This is the second in a series of interviews talking with the collaborative team leading artist Vicki Meek’s Urban Historical Reclamation and Recognition project in Dallas’ Tenth Street Historic District Freedman’s Town neighborhood in Oak Cliff. The project is sponsored by the Nasher Sculpture Center.

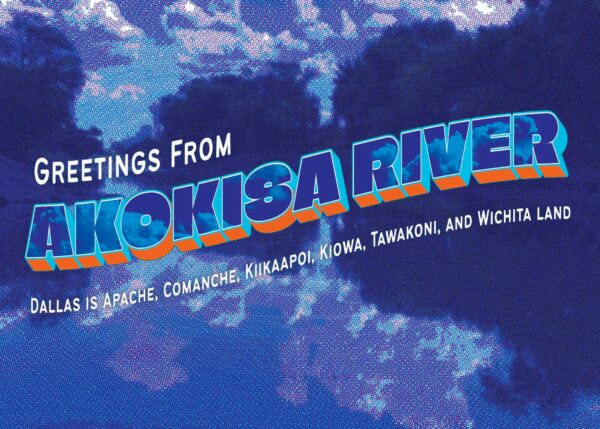

Angel Faz, “Updated Postcard from the future with updated spelling of Akokisa,” 2023, with Teatro Dallas.

I reached out to Angel Faz a few months ago to discuss their creative practice and the threads in their work that connect water, land, resilience, care and object-making. We discussed projects of the past, projects of the future, and whether or not it’s our responsibility as artists and people of color to provide care.

Carris Adams (CA): One of my first questions is, where are you currently? You were in Santa Fe for a residency last I checked.

Angel Faz (AF): Yes, I am Dallas-based. I’ve lived in Oak Cliff for 11 years. And now I am traveling back and forth to New Mexico and planting new seeds around creative environmental change. It is a hot topic right now because it’s undeniable.

CA: What did you explore while at the residency?

AF: It was great. It was a much slower pace and I challenged myself to think of how to make work that requires less materials. I thought about making work that is more time and land-based versus materials-based.

I made paper out of cottonwood and sage. I wrote a lot more there. I made ink. It strengthened my practice to unlearn some things.

CA: Did you discover a new method of working that you will carry-on employing?

AF: Yes, probably making less work and instead making more intentional pieces. It’s a fine line to walk as you work with institutions, galleries, or collectors that acquire physical work, and balancing the work/life balance. I think I know the difference now between moving an idea forward and what is tangible for that part of the art world that needs an artifact.

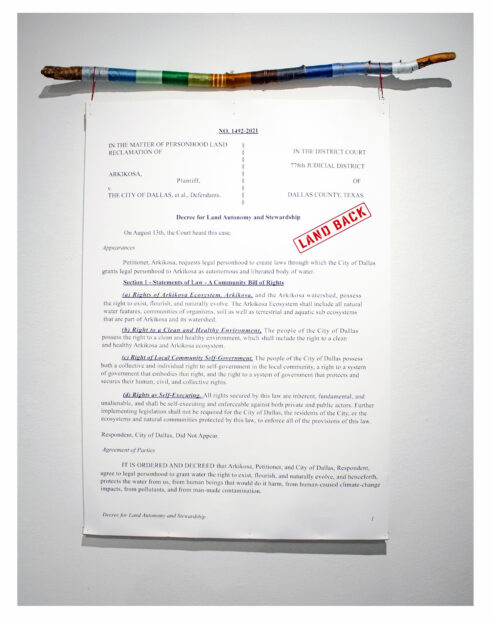

Angel Faz, “Arkikosa Project,” 2021, Arkikosa sues the City of Dallas, print, found wood, embroidery thread, 32 x 65 inches.

CA: Is that scary?

AF: Sometimes it is scary. Maybe I make a living in a different way, which is how I have approached making a living and has given me more freedom. It’s a fine line.

CA: Absolutely. Largely the art world thrives on objects. Even if it’s performance-based, the market still wants it to be replicated or have some proof of its existence. This, coupled with water as a medium, is interesting to me because it’s not always something you can control. Globally there are shortages and everybody needs it. Can you speak to how your work uses water as its subject matter and medium?

AF: I like to take people on a journey when making work, and especially when using the medium of water. The primary goal is to help people connect, one-on-one, with water. We take it for granted that you can turn on a faucet and water comes out. Texas still has a lot of aquifers that we depend on, but the rivers and aquifers have been reduced. There are water conferences in New Mexico, but we need them in Texas, too, to begin considering it as a finite source. For instance, what if every house had a way to collect water? This then brings into question how we can build homes to support this structure. I’ve been researching adobe building — creating something from water and dirt. The next route for me is to partner with a scientist. Artists need seats at the table for these water conferences versus it just being a bunch of city guys. I think if you see the problem, it’s up to you to figure it out.

CA: It sounds like you have a couple of new projects! A “Water for the People” conference perhaps, one that is inclusive of artists and creative people with installations and activations… get started!

To take it back, I know that you grew up near a superfund site and that your family often told you stories of how they experienced The Trinity River over forty years ago. Can you speak to how and when you became interested in this work that utilizes land, place, space, and water as subject matter and media for your practice?

AF: There is a project called, De-Colonize Dallas from 2017. It was during this project that I began to think about what it looks like to decolonize this land, so-called Dallas. I began examining my family history from when they moved here from South Texas. My family is indigenous and was here before this was even Texas.

I was raised mostly by my mom, and I started asking her about becoming settlers in Dallas. The stories began with her talking about the Trinity River. They would go trapping and hunting for food near the river. My mother grew up in the same neighborhood since the 1950s; she still lives there. And when I began digging into these histories I started to ask myself: why have I never been to the river, what is my part of (de)colonization, and how can we heal how we have scarred the river through misuse? Part of healing is visiting, establishing connections, and decolonizing within myself.

