For writers and artists, it often feels like there is a lot of importance placed on the individual, on the idea of a singular voice. However, many of us know that neither art nor life happens in a vacuum. We are all influenced and inspired by others, whether they be mentors, colleagues, family, or friends. But even beyond this realm of influence, like many others in my fields, I have dabbled with more direct forms of collaboration in both my art and my writing. From working on joint endeavors like films and photographic projects to co-authoring articles, I revel in the act of working with another person, as it brings new ideas and perspectives, and has the power to generate something bigger and better than what I alone can accomplish.

Last fall, William Sarradet and I had a conversation about AI-generated art, and since that time, the topic has been in the back of my mind. As a person with aphantasia (the inability to visualize thoughts and memories), the use of AI-generated art offers me a chance to bring to fruition a limitless world of possibilities. As a writer, I often think about ChatGPT and the various ways it is being used: by institutions to curate exhibitions, by educators to create tests and quizzes, by social media managers to write engaging captions, by students to write essays, and even by authors to inform their work. Though weary of the sourcing of both visual and written information by AI-platforms, I am a proponent of exploring new technology.

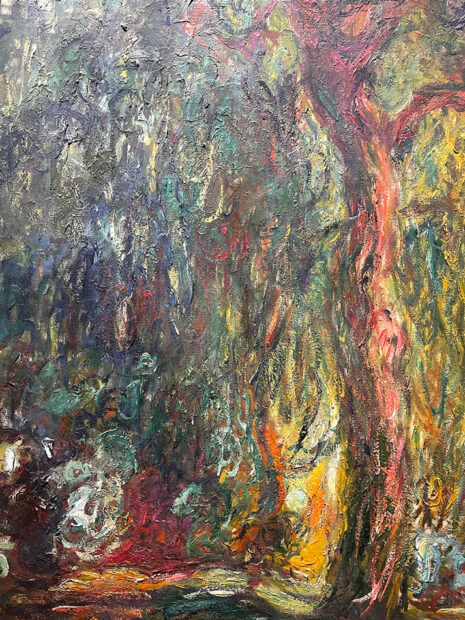

So, it is with some hesitation that I’ve decided to follow my interest in collaborative projects by engaging ChatGPT to assist in writing about a work of art. I’ve chosen Claude Monet’s “Weeping Willow,” one of my favorite works in the Kimbell Art Museum’s permanent collection. Aside from it being a significant later work by the artist, I also selected this piece because I assumed there would be a wealth of information online about Monet’s oeuvre for ChatGPT to pull from in its writing.

I went to revisit the work recently and began writing a reflection on the painting. I entered the first few sentences of my thoughts into ChatGPT and let it finish the paragraph. From there, I accepted parts of what the software offered, wrote and input more, and asked for more. When the software’s writing felt out of place, (if this happened it was oftentimes either too flowery or repetitive), I would point this out and ask for something different. At various times I gave it different directives to see what it would look like for ChatGPT to “expand on” versus “rewrite and elaborate”; I similarly told it to “Keep my original words and add additional descriptions.” I continued this back-and-forth until the writing felt complete. Below, you will find the co-written article, with text offered by ChatGPT in italics to differentiate our voices.

****

Over a decade ago I visited the Kimbell Art Museum with my then-six-year-old daughter, Julia. We saw, learned about, and talked about a lot of art. Though our visit was brief, it left a lasting impression on both of us. The Kimbell Art Museum’s serene ambiance and carefully curated collection provided a rich and immersive experience, fostering an appreciation for the beauty and diversity of artistic expression. One piece that particularly stood out was Claude Monet’s “Weeping Willow,” which provided an opportunity for a conversation we hadn’t broached before.

At the time, we were conducting research for my Master’s thesis on family learning in museums. Our visit to the Kimbell was more than just a casual outing; it was a calculated expedition, with our mission clear: to unearth the secrets of how families learn and bond in these informal learning institutions. We explored an array of self-guided materials, including an audio tour that was available for families. As we walked through the galleries, Julia searched for labels that had a symbol indicating there was an associated tour stop. It was a scavenger hunt in the world of art, a thrilling prospect for a child eager to explore. Each stop shared information and context about the art, and the family stops, as compared to the standard audio stops, were crafted with younger audiences in mind.

As we sat in front of Monet’s “Weeping Willow,” a calm voice on playback posed a series of thought-provoking questions, evoking what it might feel like to be seated under the tree. The questions came too quickly for us to discuss, but sparked each of our imaginations as we looked at the work. Then the voice shared some context about the place depicted in the painting and briefly touched on the deaths that affected Monet’s life at the time, including the loss of his wife and son. The two-minute tour ended by likening the colors present in the artwork — an array of layered brushstrokes ranging from deep indigo to golden yellow — to Monet’s emotions at the time.

