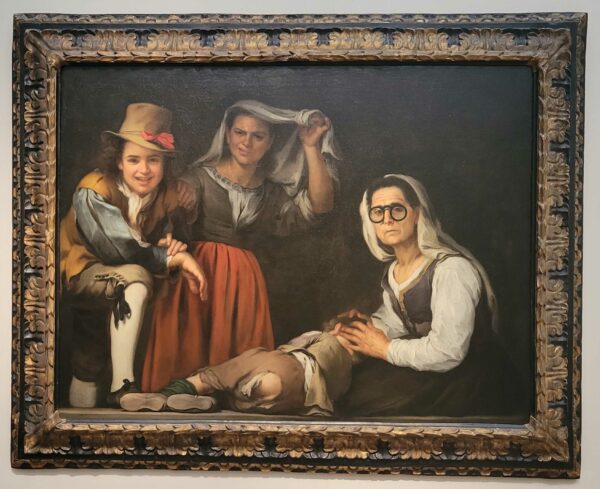

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo “Four Figures on a Step,” c. 1658-60, oil on canvas. Image courtesy Kimbell Art Museum Fort Worth.

I am an art person. I love visiting art museums and galleries in order to immerse myself in the beauty and history of the works on view. I recognize that I am a rare breed. I have many friends that do not find the same allure. To them, much of what they see at museums is old and, worst of all, irrelevant. Therefore, I love to highlight exhibitions that are novel, innovative, or responsive to the moment we are living in. Murillo: From Heaven to Earth may not fit that criteria at first glance, since it is a beautiful exhibition of genre and portrait paintings by seventeenth century Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. The centuries that separate current viewers from the works can serve as a barrier to deep connection and appreciation, but learning more about the context in which Murillo worked and the issues he addressed can serve to bridge that gap.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, “Two Women at a Window,” c. 1655-60, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Widener Collection, 1942.9.46.

One of the elements of Murillo’s style that’s so captivating is his invitation to viewers to participate in the scene. Two Women at a Window is a prime example. In this painting, a young woman longingly stares out a window, towards the viewer, as an older woman stands behind the shutter, covering her own grin with a rag. We are invited to speculate on why the woman is laughing, and it is tempting to crack a smirk at the fun of this work before gliding on past this window to the next painting. However, this is where I argue for slowing down and taking a closer look in order to understand how viewers of the artist’s day would have appreciated these works.

Murillo’s contemporaries would have understood this scene as a commentary on modesty and virtue. This young woman is opening herself to the world, marking her transition into womanhood. However, it is left to the viewer to wonder what path she will choose in a society filled with contradiction. Seville, Spain was a devoutly Catholic town, yet vices like prostitution (subtly suggested by the woman’s presence at a window) were ever-present. This is where an exhibition of Murillo’s secular works is most intriguing. He does not shy away from depicting the real life challenges facing everyday people in Seville. As in the present day, young women faced immense pressure to fit into molds of “good” and “virtuous” womanhood. However, these women had limited control over their financial futures, especially if they were from the lower classes. As Murillo would have wanted his viewers to consider this young woman’s choice, I also think viewers today should pause to consider the forces that would have shaped her choices. How did she see her future prospects? It is in this attempt at perspective-taking that we might find a little of ourselves in the exhibition.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, “Old Woman with a Hen,” c. 1645, oil on canvas, Bayerishe Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. 608.

A great starting point is Old Woman with a Hen, a work in the first gallery of the show. This oil on canvas painting focuses on an elderly woman with a gaunt face and missing teeth who is standing in a tattered shirt. She faces the viewer, presenting a hen that’s clearly prized for the many eggs filling the basket on the woman’s arm. To the hurried visitor, this painting is an attempt to solicit sympathy for a poor, elderly woman. However, Murillo’s works are filled with symbols that would have been easily read by his contemporary viewers, but may be less subtle to us in the present day. In this particular case, the hen is a symbol of fertility and motherhood. Yet, we see a woman who stands alone in rags, with no one to care for other than her hen. She did not become a mother, and now suffers the consequences in her old age. Murillo intended this work less as a call for sympathy, and more as a cautionary tale.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, “The Toilette,” c. 1655-60, oil on canvas, Bayerishe Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. 489

As a counterpoint, we find The Toilette. In this domestic scene, Murillo depicts an older woman tending to a young boy who rests his head on her lap as he enjoys bread and plays with a dog. She leans over him, removing the lice from his hair. While this family is by no means wealthy, we can see they have a comfortable home with their basic needs met. In devoutly Catholic Seville, this woman is representative of “good” Christian womanhood, caretaking for children. She is also representative of the “good poor,” an ideal that is explored further in the exhibition. This painting lets me lean into it personally, letting me find areas of resonance with life today: How are women today still subjected to societal pressures and judgment over their choices regarding motherhood? What are the expectations of women to care for others? How are women who choose other life paths, that do not include rearing children, set up for judgment or ridicule?

