of her early artworks. For example, there is her 1991 colored pencil drawing, Untitled (First Self Portrait). As a high school student, Martin drew herself as a groovy teenager with sunglasses and pursed lips. Despite her confident glare, Martin tended to avoid self-portraits in her prints in the years to come.

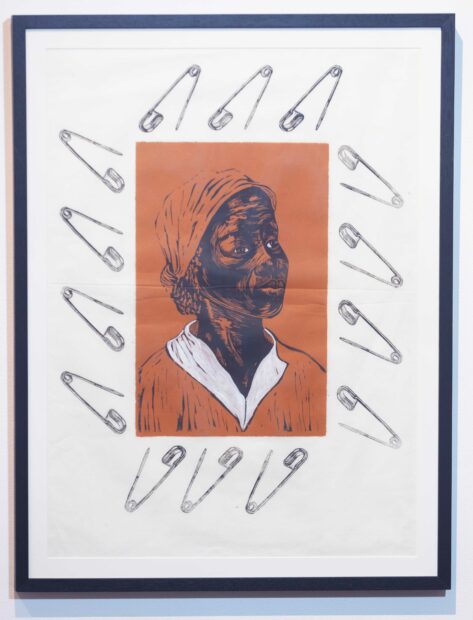

Delita Martin, “Effie (EH fee): She Speaks the Truth,” 2008, relief, hand-painting. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

Another early work, Effie (Eh fee): She Speaks the Truth, is a printed portrait of a Black woman that Martin has hand-painted. Her name, Effie, is inspired by the letters of enslaved women Martin found during her research as a graduate student at Purdue University, which is where and when she began creating prints. Safety pins, an example of a household item traditionally associated with “women’s work,” such as sewing, surround Effie. Viewers witness that early on in her artistic career, Martin’s interests gravitated to the narratives of Black womanhood.

Delita Martin, “The Dinner Table,” 2018, table, 6 chairs, 300 plates drawn in lithographic crayon, dimensions variable. Photo: Patrick Buckner Photography.

I was captivated by Martin’s installation, The Dinner Table, from 2018. The piece, which is site-specific, features 300 found and donated plates placed on one of the west room’s walls. Each plate displays the face of a Black woman or girl whom the artist first photographed, then drew with lithographic crayon. In front of the plates stands a table, where viewers can engage in conversation.

Almost immediately, I gathered that The Dinner Table borrows ideas from Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, which was a 1974-1979 artwork that toured the country and is now on permanent view at the Brooklyn Museum. Relatively few women represented in Chicago’s artwork are women of color, and Martin does not shy away from asserting her discontent with the contemporary art historical canon’s failure to include Black women subjects. Consequently, The Dinner Table is an homage to the everyday women of the African American community of Conroe, Texas, and creates a space that invites dialogue about these women and their contributions not just to their communities, but to the United States at large.

Delita Martin captures the spirit of Black women through expressive portraits that bond fragments of colors and symbols. This exhibit, featuring installations and prints with an array of mixed media garnered together, maintains a framework that gives viewers not only a glimpse of the spiritual essence of the Black women of Conroe, but also to the broader context of the African diaspora.

Delita Martin: Her Temple of Everyday Familiars, A Retrospective is on view at the Russell Hill Rogers Galleries at the University of Texas at San Antonio Southwest Campus through March 22, 2024.

1 comment

A small correction, Martin’s first drawing is on the back of her father’s painting of Jesus.