I remember trying to navigate Julia’s questions about death. She was just six and had not yet experienced loss in such a significant way, but still empathized with the idea of the painter losing his family members. Though this isn’t a specific memory that has stayed with Julia, likely because it was just one stop of many on the tour (which was one tour of many we did that year for my thesis), each time I revisit Monet’s “Weeping Willow” I can’t help but think about the sadness in my daughter’s voice as we spoke about the work.

Claude Monet, “Weeping Willow,” 1918-19, oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 47 1/4 inches. Kimbell Art Museum collection.

While this history always comes to mind whenever I see the painting, I also try to let myself sit with the art on my own and go beyond that experience. The piece has always drawn me in because, since I was young, I’ve always felt an affinity with trees. As a child I would climb the trees in our yard, and as an adolescent I was always looking to trees as a source of inspiration for my art. They are all around us and we live in a symbiotic relationship with them — we rely on each other as living beings to survive. Trees have also always been a strong metaphor for how I strive to live: forever grounded and forever reaching towards the sky.

This connection that I have with the subject matter, paired with Monet’s ability to captur[e] the ephemeral qualities of light, color, and atmosphere in nature, makes the painting irresistible to me. Monet’s short, broken brushstrokes and vibrant palette bring a simple scene to life with movement and vitality.

On this most recent visit, I stood in front of the painting and considered the cascading leaf-filled branches. I noted how much they reminded me of the playful act of letting my hair fall in front of my face, tumbl[ing] gracefully, creating a whimsical veil to shield myself from the world… I marveled at the intimate connection between the elegant weeping willow and my own longing for seclusion, realizing how the branches, like strands of hair, served as a tender sanctuary, a silent fortress shielding Monet from the outside world, just as my own hair shielded me in moments of contemplative solitude.

Detail of Claude Monet, “Weeping Willow,” 1918-19, oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 47 1/4 inches. Kimbell Art Museum collection.

I had always paid so much attention to the painting’s intricate interplay of colors, the hard divide that the tree trunk creates between cool and warm, between shadow and light, between gloom and hope. But this time I focused much more on the texture of the paint and Monet’s compositional choices. From the audio tour (the same one today as twelve years ago) and the wall label, I knew that at the time of painting this work (and the related series of nine other willows), Monet’s home was mostly empty.

It was 1918, and while the advancing German army grew nearer, the artist was resigned to stay and meet whatever fate greeted him. But standing in front of the painting this day, looking beyond Monet’s color palette and thinking instead of the tree, which fills the canvas from edge to edge and comes out toward the viewer with a rich impasto, provided space for new considerations about the work. Each layer of paint became a tactile echo of the artist’s profound desire to hide and disappear within this fortress he created for himself.

Detail of Claude Monet, “Weeping Willow,” 1918-19, oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 47 1/4 inches. Kimbell Art Museum collection.

****

In truth, I didn’t really know what to expect as I embarked on this collaborative writing project. I knew where I was starting — with a painting that I enjoy and have a specific memory of, but that I admittedly do not return to often. The great thing about collaborating with another artist or writer is often the conversation that emerges in the process. The process of co-authoring articles typically begins with discussing the goal of what we are writing and, together, establishing a structure. From there, we divvy up sections of the article that each of us will take the lead on. After writing separately, we edit each other’s work and meet again to discuss larger ideas and the flow of the article. We push each other, we acknowledge each other’s work, and in doing so we create a unique thing together that at once represents our individual voices and our collective voice.

But how do you collaborate with a machine that does not have its own individual voice, but is rather already an amalgamation of voices and text it has acquired? I came to ChatGPT looking for a partner, but what I found was a tool. Sure, I could (and did) ask the software to create an outline, and I also asked it to write portions of the article (which it did), but while I could provide feedback for it, it was not a balanced collaboration. When I asked it to modify, edit, or expand on something I wrote, it simply rewrote it in “its own voice.” Of course there wasn’t a back and forth; of course there wasn’t a collaborative voice to be had, because unlike individuals, ChatGPT does not have its own perspective to lend. In its words, “As an artificial intelligence, I don’t possess personal opinions or emotions, but I can offer an analysis based on the information available.”

2 comments

Fascinating! I really enjoyed this.

Flaubert, its not!

An automated thesaurus, maybe.

I agree with your assessment of AI being a tool, not a partner/collaborator. And in my experience to date, AI and machine learning are ironic oxymorons.

As time changes the world, I do see imagination thriving in a personal world isolated by electronics (ex: video gaming) and devoid of social touch and visual gazes. I do not prefer this world.

Maybe I am looking ahead to the good old days (I hope not) but I believe the last refuge of reality is the domain of the artist; art is the “least lie”, and I hope an artist stays true to themselves and the intimacy of their imagination, not to (use) a machine intelligence or literal tool. (Well, that dream is long gone as you could consider a computer or typewriter or brush a tool).

But then I believe in living in/with happiness too!

Nice article.