CA: Part of that healing is also changing the idea that “it serves you” versus us and the land servicing each other. Another way of healing is perhaps changing the name of the Trinity River. Can you speak to your Akokisa project? Will the City of Dallas actually change the name of the river?

AF: A few things happened all around the same time. Teatro Dallas asked me to participate in their Monuments of the Future project. The prompt being: if I were to make a future monument, what would it be? I began doing research around this project because I knew it was going to be about the Trinity River. I worked with Jerry Hawkins of the North Texas Racial Transformation and Healing Center, and Brian Larney, President of American Indian Heritage Day, who was a part of the cohort in 2019. During this research period, Hawkins provided the research that prompted Peter Simek to write an article about the river’s original name. We continued working on the monument project from our particular perspectives until we could reconvene.

We thought that Akokisa was a Caddo word, but it turns out that it is an Atikapan word. We’re playing a game of telephone with history and what we think we know is based on someone else’s hearsay.

Akokisa gained a lot of steam in 2021 and 2022. It became a city proclamation from Omar Narvaez of District 6, which recognized the name of the river as as Arkikosa. But we may have to adapt again. I stand by the project because we were dispelling settler colonial myths and honoring the indigenous people. I worked with Alaina Tahlate of the Caddo nation to acknowledge the history and the culture because we are still here and thriving

CA: Right. So much of the history that we’ve learned is really written by the conqueror. How do you manage or negotiate the politics within public projects that involve the city, community, and your own desires for the work?

AF: When we found out about the city proclamation and report in 2022, it showed that the artist campaign worked! However, now that we know of the language slippages it may have to change again. I’m not sure the city will move forward with the project, but it was nice to have the city understand the cause. You have to remember that working with the city, and the community can have varying outcomes.

CA: Yes. It doesn’t shock me that it’s a constant negotiation, which sums up “government” in a nutshell.

Your practice has many threads, one of which is the object (sometimes ephemeral), and the other, which is social. The social has an emphasis on creating experiences for reflection, healing, and care. It feels like artists of color largely take on this role. And historically, in communities of color, because of disenfranchisement, we have to make a way for the things we need. Is it our responsibility not only as artists but people of color to steer the care and healing of the world? Or does it matter, as it’s everyone’s responsibility?

AF: That’s a thoughtful question because water concerns us all. While it’s not exclusively a POC responsibility, I find great purpose in contributing to this cause, which helps me sleep better at night. I see a growing interest among artists and institutions in addressing water-related issues, and I say, “Go for it.” Water is hiring!

CA: Water will always be hiring because nothing can exist without water. Do you see yourself branching outside of water to include the other elements?

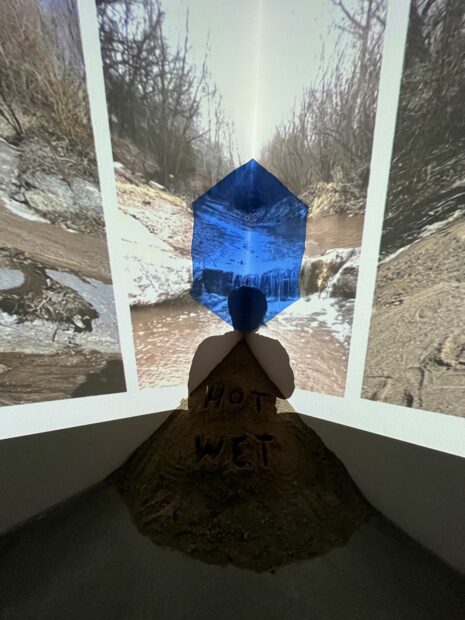

AF: Yes! I’m now exploring earth, specifically adobe. I’ve gone to New Mexico to attend adobe heritage workshops with Joanna Keane Lopez and Ronald Rael, where I learned how to mix the appropriate ratios of earth materials to create adobe. The more I dig into one element, the more I find out about another and how they are all connected. New Mexico is both the past and the future. They are having conversations about the future, but are also using practices of the past that we have largely moved away from.

Angel Faz, “Listening to Water,” 2023, performance, projected triptych, sand from Santa Fe River, variable-sizes

CA: That’s the great thing about art. The network of your interests shrinks and grows forever. It’s not something, I believe, that you can know enough about. Can you speak to the connective threads of water, place, and care between your work and the Urban Historical Reclamation and Recognition project with the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas?

AF: We are in the research phase of the project. I’ve found some really interesting things. For instance, the 10th Street District was a self-sustaining place. The people who lived there grew their own fruit and nut trees. They were subjected to a lot of flooding as well, but it was essentially its own city. The first Black funeral home and dry cleaner of Dallas was there, along with other small businesses. They had food and culture there. We are speaking to residents and recording them and their stories. They had 70 years of self-sustaining economy, until the highway was built and cut them off from their other communities.

Angel Faz, “Decolonize Dallas,” 2023, Texas Gulf Coast Toad, relief print at Trammel Crow Park’s receding lake bed, 24 x 18 inches

CA: I read something about you that said “your work inspires others to imagine a world where justice prevails.” What does that world look like for you?

AF: For me, it goes back to self-sustaining village models of developing our own communities and exchanges. The future of justice means that we return to self-sustaining models. We look out for each other. Justice prevails would be the city helping 10th Street District restore these homes, versus moving them out by raising taxes or isolating them. We have nine historical homes in the 10th Street District, from shotgun houses, craftsmans, bungalows, and more. The City of Dallas has chosen not to restore these homes because, more than anything, they want to develop the land. Justice prevailing would be the opposite of that.