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, “Invitation to a Game of Argolla,” c. 1655-70, oil on canvas, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London. Bourgeois Bequest, 1811, DPG224

Returning to ideals of morality around poverty, several of Murillo’s genre scenes regard poverty and temptation, like Invitation to a Game of Argolla. In this painting, a young boy sprawls across the foreground in a reclined position with bare feet and a bare shoulder as he plays argolla, a game similar to croquet. A basket rests on the ground behind him, indicating he is an errand boy who has stopped his task to focus on recreation. What is most striking is the mischievous smirk on his face as he looks up at another young errand boy carrying a jug and loaf of bread. This boy knows he has work to do, but is confronted with the temptation to play instead. A dog, standing at his side, awaits his decision along with us viewers, eager to snatch the boy’s bread if he pursues this distraction instead of making the “good” choice to continue with his work.

Installation view of “Murillo: From Heaven to Earth,” on view at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth.

Murillo is setting up a contrast here, and invoking some harmful stereotypes about poverty. We see a dichotomy between the “good poor” and “bad poor.” For Murillo and his contemporary audience, the “good poor” are those who work hard, maintain a nurturing home, and seek to better themselves despite the station they were born into. The “bad poor,” on the other hand, are lazy and susceptible to temptation without regard to improving themselves in a Christian fashion. It is important to keep in mind Murillo’s intended audience; in seventeenth century Seville, an artist created commissions for the Catholic church, wealthy aristocrats, and merchants. It served their purposes to look at poverty as reflective of personal morality rather than societal failings.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, “Portrait of Don Antonio Hurtado de Salcedo y Mendoza, Marquis of Legarda,” c. 1664, oil on canvas, Colomer collection, Madrid.

Viewers are treated to a glimpse of the successful men that comprised Murillo’s audience of patrons in the portraiture section of the exhibition. In Portrait of Don Antonio Hurtado de Salcedo y Mendoza, Marquis of Legarda, Don Antonio looms large in front of a beautiful landscape with a rifle steadied in his fist. At his right, a servant hunches down with hunting dogs over the haul of partridges Don Antonio successfully hunted. Here, Don Antonio truly is master of all he surveys: his lands, his servants, and the animals, domestic and wild. If Murillo’s genre scenes show “good” and “bad” poverty, his portraits show “good” aristocracy. There is also a strong element of paternalism in this work. This man embodies strength, vigor, and most importantly, control. He is fully in control of himself, and can thus attempt to control those in his service, making them choose a more virtuous path. Murillo’s contemporaries would have received the message that this servant is not off facing temptation, but is actively working hard for the betterment of Don Antonio and himself.

Admittedly, these ideals continue in the present day and in the United States. There are many harmful narratives that persist as a result of the long-lived misconception that this nation is a pure meritocracy, meaning that if one works hard enough they can achieve the American dream. There are ongoing, divisive debates about the role of structural and systemic inequality on poverty, as it is far easier to cast aside the problems of others by blaming their lack of personal responsibility. There is often an insistence to focus support on those in power (tax cuts for companies and the wealthy to stimulate trickle-down economics), rather than extending direct aid to those truly in need. Thus, I look at the works in this exhibition not as the moralizing tales that Murillo intended, but an indictment on society for how we frame poverty historically and presently to avoid truly confronting the structures that perpetuate higher rates of poverty for large groups of peoples.

Unknown artist, “View of the Alameda de Hercules,” c. 1650, oil on canvas, Abelló Collection, Madrid.

This exhibition provides viewers a wonderful opportunity to briefly enter Murillo’s community and seventeenth-century Seville. There is diversity, inequity, conflict, but there is also hope. With the right choices, a better future can be had. The question handed down to us is what choices we will make. We have the benefit of looking to artworks like these and the past they represent to decide if we continue the course, or radically reframe our views. In any case, I think all can benefit from taking a moment to sit before exhibitions like these to ponder our own relationships to the ideas captured.

Murillo: From Heaven to Earth is on view at Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth through January 29, 2023.

2 comments

The highly dubious definition of the word “harmful” implied by its usage in this review is neither legitimate, valid, appropriate, nor insightful.

Ultimately, when present-day progressives attempt the impossible task of fitting all of human history into the Procrustean bed of their extremely limited and narrow-minded worldview, the result is a loss of understanding, rather than a gain of the same.

[Edited of epithets for publication approval ✌️]

This review seems hampered by a politicized prejudice. The reviewer’s simplistic and anachronistic ideology is clouding her ability to see Murillo’s explicit support and empathy for the poor and marginalized. His genre pieces are critiques of the economic inequity of his society. Murillo was raised in poverty and disadvantage. It’s unfortunate that a political slant misses the profound nature of Murillo’s genre work. Ideology—when applied to art—means the death of intelligence. As soon as one believes a doctrine of any sort, or assumes certitude, one stops thinking about that aspect of existence.

And a hearty ditto to the comment my Laurence Allan Elder.