In November 2022, I made my first visit to the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) to get a tour of the main campus arts building. I enrolled in UTSA’s Master of Art History program earlier that fall, and wanted to become familiar with the space where I would be a student for the next two years. All of my potential professors were in a staff meeting, so Anahita Younesi, a graduate student in the Master of Fine Arts program at the time, gave me a guided tour of what would become a familiar terrain for me as a student, and eventually, as a lecturer.

While touring the campus, I questioned Younesi about her own artwork, and she explained that her practice was in a state of evolution: UTSA’s faculty prompted her to experiment with materials. Once mostly an oil painter, Younesi began introducing watercolors, textiles, and performance into her work.

Over time, we would share multiple classes. Younesi and I also formed a bond over the familiar feeling of leaving our home for an education, though Persia (Iran) is much farther from San Antonio than Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. Younesi’s references to Persian culture in her work were evident from the moment we toured the graduate studios. One day, near the end of the fall 2022 semester, she came to class with her head almost entirely shaved. I thought back to our conversation about her home and the protests that erupted around the time we met. She stated how hair is used as a symbol for women’s rights because, in her culture, hair is sacred, and often perceived as a symbol of life and birth.

Hair continued to be a central material in Younesi’s work moving forward. In the following interview, I delve into the symbolism of hair cutting for this self-proclaimed Persian artist.

Christopher Karr (CK): Why did you decide to become an artist?

Anahita Younesi (AY): I was interested in craft from childhood, and did things like sewing, knitting, and making collages from a young age. I started painting when I was five years old and continued to paint in college, and still have a painting practice. I really like crafting, and I focus on feminist art forms, like textiles, in order to discover myself as a woman.

CK: What interested you from the earliest time in your artistic career?

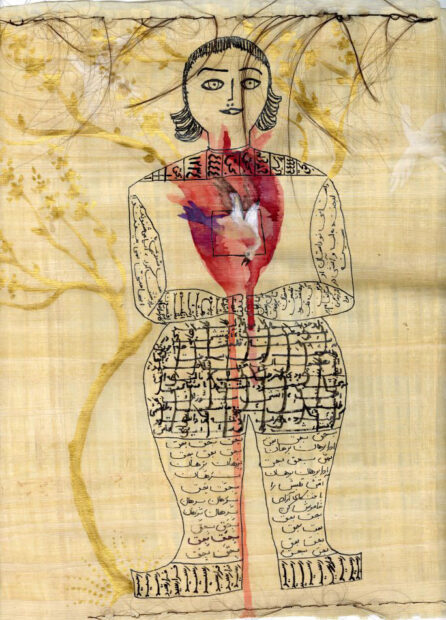

AY: I have always made art about the human body, but the way I use this concept has changed to more installation and performance styles of work.

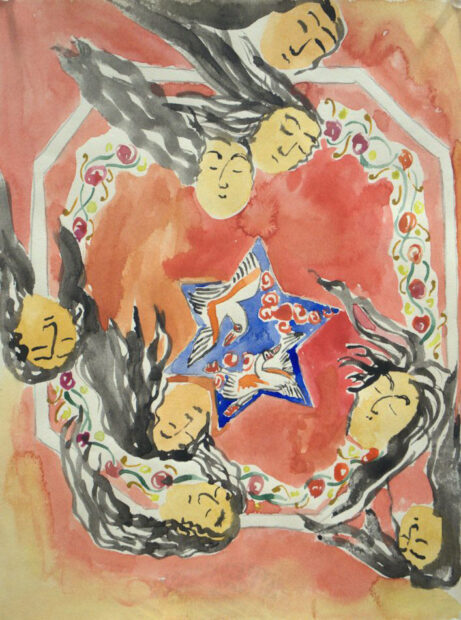

Something else that inspires me is Persian art. Esfahan is a large city with lots of gorgeous historical architecture. For example, the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in my hometown is very beautiful. Legend has it that the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque was built by Shah Abbas I for his wives, so that is why its shapes and curves are so feminine and why it has light blues and light cream colors.

Unlike Western art, Persian art is also very flat, it’s very 2D, and that is why I like to paint people in flat colors. Ancient Islamic art uses patterns of nature and the focus is on God. For example, traditional Western art portraits are realistic, but traditional Persian art does not really use shadows on portraits of people. You will see outlines of people in a lot of my work, and I write in my work in the Persian calligraphy style.

CK: How did your work shift in 2021 from 2D to installation and performance? Was it because of your move to the United States?

AY: The move to the United States was only part of this change. I had to choose a concentration when I applied for my MFA degree, and I chose painting and drawing since I liked to paint with traditional painting materials.

But I was really impacted by protests for women’s rights in Iran in September 2022. Iranian women have been fighting for their rights for many years, and many women took to the streets to try to protest. And it was not just women, but also men.

Being far from home during this was very heartbreaking. I decided that I had to do something, that I had to protest. Female protestors started cutting their hair to show support for Iranian women. So, during one of the performances for my fall 2022 semester review, I cut my hair and gave it to all of my professors. I started crying, and my professors started crying. I couldn’t believe it. It was like my hair turned into something sacred and important. This was the first time I have ever been surprised about my emotions, and I started using my own body in my work.

CK: Your body is now part of much of your work. What are you most interested in investigating with the body and your performance art?

AY: I am interested in answering this question: what is the meaning of being a woman? I want to show the magical side of the women of the non-Western world who are forgotten. I also want to protest and want for my body to be the artwork.

We [humans] are damaging the world and our bodies because we have forgotten about the feminine side of ourselves, which is why I use mirrors in my work. I think mirrors are very feminine, and they let people see themselves when they pass by my work. I want to bridge the gap between the work and the viewer, in order to remind them of their feminine side.

In Home, I made a home for myself out of fabric, painting, and hair. It was a tent that I made for myself because I am so far away from Iran. People could enter the tent and experience this space for themselves.

CK: Are there any specific artworks of yours that stand out to you in the way that you juxtapose mirror/s and hair?

AY: Yes. There is my artwork Rebirth. In the center, I include the imagery of a pomegranate, which is imagery found all over Islamic mosques. When people pass by this artwork, they see some of their reflection too, as I used a sheet material that is reflective. Audiences also see the fabric, which again refers to womanly crafting, and I have included hair, which is all mine.

CK: Can you explain why you asked people to cut their hair in your thesis show?

AY: I cut my own hair at my residency at the Anderson Arts Center in support of women’s rights. And again during my thesis show, I cut my hair and asked people who wanted to participate to cut their hair as well. I glued their hair to mirrors and let the participants write down a sentence about it to document their emotions. I started trading my hair and art with my participants’ hair in order to share my feelings with theirs.

I ended up with hair from fifty people at the end of the show. I was very happy with the turnout, and I did not expect so much hair.

CK: What do you hope that people understand or take away from your work?

AY: I want people to be aware that women — especially in the Middle East — are fighting for their rights. I support them because I am one of them. I am a migrant who still travels back home to Iran and then comes back here to the United States to work. I want to show the world the power of women and encourage them to support us. We need people to see us.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.